Cairns Deconstructed

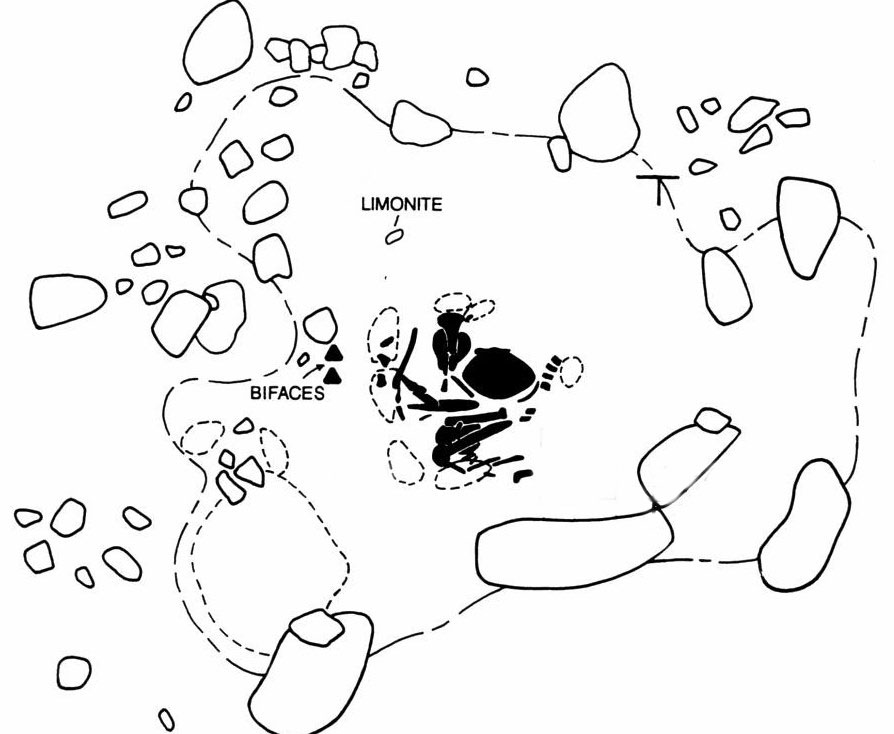

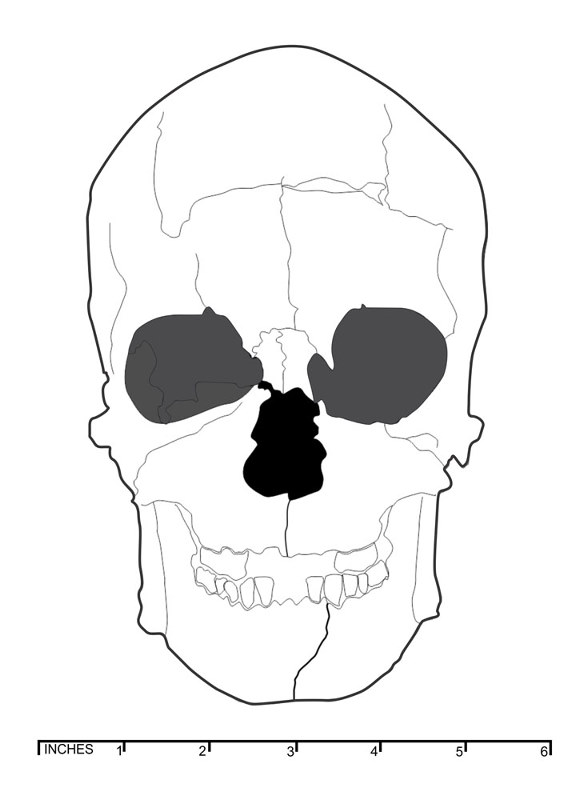

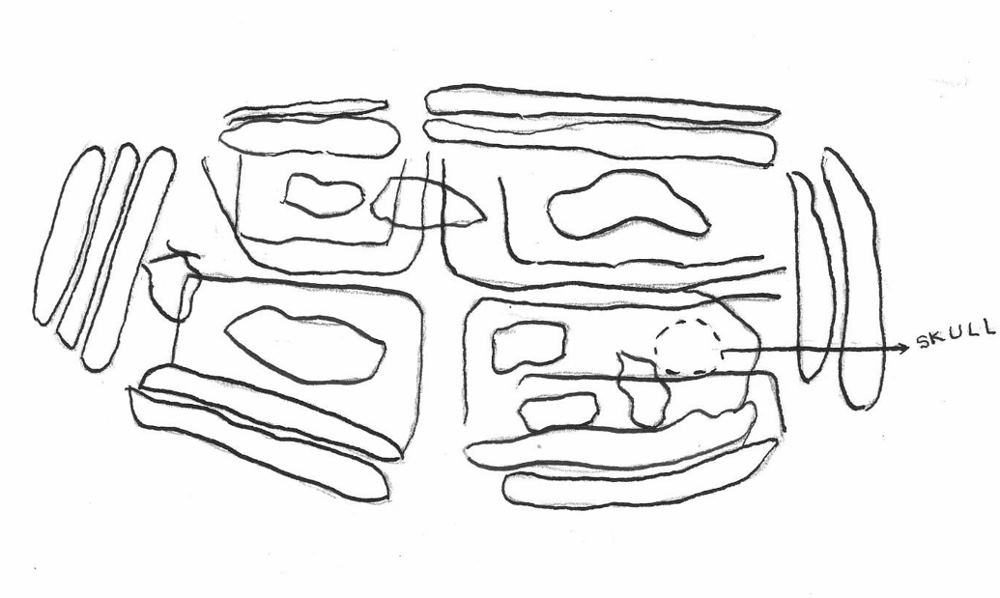

Architecture of a stone cairn grave at a Taylor County site. In this structure, one of numerous variants in the region, vertical slabs in double rows encircle the burial pit, shown in plan view at left, and in cross section at right. Note upright slabs encircling the top of the burial pit, and stones mounded over the top and sides. See Site 41TA32 in the Explore the Sites section for additional images and details. Graphic adapted from drawing by E. B. Sayles, TARL Archives. |

|

|

|

Cairn-covered cist at Shackelford County site 41SF1, shown in photo and plan drawing by A. M. Woolsey. The burial contained the semi-flexed remains of an adult female, covered with with four flat rocks described by Woolsey as having been laid in a slanted position, forming a low "gable or triangle" over the skeleton. TARL Archives. |

