USDA forest workers

continue to search for chemical compounds

that will remove graffiti painted on

the porous concrete walls of the mill

ruins.

|

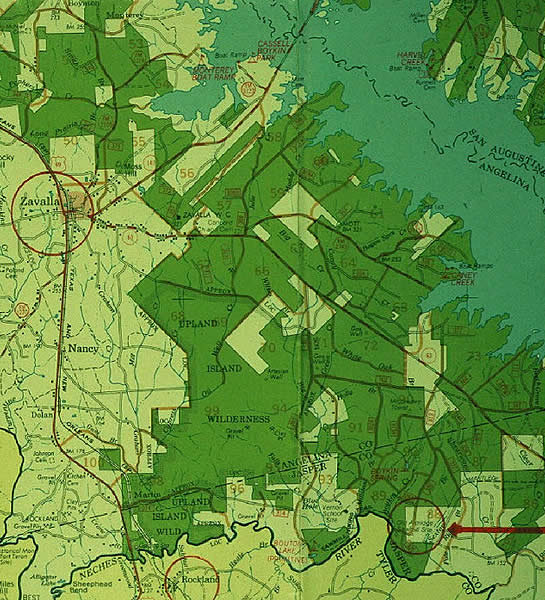

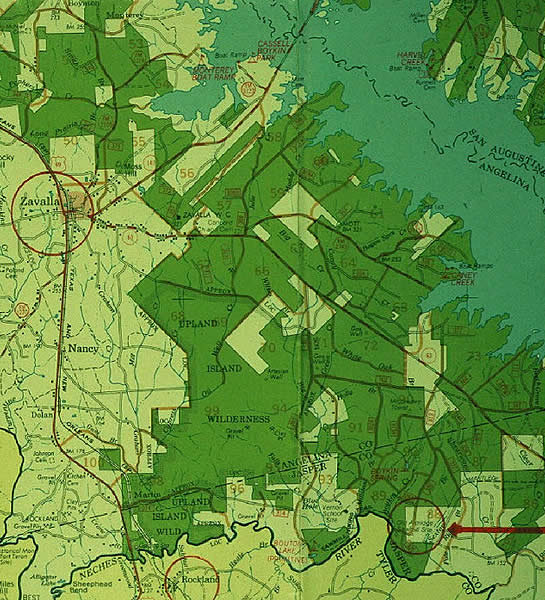

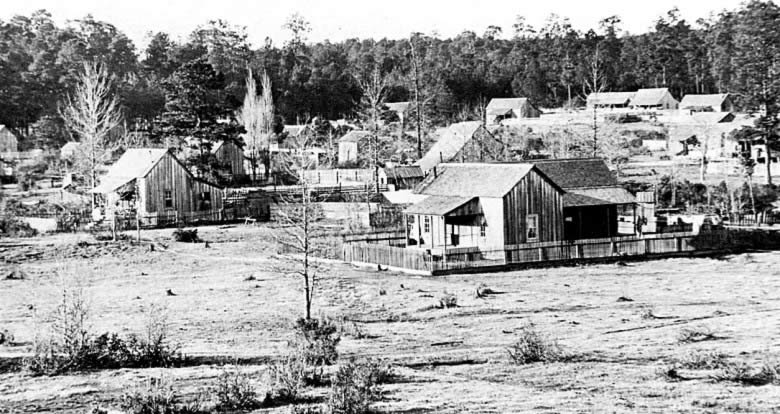

The Aldridge Sawmill and Township

site (circled in red, lower right) is located in the

longleaf pine woods of the Angelina National Forest

in East Texas. It sits on a high terrace adjacent to

a scenic bend of the Neches River in the extreme northeastern

portion of Jasper County. Click to see full image.

|

A driver maneuvers

a flatboat ferry across the river at

Aldridge.

|

|

Recollections of Mittie Mae Blake Dykes,

age: 102 1/2

Mittie was born in 1894, in Angelina County, Texas.

She had 5 brothers and sisters, most of whom died early

on of pneumonia. She recalled that Aldridge had "nice

houses and a nice big school," with many children

going to it. Everyone around worked in the mill, whites

and blacks together. "There was a big kitchen at

Aldridge where you could buy dinner" (the noon

meal). They also had a doctor's office, drug store,

barber shop, and a kitchen—"a big, long house

with big, long tables and benches on each side."

