The gently rolling grasslands near the San Antonio River valley were a key factor in selecting the fourth, and final, site for Mission Espíritu Santo. Vast herds of cattle thrived on these mission lands.  |

The mission compound as it may have appeared in its heyday, with bright white plastered walls painted with fanciful designs. Photo of model at Mission Espíritu Santo State Historic Park, courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Ruins of the mission at the start of 1933 field work. TARL archives.  |

One of the quarries from which native laborers extracted stone to build the mission. 1933 photo, TARL archives.  |

A dapper A. T. Jackson, who conducted the first archeological investigations at Mission Espíritu Santo in 1933, is shown here in a trench at an east Texas site (41FK2). Working for the University of Texas in 1933, Jackson conducted the first excavations at Mission Espíritu Santo. TARL archives.  |

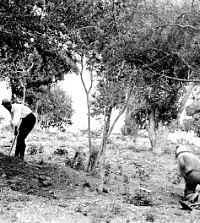

Digging gets underway in July 1933 at "Aranama Mission," as it was then called by people of the day. TARL archives.  |

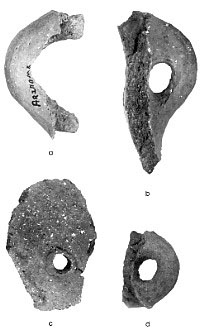

Ornate Spanish buttons and crucifixes studded with colored glass were among the items uncovered by Jackson in the mound. Likely worn by the friars, such ornaments were rare among the quantities of native-made objects, such as chipped-stone tools and crude pottery. Photo by Monica Trejo. TARL collections.  |

|

By 1749, Mission Espíritu Santo had been moved to its fourth and final location on the lower San

Antonio River as part of the colonization plan of Nuevo Santander. Situated on a natural rise, the mission compound was within the protective sights of Presidio La Bahía, which had been

established on the opposite bank of the river.

Little is known about the circumstances of the move or how the buildings were erected. As was the

case at the presidio, the earliest structures probably were temporary buildings including jacales, small huts

built of vertical poles or branches, covered in mud or plaster, and topped with thatched roofs.

Records indicate that by 1758, several buildings, including the church and priests' quarters, had been replaced with more-permanent structures

made of stone, quarried from a nearby outcropping. Native peoples apparently continued to live in jacales. Ten years later, an inspection tour inspection tour

led by Father Gaspar Jose de Solis found most of the remaining wood structures had been replaced.

In his 1768 report, he observed:

Besides the necessary offices and church buildings, the Bahia mission has dwelling-quarters for the religious, the soldiers, and the Indians, and all of these structures are respectable and sufficiently large.

In the succeeding two decades, additional alterations were made which brought the mission together more cohesively. Stone buildings housed living quarters, workshops for weaving and other crafts, storerooms, and the church. Most fronted on an interior courtyard, or plaza, where chores, such as corn grinding, could be carried out. Jacal housing for the native inhabitants was aligned inside a tall stone wall which surrounded the compound. This defensive outer structure, with bastions placed at two corners, helped protect the interior

of the mission from attack by hostile Indians such as the Lipan Apache, a continuing concern for residents on the south Texas frontier.

In 1768 Fr. Jose Francisco Lopez reported that the mission buildings were in good condition and that the Indian quarters were made of stone with flat beamed roofs covered with thatch, or straw. There is little information regarding subsequent changes to the buildings.

The overall situation at this mission was much different than that at the earlier locale. Here the operation became much more stable and self-sufficient. There were periods of prosperity. The relatively small cattle herds begun at Mission Valley grew to as many as 40,000 head in the fields near the San Antonio River valley. Introduced to Texas by Spanish expeditions, the cattle adapted well to the south Texas climate. The enormous herds were free-grazing for the most part, although periodically native vaqueros branded those that could be rounded up. The animals were slaughtered by the hundreds to provide food as well as hides and tallow, and these goods were used to trade for merchandise in San Antonio and in Mexico.

Agriculture was not a success, however, over the long run. All efforts to establish an irrigation system failed, and periodic draughts caused numerous crop failures. Frequently, the friars had to turn to the San Antonio missions for corn.

In spite of the relative prosperity of the mission, the Aranama left periodically, for months and years at a time. Disease took a toll on the native population and birth rates were insufficient to replace the numbers. Indian raiders continued their attacks and raids. Changes in Spanish law regarding unbranded cattle cost the mission thousands of its herd, resulting in seasons of hunger and increased hardship. As the mission's fortunes plummeted, there was little to hold the native peoples.

By 1790, the Spanish government was ready to unburden itself from the high cost and administrative burden of the missions. The political landscape had changed, alleviating the need for outposts and settlements on the frontier. Having succeeded in gaining Louisiana from the French, Spain no longer needed Texas to serve as a buffer and instead turned its attention to missions on the west coast.

After 109 years in operation at four different locations the mission finally was closed. An inventory made of the mission in 1830 at the time of secularization noted six rooms within the stone compound, all collapsed. Although much still stood in ruin at the time, the compound then became home to two colleges, Hillyer Female College followed by Aranama College for men. This use continued until the Civil War, when the men left to fight and the structures were used alternately by the southern and northern armies. In 1866, a hurricane dealt a final blow to the structures, and the complex fell into total ruin. Uncontrolled digging and artifact collecting occurred periodically. In 1931, the city and county of Goliad donated the site and adjacent lands for a park, and the move toward restoration of the mission began, with transfer to Texas Parks and Wildlife in 1949.

