Rediscovering Heirloom Cookery:

Roots of South Texas Foodways

Foods, traditions, and technology. At top left, native peoples cook nopalitos ”cactus pads”in an earth oven, a depiction by TPWD artist Nola Davis. At bottom left, members of the Tap-Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation take part in a traditional drumming ceremony. Above, Alston Thoms works over a cooking fire and, at right, ethnobotanist Phil Dering harvests cattail plants for study. |

|

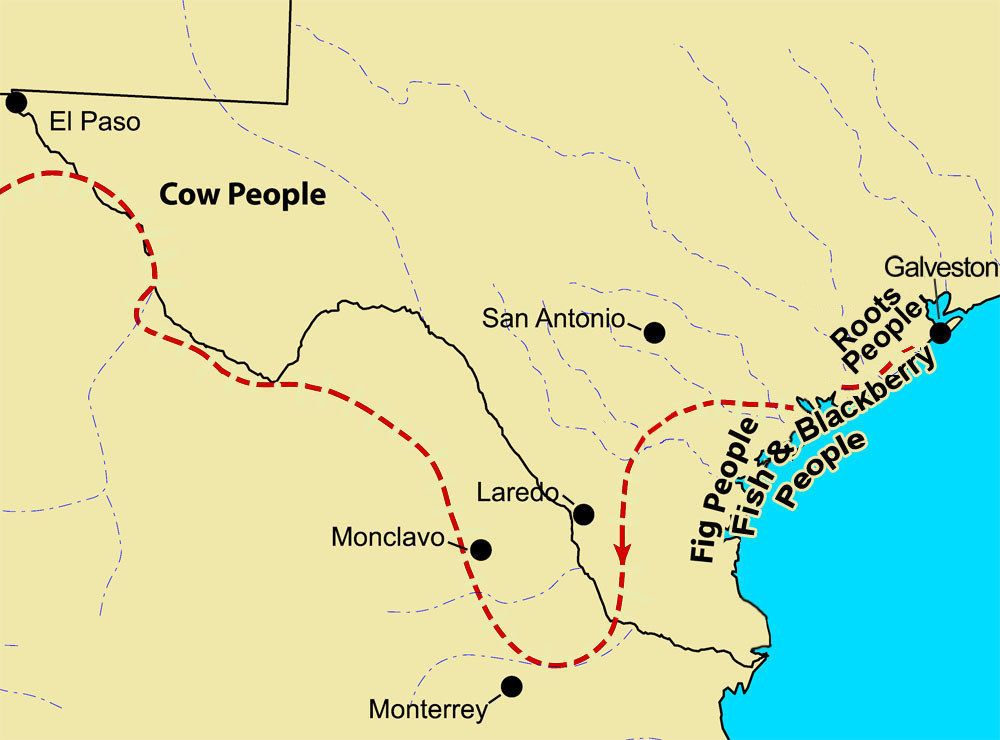

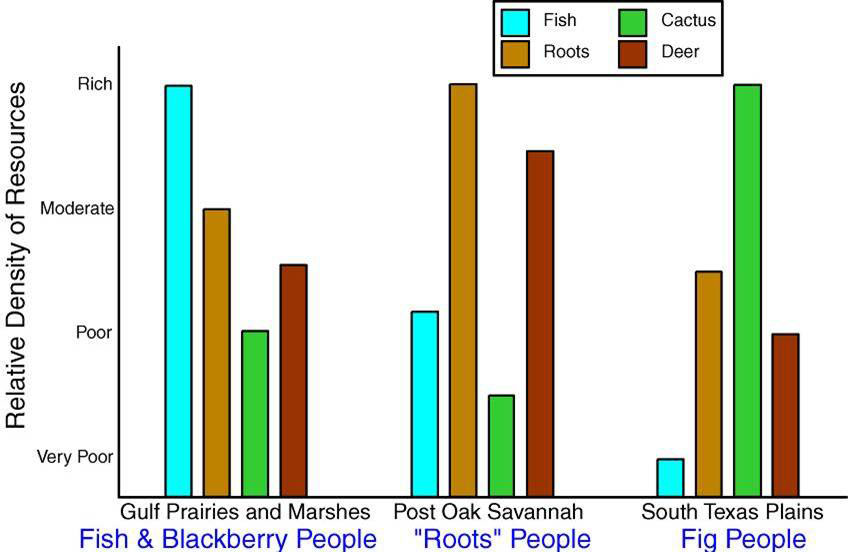

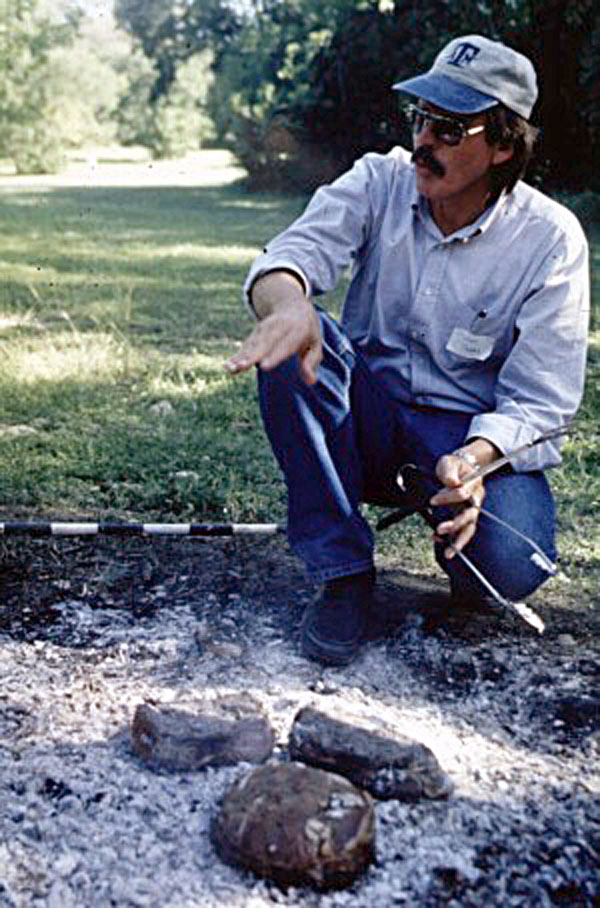

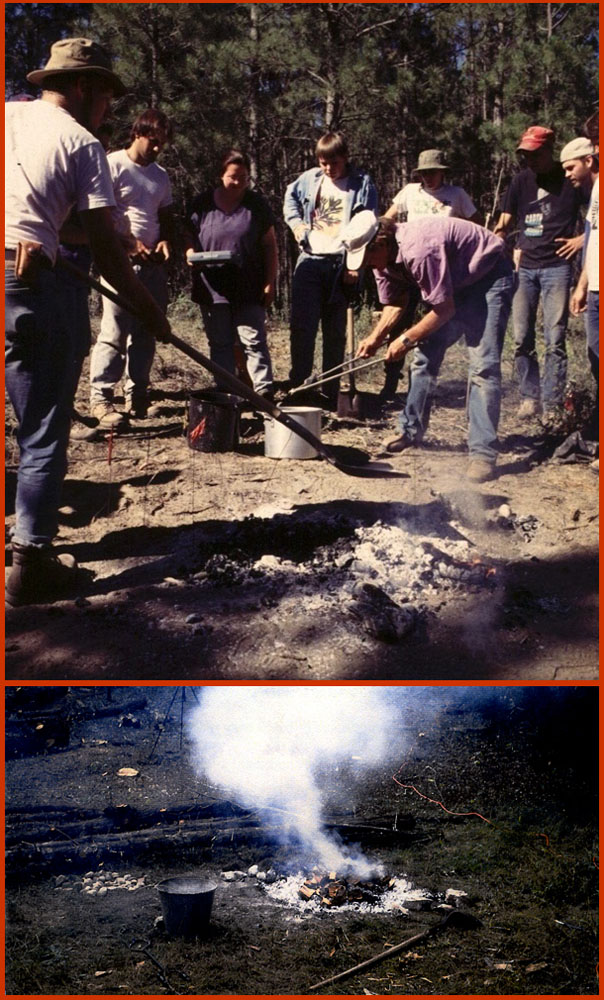

What can be gleaned from Cabeza de Vaca’s accounts of lifeways in greater South Texas at the dawn of written history in North America contributes significantly toward explaining archeological records in the same regions since the extinction of mammoths and other Pleistocene megafauna. The accounts provide sufficient information to rank the relative importance of stable food resources in the various ecological zones that comprise greater South Texas. In doing so, similarities and differences are readily apparent and provide multiple bases for generating and testing expectations about the nature of the archeological representative of diverse zones. As per various translations of his narrative, Cabeza de Vaca often referred to groups he encountered in a given area by a “food name” or, in one fashion or another, characterized some groups by their primary food resource. Accordingly, much of greater South Texas can be characterized in terms of its productivity potentials for deer, fish, roots, and prickly-pear cactus: (1) the "Fish and Blackberry People" lived in the Gulf Prairies and Marshes area, including on the barrier islands, and this region is rich in fish, with an abundance of deer and roots, and at least some access to prickly pear grounds; (2) the “Roots People” lived inland and probably exploited the outer edge of the Post Oak Savannah area, which can be said to be root-rich, deer-rich, and fish-moderate, with full access to prickly-pear grounds; and (3) the "Fig People," who relied heavily on tunas, lived primarily on the South Texas Plains, an area characterized here as cactus-rich, root-moderate, deer-moderate, and very poor in fish resources. Based on his own translations of the narrative and his knowledge of the joint report, Cyclone Covey in his 1993 book referred to the people along the coast who did not move very far inland as the fishing and blackberry-picking Indians. Included among these were the Han and the Capoque with whom Cabeza de Vaca lived on Galveston Island. Their staples during the winter months were fish, for two months, and roots, for five months, including those dug from beneath standing water and from canebreaks. Oysters and blackberries were staples during spring months. Deer were their primary game animal. They spent part of the year along the mainland. Cabeza de Vaca reports that the inland groups included the Yguazes whose “food supply is principally roots of two or three kinds and they look for them through all the country.” He did not apply a food name to any of the groups inhabiting this region, but for ease of comparison, interior groups are referred to herein as the “Roots People.” Oviedo summarized the importance of root foods as follows: “These Indians eat roots, which they take out from under the ground [during] the greater part of the winter. And [there] are very few [roots] and [these] are taken out with much