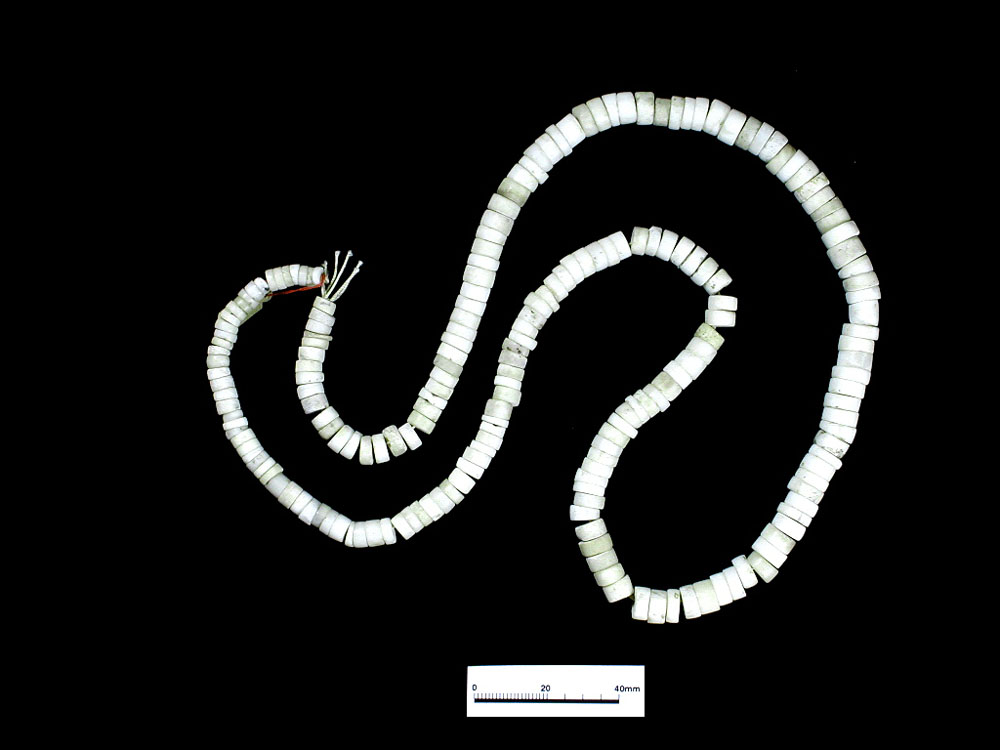

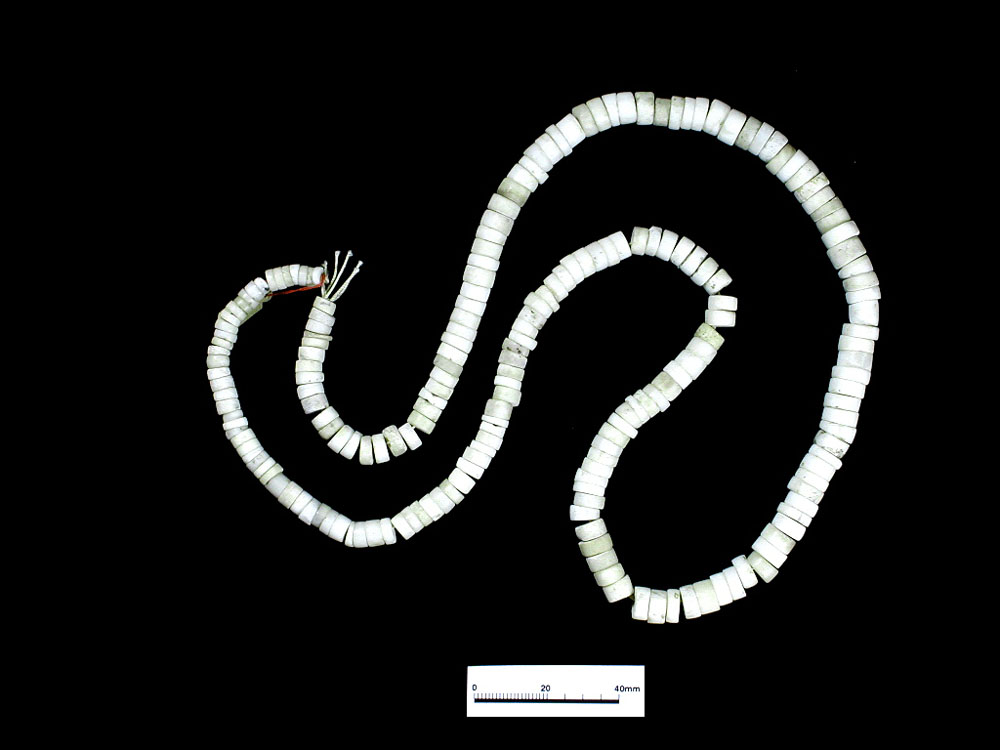

Tiny shell beads of Olivella—a Pacific

coast marine snail—were strung into necklaces or used

as ornaments on clothing. TARL collections  . |

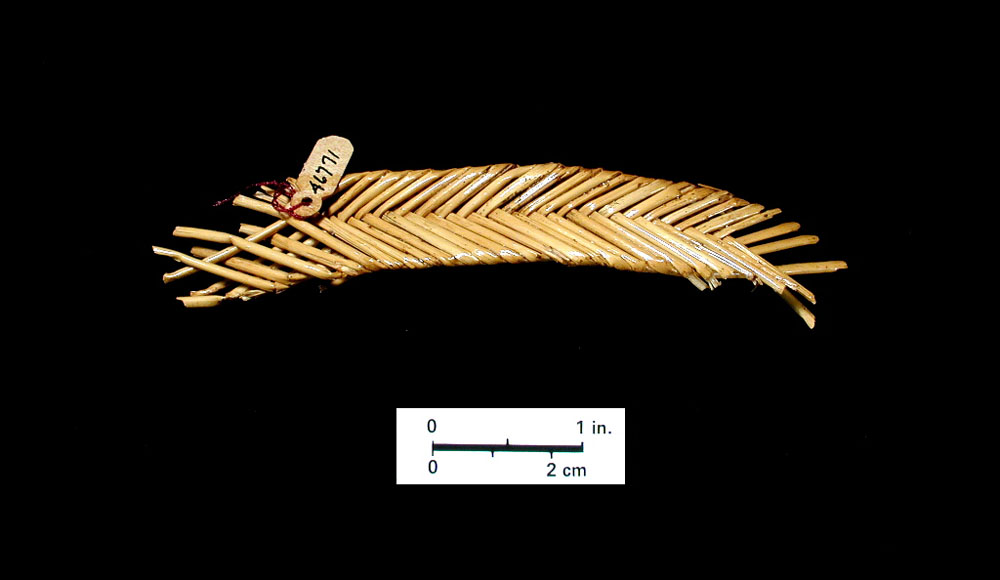

Sandals of yucca fiber were found by the hundreds

in the cave. To Cosgrove, their incredible numbers suggested

they were left by pilgrims bringing offerings. Most if not all of the sandals at the site were of the "scuffer toe" variety, which cover only the ball of the foot and were primarily for running. TARL collections  . |

Unique in the southwest, this finely crafted turquoise armband was likely

placed at the cave as an offering  . |

Cut-shell necklaces or bracelets were found in quantity. TARL collections.  |

An unusual necklace made of cut sections of fossil crinoid, a marine invertebrate  . |