The main cook was a man, and about 10 women worked with

him there from daylight until dark. According to Mittie,

she didn't ask to work in the kitchen; they "just

came and got her." Someone had told them she could

cook.

Mittie's husband Jess was a carpenter who worked outside

the mill. He made furniture and also worked at the blacksmith

shop. Jess played the fiddle for the dances at Aldridge

and other places, and Mittie liked to dance. They were

married in May, 1918. Jess died in 1940 at age 50, from

pneumonia.

--(Interview by Faye Green, October 16, 1996.)

|

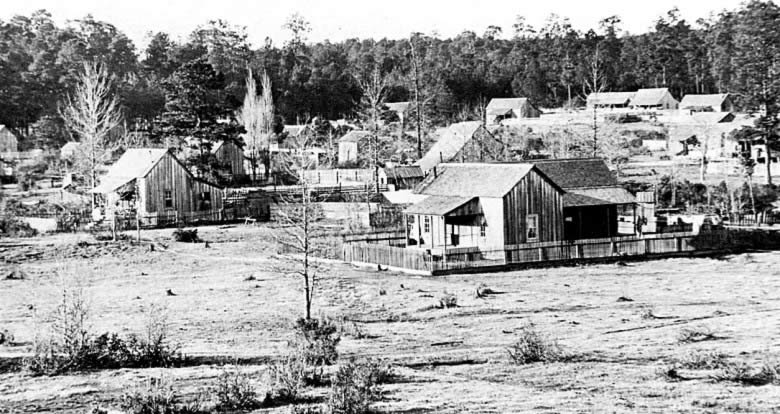

Company houses provided

for both white and African -American

workers were described as "comfortable,"and

likely resembled those in this photo

of the "colored quarter" in an unknown

milltown. Photo courtesy Stephen F.

Austin State University Forest History

Collections, Thompson Photo Collection.

|

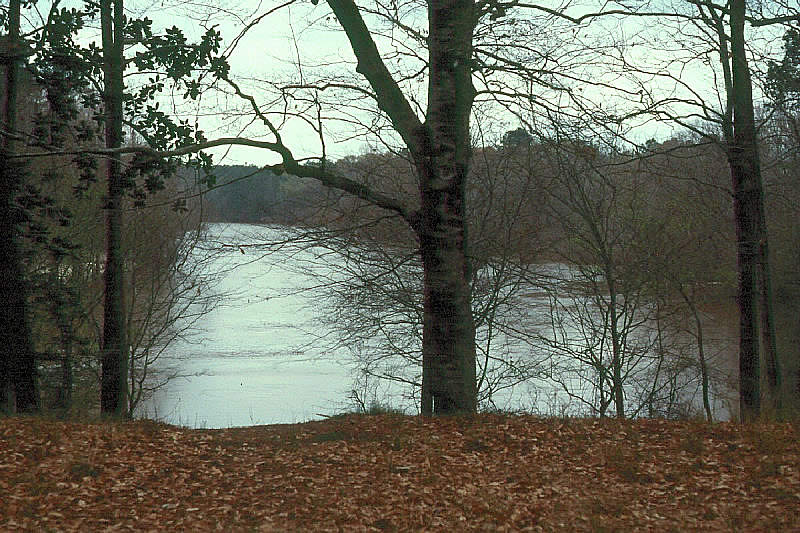

A tranquil scene

of the Aldridge millpond. Click to see

full image.

|

A fishing scene at

a muddy river in East Texas, near the

turn-of-the-20th century. Photo courtesy

of Texas Tides digital collection (TXK

p86n2).

|

|

There is no sign of residential structures, school,

churches, commissary or hotels—only second—growth

timber now stands where a community once thrived.

|

|

Forest workers, historians, and East Texas residents

have long been aware of the slow cycle of destruction occurring

at the Aldridge Sawmill site. Hidden deep in the Angelina

forest, the high-walled ruins are a magnet for "artists"

wielding spray-paint cans and artifact hunters seeking items

left behind by millworkers and townspeople nearly a century

ago. Nature has taken its toll as well; vines crawl over the

porous concrete walls, and shrubs and trees have invaded the

building interiors.