|

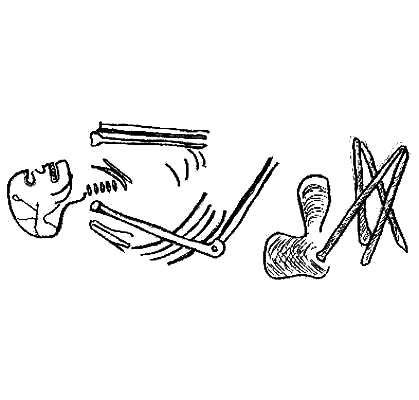

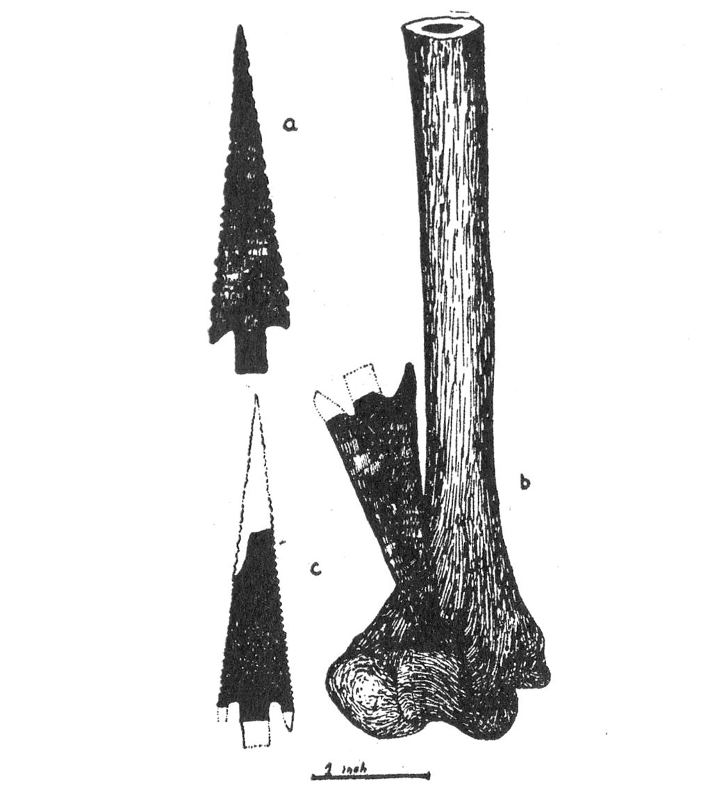

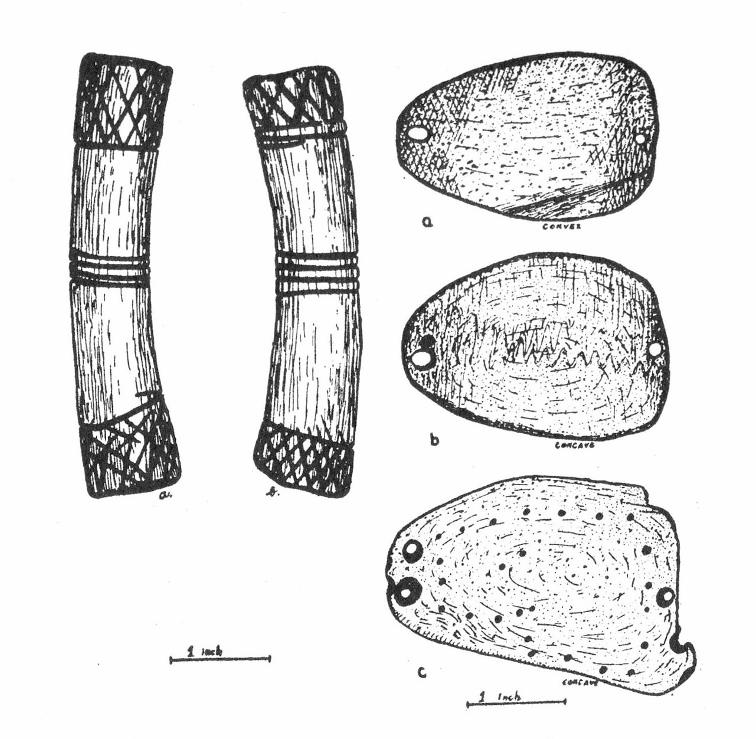

IntermentTypes and Mortuary TraditionsAlthough certain patterns are evident in stone cairn architecture, there is considerable diversity in the burials themselves. From one grave to another, even within the same cairn structure, there appears to be no clear pattern in how the bodies were prepared, how the remains were positioned within the grave, and what, if any, offerings were included. In some cases, these differences may derive from how and where the individuals died. Among primary, or "flesh" burials, signified by largely articulated remains, the most typical arrangement was flexed and semi-flexed position, in which the body was placed on its side or back with legs drawn up. In a few cases, the bodies were placed in a seated position, with backs resting against the wall of the burial pit. There appears to be no consistent pattern in the orientation of the body or direction in which the heads faced. Secondary burials contained remains likely brought from another location, after flesh was no longer present. Often termed bundle burials, these interments consisted of disarticulated bones in a pile or cluster, sometimes with the skull placed on top. Missing elements are common in such burials. Cremation and partial cremation of bodies also were a traditional practice in cairn burials. Like bundled burials, cremations may indicate that death occurred elsewhere; the body was burned and ashes collected for burial. In several unusual cases, the body was still articulated and only partially burned. Multiple interments within a single cairn were common, including burials of adults, juveniles, and infants. In several cases, the flexed remains of children were buried atop adults. One unusual burial contained the flexed remains of an adult male placed on top of another flexed male, oriented in the opposite direction. A surprising number of seemingly complete, articulated skeletons were found to lack mandibles, skulls, and other body parts. There appears to be no clear pattern of burial type based on age or sex. There were cremations and bundle burials of females and children as well as males, as well as flexed burials which cross-cut these categories. Nor did burial practices within the same cairn conform to a particular pattern, but often included a variety of burial types. For example, Site 41J73 held bundle burials, cremations, and flexed burials, along with grave offerings. It is possible these remains were placed in the cairn on different occasions. Evidence of ConflictEvidence of violent death and the apparent taking of body parts, possibly as symbolic war "trophies," was apparent in a number of burials. The most clear-cut evidence comes from the remains of two adult males within a Shackleford County cairn burial (41SF18). One had a Moran arrow point still embedded in the upper arm bone; the other had a Moran arrow point above the top of his thigh, suggesting he had been shot in the back. The right hand was missing from one the men, and there were cut marks visible on the forearm, suggesting it may have been intentionally removed. The charred mandible of a child was found in the chest area of one of the men, perhaps having been worn as a pendant or war trophy. Violent death also was evident in remains buried in several cemeteries along the Clear Fork. An adult female apparently had been shot