Archeology at the Mission

The first organized excavations at the Goliad County location (41GD1) were conducted in 1933 by A. T. Jackson, under the direction of James E. Pearce, chairman of the University of Texas Department of Anthropology. Carried out over the course of a month, the work was funded by the

Works Progress Administration. Jackson's investigations were not systematic by today's standards and consisted of little more than digging through a large trash heap, which he dubbed "Aranama Mound," located behind the stone perimeter fence of the mission. A trench was excavated to help delineate the stratigraphy of this deposit, but apparently only a verbal summary was made of this effort.

Aside from crude sketch maps, the only remaining record is a summary of finds and a typewritten report Jackson wrote at the conclusion of the project. Sprinkled with observations about

the project, the site, and its cultural features, the report chiefly categorizes the thousands of

artifacts recovered and is illustrated with photos and drawings.

Download Jackson report. (28,177 KB) Download Jackson report. (28,177 KB)

p. 77-127

p. 77-87 (5,083 KB) p. 77-87 (5,083 KB)

p. 88-97 (5,091 KB) p. 88-97 (5,091 KB)

p. 98-107 (5,875 KB) p. 98-107 (5,875 KB)

p. 108-117 (5,678 KB) p. 108-117 (5,678 KB)

p. 118-127 (6,434 KB) p. 118-127 (6,434 KB)

Whereas Jackson's work produced collections relevant to the material culture of the mission residents, the

next phase of operations at the mission was focused largely on discerning the layout and architectural

features of the mission. During the mid- to late 1930s, laborers from the Civilian Works Administration (CWA) and

Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), federal programs devoted to employing out-of-work Americans during the

Depression years, engaged in a multi-year effort directed by the National Park Service. The goal of this ambitious project was to

reconstruct the mission for the public.

Led by archeological foreman Roland Beard, CCC workers dug a series of

trenches throughout the interior of the compound to identify walls, footings, floors, and foundations. A large number of artifacts also were recovered. Where there were no structural remains, artifacts were used to help establish

the nature of the deposits and determine whether they pertained to the Spanish Colonial period.

Beard traced a number of important aspects in the mission’s early construction history. Significantly, his excavations uncovered post holes and evidence thought to relate to early wooden structures and a surrounding wood-post palisade. Seventy-five human burials also were found inside the area of main buildings and were removed.

Both Beard and Jackson uncovered material remains which may have pertained to earlier, prehistoric occupations at the site. Unfortunately, there was no clear stratigraphic control through which the deposits could be understood. Some of the more clear indicators of an earlier time, such as Archaic-period dart points, may have been brought into the mission by later peoples and perhaps recycled.

Efforts by the CWA included restoration of a building thought to have been the chapel. It later was determined to have been the granary originally and was reinterpreted in a subsequent restoration. Four major buildings were reconstructed, and the park was opened to the public. Sometime during the process, vandals dealt a major setback to mission history. The storage building housing much of the collection and excavation records was broken into; a large quantity of artifacts and files were stolen and others destroyed. The remainder of the material was sent to TARL at UT_Austin.

|

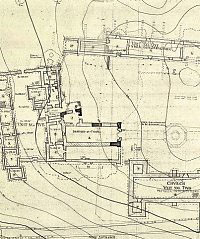

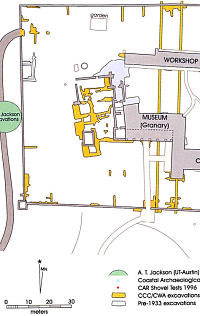

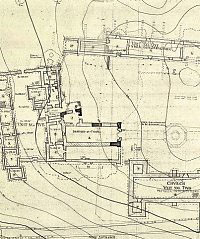

Mission Espíritu Santo was laid out within a meander loop of the lower San Antonio River, within view of Presidio La Bahia and what was to grow into the villa of La Bahia on the opposite bank. Mission Rosario was established later, to the south. National Park Service map, TARL archives.  |

Quarters for the mission Indians changed from jacal structures to more permanent stone housing during the 1760s. Photo of exhibit at Mission Espíritu Santo State Historic Park, courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Presidio de la Bahia, shown in 1935, played a critical role in the establishment of the missions and Spanish settlement at the final inland location. Soldiers from the presidio were charged with protecting the friars and native neophytes at both missions as well as helping guard the roads and mission herds. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife.  |

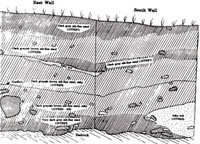

Trench in the midden deposit dug by A. T. Jackson shows the stone fence, still standing more than 7-feet- tall, that enclosed the mission. Jackson notes the midden deposit at this point is 46 inches deep, with the fence extending 46 inches above. TARL archives.  |

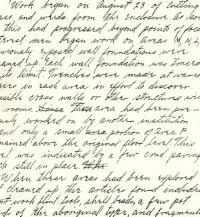

"Summary of Finds" written by A. T. Jackson after completion of his 1933 work at the mission. TARL archives.  |

Mission compound, 1936, showing walls and features mapped during investigations by the Civilian Conservation Corps. National Park Service map, TARL archives.  |

Page from field notes written in 1936 by Roland Beard, who directed the Civilian Conservation Corps excavations at the mission. Work during this time was focused on locating structural remains and other architectural features preparatory to reconstruction of the mission. TARL archives.  |

|