Measures to stabilize, investigate, and protect

the Aldridge site—one of the few remaining sawmill ruins

left in East Texas forests—have been in the works for

over a decade, although lack of funding and manpower continues

to slow progress. Volunteer efforts have helped turn the tide.

During a two-week period in 1995 and 1996, the USDA Forest

Service, National Forests and Grasslands of Texas, hosted

a Passport In Time (PIT) project focusing on the Aldridge

Sawmill and Township. Volunteers from across the United States

came to help with the investigations at the site. During that

time, visitors coming to view the ruins told of their family

members who had lived or worked at Aldridge.

The following "snapshot"

of the Aldridge Sawmill and community—as

it appeared in the past and as it appears

to visitors today—is based on information

collected from these efforts as well as historical

research and oral history interviews conducted

by the USDA Forest Service staff.

Boom and Bust

Hal Aldridge was a young entrepreneur

from Rockland, Texas, where he first gained

experience as a sawmill owner and operator.

He bought the Rockland sawmill in 1890, and

as this mill prospered, he began to purchase

lands with "high quality" timber

(undoubtedly longleaf pine) in Angelina and

Jasper counties. With a vision of building

a mill closer to his new timberland holdings,

Aldridge sold the Rockland Sawmill in 1898.

He chose the site for his new mill carefully,

locating it on the east bank of the Neches

River at a bend downstream from what was once

known as Boon's Ferry crossing.

At that time, the river-bend site already had

a logging history. Since the 1840s, it apparently had been

a gathering and shipment point for rafting logs down the Neches

River to the coastal city of Beaumont. The river would continue

to be an important factor in the new sawmill—the water

was used for boilers, train engines, and for fighting fires.

The river channel provided transportation and storage space:

logs were floated downstream, and log booms could be set up

to store logs for future production. There were two other

important resources to be exploited in this area; the lumber

produced from the pines and the rocks from the nearby quarries.

After the great hurricane nearly destroyed Galveston in the

early 1900's, rock from the quarry near Aldridge was used

to build the long barrier jetty.

Another critical factor was veteran lumberman

John H. Kirby's plan to build an east-west railroad to the

site of Aldridge Mill. As a landowner in the area, Kirby had

an eye on future business development. By building the Burrs

Ferry, Browndell and Chester Railroad (BFB&C), he could

ensure that products would reach their markets.

Hal Aldridge, however, did not

wait for the railroad to be built. He began

building the wooden sawmill in 1903, completing

construction by 1905. A Herculean effort then

ensued to outfit the remote site: hundreds

of men and tons of machinery were brought

in. Four massive boilers were hauled by oxcarts

with huge wooden wheels through the forests

to the Aldridge Mill. Concurrently, work proceeded

on building the railroad. By 1906, the BFB&C

Railroad extended to the rock quarries just

northwest of Aldridge and, a year later, finally

reached the sawmill. This 11-mile tram line

ran from Rockland, to Aldridge, to the Neches

river.

The sawmill enterprise at Aldridge got underway

successfully, with production reaching 75,000 board feet of

lumber daily. But the wooden mill buildings were crowded,

unsafe, and proved to be a fire hazard. On August 25, 1911,

the mill burned to the ground.

At this time, the Aldridge mill was the only

sawmill operating in the vast timber region. Other mills had

already closed, and the decision to rebuild seemed a wise

business strategy. To ensure greater safety and avoid increased

insurance rates, the layout of the mill was changed to provide

adequate spacing between the buildings. By 1912, the mill

had been rebuilt, with buildings to house the engine, boiler,

fuel room, and dry kiln constructed primarily of concrete

reinforced with iron beams and furnished with state-of-the-art

machinery, including a single-cutting band saw and a resaw.

With the new improvements, the Aldridge Lumber

Company once again saw success. In a short time, the mill

was producing 125,000 feet of lumber a day. Hal Aldridge employed

500 workers, some harvesting timber in the woods, others working

at the mill—the largest roster of any lumber company

at the time. And as the mill rose from the ashes, so did the

town. By 1913, some 1000-1500 folks lived in 200 company houses

in the quiet, neatly arranged community of Aldridge.