by a serrated-blade arrow and her mandible, or jawbone, removed from her skull. At 41JS31, mandibles were missing from five of the 10 skeletons in one cairn, and at another Jones County site (41JS1), the headless body of an individual had been interred in a slab-lined pit along with numerous arrow points. At site 41JS73, several skulls were buried without other body parts, some skeletons lacked skulls, and mandibles were missing on some. Long, serrated arrow points found in one of the burials appear to be Moran points. At a Taylor County site, two individuals, their remains partially charred, were buried along with several burned arrow points, suggesting the points were within the bodies, rather than laid into the grave as offerings. At site 41CC237, remains of an adult showed signs of possible partial dismemberment. The prevalence of bundle burials within cairns also may be interpreted as evidence of conflict. Such burials indicate death occurred elsewhere, possibly away from the “home” territory. In such cases, bodies (or body parts) may have been allowed to deflesh then the bones were gathered up into baskets or wrapped in hides and brought to a sacred place for burial. There are, however, other circumstances in which individuals may have died away from the home camp, including natural causes. At a Coke County site near Lake Spence, an eroded burial held the remains of an individual with five broken arrow points in the body cavity of the lower back. The two most complete points are side-notched and triangular in shape, with serration and notching on blade margins. According to investigating archeologist Michael Collins, they resemble multiple notched points such as types Harrell and Washita common on the southern plains. At the Harrell typesite in Young County, in the northeastern corner of the region, several burials in a large, probable Late Prehistoric cemetery contained Scallorn points. Grave Offerings and InclusionsComparatively few cairn burials with offerings or grave inclusions have been reported. Such items offer a rare, albeit very limited, look at the artistic traditions and tool-making technologies of the cairn makers, as well as mortuary practices. From the reported sample of cairns, grave inclusions were found within burials of both males and females of varying ages, including children. Freshwater mussel shells are the most common items, although some may be camp debris mixed within the burial fill. More rarely, ornamental objects such as pendants, gorgets, and beads crafted from marine shell (conch columella, Olivella), snail shell, mussel shell, animal bone, and polished stone were found within cairn graves. Tools such as projectile points, triangular chipped-stone knives, bifaces, and bone implements have been recovered from a number of burials but only in small quantities. A broken tablet of incised or scratched paint stone hints at a burial ritual involving mineral paint, a common practice evidenced in prehistoric burials in other regions. In several burials, caches of offerings, perhaps originally contained within pouches, were placed with individuals. At 41JS31, a cache of bone and chipped-stone tools was buried with a woman. In a Shackleford County cemetery (41SF18), two young men were buried with tight clusters of grave offerings placed under their skulls. One cache was a set of seven deer bone tools. The other offering contained freshwater mussel shells, deer bone tools, and a charred, headless