U.S. forts and settlements in the

Rio Grande frontier after the Civil War. Cattle trails

from south Texas to markets in the north mark the development

of the cattle industry.

|

Mexican cowboys branding cattle in

south Texas. The rise of the cattle industry after the

Civil War spurred raids and rustling by Indians and

bandits. Courtesy Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

|

Ruins of structural foundation at

Fort Inge with Inge Hill in the distance. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Texas longhorn. After the Civil War,

thousands of wild longhorn cattle were driven up trails

to high-paying markets in the north. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Yucca in bloom in south Texas. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Fort Clark entertainment, 1887. Costumed

officer and wives shown performing the Gilbert and Sullivan

operetta, "The Mikado." Photo, Vinton Trust.

|

Fort Clark today. The post has become

a private resort, with the old parade ground now used

as a golf course. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

|

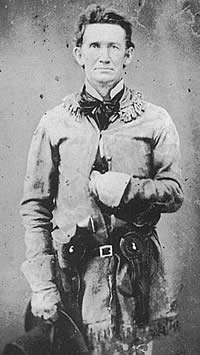

United States troops vacated all of the Texas

forts when the state seceded. "Rip" Ford's Texas

Mounted Rifles were primarily responsible for defense of the

border against Indians, Mexicans, and United States forces

early in the Civil War, and Ford returned to the Rio Grande

late in the conflict to participate in its last battle.

The border posts were the first to be reoccupied

by the U.S. Army after the war ended. The army had some 40,000

soldiers in the state by the fall of 1865, most located either

among the population centers to assist in Reconstruction duties

or on the Rio Grande to guard against the French who were

then occupying Mexico.

Within two years, the wartime volunteer units

had mustered out of service, and the remaining regulars numbered

only about 5,000. The units posted to the Rio Grande included

the 41st Infantry, a regiment of black enlisted men and white

officers. Colonel Ranald Mackenzie located the unit's headquarters

at Ringgold Barracks, and by the fall of 1868, the 41st provided

garrisons for Fort Clark, Fort Duncan, and Fort Inge. It shared

Duncan and Inge with companies of the 9th Cavalry, a regiment

also manned by black troopers and white officers.

When Company D of the 41st Infantry arrived

at Fort Inge, it was commanded by Lieutenant John L. Bullis.

Over the next 15 years, Bullis would become almost legendary

on the western frontier for his leadership of the army's Seminole-Negro

Indian scouts.

Fort Inge was abandoned in the spring of 1869.

The 41st Infantry's headquarters were transferred to Fort

McKavett, and the regiment was combined with the 38th Infantry

to form a new regiment, the 24th Infantry. From 1870 through

1872, three black units—the 9th Cavalry and the 24th

and 25th Infantry—provided the garrisons for Forts Clark

and Duncan.

By the mid-1870s, increased traffic and commerce

had combined with the rapid development of a cattle industry

to make the Nueces Strip a target-rich environment for Indians

and outlaws from both sides of the Rio Grande. The army's

pre-Civil War supply system had been instrumental in developing

wagon roads between Corpus Christi and Laredo (Fort McIntosh),

Laredo and Fort Duncan, and San Antonio and Fort Clark. New

communities had grown up near the forts—Brackett (or

Brackettville) near Fort Clark, Uvalde (an anglicized tribute

to the Spanish soldier Ugalde) near Fort Inge, and Eagle Pass

near Fort Duncan. They furnished materials and civilian labor

for army construction projects and served as supply centers

for the ranches that began to grow up in the region.

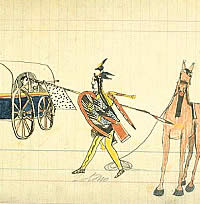

Spanish-Mexican cattle roamed wild by the hundreds

of thousands in south Texas after the Civil War. Locally,

they were worth as little as $2 per head, but on the northern

markets they brought $40 or more. Development of a system

to reach those markets set off an "open season"

of cow hunting in the brush country. Rustling and trafficking

in stolen livestock became profitable enterprises.

In 1875, a gang of about 30 outlaws terrorized

travelers and residents in and around Corpus Christi. A wounded

member of the band told his captors that the gang had come

from south of the Rio Grande in several smaller groups, and

had rendezvoused near the town with the intention of sacking

it completely. Texas Governor Richard Coke immediately directed

Leander McNelly, captain of a special company of rangers,

to deal with problems on the border.

