Jonas Short Mound under excavation.

The man on the right is standing at about the original

ground surface. Most of the mound seems to have been

built in a single construction episode. TARL archives.

|

Perforated elk teeth (preserved by

proximity to copper artifacts) and quartz crystals from

Jonas Short. Five of the crystals were shaped and perforated

or grooved to serve as pendants. TARL archives.

|

These large dart points and knives

from the Jonas Short Mound were obviously made by a

master knapper and used as ritual items. The flake scars

(chipping marks) on the extraordinary yellow point have

been completely obliterated by polishing, underscoring

its symbolic value. TARL archives.

|

Large dart points knives as they

were found within the Jonas Short Mound. TARL archives.

|

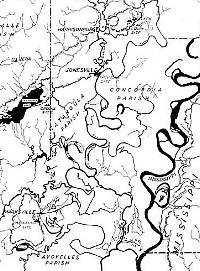

The approximate limits of the Woodland

culture areas defined within the main Caddo Homeland

and some of the better known Woodland sites dating between

about 500 B.C. and A.D. 800. Graphic by Dee Ann Story.

|

Test excavations underway in 1963

at the Late Woodland Pace site on the Louisiana side

of Sabine River just above Toledo Bend Reservoir. TARL

archives.

|

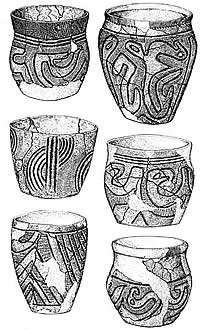

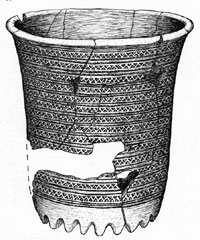

The hallmark of Fourche Maline culture is a well-developed

ceramic tradition known for its plain and minimally

decorated flat-bottomed vessels shaped like flower pots.

|

Late Woodland pottery vessels from

the Fanny Snipes site on the Sulphur River near Texarkana.

The jar on the left resembles French-Fork Incised, a

Coles Creek type, but was probably made locally. On

the right is a typical "flowerpot" Williams

Plain flat-bottomed jar, one of the hallmarks of Fourche

Maline culture. TARL archives.

|

Typical Fourche Maline Williams Plain

jar from the Crenshaw site, Miller County, Arkansas.

Photo by Frank Schambach.

|

| The hallmark of Mossy

Grove culture, its sandy paste ceramic tradition, was

probably introduced or inspired by the Tchefuncte culture

in the lower Mississippi Valley. |

Flared-rim Williams Plain jar from

Fourche Maline contexts at the Crenshaw site, Miller

County, Arkansas. Photo by Frank Schambach.

|

The Mill Creek culture encompasses the period from

about 200 B.C. to A.D. 800 and is contemporaneous with

Fourche Maline and Mossy Grove, but different from either.

|

Double-bitted stone axes are often

found in Fourche Maline sites. These examples are from

Red River County, Texas. TARL archives.

|

|

Only a few of the burials at Coral Snake Mound

were definitely accompanied by grave goods, but small numbers

of exotic artifacts were placed into the mound as caches or

discrete clusters. Some artifact caches and other isolated

artifacts may actually represent burials in which the bones

did not survive. Regardless, these artifacts clearly represent

purposeful deposits of offerings honoring the dead. Among

the unusual artifacts are rolled copper beads, copper gorgets,

perforated raccoon teeth, two Marksville pottery vessels, two boatstones

(ground and polished artifacts shaped like a boat), and a

unique quartz figurine. The captions of the accompanying photographs

provide further details.

Three radiocarbon dates and the associated Marksville

pottery vessels indicate that Coral Snake Mound was in use during Middle

Woodland times in the early centuries A.D. Some effort was

made to locate contemporary habitation areas that might have

been associated with the mound/cemetery, but none were found.

