Reinterpreting Mission History: The 2nd Location of Espiritu Santo at "Tonkawa Bank"

|

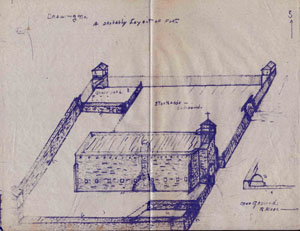

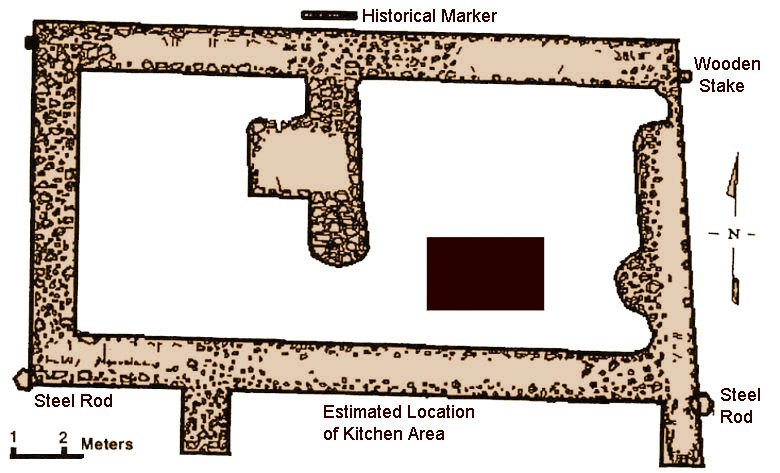

| Scaled drawing of building foundations at second location of Mission Espiritu Santo (41VT10), based on excavations in 1996-1997 in the Victoria city park. Originally thought to have been merely a temporary "visita," the site was verified as a functioning mission through historical research and archeological field work by members of the Texas Archeological Society. Drawing from Hindes et al. 1999. |