Bracelet or armband cut from the shell of Glycymeris,

a marine mollusc of the Pacific/Baja coast.  |

Necklaces such as these were made of shell cut with a chipped stone burin

or other sharp-edged tool. TARL collections.  |

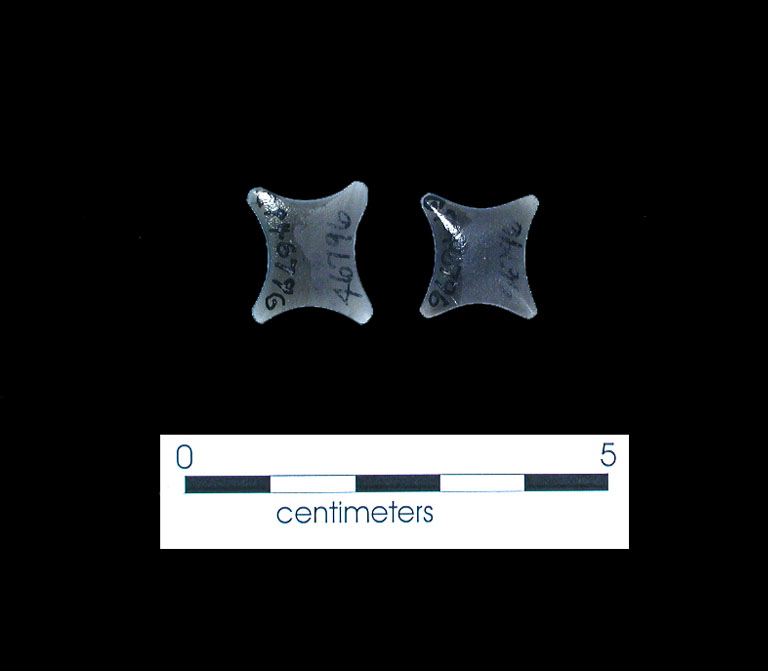

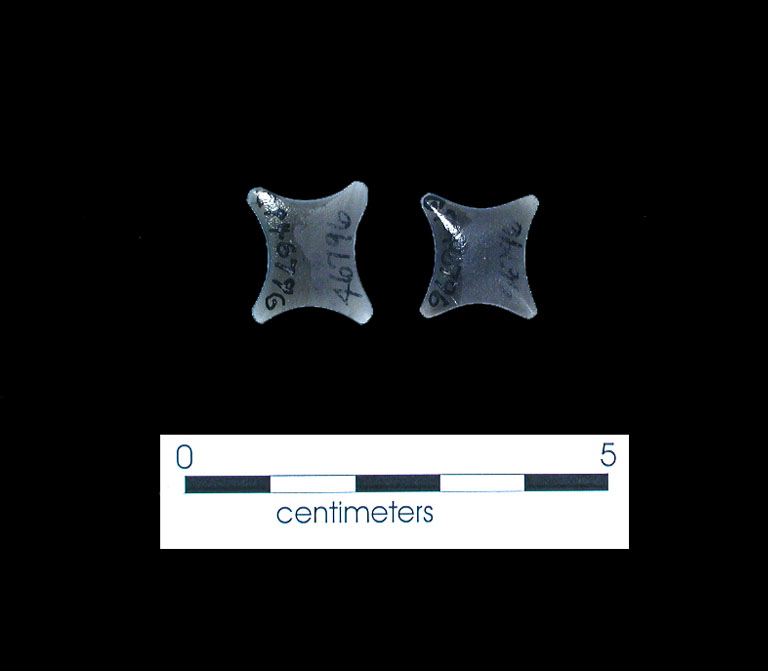

Exotic black glass, or obsidian, was flaked

and then polished in the shape of cruciforms. Another example

of these curious objects was found in a room at Firecracker

Pueblo dating to about A. D. 1450. Four-pointed stars, thought to symbolize Venus twins, are abundantly featured in petroglyphs and rock paintings in the late Pueblo period.  |

Tubular beads made of shell of the vermetid snail, a marine gastropod about the diameter of a pencil. These shells likely came via Casas Grandes in Chihuahua. TARL collections.  |

"Apron" of twined fiber cording was typically worn tied around the waist by women.  |

Cactus barbs embedded in the sole of this

sandal may attest to treks through spiny underbrush—or

may simply be the work of packrats who brought hundreds of

barbs into the cave. TARL collections.  |

The base of a coiled basket of yucca fibers. TARL collections.  |

A yucca- or sotol-cane "fire-hearth" with drill holes for fire-starting.

A small piece of cane or wood would have been rapidly twisted in one of the holes causing intense friction and gradual buildup of heat.

Once a spark was emitted, it would be caught in a wad of tinder such as dried grass, brought to flame,