Scattered artifacts found in and near the mound such as pottery

sherds, flint flakes, and broken dart points, probably represent

occupational debris, but the mound site itself appears to

be mainly a cemetery. The precise cultural affiliation of

Coral Snake is debated. While it could represent an as-yet

poorly known local Woodland group, Arkansas archeologist Frank

Schambach argues that Coral Snake Mound is part of Fourche

Maline culture.

Another somewhat similar site is the Jonas

Short Mound located on the Angelina River under what is

today Sam Rayburn Reservoir, some 40 miles (70 kilometers)

west of Coral Snake. The Jonas Short Mound was 29 meters (94

feet) in diameter and 2.4 meters high (almost 8 feet) and

was built over the cremated remains of at least two individuals

placed into a shallow pit. Charcoal and scorched earth suggest

that the cremation took place within the pit, followed soon

by the building of the mound, probably in two stages. The

cremated remains were accompanied by two copper bracelets.

Five artifact caches were found in the mound fill that may

have accompanied burials (if so, the bones decayed completely)

or may be offerings honoring the cremated individuals. Among

the unusual artifacts in these caches are boatstones, perforated

elk teeth, a copper reel-shaped gorget, large chipped stone

knives (bifaces), an extraordinary polished dart point, and

11 quartz crystals, five of which were shaped and perforated

or grooved to serve as pendants.

The date of Jonas Short Mound is uncertain,

but it probably also dates to the Middle Woodland period as well

and may be a bit earlier than Coral Snake judging by the reel-shaped

copper gorget. Similar artifacts are known from early Marksville

burial mounds and in burial mounds of the Adena culture of

the Ohio River valley far to the northeast. The presence of

plain sandy paste pottery and the absence of Marksville

pottery or bone- or grog-tempered pottery suggests that Jonas

Short was created by a different culture than that of Coral

Snake (or possibly by the same culture in earlier days). It

falls within the area where the Mossy Grove culture existed,

as discussed in Part 2. Schambach thinks Jonas Short is also

part of the Fourche Maline tradition.

Other Middle Woodland sites with burial mounds

occur in the vicinity of the Great Bend of the Red River in

northwest Louisiana and southwest Arkansas. In fact, there

are probably as many Middle Woodland mound sites in the eastern

part of the Caddo Homeland as there are in the LMV, although

few are well known. The Bellevue Mound and related sites in

northwest Louisiana were thought by earlier researchers to

represent a phase of the Marksville culture. Such LMV-centric

views are no longer widely held today, as archeologists in

the region see much evidence of local developments that parallel

those of the lower Mississippi Valley. Arkansas archeologist

Frank Schambach sees these sites as early expressions of Fourche

Maline culture (see Part 2).

In Arkansas, Shane's Mound and Red Hill Mound

are examples of burial mounds with similar grave offerings

to those found at Coral Snake including a Marksville stamped

bowl containing copper beads (Red Hill). Both mounds are associated

with nearby habitation areas (middens) and both are attributed

to Fourche Maline. Interestingly, both the Bellevue Mound

and the Cicero Young Mound (in Arkansas) were built over the

remains of structures, a practice which is common at Caddo

sites. These may be early examples of mounds that mark civic

and ritual centers. This is hard to demonstrate because what

little work has been done at most of these sites has focused

only on the mounds themselves.

The succeeding Late Woodland era in the

lower Mississippi valley is divided into two periods, Baytown

(about A.D. 500 to 750) and Coles Creek (about A.D.

750 to 1000), and is a time of great change. Compared to Marksville,

there are more sites, much more ceramic variability, more

densely concentrated populations, and fewer graves with exotic

offerings. Three new developments during the Late Woodland

in the LMV are particularly important: the gradual adoption

and increasing importance of agriculture, the replacement

of the atlatl and dart with the bow and arrow around A.D.

700, and the construction of planned villages and civic/ritual

centers ("mound centers") with flat-topped structural

"platform" mounds arranged around an open plaza.