Segregation in towns and cities was common,

and Aldridge and other sawmill communities were no exception

even though black and white workers often worked side-by-side

in the woods. Accommodations in both the "colored"

area (the area reserved for African Americans) and "white"

area were described as simple frame houses with wide front

porches. (Mill owner Hal Aldridge, however, built what is

described as a rather "palatial mansion" for himself.)

Although some descendants of former residents recall that

homes rented to white workers were somewhat nicer than those

for blacks, no one interviewed recalled racial tension or

labor disputes in the small community.

A central focus of the town was the company

commissary, where workers could purchase food and furnishings

with discount tokens provided by the mill. There was also

20-room hotel for travelers, a post office, blacksmith shop,

train depot, two schools, shops, saloons, and other typical

enterprises found in small towns. A large community vegetable

garden provided free produce for the workers.

But success and prosperity at Aldridge again

were to be fleeting. On October 22, 1914, the mill was struck

by an arsonist. Twice hit by misfortune, Hal Aldridge elected

to quit the lumber business and move to EI Paso, leaving his

operation in care of company Vice President F. W. Aldridge

(assumed to be Hal Aldridge's brother.) Fortunately, the October

22 fire had been discovered shortly after it started, and

only minimal damage was done. Nonetheless, business at the

mill began trending downward, most likely due to the depletion

of the pine forest in the area. And in 1919, yet another fire

delivered the final death blow to Aldridge.

By 1920, the town of Aldridge was nearly abandoned. Kirby

Lumber Company eventually bought the mill, and a few loyal

and faithful Kirby employees kept the mill operating. During

the next decade, they built houses using wood from the mill

houses, fenced the living areas, and farmed the land, according

to 1990s interviews with residents. But in 1927, the railroad

spur from nearby Rockland to Turpentine was closed, further

blighting efforts to rekindle enterprise at Aldridge. The

U. S. Forest Service eventually took possession of the property,

and it was annexed into the Angelina National Forest.

In 1941, the Forest Service replanted the area

immediately next to the sawmill. In subsequent years, staff

have taken measures to document the historic site, replant

trees, and manage and abate insect infestations (the general

practice was to cut and leave on the ground those pine trees

infested with the southern pine beetle). The pine forest to

the north of the sawmill, where the "white" residences

were, was cut a second time, and the land is currently producing

a third (historically) generation of pine. The last planting

took place in 1984, and the resulting pine plantation is nearly

impenetrable.

Ruins in the Woods

|

|

In this section:

|

Working with a USDA

Forest Service staff person, volunteers

from the Passport in Time project dig

shovel tests in the Neches River terrace

adjacent to the Aldridge sawmill ruins.

The soil is sifted through screens for

small artifacts.