and with added kindling and fuel, a fire would be made.  |

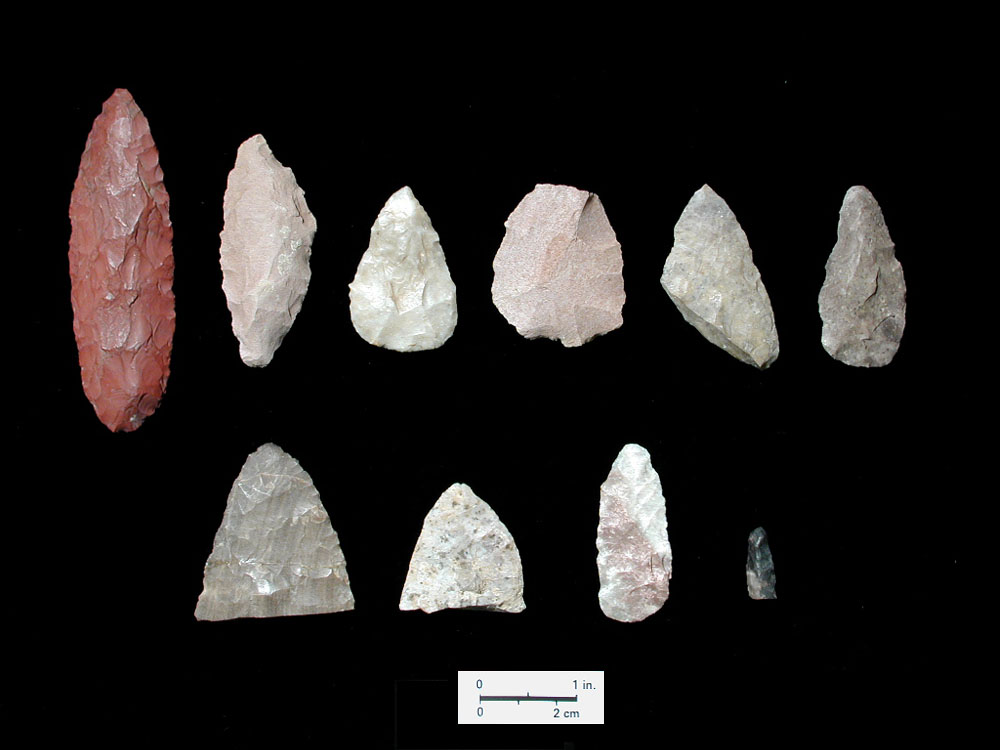

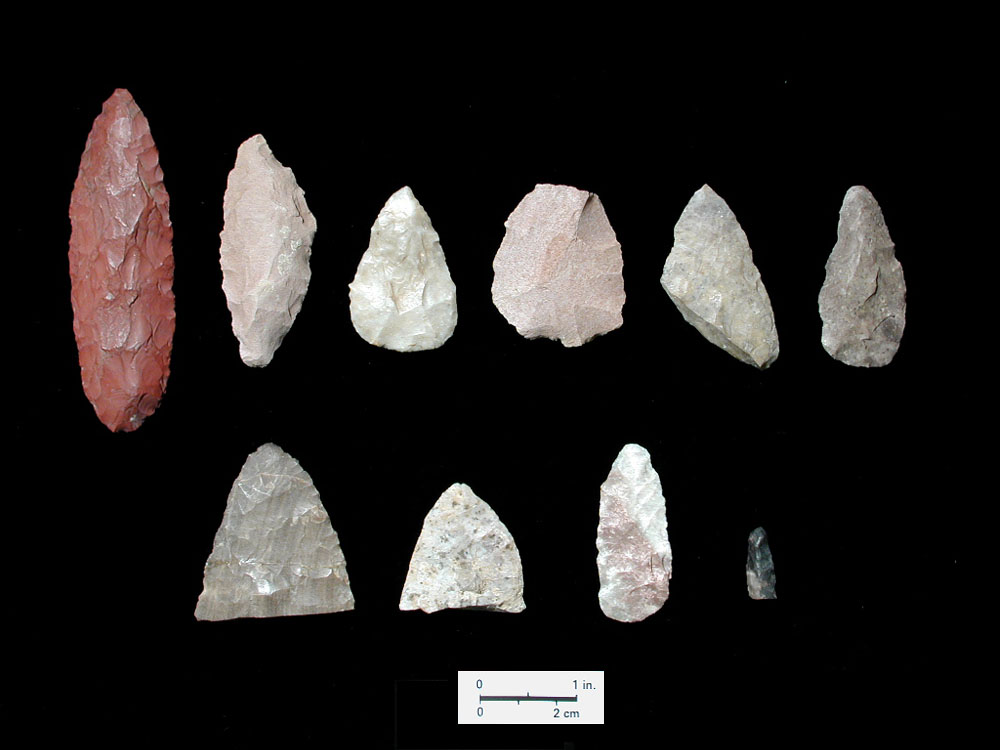

Examples of chipped-stone tools. The dart and arrow points found in the cave are

of types that can be correlated to archeologically identified

culture periods spanning thousands of years. TARL collections. Enlarge for additional specimens.  |

A remnant of a once-elaborate cape

or robe, this section of cording at one time was entwined

with feathers or bits of fur. The complete specimen—yards

of twine holding long turkey feathers or perhaps lengths

of rabbit pelt—would have been a warm outer garment

or perhaps was fit for a shaman's ceremonial attire. TARL collections.  |

Intricate knots in the cording of the cape,

as shown in this close-up view, would have held feathers or

fur. Traces of downy fuzz are still barely visible within

several of the tightly knotted loops. TARL collections.  |

Wooden bunts. These would have been hafted

to the end of a weapon to stun an animal, rather than kill

it. TARL collections.  |

|

Sacred Offerings amid the Refuse

It is not clear—and indeed, will never

be so—which items were placed in Ceremonial Cave as offerings

and which were merely the remains of daily life left behind

by much earlier visitors to the cave. The agents of destruction—rodents

and human collectors—displaced artifacts from their original

context and damaged others, making it difficult today to interpret

their function and meaning. But we can make informed guesses

about the ceremonial objects, based on their rarity and similarity

with objects from other shrine caves.

Among the artifacts of Ceremonial Cave are a

finely crafted bracelet and pendants of semi-exotic (nonlocal)

stone and ornaments of shell from coastal areas hundreds of

miles away. There are also seemingly less rare objects whose placement,

quantity, and completeness suggests that they were left there

as offerings: spears with stone dart tips, curved hardwood

"rabbit sticks," and woven items. The fact that

several spears are complete and that some are adorned with

unusual fiber bolls containing tobacco also suggests these were

intended not for hunting but as a special offerings. In many Puebloan groups, darts and "prayer sticks," have particular symbolic significance, carried in rituals by leaders and offered in quantity to spirits for protection and power.

In striking contrast to the finely crafted and jeweled objects in the cave were dozens and dozens of heavily worn fiber sandals. Their quantities were so large, in fact, that early investigator C.B.

Cosgrove was moved to interpret them as the shoes of the pilgrims

themselves, perhaps placed there along with their offerings

as part of a ceremonial ritual. Some archeologists today are

reluctant to accept this interpretation, compelling though

it may be. Most if not all of the sandals—and many of

the other fiber objects, ranging from quids (chewed pieces

of fiber) to yucca mats and cord aprons—may have been the clothing

and day-to-day trappings of various earlier occupants of the

cave.