labor, and the greater part of the year they suffer very great hunger. All the days of their life they must work at it [digging roots] from morning to night” (Krieger 2002:271). Pecans were also seasonally important as were freshwater fish. Deer were the primary game animal, and small animals were important as well. These mainland groups frequented both the outer and inner Gulf Coastal Plain. Cabeza de Vaca referred to one of the groups who live farther down the coast as the Fig People in recognition of their movements inland during the late summer to gather tunas in the South Texas heartland in the vicinity of the Avavares’ homeland along the south-most bend of the Nueces River well within the inner Gulf Coastal Plain. Many groups shared the vast prickly pear grounds of the inner Gulf Coastal Plains but throughout that region unnamed roots were the winter staple. On their way to the west coast, the Old World trekkers passed along the southernmost bison ranges, which extended almost to the Rio Grande, southeast of El Paso and northwest of Del Rio, in the greater Big Bend country. Some of the people there lived along the river in permanent houses, relied on beans, and squash, and seasonally left their villages to hunt bison. Cabeza de Vaca referred to a group that relied heavily on bison as “those of the cows” (or Cow People) and maintained that bison were also a staple resource for the people who lived 50 leagues up the Rio Grande. Linking History to EcologyDuring their last winter in Texas, in the aftermath of the brush-country tuna season and in the absence of fish or nuts, the erstwhile POWs (the Spanish survivors) followed age-old subsistence pursuits of digging and cooking roots. Their descriptions of wintertime digging provides a good deal of useful information about procurement and processing issues as well as size, shape, and taste of the roots. They, however, do not appear to have paid enough attention during the growing season to identify root foods by the plants' leaves or flowers, which would have facilitated their “proper” identification by Old World standards. In most cases, the above-ground and above-water plant parts “die back” in the winter and are said to be in a state of senescence as the roots ready for spring-time sprouting. My own limited success in identifying globeberry and winecup from their winter roots alone was years in the making and, in the case of globeberry, was not accomplished without the expertise of a well-trained specialist, Phil Dering. It is fitting then that plant ecologists have long placed the roots of greater South Texas cookery in the cryptophyte family of perennial herbaceous plants, those with perennating tissue completely concealed in the ground or at the bottom of water and well protected from the above-ground climate, as in the case of geophytes, helophytes, and hydrophytes. Interestingly, prickly pear, lechuguilla, and sotol, sometimes termed desert succulents, are classed as hemicryptophytes, perennial herbs with surviving buds at/near the soil surface that are afforded some protection from above-ground climate by a vegetation mat. From the coast through the heartland of South Texas and from the Brazos to the Rio Grande and beyond, roots were the primary wintertime staple, regardless of the availability of other plant foods, terrestrial game, or aquatic resources. To learn more about the elusive cryptophytes that sustained the survivors, their Coahuiltecan hosts, and their geographic ancestors through millennia, we need to know more about