Ceremonial Cave stands out as one of the most

unusual and interesting sites ever found in Texas, but its

story is surely one of the most tragic examples of archeological

site destruction in the state. On seeing the cave in the late

1920s, area resident Eileen Alves lamented: "Treasure

hunters of the most malignant and energetic type have reduced

the interior to a state of chaos." Fortunately, Alves

and her husband Burrow Alves purchased some of the looters'

collection, saving it from dispersal and ultimate destruction,

for it is only as a group that the objects begin to convey

their full significance. And fortunately, their alert to the

archeological community prompted an investigation of the site

before it was destroyed.

In 1928, the Alves invited archeologists C.B.

and H.S. Cosgrove to explore the site. At that time many museums

across the country were conducting fieldwork with the intent

of adding to their collection exhibits. Representing Harvard's

Peabody Museum, the Cosgroves were working nearby in the Mimbres

area of southwestern New Mexico, exploring Pueblo ruins and

what they believed to be the cultural remains of the earlier

Basketmaker culture. The dry caves of the Hueco Mountains

presented the possibility of finding perishable materials

of similar cultural affiliation-basketry, clothing, and other

items not commonly preserved in unsheltered sites.

The report of explorations by C.B. Cosgrove

published in 1947 provides us the bulk of the limited documentation

that exists of the deposits at Ceremonial Cave. Because the

deposits were already severely disturbed at the time of their

investigations, it is likely we will never have a better understanding

of the cave than what they observed. From their exploration,

we learn of the remarkable objects found in the cave, but

we also puzzle along with Cosgrove at the combination of certain

artifacts and what their significance might be. There is an

astonishing and diverse group of objects that are probably

offerings, along with hundreds of fiber sandals, some embedded

with cactus thorns. There was a puzzling layer of grass on

the floor of the cave. There were the skeletons of a woman

and a child, carefully placed in a cave niche. And throughout

the cave deposits, in the same chamber containing ceremonial

offerings, were quantities of desiccated human excrement.

Cosgroves' 1928 map of the cave shows the main

chamber as well as drifts, or extensions, as they appeared

at the time, and denotes the area near the mouth of the cave

where a great many ceremonial objects were found. Unfortunately,

there is little documentation of the ceremonial deposit, although

Cosgrove specifically mentions prayer sticks or ceremonial

staffs (yucca stalks with attached fiber bolls), darts, and

so-called hair ornaments. Given the nature of the early looting,

it is likely that the ornaments and tablitas and certain other

items purchased by the Alves were from the ceremonial deposits

as well. Although a number of dart shafts were found in the

rear portion of the main chamber, it is possible those were

carried to the back by rodents; indeed, several shafts show

signs of gnawing

In addition to the remarkable array of artifacts,

the Cosgroves found the skeletal remains of two individuals,

a young child about 2 ½-years old, and a young woman.

Although their bones had been scattered by animals, it was

evident that the woman had been placed in a bay on the side

of the cave, her legs drawn up, and head facing south. She

had been adorned with jewelry-—a shell pendant and a

necklace of seeds-—but there were chipped stone projectile

points within her body as well, one in her pelvic cavity and

another on the right side of her body. Whether these attest

to her violent death—or were placed there for some other,

more-peaceful reason—is not known. We do know, however,

that at her death she was carefully wrapped in a blanket of

rabbit skin strips. Cosgrove believed the blanket was an early

type, associated with the so-called Basketmaker culture.

Cosgrove's interpretation of the cave deposits

and the placement of artifacts is important. He notes the

absence of fire pits or ash strata that would indicate it

might have been used as a dwelling or that might indicate

it was occupied for an extended period of time. One enigmatic

feature—a layer of packed grass lying directly on the

cave floor and burned to ash in some places—indicates

a stay of some sort. Cosgrove believed it was bedding for

transient visitors, and its burned state an indication that

it was carelessly fired.

Another curious finding was an enormous quantity

of desiccated human excrement, or coprolites, throughout the

cave. Unfortunately Cosgrove and subsequent investigators

failed to collect any of the coprolites, which could have

provided valuable information on the diet of the cave visitors

as well as age of the deposits.

In his report, Cosgrove sums up his interpretations:

"A shrine it appears to be, with a suggested curious

custom of the purging of the bowels and leaving of worn-out

sandals when the objects were deposited there as offerings."

However, some investigators today hold a different interpretation:

that is, both the coprolites and the large numbers of sandals

may be attributable to earlier occupations at the site. Given

that almost all of the cave was dug up, the large quantities

of these items are more likely a function of large-scale sampling.

Several other investigators visited and, in

some cases, conducted excavations at Ceremonial Cave, adding

a number of artifacts to the collections and raising additional questions about the deposits. Among these was E.B. Sayles, who in 1931 visited

the cave and conducted limited testing in the rear of the

main chamber. He reported what he termed a "grass mat"

as well as a concentration of charcoal and ashes, yucca-leaf

sandals, cordage, bone awls, and the bone of an extinct antelope

dating to the late Pleistocene. (Bones of other extinct animals

were also found by the Cosgroves and probably reflect use

of the cave by Pleistocene animals.)