Today we can view the rare ornaments and offerings

left in ritual ceremony by prehistoric peoples along with

what may or may not be merely rubbish, and we can continue

to speculate as to the line of distinction. Lacking provenience

information and documentation for most of the artifacts, the

only other line of evidence still available is the age of

the objects. Radiocarbon dating could help determine when

the various artifacts were deposited, but no comprehensive

dating of these artifacts has been undertaken. Dating of the hafted darts is the first step in this program, and results have shown them to relate to early use of the cave by Late Archaic residents of the area who may or may not have become the people referred to as the Jornada Mogollon.

Who Were the Ceremonialists?

What can be said of the people behind the

objects, the ceremonialists themselves—probably many

generations of them—who came to the cave to leave their

diverse offerings? Who were they and what was the meaning

of their journey? Based on the cave's location and the similarity

of the artifacts to other cultures of the Southwest, Ceremonial

Cave was used early on by Late Archaic hunting and gathering peoples and later by peoples of the Jornada-Mogollon culture from about A.D.700 to 1450, close to the time of the arrival of the Spanish in the Southwest. These later people lived first in small pithouse hamlets and later in pueblo communities, raising small crops of corn and beans, but also still practicing the earlier ways of hunting and gathering.

Near the caves of the Huecos is

the site of Hot Well Pueblo, one of the largest in the area,

and farther west, at El Paso, is Firecracker

Pueblo, occupied for a brief period around A.D. 1450. At the nearby site of Hueco Tanks, somewhat earlier villagers (ca. A.D. 1075-1150) lived in subterranean pithouses, practicing small-scale farming. Water, trapped in the deep tanks, or huecos, drew people to the remarkable place. Based on the abundance of rock art there —miniature masks and dancers, distinctive feathered serpent and stepped-cloud altars— Hueco Tanks was not only an oasis in the desert but a place of spiritual significance for Jornada-Mogollon and other peoples.

The Puebloan system of cosmology is complex,

its ceremonies and rituals still shrouded in secrecy. But

there is a special meaning attached to caves and crevices

in the earth: these areas penetrate the underworld, or the

Below, where the Pueblo supernaturals live. Leaving offerings

is a way of more closely approaching these mystical regions.

As explained by southwestern archeologists Florence Hawley

Ellis and Laurens Hammack, the supernaturals are "neither

all good nor all bad, but they require offerings and persuasion

to carry on their part of creativity and regulation of the

universe."

Specific objects, including turquoise, white

shell, abalone shell, and red stones have great meaning within

the Pueblo legends and are correlated with the various supernaturals,

Sun and White Shell Woman, in particular. Specific sites—caves

and lakes—are revered by Pueblos as the sipapu, or opening

to the underworld; others are sunshrines, or both. During

winter and summer solstice, offerings are placed in shrines,

and prayers are offered.

Among the Pueblos, bows for winter offerings are painted red, a color applied to bows or arrows in summer only for purposes of witchcraft. In terms of Ceremonial Cave, many of the spears and foreshafts are painted red, suggesting that they, too, may have been winter offerings for success in hunting. Similarly, some of the yucca stalks with attached fiber bolls are also painted red, as are the more recent tablitas.

In addition to the red paint, these items also may have been adorned with exotic ornaments. Ellis and Hammack note that among some of the Pueblos, “a bead should be tied to the backs of bows, the ‘bead’ on one offered by Hunt Chief being a pendant of abalone shell like those worn by images of the War gods.” Whether any of the shell beads or the abalone pendants from Ceremonial Cave were attached to spears or prayer sticks is unknown, but some of the pendants still have cordage in the suspension holes and some of the beads are still strung on cordage.

Puebloan peoples are highly secretive

about the nature of their rituals, even keeping them from

other native peoples not connected to the ceremonies. Some

observances involved long treks or pilgrimages, possibly of

several weeks' duration, and with stops to place offerings

at more than one shrine. For the ceremonialists at Acoma Pueblo,

New Mexico, before 1900, this included stops at Chaco Canyon

and Chimney Rock in what we know today as the Four Corners

area. While we cannot say with certainty that similar beliefs

and circumstances held sway at Ceremonial Cave, the similarity

in artifacts is striking.

If the range and quantity of the objects

is any measure, Ceremonial Cave has no equal in its part

of the Southwest. It was, perhaps for many centuries, a

shrine of great importance. The astonishing numbers of sandals,

darts—both complete and broken—snares, pipes,

prayer sticks, throwing or fending sticks, basketry, and

other items clearly distinguish this collection from others

known in the region. Although precious few of the artifacts

have provenience information, much can still be learned

through a comprehensive analysis of the collections that

now reside in at least seven museum and research laboratories.

With the exception of the seven darts described in the Hafted Dart Point Analysis section, none of the materials have been radiocarbon dated. Until many more such analyses are conducted, the story of Ceremonial Cave, as best as it can be reconstructed, will remain untold.