These complex and interlinked changes coincide with (and are

no doubt related to) comparable developments in many parts

of the Midwest and Southeast including the Caddo Homeland.

We would argue that by about A.D. 800, developments

in the LMV no longer overshadow and anticipate those in the

Caddo area. Said differently, Caddo culture emerges as a distinct

pattern during the Late Woodland period.

Part 2: Woodland Cultures in and near the

Caddo Homeland

The above map shows the approximate location

of some of the major archeological cultures dating to the

Woodland period between about 500 B.C. and A.D. 700. As we

have seen, there was a succession of Woodland cultures within

the LMV spanning this 1200-year era. Unfortunately, the chronology

of Woodland developments in the Caddo area is poorly known

except by general comparison to the LMV sequence. Somewhat

clearer is the geographical distribution of some of the major

Woodland cultural patterns in and near the Caddo Homeland

as shown in the accompanying map. Before discussing the three

Woodland cultures whose boundaries partially overlap with

the area that would soon become the main Caddo Homeland, brief

mention will be made of three related patterns, two comparatively

well known and the other newly proposed and a matter of debate.

The influence of Middle to Late Woodland

cultures of the LMV seems to have extended well up the Red

River into the southeastern part of what would become the

Caddo Homeland. Based on data from excavations at the Fredericks,

Black Lake Bayou, and Lemoine sites (among others) in the

vicinity of Natchitoches, Louisiana, archeologist Pete Gregory

has defined the Fredericks phase (about A.D. 400-700) and

succeeding Lemoine phase (A.D. 700-900). Sites of both phases

are dominated by what appear to be locally made LMV pottery

types. By A.D. 1000, Early Caddo sites dominate the area,

but it is not clear whether this represents the movement of

people or the spread of the Caddo cultural tradition into

the Natchitoches area.

The Late Woodland Plum Bayou culture existed

in the alluvial lowlands along the lower Arkansas and White

rivers and the adjacent Mississippi Valley in eastern Arkansas

between A.D. 700-1000. The best-known Plum Bayou site is Toltec

Mounds, a major civic/ritual mound center containing 18 earthen

mounds enclosed by a C-shaped pattern of earthen berms and

ditches. Ten of the mounds at Toltec are arranged around a

rectangular plaza centered on the largest mound, which is

about 15 meters (50 feet) high. Plum Bayou culture developed

out of Baytown and is considered by many to be the northern

part of the LMV Late Woodland pattern. Interaction with Fourche

Maline and early Caddo peoples to the west and southwest is

indicated by similarities in pottery and by imported lithic

(stone) materials from the Ouachita Mountains in southwest

Arkansas.

Schambach proposed the name "Mulberry

River" to characterize the Woodland culture that inhabited

the valleys of the middle Arkansas River and its tributaries

to the north of the Ouachita Mountains in eastern Oklahoma

and northwestern Arkansas. Mulberry River culture is said

to be ancestral to the Arkansas Basin ("Northern Caddoan")

culture that developed in the same area after A.D. 900 and

created the spectacular Spiro site. While some Oklahoma archeologists

apparently consider the area part of the Fourche Maline Woodland

culture, Schambach sees Mulberry River as being distinct from

Fourche Maline. He points to differences in artifacts, settlement

patterns, and adaptation that set the two cultures apart.

The most compelling line of evidence comes from a study of

dental patterns that suggests the peoples living in the Arkansas

Valley were genetically distinct from those living in the

main Caddo Homeland from Woodland times forward.

Be this as it may, Oklahoma archeologist Don

Wyckoff sees no archeological basis for considering local

Woodland sites to be anything other than Fourche Maline. As

discussed below, the name and the original definition of Fourche

Maline culture is based on work done along tributaries

of the Arkansas River in eastern Oklahoma. Published statements

by various Oklahoma archeologists including Jerry Galm, Robert

Bell, and Wyckoff state that Fourche Maline sites are only

found in the valleys of the northern Ouachita Mountains, while

the Arkansas Valley, proper, was unoccupied until after A.D.