the ecology of the roots and fruits characteristic of the diverse ecological zones that encompass greater South Texas. We also need to better understand the variability in archeological records representative of cooking technologies evidenced in those zones. Where on the local landscapes do what kinds roots grow in what densities? How do the different root grounds respond to burning or heavy exploitation? How does the nutrient content of a given cryptophyte change from season to season? How do cooking requirements vary from root to root? We can learn a great deal about the roots and nature of South Texas cookery through actualistic experiments often termed ethnoarcheological investigations. In my own back yard experiments, for example, I have learned that a thick steak cooks to a delectable medium rare when placed directly on hot coals that have developed a blanket of white ash. On other occasions, I learned how to bake an evening meal of pot roast and a suite of geophyptes—potatoes, carrots, and onions—for three hours in an earth oven fired by four sandstone rocks, weighing about 5 lbs each, that were heated red hot in a nearby open-air hearth. Elsewhere in North America, working with archeology field school students and Native American cooks as advisors, we have learned that some roots and meat can be stone-boiled and rendered quite tasty in a matter of minutes. We prepared tasty “shish-kabobs” of fish and wild game and cooked them on a hot-rock griddle on an open-air hearth. On several occasions, we baked camas for 48 hours in earth ovens that transformed the white, relatively tasteless bulbs into sweet, fig-like morsels, which were about as nutritious as sweet potatoes. What my colleagues and I have learned in the Pacific Northwest and northern Rockies has direct relevance to South Texas cookery in part, because camas, dog-tooth violet, and onions grow in both places and likely have long been used as staples. Archeological Evidence of Ancient FoodwaysOviedo´s version of the joint report attests to the procurement of roots, deer, rodents, fish, and sundry other foods by Indians who “walk along the river the whole of winter up and down, and down and up, never stopping searching for food.” This description is in accord with evidence recovered from a number of archeological sites in south Texas, recording a way of life with basic elements unchanged throughout much of prehistory. At the Richard Beene site south of San Antonio, for example, given the overwhelmingly riparian-related nature of the tool-stone, cook-stone, feature, floral, and faunal assemblages at the site, Oviedo's statement readily accounts for the site´s overall archeological record, which spans the last 10,000 calendar years. What can be gleaned from the trekkers and reliably inferred from regional ecology about the relative abundance of staples along the Gulf Coastal Plain of greater South Texas—roots, prickly pear, nuts and fruits, fish and shellfish, deer and small game—leads one to expect considerable diversity in cooking-related features at archeological sites in general. Insofar as different foods have different cooking requirements and often are dependent upon on whether the items are green or ripe, young and tender or old and tough, or big or small, one must conclude cooking was more complex than can be accommodated by a single example of open-air hearths, earth ovens, or stone boiling containers and ceramic vessels. Oddly, the Spanish accounts never mention the use of rock heating elements—cook stones—in earth ovens