Roots and Road Foods: Deep South Texas and Beyond

Route of Cabeza de Vaca through South Texas, Mexico, and Trans Pecos Texas. At right, native women cook meat in a gourd vessel using hot rocks as a heating element. Painting adapted from mural by Nola Davis, courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. |

|

|

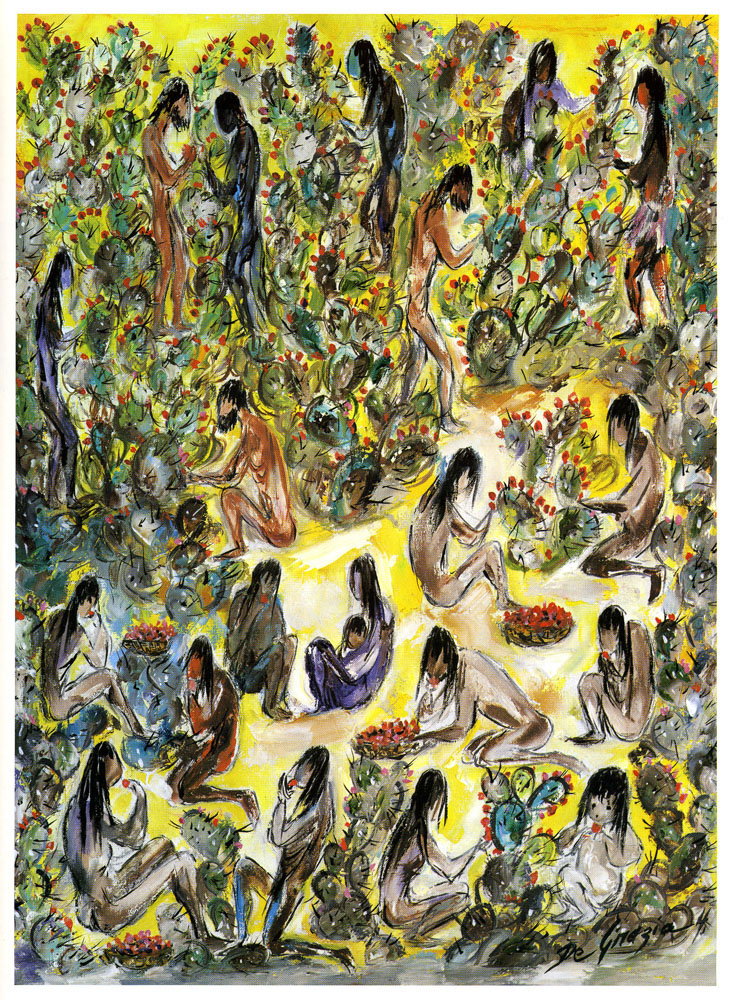

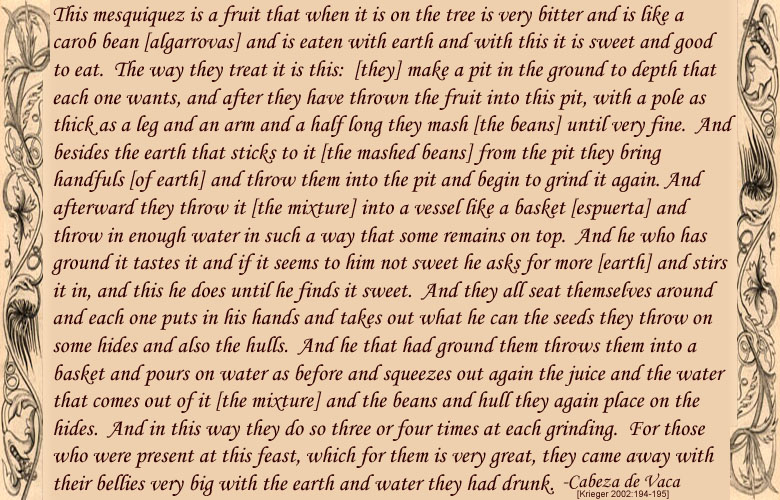

At the point where they crossed the Rio Grande, which likely was in the vicinity of today´s Falcon Reservoir, the trekkers stayed a short while in a village, what Oviedo called a “town” with 100 dwellings. A few miles to the south and up the San Juan valley, they visited another town, this one with 70-80 dwellings. According to Oviedo's account, the people in this region also relied heavily on tunas and deer as well as mesquite beans. In exchange for their curing endeavors there, the trekkers received 28 loaves of mesquite “flower.” Nothing was written about how any of these foods were cooked. From the Rio Grande south and west all the way to near the confluence of the Rios Conchos and Grande, tunas continued to be a mainstay. Also growing in abundance in northeast Mexico and throughout much of the Edwards Plateau were lechuguilla and sotol, Agavaceae family plants with edible “crowns.” Archaeological records from this region reveal that the sweet tasting crowns had long been staples. Ethnohistoric accounts from the 17 th and 18 th centuries attest to the crowns being baked for two days or so in earth ovens. Oddly, accounts by the trekkers did not mention these plants as an important food source anywhere in Mexico’s northern tier. Had they eaten them, they surely would have commented on their sweet taste. Moreover, it does not seem likely that they would have confused the often dense patches of agave and sotol with what they reported as sparsely-occurring, bitter-tasting roots. When they traversed northeast Mexico, especially when they were south of the Trans-Pecos and Big Bend country, the bison-hide trade was in full swing but they did not report eating bison. It was the “Cow people” and their neighbors along the Rio Grande and its tributaries who hunted the bison and introduced the hides into the trade networks of what is today northeastern Mexico. Presumably their hunting grounds encompassed the dry grasslands of the southern Edwards Plateau and Trans-Pecos basin and range country. South of the Rio Grande, the trekkers encountered Indian people who also relied heavily on rabbits and hunted deer in the nearby mountains. Rabbit and deer meat was cooked in earth ovens. It can be inferred from Cabeza de Vaca´s comments that cooking time was no more than 10 hours. Some of the groups they encountered in what Krieger believed to be the San Juan River basin south of Falcon Reservoir used