700.

Suffice it to say that the Mulberry River culture

concept is still in its infancy and may not survive. Proposed

archeological concepts are often like that—some stick

and some sink. Happily, here we are far more concerned with

the Woodland cultures of the main Caddo Homeland south of

the Arkansas River Valley.

Fourche Maline Culture

The most distinctive Woodland cultural pattern

in the main Caddo Homeland is the long-lived Fourche Maline

(pronounced foosh-ma-lean) culture tradition. It is named

after a creek in the Wister Valley of southeastern Oklahoma

where the "type" sites (those first used to define

the pattern) were excavated by WPA teams in the late 1930s.

These sites had distinctive thick, dark middens called "black

mounds" that contained a mix of Archaic, Woodland, and

Northern Caddoan artifacts as well as burials.

Beginning in the 1970s, the Fourche Maline concept

has been expanded and redefined by Frank Schambach to characterize

the Woodland cultures in southeastern Oklahoma, southwestern

Arkansas and adjacent areas of Louisiana and Texas. Beginning

dates are uncertain, but the earliest Fourche Maline sites

probably date to Early Woodland times, before 500 B.C., while

the latest date to A.D. 800 (or later), a span of at least

13 centuries. Schambach has divided the Fourche Maline time

span into seven numbered periods that correspond to the LMV

sequence. He has also defined six Fourche Maline phases covering

different subareas and spans of time. Because the dating for

these phases (and the periods, too) is based mainly on cross-dating

with LMV ceramics, other archeologists, such as Story and

Perttula, regard them as highly conjectural.

Outside the Wister Valley, the best archeological

evidence of Fourche Maline culture comes from the Red River

and Ouachita River drainages in southwestern Arkansas where

some 700 related sites have been recorded. Southwestern Arkansas

and adjacent areas of Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Texas appear

to have been the core area of Fourche Maline culture where

some of the oldest, largest, and most intensively occupied

sites are found. Fourche Maline sites are known for their

thick, black middens resulting from habitation and trash accumulation

over lengthy periods of time. It is assumed that villages

once stood in these places, although little direct evidence

of dwellings have been found, probably because Fourche Maline

houses were not very substantial. While most sites are relatively

small, larger villages covering 2 hectares (about 5 acres)

also occur.

The hallmark of Fourche Maline culture is a

well-developed ceramic tradition known for its plain and minimally

decorated flat-bottomed vessels. The most common form is a

jar shaped like a flower pot. Fourche Maline ceramics typically

have thick walls and are tempered with a variety of materials

including grog, bone, grit, and sand. The most common type

is Williams Plain followed by Cooper Boneware and Ouachita

Plain. Excavations of Fourche Maline middens often yield thousands

of pottery sherds. Trade pieces of Marksville and Coles Creek

pottery are known, but more common are locally made imitations

of LMV pottery. Other characteristic artifact types include

Gary dart points and, after about A.D. 500, expanding stem

arrow points, as well as boatstones, double-bitted "axes"

(possibly gardening hoes), clay platform pipes, and seed grinding

and nutting stones.

The economy of Fourche Maline peoples is still

something of a mystery. They obviously continued the Archaic

hunting and gathering tradition and lived in part off of deer,

turkey, and hickory nuts as well as many other wild plants

and animals. The mysterious part is the extent to which they

were gardeners. It seems likely that, through time, Fourche

Maline peoples began growing various native crops including

the starchy and oily plants that were domesticated first in

the American Midwest as well as squash and bottle gourds.

While little direct evidence of gardening so far has been

recovered from Fourche Maline sites, this is probably due

mainly to the recovery techniques used by archaeologists. (Small charred seeds are

only preserved in favorable conditions and can only be recovered

by using a specialized soil processing method called flotation.)

Indirect evidence of horticulture includes the presence of

double-bitted "axes" (possible garden-hoe blades),

the dense refuse accumulations (black middens) at many Fourche

Maline sites, and the increasing evidence that neighboring

Woodland groups living east, north, and west of the area were

part-time gardeners.