The artifacts shown here are housed at TARL

and derive from collections by A.M. Woolsey (1936 investigation

by UT Austin); E.B. Sayles and the Gila Pueblo Survey (which

includes the original collection purchased by Eileen and Burrow

Alves); and Tom O'Laughlin who recovered surface objects at

the cave over a period of several decades. Other artifacts

and records from Ceremonial Cave are curated in at least six

other institutions or archeological laboratories, including

the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution,

and the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard

University.

A child-sized sandal of yucca fiber appears

still serviceable.

A woven strip of yucca fibers may have

been part of a tumpline, or headband loop used when carrying

heavy loads.

Pointed bone awls, with cordage still attached

to one, were used in basket making and sewing (click for full

image). TARL collections.  Small pointed twigs, wrapped with cording,

were thought by some investigators to be hair ornaments. One

such twig bundle, however, was found attached to a spear (now

housed in the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian

Institution) and perhaps was intended for symbolic purpose. A more practical interpretation, based on ethnographic accounts, is use as a tool for spearing fruits on cholla cactus plants. TARL collections.

Closeup view of hafted ends of darts. The

chipped stone points were typically inserted in a grooved

slot in the tip of a shaft, secured with a glue-like mastic,

and then wrapped in cordage or animal tendon. TARL collections. See Hafted Dart Analysis section for radiocarbon dating and CT scans.

|

Pendant beads of exotic shell likely were acquired from

the far-trading Puebloan peoples of the northwest or the

Hohokam to the west.

TARL collections  .

Click images or camera icons to enlarge

|

Painted "tablita" constructed of wood slats joined by cording. In some Puebloan groups, tablitas were worn as headdresses or masks by dancers. The red color has significance in hunting rituals or may be related to witchcraft in some groups. Photo by Laura Nightengale. TARL Collections  . |