|

For many years, historians, archeologists, and others have believed that Mission Espiritu Santo was moved from its coastal location on Garcitas Creek to a site in present day Mission Valley. In recent years, this scenario has been revised, opening another chapter in the mission's long and complicated history. What has long been known as the Tonkawa Bank Site (41VT10), located in the city park in Victoria, Texas, has been reinterpreted to be, in fact, the second location of Mission Espíritu Santo de Zuñiga. The site had previously been recognized as a visita, or temporary location, of the mission. Historians and archeologists do not yet know exactly when the mission was moved to that site, but it was at its new location by April 1, 1726. Based on historical accounts, the move had been a rather hasty one, made even before the friars had received official permission. Further, the move apparently was made independently of Presidio de la Bahia and the protection that it offered. Harsh environmental conditions and the hostility of the local Karankawas made the Garcitas Creek site near Matagorda Bay highly undesirable to the missionaries who struggled daily to survive in the difficult setting. By March, 1724, Father Baena (or Bahena), one of the priests at the first mission site, had written to the Governor of Texas: Your Lordship may well believe that I can hardly wait to see you here at this Presidio and Mission...so that you may listen to me at your feet, take pity on me and on this unhappy Mission, and reform whatever is worthy of reform. By the spring of 1725, Fray Agustín Patron was the only surviving original missionary at the Garcitas Creek location. Afflicted with a "horrible disease of running sores," he was eager to find a more suitable location. He also wanted to find more receptive neophytes than the Cocos, Curacames, and Cujames (Karankawa). Patron had already started to recruit the Jaranama (Aranama) Indians and in fact had constructed an acequia near a new mission location. Because of the great numbers of Aranama Indians, two mission sites were selected. One, the Mission Valley location (41VT11) was at a large creek on the new road to the Rio Grande. The Tonkawa Bank site was occupied contemporaneously with the Mission Valley site, and it continued in use at least until about the time that the larger Mission Valley mission and the presidio were moved to the San Antonio River at current Goliad, Texas, in 1749. The contemporaneous occupation of the two locations-Tonkawa Bank (41VT10) and Mission Valley (41VT11)-has contributed to modern disagreement about the historical significance and priority of the Tonkawa Bank site. Noted historian Charles Ramsdell wrote that the mission had been moved more than three times, a statement suggesting that Tonkawa Bank was the site of a more formal mission than a visita. Father Marion Habig, Catholic priest and Spanish colonial historian, believed the second location of the mission "could not possibly have been the Mission Valley site," but rather, was near Bloomington, or "near (or in) Victoria". In 1967-68, John Jarratt, an avocational archaeologist and historian, identified the Tonkawa Bank site as the "Second site of Mission Señora del Espíritu Santos de Zuñiga." Jarratt also identified the Mission Valley site as the "third location." Nonetheless, site 41VT10 was not recognized as the mission's second location by many historians and authors of 20th-century publications on the mission and its presidio. As its name suggests, the Tonkawa Bank site was a Tonkawa Indian settlement when Martín de León founded Victoria in 1824. John Linn, who settled in Victoria in 1829, noted, "The Toncahuas were located at or near Victoria, their field being above the site of the present town. They had a church, which was erected on what is now known as 'the Toncahua Bank,'the foundation of which is still visible, as it was built of masonry." Only remnant of the tribe was left as of the early-mid 19th century. Archeological InvestigationsThe Tonkawa Bank site was first excavated by Jarratt in 1922 when he discovered flint flakes, shell, animal bone and human remains at the location. Other investigations occurred at the site through the years: additional work done by Jarratt in 1930-31, and 1965-1966; Dr. Frank M. Setzler of the Smithsonian in 1931; J.E. Pearce of the University of Texas at Austin in 1932; A.M. Woolsey of the University of Texas in Austin in 1932; Archeological Steward E.H. Schmiedlin in 1978; CAR-UTSA in 1978 and in 1989 (in the area directly to the east of the colonial site); Kay Hindes, Smitty Schmeidlin, and Ann Fox in 1996; and most recently by the Texas Archeological Society Field Schools in 1997 and 1998 under the direction of Dr. Tom Hester, TARL, UT, Austin. The archeological investigations and archival research have provided extensive information regarding the mission complex. The site contains the remains of stone ruins and other features dating to the Spanish colonial period, and shares many of the basic characteristics of other Spanish missions. It is located on a high bluff above the Guadalupe River near a Spanish Colonial crossing, close to indigenous resources such as stone and wood that could be utilized for building construction, and near Native American encampments. Mission components defined at site 41VT10 include the stone and cobble footings of a two-room rectangular structure (the probable church), rubble or cobble alignments representing walls or enclosures, postholes that probably represent a wooden stockade wall, evidence of jacals in the form of postholes and daub, a possible compound gate, a plaza area, and a cemetery. A tremendous amount of modification activities have taken place over the last 270 years, including the dynamiting of the stone ruins ,but the fact that these features have been identified suggests that there are probably more architectural features present. Much of what we know about the site is based on 20th-century eyewitness accounts and from the archeological excavations. Jarratt maintained that the walls had been standing three feet high as late as 1922. He found a two-room stone building partially surrounded by a stone wall on the north, east, and south. Des Hiller, who as a boy played around the old foundations, remembered that the large door to the building faced west or toward the river and the walls were about 5 feet high in places. The walls "had a lot of windows or what could of been windows; they were very small and looked more like slots left in the wall for some reason." Another resident of Victoria reported that the ruins at this site "looked like those at the old Quincy Davidson Place." The Quincy Davidson place can be identified as 41VT11, the Mission Valley site. The stone ruins measured 40 feet on the north side, 42 feet on the south side and 25 feet in width. The west end on the south side had an extension of two feet. The main door was located in the west elevation. The building was divided into two rooms by a partition wall also two feet in width with a fire place in the front room. Buttresses were noted at each corner. Material Culture at the Second Mission SiteInformation regarding the material culture of the Native Americans and Spanish at the mission site is represented by a very small number of artifacts (most have been bulldozed and hauled away), but in most cases they are consistent with the artifactual assemblages at other 18th century Texas mission sites. Artifacts found include ceramics, metal, glass, including glass trade beads probably from rosaries, lithics including gunflints and arrowpoints, ground stone including a vesicular basalt mano fragment, animal bone, shell (including a bead made from the columella of a conch shell indicating trade between the Aranama and the coastal groups), and clay beads (clay beads were also listed in the inventory of goods acquired for the Mission Santa Cruz de San Saba in 1757). Ceramic artifacts found at this site include Goliad wares (so named for the mission's final location), unglazed sandy paste ware including one variety that appears to be wheel thrown and is not found in sites in the San Antonio area, burnished wares including a small novelty figurine produced in Tonalá, Mexico, during the 18th century, lead glazed wares, olive jar fragments, and majolicas including Puebla Polychromes, a type not found on sites in Texas after 1725, Puebla Blue on White, Abó Polychrome Type B/Aranama, and Puebla Blue on White II. Interestingly, the archival record tells us that the Aranama women "manufactured cloth, and also water jars used by themselves." According to Linn, the Tonkawa also manufactured blankets, cultivated corn and vegetables, and owned cattle and horses. It is interesting to hypothesize that these sandy paste wares that are found only in the Goliad missions can be directly associated with the Aranama. Vessel shapes represented include storage jars or containers, flat bottomed bowls, and medicinal jars. Based on the statistically significant presence of certain tin-glazed ceramic sherds, of which the largest majority is Puebla Polychrome, an initial occupation date of 1725 (or earlier) can be established for 41VT10. This date corresponds directly with the archival data, supporting 41VT10 as the second site of Mission Santo de Zuñiga. Metal artifacts include metal buttons, lead worm, and thin sheet copper fragments including a lug fragment from a repaired copper pot. The Jarratt collection at TARL also includes "a fragment of Braid made of Copper Silver and Brass thread". This fragment was found in association with burial No. 1. Looking BackWe do not yet know when—or if—the Tonkawa Bank site ceased to exist as a "formal" mission after the construction of the third, and larger, mission at the Mission Valley site (41VT11), but archival data supports a contemporary occupation. Based on archeological investigations and material culture as well as retranslations and reanalysis of primary source documents, the site appears to represent a much more substantial mission location than that of a visita or an interim location. This suite of evidence thus points to four locations of Mission Espiritu Santo de Zuniga: the first site on Garcitas Creek, the second site (41VT10) in the immediate area of present-day Victoria, the next at Mission Valley (site 41VT11), and the fourth and final site at Goliad. Because the first location of the mission at Garcitas Creek as yet has not been discovered the second site of Mission Espiritu Santo de Zuniga is the earliest known location. |

|