bottle gourds “that floated to them on the river.” To the west of there, along the southern tributaries to the Rio Grande, the trekkers encountered farming peoples who lived in permanent houses and ate beans and melons. This was the first time, since leaving the forested land of La Florida, that they encountered farmers. Among the groups who lived in permanent houses and relied heavily on cultivated beans and squash were those who left their villages seasonally to hunt bison. Cabeza de Vaca referred to these people as “those of the cows” because they killed so many bison and it was among them that, for the first time, he observed an exotic cooking technique, stone boiling. |

|

|

|

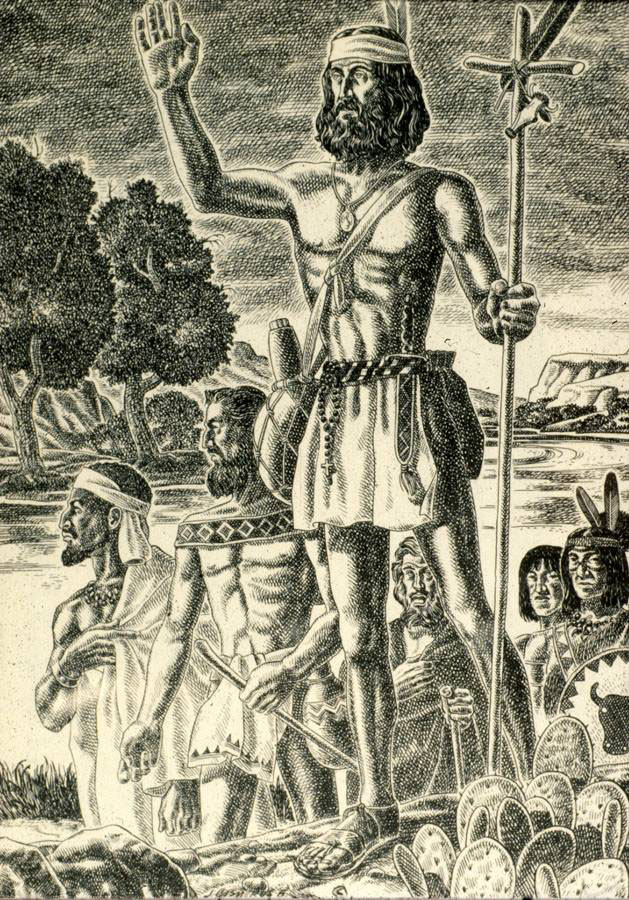

When Cabeza de Vaca and those accompanying him continued on their way across north-central Mexico, they encountered many farming communities, and on one occasion they were given “a great amount” of corn products, squash, beans, and cotton blankets. In this region, there was also an abundance of deer, and deer hides were important as trade items. As they neared the Pacific coast, Cabeza de Vaca reported that native agricultural practices had been curtailed severely insofar as the Indians had deserted their villages, which had been burned by Spanish slave hunters. The people there, along with Cabeza de Vaca and those traveling with him, found themselves in the midst of the initial conquest of this region of the New World, displaced and hungry but temporarily safe and satiated by wild roots. It was a thing that we held in great pity to see the land very fertile and very beautiful and very full of waters and rivers and to see those places deserted and burned and the [remaining] people so weak and sick, all fleeing and hiding away. And because they were not planting, with such hunger they subsisted on the bark of trees and [on] roots. This hunger in part reached us all along this trail, because they could ill provide for us being so miserable that it seemed they wanted to die. They brought us robes [mantas] that they had hidden because of the Christians and gave them to us and even told us how at other times the Christians had entered that land and had destroyed and burned the towns and carried away half of the men and all of the women and children and that those who managed to escape from their hands were going about in flight. -Cabeza de Vaca (Krieger 2002:228) The Indians on the road with Cabeza de Vaca when news of the Spanish slave hunters arrived undoubtedly expected Cabeza de Vaca to protect them from the wrath of the slavers. He endeavored to do so but, as the below quote illustrates, both he and the Indians knew how different the Old World trekkers had become from the conquistadores bent on subjugating, enslaving, and Christianizing the people of those lands. |