As matters developed, international banditry

was beyond the effective control of state forces. The situation

ultimately improved only because of a series of U.S. Army

incursions into Mexico that could have provoked open warfare

between the two nations. The first of these expeditions, in

the summer of 1876 and fall of 1877, were directed by "Pecos

Bill" Shafter, commander at Fort Duncan. Shafter relied

primarily on 10th Cavalry troopers—the original "buffalo

soldiers"—and Bullis's Seminole-Negro Indian scouts,

supported by detachments of 24th and 25th Infantry. Several

attacks were made on Lipan or Kickapoo camps, most with some

degree of success.

Mexican authorities protested, but took no action

until Mackenzie led a larger expedition across the Rio Grande

in 1878. The effort was notable mainly for the confrontation

it produced with a Mexican army. Conflict was avoided, however,

and the affair prompted Mexico to keep a stronger military

presence near the border that helped suppress raiding in Texas.

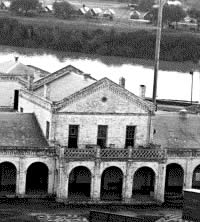

Brackettville became the county seat of Kinney

County when it was organized in 1876. To the west, an agricultural

development sprung up around irrigation canals fed by San

Felipe Springs. The small town, San Felipe del Rio, received

a post office in 1883, shortened its name to Del Rio, and

became the county seat of Val Verde County in 1885.

Revolutionary activity in Mexico spilled over

the border into Texas after 1910, and the U.S. Army sent forces

across the Rio Grande in 1916. Although troops from Fort Clark

and Fort Duncan were not directly involved in the operation,

the political unrest provided sufficient reason for the army

to maintain its presence all along the international boundary.

Soon, the United States was preparing to enter World War I,

and both Fort Clark and Fort Duncan received a new lease on

life. Duncan became a training facility, and had 16,000 soldiers

on post in 1916.

At war's end, however, the futures of the two

forts were set on different paths. The army abandoned Fort

Duncan in 1927. The City of Eagle Pass began maintaining the

property, and in 1935 turned it into a park. With the onset

of World War II, the army accepted use of the property for

an officers club and swimming pool for personnel of the Eagle

Pass Army Airfield. The property has since reverted to historic

status. Seven of the original buildings remain, and the former

post headquarters houses a museum.

Fort Clark became home to the Fifth Cavalry

and was refurbished in the 1930s. The post entered its twilight

years as another world war approached. Its troopers participated

in cavalry war games near Marfa in 1936. Its last regular

garrison went to war in 1944, and the fort became a camp for

German prisoners of war. The army abandoned Fort Clark in

1946 and sold it for salvage. The property was operated as

a corporate retreat until 1971, when it became a residential

development. Most of the buildings have been converted to

private use. The Fort Clark Historical Society maintains a

museum in the former post guardhouse.

|

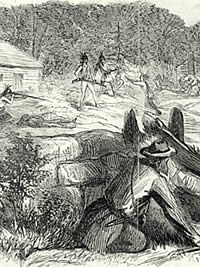

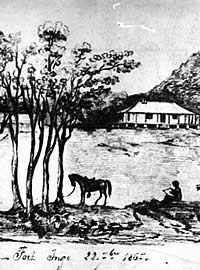

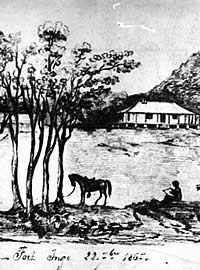

Detail of Fort Inge, drawn in 1867,

shortly before it was to be abandoned. The brush-covered

shelters, or "ramadas," on right, shelter

the tents of black soldiers posted there after the Civil

War. U.S. flag flies atop the basaltic hill known as

Pilot's Knob. Courtesy National Archives.

|

Buzzards roosting above Las Moras

creek at Fort Clark. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Drill at Fort Ringgold, Rio Grande

City, circa 1886. Like several of the border posts,

Fort Ringgold (formerly called Ringgold Barracks) was

to remain in operation until after World War II. Photo

from Crimmins Collection, Center for American History,

UT-Austin (CN# 02717).

|

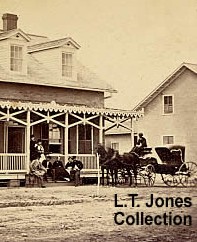

Officers quarters at Fort Brown.

Photo courtesy of Lawrence Jones, III. View

large image. |

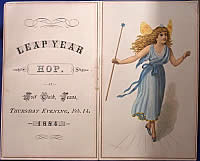

Dance card from an 1884 Leap Year

"Hop" at Fort Clark. Dances, plays, and musical

evenings provided social opportunities and entertainment

at the post, particularly in later years. Fort Clark

Museum.

|

Once used as accommodations for soldiers,

this and other structures at Fort McIntosh now house

Laredo Community College. Photo by Mary Black.

|

|