Fourche Maline burial practices are generally

similar to Woodland patterns in the Midwest (Adena-Hopewell).

In the Red River valley of southwestern Arkansas, the earliest

burial mounds (ca. 200-100 B.C.) were built on bluff tops

away from habitation areas. These small domed mounds were

built over crematoria (places where cremations took place),

a common Early and Middle Woodland pattern in the Eastern

Woodlands. Some cremated remains and grave offerings are found

within the mounds, but cremation cemeteries such as the Johnny

Ford site suggest that bodies were burned in one place and

interred in another. Somewhat later mounds such as Shane's

mound covered central pits containing cremated remains but

also have small offering deposits (caches) of exotic Hopewell-related

artifacts similar to those found at Jonas Short Mound, 150

miles to the southwest. (While Schambach considers Jonas Short

to be a Fourche Maline site, Story considers the pottery found

there to be that of Mossy Grove culture.)

Between A.D. 100-300, burial mounds such as

those at Red Hill and McKinney in the Red River valley were

no longer built over crematoria. Instead they have secondary

deposits of cremations (McKinney) that are associated with

exotic Hopewell-related artifacts, and Marksville Stamped

bowls. Although neither of these mounds is well known, Schambach

believes they are similar to Coral Snake Mound, which he also

considers to be a Fourche Maline site. The latest Fourche

Maline burial mounds are Mounds C and D at the Crenshaw site

and are thought to date to A.D. 600-700. These mounds were

built in stages and have deposits of skulls and mandibles

with pottery vessels and other offerings that were placed

on the surfaces of the mound stages and then covered by thin

clay caps.

Schambach argues that Fourche Maline culture

represents the mother culture from which the Caddo cultural

tradition develops and sees Fourche Maline peoples as the

direct ancestors of later Caddo peoples. There is much evidence

to support this view. The most obvious is the fact that the

core area of Fourche Maline closely coincides with the core

area of the Caddo Homeland coupled with the absence of a gap

in time between the two cultural traditions. There are seemingly

abrupt changes in behavior including new burial patterns,

ceramic styles, increased mound building, increasing use of

mounds as building platforms, ritual destruction and capping

of public buildings, and the introduction of maize agriculture.

Nonetheless, these appear to represent local social and economic

developments rather than the movement of a new people into

the area. While these changes may seem abrupt, the cultural

transformation from Fourche Maline to Early Caddo probably

transpired over several hundred years (ca. A.D. 700-900) and

it may well be more complicated than implied by the mother

culture idea. There are two other Woodland cultures in east Texas that probably

contributed to the development of the Caddo cultural tradition,

Mossy Grove and Mill Creek.

Mossy Grove Culture

The Woodland period archeological pattern in

southeast Texas along the upper Gulf coast and inland into

the southern part of the Piney Woods looks quite different

from Fourche Maline. Many of the differences obviously relate

to the contrasting environments. Southeast Texas has greater

rainfall, higher humidity, a longer growing season, more swamps,

less oak-hickory forest, and, of course, the estuaries, bays,

and barrier islands along the Gulf Coast. These environmental

differences resulted in dissimilar economic patterns, access

to raw materials (scarcity of stone, for instance), shelter

needs, and so on. The area is also less conducive to farming.

Farther inland toward what would become the southern boundary

of the Caddo Homeland, away from the relatively narrow river

valleys, there are deep sandy soils that are not very fertile

and dry out quickly during droughts.

From early historic records we know that much

of Southeast Texas, particularly along the coast and major

bay systems (and adjacent inland areas), was occupied by non-Caddoan

speakers such as the Bidai, Atakapa, and Akokisas peoples.

The archeological record suggests that the historically known

patterns began developing thousands of years ago, certainly

by Woodland times.