|

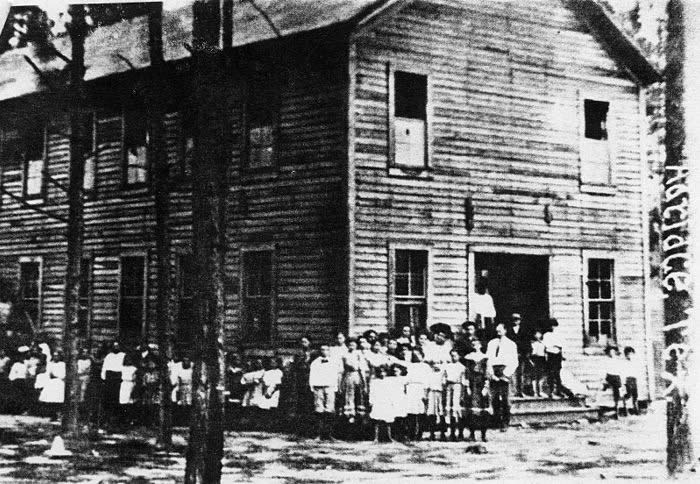

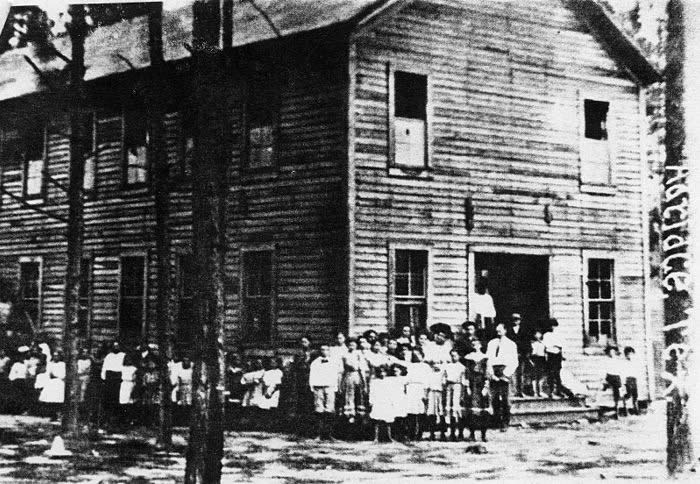

School at Aldridge,

date unknown

|

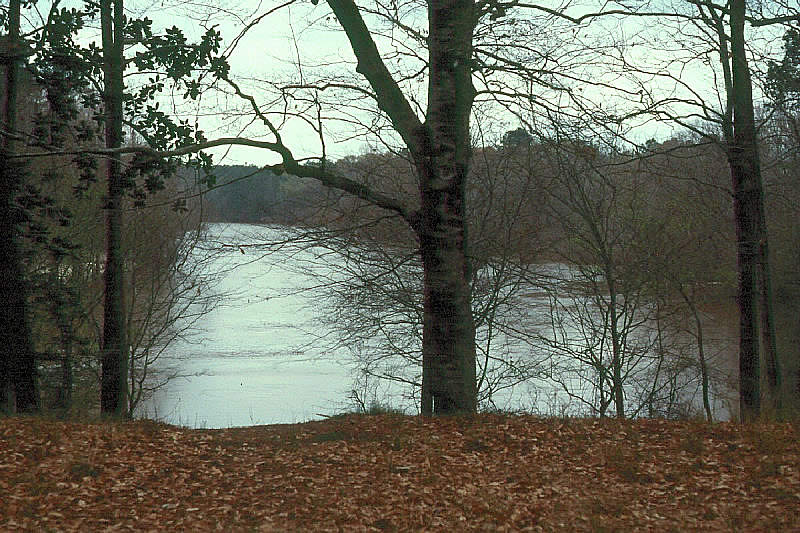

The Neches River near the Aldridge

site. The river was a critical factor in siting the

sawmill, providing water for the mill boiler engines

and a route for boat transportation in its deep channel.

