Investigations and the Search for Cultural Patterns

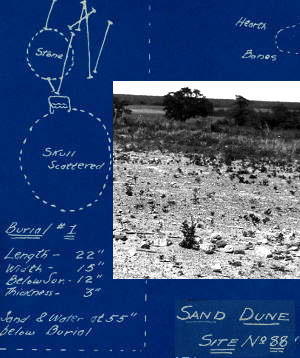

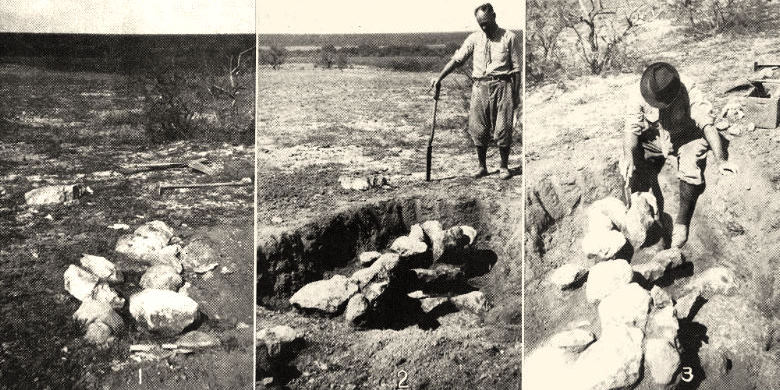

Excavation of burial number 3 at the Myatt site, Jones County: No. 1,Top layer of stones with earth removed; No. 2, Middle layer of stones, earth removed; No. 3, another view of middle layer of stones. Below this layer, interred within a small circular pit about four feet below surface, were the closely flexed remains of a small adolescent, and within the skull was a single finger bone. In Ray's scenario, the body had been placed in the pit, then covered over with a stone structure, on top of which was placed "a great mass of heavy stones covering a large area in the center of the grave... ." Image from 1937 TASP article, “More Evidence Concerning Abilene Man,” by Cyrus Ray (Plate 34). |