snake skeleton. Arrow points were found in a number of burials. In most cases, it is unclear whether the weapons were laid into the grave as offerings (likely still in their shafts) or if they were the cause of death. Regardless, they are particularly important in establishing a cultural chronology for the stone cairn mortuary tradition. The points found within west-central Texas cairns consistently were described as thin and exceptionally well made. Most had serrated blade edges, and a few had small notches. Moran type arrow points were found within burials in at least five sites (41TA60, 41CN187, 42SF18, 41JS31, and 41JS1), and a Scallorn-like point also was found in the 41JS1 burial. Chadbourne arrow points were found at sites 41TA32, and at 41TA60. That both Moran and Chadbourne points were found at the latter site suggests they were used contemporaneously. At site 41CN94, a Sabinal arrowpoint was found within the burial pit, and two Perdiz-like arrow points made on blades were recovered in sediments above the burial. A dart point resembling type Darl was found in a complex cairn burial at 41TA32, and its significance is unclear. It may have been collected as a special item from an earlier time, and laid in the burial. Alternatively, it may indicate that the cairn tradition began earlier in the latter or transitional part of the Late Archaic. The single reported radiocarbon date—A.D. 425 +/- 145 from an adult male at site 41CC237—is from the Late Archaic to Late Prehistoric I transitional period and would seem to support this. Skeletal AnalysesAlthough only a small portion of the total skeletal remains from cairn burials has been analyzed, several physical characteristics have been noted by researchers. A number of the skeletons apparently possessed dolichocephalic, or extremely long and narrow, skulls. In his various articles about skeletons from the cairns, Cyrus Ray commented repeatedly on this striking feature, as well as heavy brow ridges in some of the crania. Curved femurs and side-flattened tibia also were noted in the post-cranial remains. Other than dental caries, relatively few signs of disease were reported in the skeletons. At site 41JS73, however, an adult male exhibited extensive bone disease in the form of exotoses (bony outgrowths) on his left femur, and the head of the bone was described as “deformed, much mushroomed, and eroded.” In 1933, Ray sent two of the skulls from cairn burials to physical anthropologist Ernest Hooton at the Peabody Museum at Harvard University for further examination. Although he was extraordinarily concerned at the time with classifying races based on skeletal morphology, Hooton echoed Ray's observations about the unusual cranial characteristics, and noted that "they are not very close to what seems to be the central type of the Basket-maker, being narrower, longer, and lower." By "Basket Maker," Hooton was referring to late prehistoric peoples of the American Southwest. For whatever these early analyses are worth, they highlight features that could be important markers in comparing cemetery populations to identify prehistoric communities and how they interacted with one another. The human remains constitute an important resource for understanding the human condition during a critical time in Texas prehistory. The great majority remain unstudied, and only a fraction have been analyzed using modern techniques for forensic study, dating and chemical analyses.

|

|