or open-air hearths. It seems certain, however, that cook-stone technology was a requisite component of hunter-gatherer lifeways. We know, for example, that in areas where native stone was not readily available, the people there manufactured “cook stones” by baking lumps of clay until they became rock hard and presumably quite capable of capturing and retaining heat. Cook stones and their functionally equivalent baked-clay lumps would certainly facilitate steaming shellfish in an earth oven. It is their ability to retain heat for prolonged periods that renders cook stones indispensable for two-day root-cooking events. It is their fuel-sparing ability” the capture of heat that would otherwise be lost from fast-burning brush fuel”that renders cook stones especially useful in fuel-poor regions, including the coastal prairies and inland plains. It is the very utility of cook stones, together with the common use of stone as heating elements in dome-shaped European ovens that leads me to assume the word horno, as used in the accounts, encompasses earth ovens with rock heating elements that, along with other cook-stone features, produce an abundance of fire-cracked rocks (FCR) as byproducts. There are many ways in which hunter-gatherers and farmers use cook stones to prepare food, just as there are many ways to cook without the aid of cook stones. Using the Richard Beene site again as an example, the diversity of cooking-related features uncovered there is, on the whole, consistent with the diversity and seasonality of staples. The site contained 37 family-size cooking features (ca. .3-.6 m diameter), 18 large-size (.6-1.5 m diameter), and one very large (ca. 2 m diameter) cooking-related feature. These represent earth ovens with and without rock heating elements as well as open-air hearths with and without rock heating elements. It is also possible that some of the FCR features represented the remains of stone boiling activities. (For more on cooking features and stone boiling see the Richard Beene exhibit). At the Richard Beene site, faunal remains, with two exceptions, are entirely consistent with what the accounts tell us about deer, small game, and fish. They include: deer-sized bone, several deer and one pronghorn, rabbits, rats, squirrels, gophers, beaver, porcupine, canid, various birds, turtles, snakes, frogs and toads, fish, and mussel shells. No bison bones were found, and this absence is in accord with Cabeza de Vaca´s comments about the rarity of encountering bison on the Gulf Coast Plain. The first exception to the account, a minor one, is the occurrence of a single bone from a pronghorn, an animal not mentioned in the accounts. (This bone was found among the debris of a 7,000-year-old encampment at the Richard Beene site.) The second exception is a major one. Whereas there are no clear references in the accounts to river mussels being an important food resource, mussel shells are the most visible and most common food remain at the Richard Beene site, as they are at most sites in greater South Texas. What this disjunctive suggests to me is that Cabeza de Vaca and his fellow trekkers, participant-observers all, were sometimes as cryptic in their comments about foodways in general as they were in identifying cryptophytes on which they and their hosts depended. Foodways Depicted in Later AccountsOddly, in light of the demonstrated importance of root foods through the millennia in greater South Texas, cryptophytes seem to disappear from ethnohistoric records within a century or so of