In the early 1990s, Dee Ann Story called attention

to the archeological similarities across much of Southeast

Texas, especially the shared sandy paste pottery tradition,

and termed this pattern the Mossy Grove cultural tradition.

While the Mossy Grove tradition can be traced into historic

times, our interest here is on the Woodland or "Early

Ceramic" period, beginning by at least 200 B.C. and probably

earlier. Unfortunately for our present purpose, the archeological

sequence of the coastal Mossy Grove culture is much better

known than that present within the southern part of the area

we recognize as the Caddo homeland.

The hallmark of Mossy Grove culture, its sandy

paste ceramic tradition, was probably introduced or inspired

by the Tchefuncte culture in the LMV as is evident from finds

of Tchefuncte-like pottery at both coastal and Inland Mossy

Grove sites. In contrast to the thick-walled, flat-bottomed

plainwares of Fourche Maline, Mossy Grove peoples created

relatively thin-walled, round- or conical-bottomed vessels.

The double-bitted axes and polished stone artifacts found

in Fourche Maline sites are absent. Mossy Grove projectile

points include small Gary and Kent dart points and, after

about A.D. 500-600, expanding stem arrow points of the Friley and

Scallorn types. These artifacts and various knives (bifaces)

and heavier chopping tools are made of poor quality local

materials, often petrified wood. Another local raw material

for making chipped stone tools is Manning glass, a fused volcanic

material that outcrops in a narrow east-west band near the

southern limit of the Caddo Homeland just north of Huntsville,

Texas.

In the northern Mossy Grove area, along the

upper Angelina and Neches River valleys, Woodland sites are

very common and account for 25-50 percentage of the known sites. The

increase in sites compared to the Archaic period is also coupled

with a shift in settlement location from upland areas and

higher ridge tops to the low sandy ridges ("interfluves")

overlooking the confluences of small drainages. Archeologist

Jim Corbin has speculated that this shift may be tied to the

beginnings of gardening, although so far there is no direct

evidence of early domesticated plants. The sandy, acidic sediments

of the area make for poor preservation of organic materials.

Mill Creek Culture

In East Texas to the west and south of the Red

River and its tributary, the Sulphur River, Woodland archeological

sites seem to differ significantly from the Fourche Maline

pattern. For one thing there are far fewer Woodland sites

and those that are present are smaller and do not seem to have

the characteristically thick, black middens with abundant

Williams Plain pottery. The relatively small amounts of pottery

that the East Texas sites have is more varied; it is typically

thinner than Williams Plain and more often decorated with

incised lines, punctations, and other designs. Archeologist

Tim Perttula has argued that these and other differences

suggest that a distinct cultural pattern existed in the western

frontier of the Eastern Woodlands in the Pineywoods of East

Texas and the Post Oak Savanna.

The Mill Creek culture encompasses the period

from about 200 B.C. to A.D. 800 and is contemporaneous with

Fourche Maline and Mossy Grove, but different from either.

Sites of this culture are known mainly in the Big Cypress Creek

and Sabine River basins in East Texas, but apparently continue

eastward into northwest Louisiana. Because relatively few

Mill Creek sites have been recognized and investigated by

archeologists, the concept must be regarded as quite tentative.

(Like Mulberry River culture, Mill Creek culture is an idea that may or may not become widely accepted.)

Perttula hypothesizes that Mill Creek groups

moved around more (i.e., were less sedentary) than Fourche

Maline groups, based on the presence of only relatively small sites

and small middens. The fact that ceramics are not abundant

at Mill Creek sites compared to Fourche Maline or Mossy Grove

sites, may represents regional differences in food processing.

Mill Creek peoples appear to have relied on traditional cooking

and storage techniques such as pit-oven cooking and storage

pits rather than on ceramic technology. Mill Creek peoples

still practiced the hunting and gathering lifestyle of their

Archaic predecessors and relied heavily on nuts and deer.