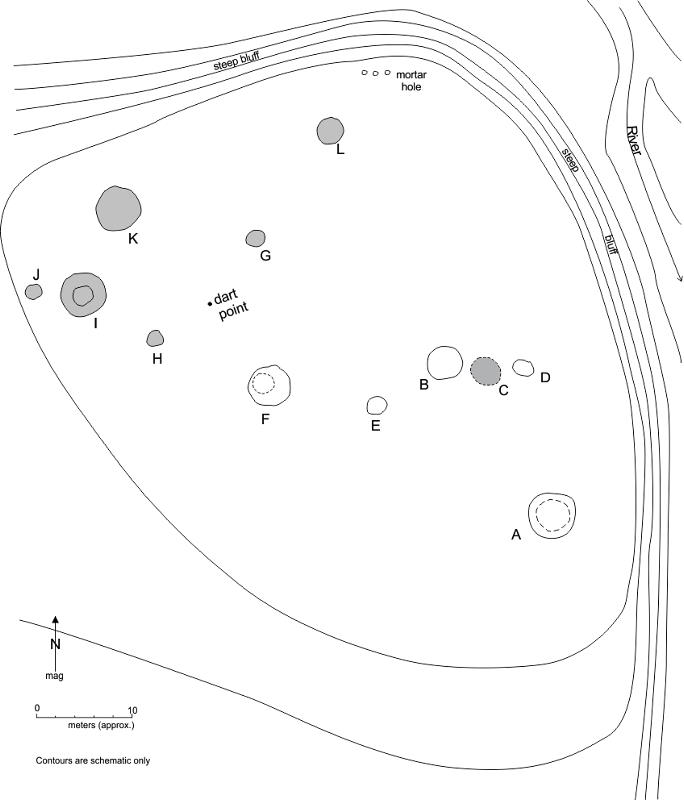

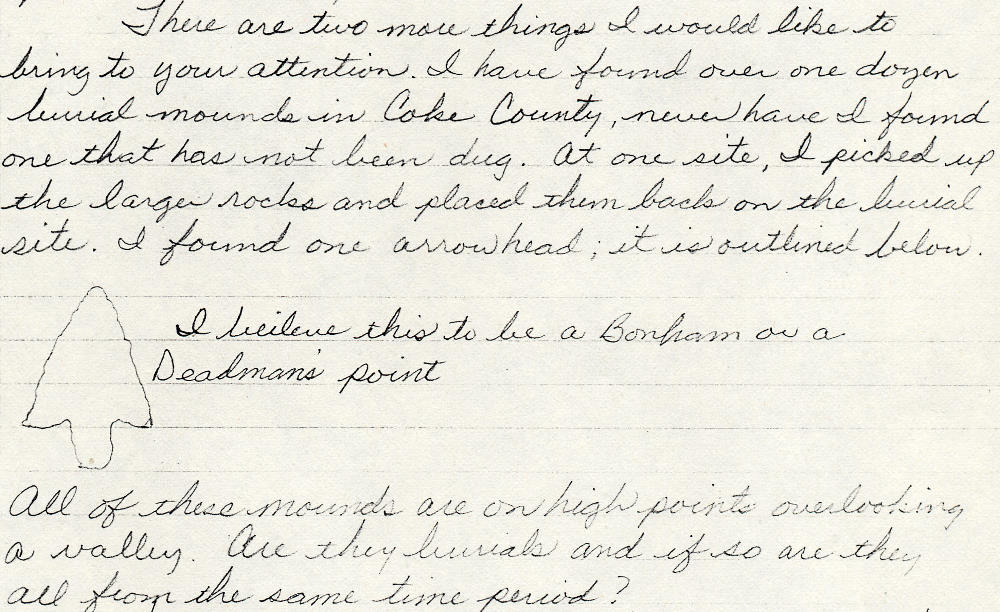

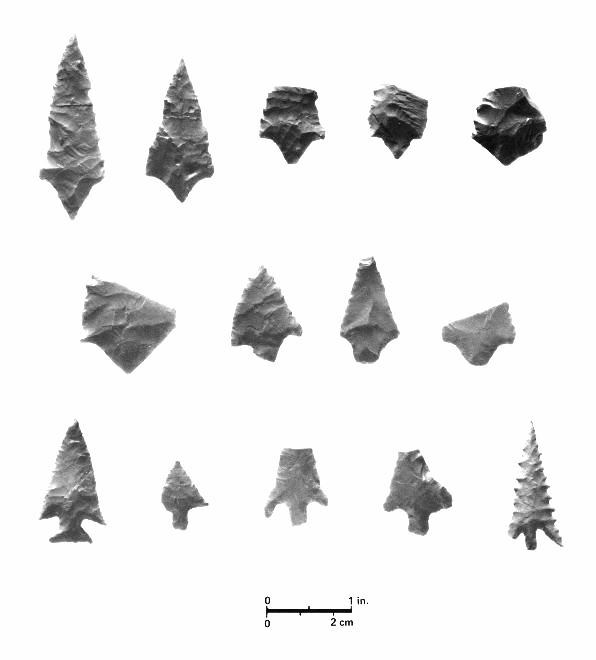

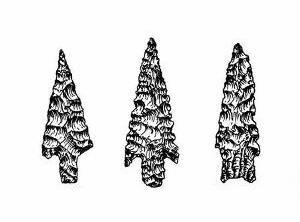

Later InvestigationsFrom 1936 to 1941, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) designated funds for archeological excavations in Texas, resulting in a spate of more-systematic work in the Abilene area. As part of the Texas Technical College WPA archeological project, archeologist Joe Ben Wheat excavated numerous cairn burials in the Abilene area as well as a rare, stratified campsite, the Myatt site. Information from this site may have some bearing on the age of the cairn burial culture. Two of the distinctive arrow point types found in cairn burials were found in an occupational layer with a Late Archaic, Ensor-like dart point, and this stratum lay above one containing Zephyr-like dart points of the transitional Archaic period. These and other excavations are described only in unpublished WPA quarterly reports. Some of Wheat's most significant work was conducted along an escarpment overlooking the Clear Fork, in some of the same areas investigated earlier by Ray. Distributed within a roughly two-mile area, sites 41JS1, 41JS73, 41JS122 constitute a series of cemeteries harboring the remains of at least 27 individuals. Based on the treatment of the bodies, including removal of skulls in some and mandibles in others, a number of people met a violent death. Stemmed arrow points with serrated blades were found within some of the graves. Further details on these and other sites can be found in the Explore the Sites section. Additional archeological investigations in the region were carried out by University of Texas archeologists A. M. Woolsey and A. T. Jackson, largely responding to queries from area ranchers. Woolsey conducted excavations at two McCulloch County cairn sites which included both flexed and cremated remains (see Explore the Sites: 41MK26) and in Shackleford County (see 41SF1). Jackson worked alongside Ray in some excavations, and in a 1941 TASP bulletin article described a rock-covered burial on the tip of a narrow high ridge in Coke County in which the remains of three individuals were found along with two stone pendants and a conch shell gorget. One of the most thorough and well-documented excavations of cairn burials was conducted by avocational archeologist Robert Forrester of Fort Worth at site 41SF18 in Shackleford County in the late 1930s. Situated on a terrace of the Salt Prong of the Brazos, the site contained the remains of 18 individuals, including two young men who presumably died of arrow wounds. Stemmed arrow points with serrated edges were found in the graves—including one point still embedded in bone—as well as an array of ornaments and other grave offerings. Beginning in the 1950s, large-scale archeological surveys were conducted in the region prior to construction of reservoirs on the Colorado River, including O.H. Ivie (formerly known as Stacey Reservoir), Robert Lee, and Oak Creek. Covering thousands of acres, these surveys identified numerous prehistoric and historic period sites. Because of the sensitivity of buried human remains, concerted effort was made to identify cairn features, including a literature review for previously identified sites which might lie in the proposed reservoir basin. Results of these efforts illustrate the challenge of cairn investigations. At O. H. Ivie, for example, archeologists determined that the great majority of cairn sites had been disturbed, if not destroyed by relic collectors, and thus were ineligible for further investigation. Others lay outside the reservoir boundaries. Of 38 cairn sites previously reported, 29 were revisited by survey teams, and testing or full