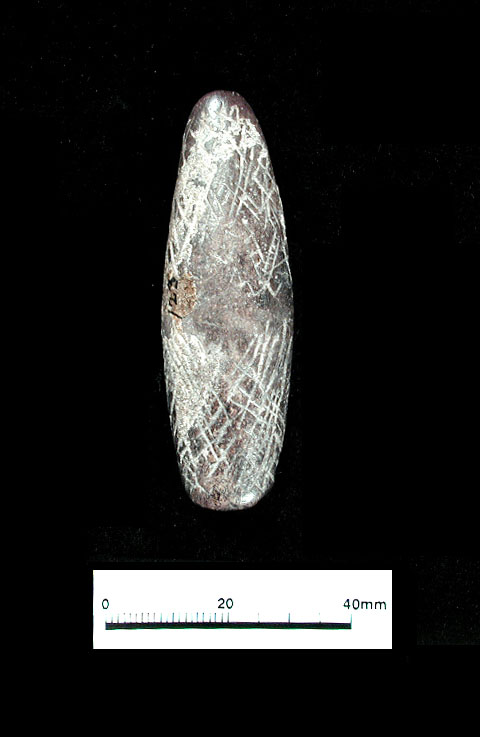

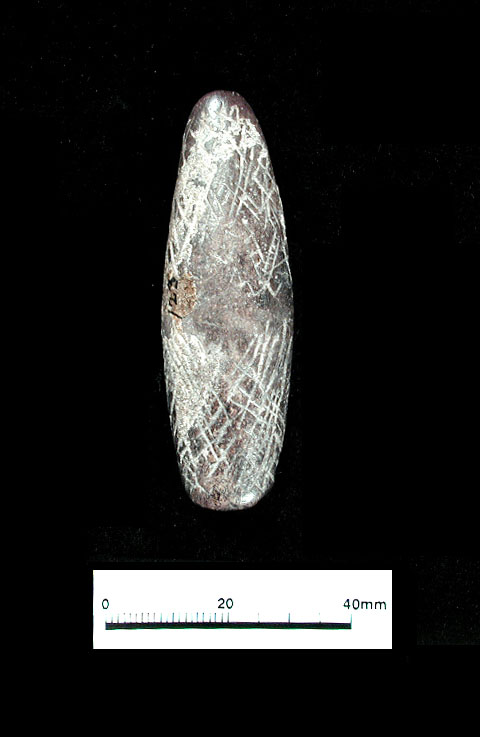

This elaborately incised stone object, may have been used as an atlatl

weight, adding

stability and distance to the throw. TARL collections.  |

Abalone from the Pacific and other shells were cut into

shape and drilled with stone awls to make pendants such

as these (enlarge for full image). TARL collections.  |

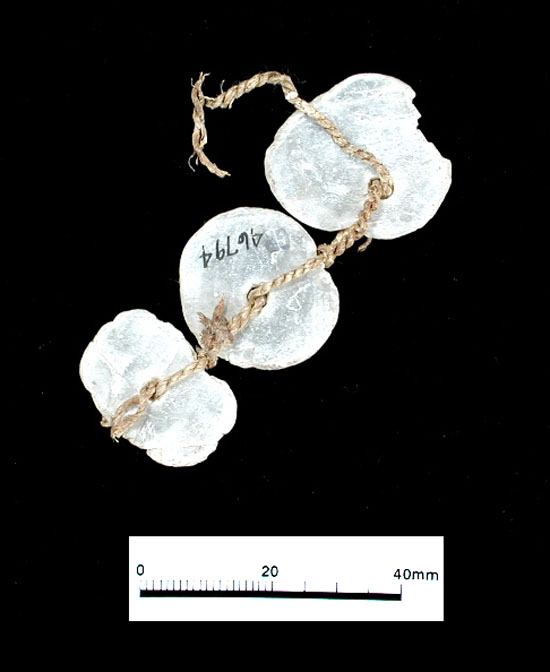

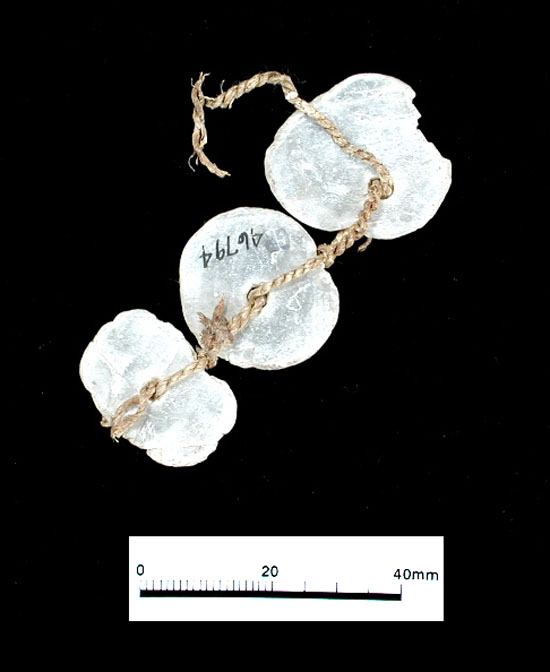

Ultra-thin discs of gypsum were perforated and suspended

on fine yucca fiber cords as necklaces or other ornaments. TARL collections.  |

Opalescent mother-of-pearl from Pacific coast abalone shells

has been cut into squares to form a mosaic pattern in this

ornament, which may have been used as a ritual mask, or perhaps in miniature. Enlarge to learn more. TARL collections.  |