Cabeza de Vaca´s time. There is hardly a mention of geophytes in the 17th- and 18th-century historical accounts of hunters and gatherers in that region or, for that matter, anywhere in adjacent parts of northeast Mexico and the Edwards Plateau and Post Oak Savannah country. Confirmation that oven-baked cryptophtes were not likely among the region´s staples during the 1600s and 1700s comes from French soldiers and would-be settlers who established Fort St. Louis (1685-1688). They were familiar with the Gulf Coastal Plain between the Trinity and Nueces rivers although not nearly to the extent as Cabeza de Vaca and his fellow POWs. In any event, the French accounts fail to mention, other than in passing, anything about the role of roots in native cookery although it is clear that geophytes were a significant part of the flora. Henri Joutel, one of the French officers, observed, for example, that onions grew in abundance in recently burned areas and that the bulbs “were not larger than a thumb but as good as ours in France.” He also reported that “these Indians had some earthen-ware pottery [poteries de terre] in which they cook their meat and roots.” Consistent with his fellow European explorers and settlers, Joutel failed to identify any specific cryptophytes or estimate their collective significance in the local diets, although such may be implied by this seemingly routine comment about pot-boiled “meats and roots.” In common with Spanish explorers' accounts of the time and in marked contrast to Cabeza de Vaca´s accounts some 150 years earlier, were notations that bison were everywhere and that they seemed to be a mainstay for many groups along the outer Gulf Coastal Plain. Elsewhere, I have argued that apocalyptic declines in Indian populations from Old World diseases allowed bison to gain a foothold in the savannah regions. In that scenario, native people rebounding from a population nadir would not be effective enough as predators to over hunt and thereby expatriate bison from marginal savannah habitat. That would happen soon enough with the introduction of European horses and guns, which, in the company of market hunting, soon decimated the deer population as well. From my perspective, the same process—a marked increase in prey relative to predators—led to a diminished role of cryptophytes as staples simply because there was enough to eat at the time. In other words, there was little or no need to expend the efforts required to dig roots that then had to be baked for two days before they were edible. The process in play here is akin to territorial “extensification” (i.e., larger home ranges for fewer people), which re-opens the doors to subsisting on readily visible, easily processed animals and plant foods that, for once-packed populations of hunter-gatherers, would have been the cream of the land. Extensification contrasts markedly with “intensification” wherein population packing compels hunter-gatherers to dig more and cook longer to maintain their standards of living. Following the French incursion, Spanish expeditions regularly traversed the South Texas brush country, the Post Oak Savannah, and the Pineywoods as they endeavored to provision and inspect the Crown´s presidios and missions. While their chroniclers do not attest to cryptophytes being seasonal staples, they do note that root foods were still eaten. For example, Caddo Indians taught several Spanish soldiers and a priest how to dig and cook roots when they were compelled by floodwater to extend their stay just east of the