|

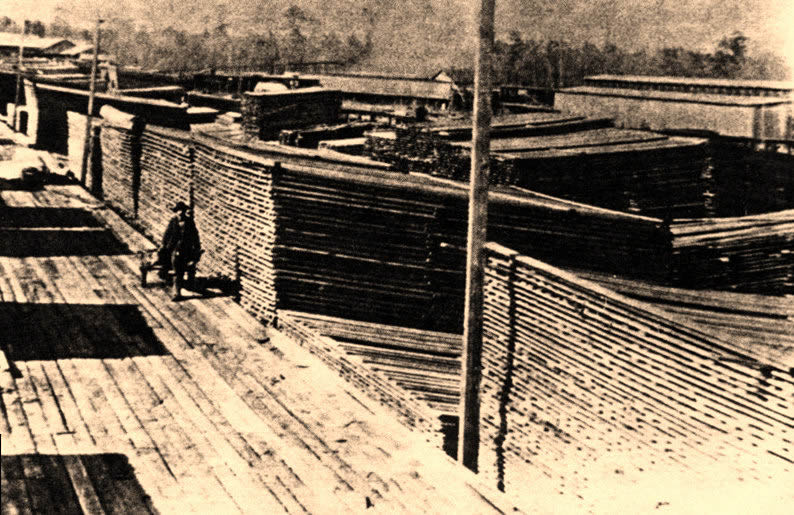

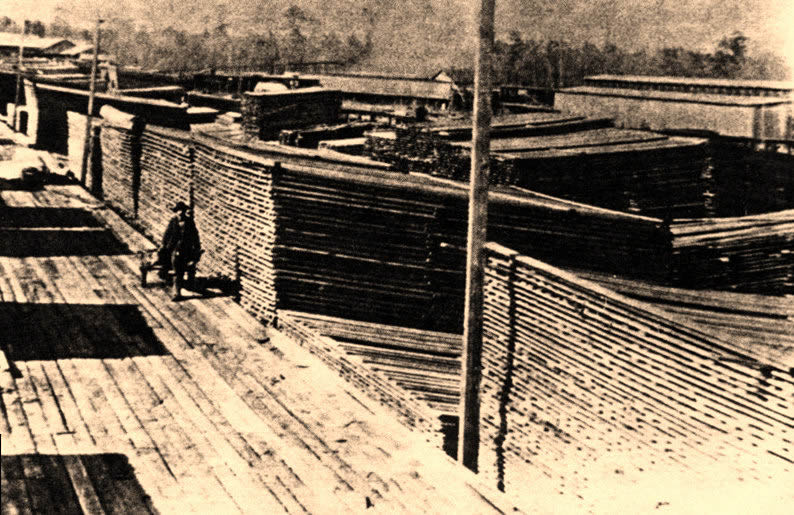

Flanked by piles

of pine lumber stacked high on each

side, a worker walks through the Aldridge

lumberyard.

|

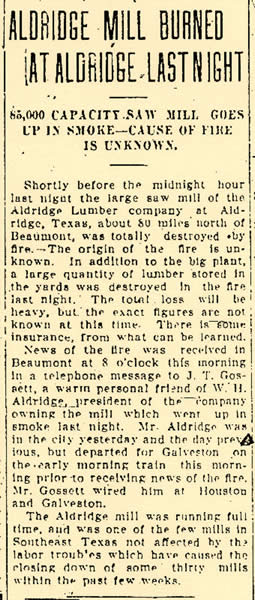

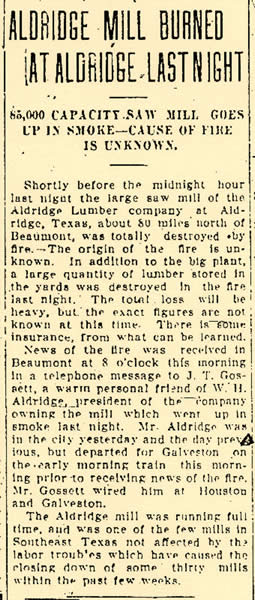

"Mill Goes Up in

Smoke." News account of the first Aldridge

sawmill fire, of unknown cause, as reported

in the Beaumont Journal, Aug. 26, 1911.

Click to enlarge.

|

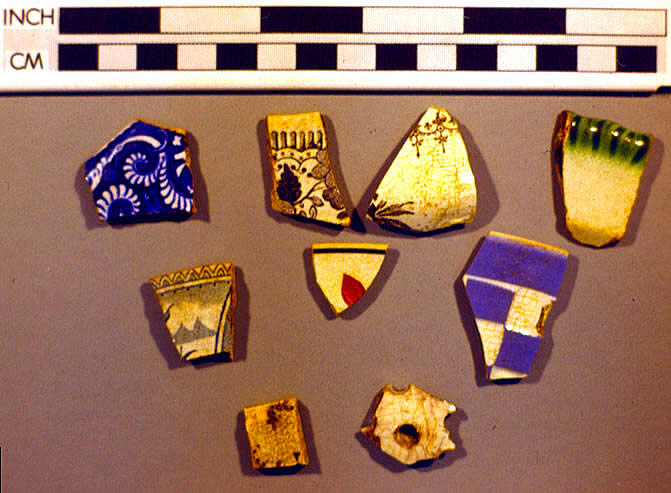

Tokens excavated

by PIT volunteers during Aldridge site

investigations. The "punch outs were

paid to Aldridge Lumber Company employees

and could be redeemed for a 10 to 20

per cent discount on merchandise in

the huge Aldridge commissary. Photo

courtesy USDA Forest Service.

|

|

Recollections of R.Z. Hinson, age 79

R.Z was born in 1917 in Aldridge Sawmill Town. He

recalls that he and his family lived in a frame board

and batten house with four rooms, a wood heater, and

a front porch. The houses were fairly close together,

and there was a well between every second house and

the next. They had "colored" quarters and

white quarters. For Fourth of July at Aldridge, they

would spend the week before fishing in the river, and

kept the fish alive in a box in the water. Then they

would have a big fish fry behind grandpa's house on

the river. His grandpa once caught a 49-pound cat fish

with clabber milk for bait, tied up in a rag in a net.

-- Interview by Fay Green, May 22, 1997.

|

|