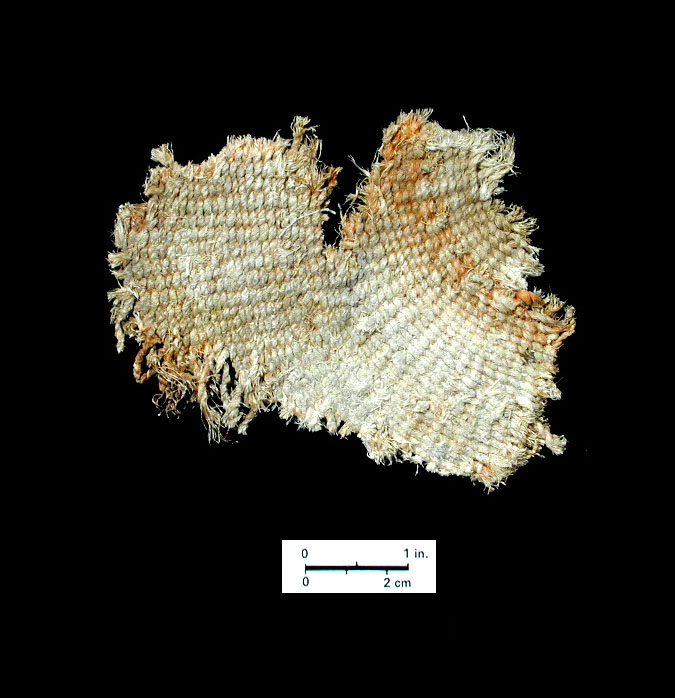

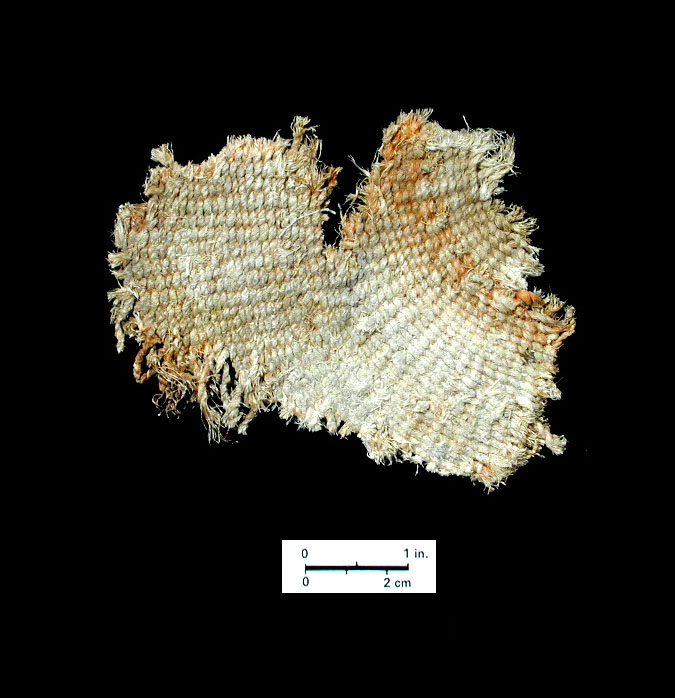

A scrap of tightly twined fiber fabric was perhaps part of a bag or pouch,

a secure container for carrying small objects. TARL collections.  |

Quids, or chewed wads of sotol or agave, are commonly found

in dry caves and shelters. They are the remains of a meal

similar to artichoke leaves. After cooking, the leaf bases

were scraped through the teeth to obtain the sugary flesh;

the fibrous leaves were discarded. TARL collections.

|

Chipped stone tools (enlarge for full image).

The specimens in the center of the top row are dart

points, the third one made of quartz crystal. The other objects

are tools chiefly used for hide scraping, cutting, and other

butchering tasks. TARL collections.  |

A small bundle of grass stalks, perhaps used as matting or bedliner. TARL collections.

|

Curved wood throwing

and fending sticks. Enlarge to learn more. TARL collections.  |

Closeup of wrapped yucca stalks and spear

shafts. The specimens are

wrapped in plant fiber strips, perhaps used to attach fiber

bolls, or pouches, containing tobacco. A complete spear with

such an attachment, found in Ceremonial Cave, is now in the

National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution. Enlarge for full image.  |

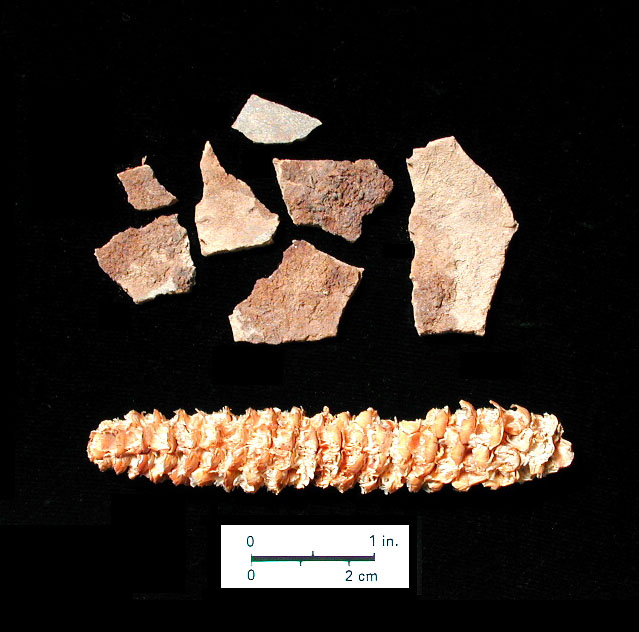

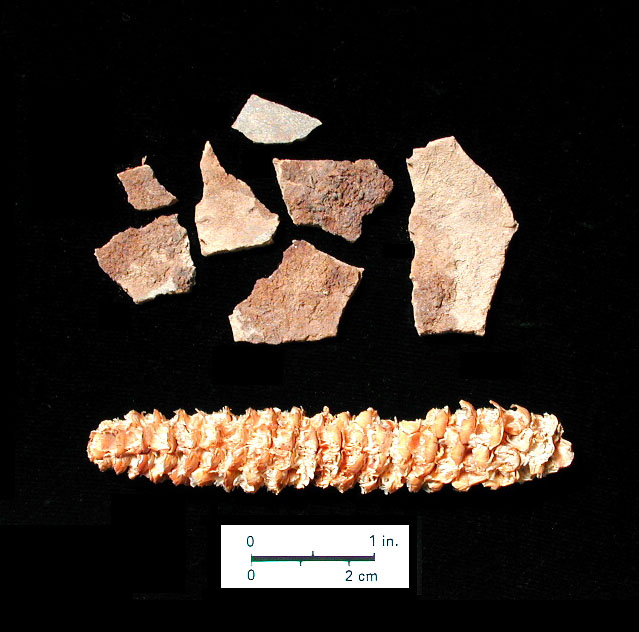

A corn cob and fragments of gourd may have been left as

an offering, or were merely remains of a meal left by earlier

occupants.

|

Pajo "prayer stick," or atlatl dart made of yucca bloom stalk with plant fiber wrapping and pajo bundle. The sticks, with the attached bundles often filled with tobacco or other special materials, were used in ceremonies and placed as offerings in shrines and other sacred places. Photo by Laura Nightengale. TARL Collections.  |

|