excavation was conducted on 18. Most were determined to be the foundations of historic structures or stacked stone markers denoting property boundaries. Only six of the stone features identified as cairns contained (or apparently once contained) prehistoric burials, and of these, only two, 41CN94 and 41CC237, contained intact burials. See Explore the Sites for more detail on these excavations. Survey to the SouthArcheologist and San Angelo native Darrell Creel has studied cairn sites for a number of years, conducting independent survey of private ranch land in Irion, Tom Green, Schleicher, Coke, Runnells, Nolan, and Concho counties as well as researching the records and collections of Sayles, Ray, and other investigators. His documentation of cairn sites provides information about distribution and patterning in the southern portion of the west-central Texas region, particularly along tributaries of the Colorado River, including the Middle Concho. During survey, he observed multiple, contiguous rock features—often numbering over 100— along bluffs and rocky slopes on both sides of minor draws. Many appeared to be in groups, with combinations of both very large (ca. 8 meters in diameter) and smaller features (ca. 4 meters). The most extensive clusters typically were situated along the tops of ridges. Like those in the Brazos watershed, many cairn sites in the Colorado watershed were located near outcroppings of high-quality nodule chert which clearly had been utilized, based on abundance of tested cobbles and roughed-out bifaces. At some sites, multiple circular and oval mortar holes had been worked into limestone ledges along nearby bluffs. The sheer number and variety of cairn sites made documentation difficult. As Creel observed in his1980 field notes, “Some of the features which have been recorded as cairns may be natural, while some other small rock piles not recorded as cairns may be cultural. It simply is difficult to tell in some cases.” Excavations at two of the cairns provided no answers. No clear internal structure could be detected nor was there evidence of cultural material, a situation perhaps analogous to the "blank," or empty, cairns encountered by Joe Ben Wheat during his excavations at 41JS122. As Creel noted, "Other than the symmetrical form and apparently non-natural accumulation of large slabs and small pebbles, there was no evidence for this being man-made." Nonetheless, based on landowners’ accounts of human bone dug from cairn sites along the Middle Concho and the presence of burned bone still on the surface, many of the cairns are—or once were—graves. Yet, their meaning is perplexing. As Creel asked in his notes, “…how does one explain the occurrence of an estimated 150-200 [at least] burials so widely dispersed in an average small, west Texas draw? Is this draw typical or is it a special place? The possibilities are many, and—if these are graves—very intriguing.” Refining Frameworks: The Blowout Mountain PhaseMany insights have come from systematizing the records and collections of earlier researchers. Building on the earlier cultural designations by Sayles, Ray, and others, Creel proposed a new cultural framework to encompass specific cultural remains—including some of the cairn burials—dating to the early part of the Late Prehistoric period in the west-central Texas region. Termed the Blow Out Mountain phase, this designation pertains to the later part of the time period encompassed in Sayles’ and Ray’s Brazos River Culture designation. Classifications such as these, while often overlapping and confusing, are important frameworks for ordering diverse information and constructing cultural histories. A phase refers to a pattern of archeological remains—a cultural expression—delimited both