No structures, burials, or burial mounds have yet been identified

at Mill Creek sites. Stone tools include small Gary and Kent

dart points eventually being replaced by expanding-stem arrow

points about A.D. 600-700. Ground stone tools, particularly

manos and pitted nutting stones are common. Double-bitted

"axes" are uncommon as are other potential gardening

tools. Most stone tools are made of local quartzite, sandstone,

siltstone and petrified wood.

The best known Mill Creek site is the Herman

Bellew site, which overlooks Mill Creek, a tributary of the

Sabine River in northern Rusk County. The Woodland ceramics

from the site include sandy paste, grog-tempered, and bone-tempered

sherds, a relatively high percentage of which are decorated

(6 percentage compared to less than 3 percentage for most Fourche Maline sites).

Despite relatively extensive excavation, only 225 sherds were

recovered at Herman Bellew. In comparison, many Fourche Maline

sites have yielded thousands of sherds.

According to Perttula and archeologist Linda W. Ellis, Mill Creek pottery differs from the

typically thick, grog-tempered Williams Plain. Instead, there

is a mix of sandy paste wares, bone-tempered wares, and thinner

grog-tempered wares, primarily plain. Mill

Creek groups may have adopted ceramic ideas and technologies

from the two neighboring Woodland cultures with whom they

were interacting. From the Fourche Maline tradition came grog-

and bone-tempered pottery with mainly flat-based bowls and

jars combined with the Mossy Grove tradition of non-tempered

sandy paste wares with round-based vessels. Alternatively,

the apparent borrowing from adjacent cultures may simply be

changes through time in manufacturing technique and vessel

shape that represents the evolution of ceramic use for different

purposes by Mill Creek peoples.

Another important difference between Fourche

Maline and Mill Creek is the presence in the latter of rock

hearths and storage pits. Small rock hearths (probable earth

ovens) and larger concentrations of fire-cracked cooking stones

were found in Woodland contexts at Herman Bellew, suggesting

that the Archaic pattern of using hot rocks to cook plant

foods (especially roots) was still prevalent. Another example

of a continued Archaic pattern is a large storage pit dating

to about A.D. 100-200.

Woodland Summary:

What can we say about the cultures that came

just before the Caddo? While a great deal remains to be learned

before we can trace the early ancestors of the Caddo people,

some of the larger patterns seem clear. Woodland peoples were

living throughout Caddo Homeland for over a thousand years

before A.D.800-900, the period when the Caddo cultural tradition

is first recognized by archeologists. During the 1300 years

between 500 B.C. and A.D. 800, Woodland peoples in the region:

- • expanded their numbers and populated the

area more densely

- • became increasingly sedentary and established

semi-permanent settlements, including villages

- • adopted ceramic technology for cooking and

storage

- • began a distinctive ceramic tradition with

elaborate forms and incised designs

- • began to cultivate squash/gourds and starchy

and oily seed plants

- • adopted the bow and arrow and stopped using

the atlatl and dart as the principal weapon

- • acquired exotic items from distant sources

(Hopewell/Marksville network)

- • treated their dead in increasingly elaborate

ways

- • established burial mounds and the first platform

mounds at ritual centers

- • developed hereditary political and religious

leadership

These developments and changes were not simultaneous,

and they did not take place all across the region. We still

do not understand either the exact sequences of development,

or the processes of change. In a sense most of these Woodland

elements were different parts of the same general process:

the transformation from small egalitarian groups of mobile

hunters and gatherers to larger, ranked societies who depended

on agriculture.