|

|

|

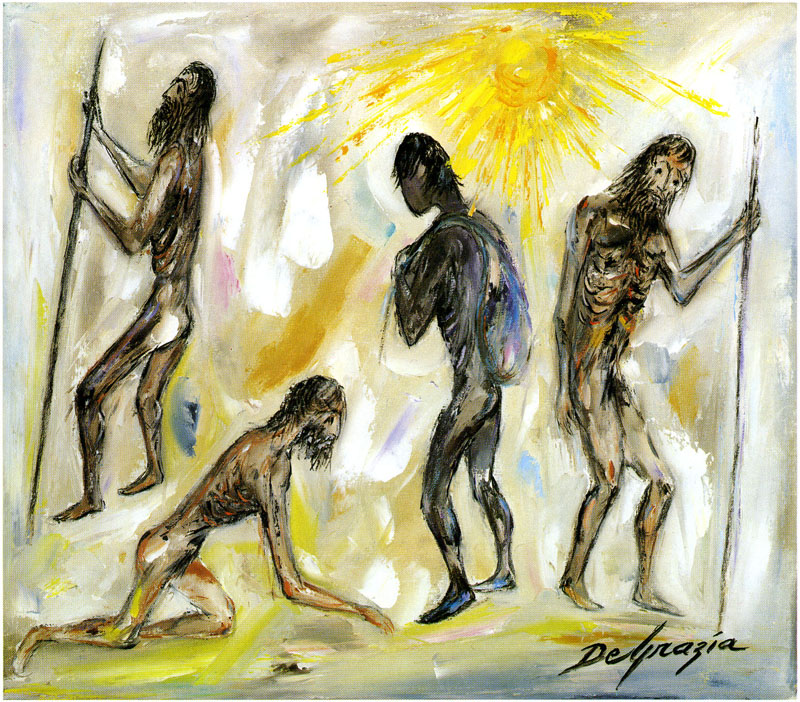

In deciding that Naked and Barefoot, extracted from the above quote, would be the working title for his forthcoming book Alex Krieger marked the tone of the New World into which the castaways had returned. In its final form, We Came Naked and Barefoot: The Journey of Cabeza de Vaca across North America revealed the fruit of Krieger´s painstaking analysis of the route(s) across the continent and, for me, beckoned assessments of the roots of native South Texas cookery. In Retrospect: “we in turn gave to others”Given the widespread states of military conquest and internecine conflict in the early 1500s, it is not at all surprising that shipwrecked soldiers of fortune along the Texas coast, noblemen and slaves alike, were seen and treated as prisoners-of-war. They were captured, arms and war booty in hand, by well-armed, numerically superior, better-provisioned, seemingly gigantic, militiamen who aimed to protect their village from would-be conquistadores. Some of the starving castaways were summarily executed by their captors; others were “brought back to life,” rehabilitated, and sold or traded to neighboring bands; several avoided captivity only to perish from exhaustion or starvation. The longest surviving POWs, our four trekkers and perhaps a few others who unceremoniously “disappeared” among the Indians, arguably accepted the state of affairs, with its requisite forced labor, and, for years, they planned their escape. Cabeza de Vaca and his fellow trekkers survived their ordeals as POWs and became successful healers and traders and effective, albeit not necessarily efficient, hunters and gatherers. Over the course of almost seven years, they came to know vast tracts of North America, root by root, fruit by fruit, and animal by animal, terrestrial and aquatic alike. During their cultural metamorphoses, the survivors had ample opportunity to learn enough about the landscapes and cooking technologies in greater South Texas to eke out a living along their routes to freedom. They made their escape when they entered the South Texas heartland for the last time and fled south to would-be enemies who welcomed the soon-to-be trekkers. In doing so, they availed themselves to the powers of Old World healers whose fame was spreading fast across South Texas. There may well be other perspectives from which to envision the success of this particular great escape. Might not it have been that, after years of service, the POWs unceremoniously became adopted members of their respective bands? They carried their own weight, shared their curing powers, and likely engaged in a bit of family-building of their own, although there is little to hint of that in the written accounts. In any event, their abrupt departure from custody may have been more akin to a difficult parting than a desperate escape from seasoned fighters and trackers who knew the regional landscape like the back of their hands. |

|