chronologically and spatially. Said differently it refers to distinctive sets of artifacts and features relating to a particular time period and within a reasonably well bounded area. Frequently, there may be multiple phases encompassed within a larger period. From a human behavioral standpoint, Texas archeologists refer to the Late Prehistoric period to mark two important changes in prehistoric technology: the introduction of the bow and arrow and the use of pottery. This period is typically broken into Late Prehistoric I (ca. A.D. 800-1200) and Late Prehistoric II (ca. A. D. 1100-1550). The Blow Out Mountain phase represents a transitional, localized pattern dating to the time of the introduction of the bow and arrow in the region until the beginning of the Toyah phase of Late Prehistoric II. As we learn more about this cultural expression, the Blow Out Mountain phase may well be separable into shorter chronological intervals. The specifics of the Blow Out Mountain phase were set forth in Creel’s 1990 report on a prehistoric campsite in Tom Green County (41TG91), one of the few deeply stratified sites excavated in west-central Texas. With layered deposits preserving evidence of repeated prehistoric occupations marked by time-diagnostic artifacts, such sites serve as critical reference points in establishing regional cultural histories. In the case of 41TG91, cultural materials were contained within 14 strata representing at least the last 2600 years, from Late Archaic to Historic Period times. Notable artifacts and features of the Blow Out Mountain phase include distinctive arrow point types, stone-lined hearths, flexed, cremated, or bundled burials in stone cists, and large quantities of mussel shell in campsites. Arrowpoints include two little-known stemmed types, Moran and Chadbourne, which appear to be limited almost exclusively to the west-central Texas region. Moran points typically are exceptionally well made, with straight, often serrated blade edges, and long stems with straight to convex bases. The Chadbourne type is a triangular point with small shoulders and wide expanding stem with straight to concave base. Both types have been found in cairn burials. Scallorn-like arrow points with characteristic expanding stems also have been found in burials along with Moran points. Large, well-made triangular bifaces also are characteristic of the Blow-Out Mountain phase. Notably lacking however, are the ceramics, end-scrapers, beveled knives and bison bones that are so numerous in the later Toyah phase sites. Based on faunal remains from 41TG91, occupants of the site during this time consumed deer, prairie dog, jackrabbit, cottontail, turtle, fish, river mussel, and other animals. While site 41TG91 did not contain evidence of a cairn burial, skeletal remains (teeth and cranial fragments) of perhaps two individuals were found within disturbed contexts attributed largely to the Blow Out Mountain phase. Portions of the cranial materials had been charred, suggesting partial cremation. This unusual practice of burning only a portion of the corpse has been recognized frequently in cairn burials. Clearly there is much more to be learned about cairn burials and the people who made them. We can form a very tentative picture of their lifeway based on evidence from the Blow Out Mountain component at 41TG91 which contained the same types of serrated, stemmed arrow points found in some cairn burials. To date, the area in which cairn burial features (and associated artifacts) have been most heavily reported is a 14-county area in west-central Texas apparently dating to the Late Prehistoric I period, but possibly beginning earlier. The limits of this cultural expression, both temporal and spatial, are still being defined. |

|