Navasota River in 1717-1718. Other chroniclers, over the next 100 years, reported Indians of the Post Oak Savannah and adjacent regions using ground nuts, tasty sweet potatoes, a grayish flour made from pond lily roots, and tuqui, a root that that resembled cassava, or manioc. Ancient Foodways TodaySome of the ancient foodways of geographic Coahuiltecans have persisted throughout the 19th and 20th centuries and to the present. My own version of participant-observation attests that heirloom Coahuiltecan prickly-pear foodways are once again widespread across the South Texas landscape. From time to time, I see "Hispanic" families along the roadside and sometimes in pastures gathering tunas or nopalitas, depending on the season. Supermarkets throughout greater South Texas sell tunas and nopalitas and restaurants serve nopalita breakfast tacos seasonally. The legacies of Coahuiltecan cookery are reported by the press as well, as evidenced by an article in the “Food & Life” section of the Austin American-Statesman on June 15, 2005, entitled “The Roots of Barbacoa” and with the lead-in: “The tradition of slow-cooking meat—beef, goat, pork, or sheep—in a pit dates back to early Mexican Indian tribes.” My first encounter with people who trace their ancestry to geographic Coahuiltecans came in the early 1990s when representatives of Tap-Pilam-Coahuiltecan Nation visited our excavations at the Richard Beene site. As an internet search on “Tap-Pilam” reveals, this resurgent group has received considerable recognition in the past several decades from a variety of non-profit organizations, the city of San Antonio, the State of Texas, the Catholic Church, Smithsonian Institution, the Texas Department of Public Safety, and various other organizations as well as the media. The National Park Service recently funded a report entitled Reassessing Cultural Extinction: Change and Survival at Mission San Juan Capistrano, Texas. It traced geographic Coahuiltecans from the heartland of South Texas to Spanish colonial missions and attested to their descendants' presence today in rural communities in South Texas and northeastern Mexico and as parishioners in San Antonio´s Catholic churches. The story that emerged was one of cultural metamorphosis, from aboriginal geographic Coahuiltecan, to ladino Coahuiltecan, to cryptic (i.e., unrecognized) Coahuiltecan to resurgent Coahuiltecan. Tap-Pilam-Coahuiltecan Nation and their non-profit organization, American Indians in Texas at Spanish Colonial Missions, are integral components of the Land Heritage Foundation, which is the grassroots organization dedicated to developing the Land Heritage Institute of the Americas. For them, land surrounding the Richard Beene site is significant as a heartland for their cultural and spiritual heritage. In recent years, it has become tradition for Tap-Pilam members to open the Institute´s annual Family Day celebration with a drum ceremony and a prayer. Tap-Pilam´s members include individuals knowledgeable about indigenous cookery and university students studying various aspects of Coahuiltecan lifeways, including their languages. They tell of cooking agave and digging wild onions with their grandparents. Plans are underway for renewed rounds of cooperative cooking with these resurgent Coahuiltecans, graduate students from the Department of Anthropology at Texas A&M University, and me. Once again people with diverse heritages, from regional to inter-continental, are coming together in search of the ancient roots of South Texas lifeways. |

|