Today, Ceremonial Cave is encompassed within

the bounds of Fort Bliss. When archeologists from The University

of Texas at El Paso surveyed the area and its caves for the

United States Army Air Defense Artillery Center in 1997, they

noted that there was almost nothing left in the cave. For a more detailed summary of investigations at Ceremonial

Cave, download a pdf

version of the report prepared in conjunction

with the UTEP Survey report.

|

|

Treasure hunters of the most malignant and energetic

type have reduced the interior to a state of chaos.

Eileen Alves, 1931. |

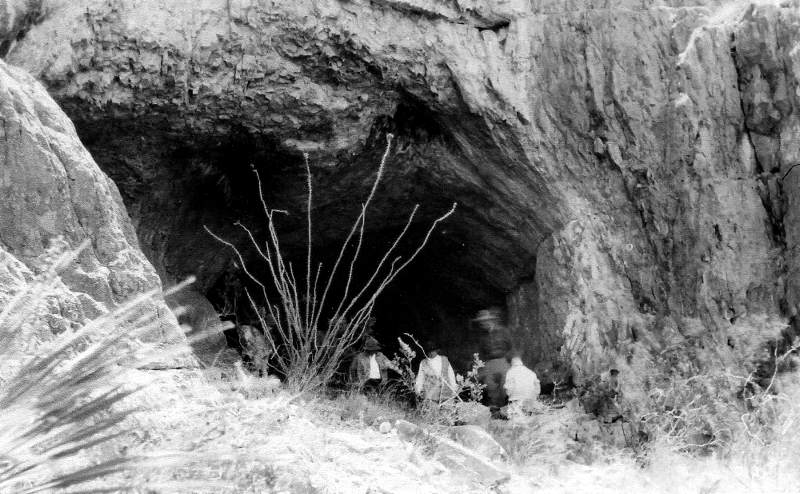

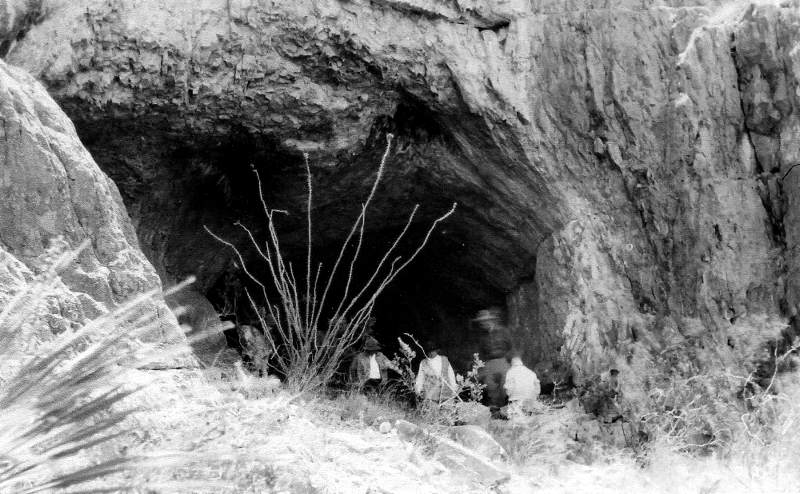

Excavations in progress at what is thought to be Ceremonial Cave. Photo by Jim Alexander, courtesy of Richard D. Worthington and El Paso County Historical Society.

|

Plan map of Ceremonial Cave and Caves

1-3, as recorded by C. B. Cosgrove in 1928. Cosgrove

identified the faintly circled area (d) in Ceremonial

Cave as "area of large ceremonial deposit."

The small chamber marked as "c"denotes the

area of an adult burial. Map from Cosgrove 1947.  |

Closeup of dart or stalk pajo, or

prayer stick, reported by C.B. Cosgrove from Ceremonial

Cave, circa 1928 (enlarge for full image). The atlatl

darts are shown with attached fiber bolls which were

filled with tobacco. The pajos were made of sotol bloom

stalks. The specimen at left is roughly 20 inches

long; the originals would have been much longer. Image

from Cosgrove 1947. Enlarge to see more examples.  |

A mother-of-pearl ornament, its shell

material derived from the Pacific Coast hundreds of

miles away, was likely a prized trade object. Based on its similarity to rock art depictions at nearby Hueco Tanks and other sites, it may have been a mask, possibly a miniature version. TARL Collections. Photo by Milton Bell.  |

One of the hundreds of "scuffer toe" sandals found

in Ceremonial Cave. Their numbers prompted Cosgrove

to suggest that they were the shoes of the pilgrims

themselves. TARL Collections. Photo by Milton Bell.  |

|