The Fourche Maline culture of the Red River

valley was almost certainly the main "mother" culture

out of which the Caddo cultural tradition evolved. But that

does not mean that all of the ancestral Caddo groups were part

of the Fourche Maline tradition. Ancestral Caddo peoples may

have been responsible for the Mill Creek culture to the south

and west of the Fourche Maline. Mossy Grove culture, on the

other hand, probably represents the ancestors of non-Caddo

peoples, but they were clearly interacting with Mill Creek

and Fourche Maline peoples. Said differently, Woodland groups

across the Caddo Homeland developed localized ways of doing

things that had their origins long before A.D. 800. The smaller

groups that lived on the western and southern fringes were

probably perceived as being akin to "country hicks"

(or perhaps even enemies) by the larger, more mainstream groups

that lived in the Caddo "heartland"—the Red

River Valley at and below the Great Bend.

|

Reel-shaped copper gorget and copper

bracelets from Jonas Short. Similar reel-shaped artifacts

are known from early Marksville burial mounds and in

burial mounds of the Adena culture of the Ohio River

valley far to the northeast. TARL archives.

|

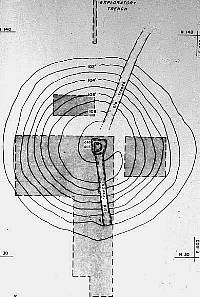

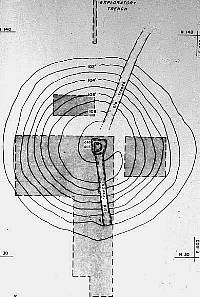

Map showing area excavated at the

Jonas Short Mound. TARL archives.

|

|

|

These boatstones from Jonas Short

Mound are made from syenite and probably come from outcrops

near Little Rock, Arkansas. The smooth river pebbles

in the one on the right are still in the original find

position within the boatstone. These probably served

as rattles held within because the boatstone was tightly

affixed to its atlatl. This lends additional support

to the notion that atlatls with exotic boatstones were

strictly ritual objects—what hunter would want

his presence announced by a loud rattle? TARL archives.

|

Apparent artifact caches found within

Jonas Short Mound may have once been associated with

cremated burials. If so, the evidence was not preserved.

The syenite boatstone is obviously a ritual artifact,

but the smaller bits look like ordinary debris. TARL

archives.

|

Coles Creek-like pottery from the

Pace site on the Louisiana side of Sabine River just

above Toledo Bend Reservoir. TARL archives.

|

Buried Fourche Maline midden exposed

in excavation wall at the Crenshaw site. Although the

dark stain of this midden is clearly visible, some Fourche

Maline middens are so dark they are described as being

black. Courtesy Frank Schambach.

|

Polished stone celts and grooved

axe from Fanny Snipes site. The celts probably date

to Late Woodland or Early Caddo times, while the grooved

axe is probably a much older Archaic artifact. The Snipes

site, like many sites in the Caddo Homeland, has a mixture

of artifacts dating to different periods. TARL archives.

|

French Fork Incised jar from a Fourche

Maline context at the Crenshaw site, Miller County,

Arkansas. Although this is a Coles Creek style commonly

found in the lower Mississippi Valley, it was probably

made locally by Fourche Maline potters. Photo by Frank

Schambach.

|

Unique four-chambered Fourche Maline

pottery vessel from the Crenshaw site, Miller County,

Arkansas. Dozens of unique pots have been found at this

site that are unlike any known elsewhere. The inventiveness

of the Crenshaw Fourche Maline potters anticipates that

of early Caddo potters. Photo by Frank Schambach.

|

Bottom view of unique four-chambered

Fourche Maline pottery vessel from the Crenshaw site,

Miller County, Arkansas. Photo by Frank Schambach.

|

Cone-shaped sandy paste vessel from

a Mossy Grove site in Polk County, Texas. Whole Mossy

Grove pots are rare. TARL archives.

|

| |

Nutting stones and grinding slabs

such as these are found in Woodland as well as Late

Archaic sites in the Caddo Homeland. TARL archives.

|

Manning Fused Glass, a volcanic material that outcrops

in a narrow east-west band near the southern limit of

the Caddo Homeland just north of Huntsville, Texas. This

material was used by local Caddo peoples to make stone

tools. It is, however, characteristically fractured, as

this piece is. It is also usually found in small nodules.

This example is the largest known nodule of Manning Fused

Glass, measuring about a meter across (39"). Photo

by Ken Brown. |

|