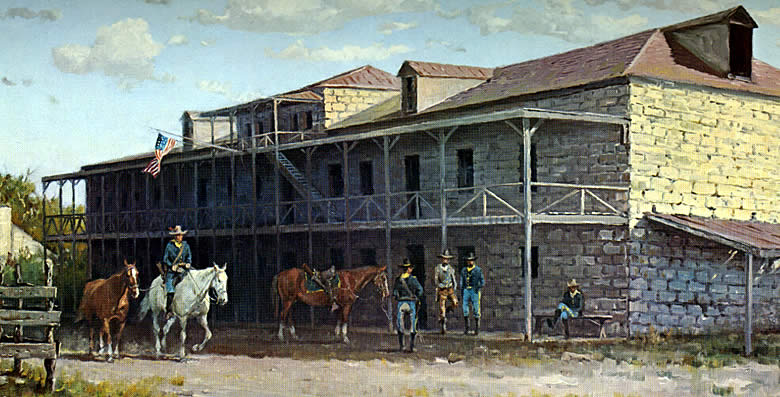

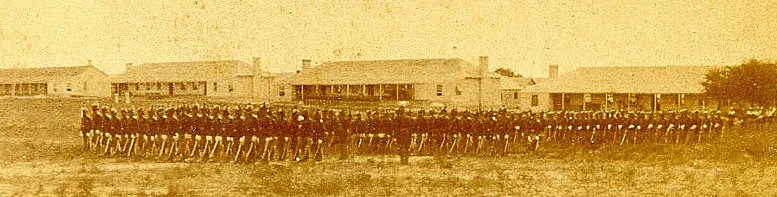

An "anachronism between two

world wars," troopers of the 5th Cavalry pass in

review, May 1939, Brig. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright commanding.

Detail of Ekmark photo. Click to see full image. Courtesy

Fort Clark Historical Society.

|

Gen. George S. Patton, Jr. The former

Fort Clark regimental commander died in France in 1945,

a year before the post closed. Photo by U. S. Army Signal

Corps, courtesy Library of Congress.

|

The clear waters of Las Moras springs

were a balm for Indian and Anglo travelers as well as

for the U.S. soldiers garrisoned at Fort Clark. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Hidden behind a burned-out façade,

the remains of post headquarters exemplify some of the

finest stone masonry at the fort. The construction date,

1857, can be seen dimly above the door. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

|

Long after the horse soldiers' time had passed,

Fort Clark was still a cavalry post. Wheeling in dusty drills

and negotiating narrow canyon trails, the troopers of the

5th Cavalry maintained the army's historical presence on the

Rio Grande. They were an anachronism between two world wars.

They also were heirs to a romantic tradition.

The regiment had originally been organized in 1855 as the

2nd Cavalry and led by Albert Sidney Johnston and Robert E.

Lee. By 1938, regimental commander George S. Patton Jr. stood

at the end of a line of officers distinguished by their dash

and daring. Patton died in France in 1945, one of the most

renowned field generals of the 20th Century. Fort Clark was

abandoned early the next year, a costly relic of American

frontier warfare.

Today, the traveler turning south off U.S. Highway

90 at Brackettville enters the residential community of Fort

Clark Springs, the remains of one of the U.S. Army's longest

occupations in Texas. Up the hill, a bronze statue stands

post above the clear waters of Las Moras Creek. It is a figure

reminiscent of the traditional ceremony acknowledging a fallen

comrade—the solitary horse, trooper's boots reversed

in the stirrups of an empty saddle.

Most of the fort's remaining 19th Century buildings

are in private use. Officers' quarters and enlisted men's

barracks—some dating from the 1850s—face the first

parade ground, now part of a par 3 golf course. The charred

remains of the old post headquarters still bear the date,

"1857," etched in the soft limestone blocks above

the original doorway. Down the hill and past the site of the

first commissary is one of the largest spring-fed swimming

pools in Texas, built in 1939 when General Jonathan Wainwright

commanded the post.

The springs of Las Moras—"the mulberries,"

in Spanish—probably attracted travelers for thousands

of years. By the late 1700s, the site was a stop on the eastern

branch of the Comanche trail from the southern High Plains

into Mexico. Perhaps because of the exposure to Indian raiders,

no Spanish or Mexican settlement took hold there.

Between 1830 and 1833, an English-born physician

named John Charles Beales secured about 50 million acres worth

of empresario contracts to settle 1,450 colonists on

lands north of the Rio Grande. Under the auspices of the Rio

Grande and Texas Land Company, Beales in 1833 began settling

Mexican and immigrant American, English, and German colonists

on the banks of Las Moras Creek a few miles downstream from

the springs. The settlement, named "Dolores," clung

to the poor soil for three years despite harsh climate and

Indian raids.

The beginning of the Texan revolt against Mexico

and the approach of Santa Anna's troops finally scattered

the settlers in 1836. One large wagon train en route to Matamoros

was attacked by Indians, and the colonists were massacred.

The village of Dolores was never reoccupied, although its

remnants became a rendezvous point for traders, trappers,

and other frontiersmen.

The first significant party of Anglo-Americans

to pass this way was led by U.S. Army lieutenants W.H.C. Whiting

and William F. Smith, returning to San Antonio after an expedition

to El Paso in 1849. Within a few months, a larger expedition

followed. Colonel Joseph E. Johnston, the army's senior topographical

engineer in Texas, was directed to mark a road westward from

San Antonio to El Paso, generally along the Whiting-Smith

route . Johnston was attached to a party of six companies

of the 3rd Infantry under Major Jefferson Van Horne. The expedition

included 275 wagons, 2,500 head of livestock, and a group

of emigrants on their way to California.

In 1852, the Army established a new chain of

forts to guard the western frontier of Texas settlements.

Major Joseph La Motte and two companies of the 1st Infantry

bivouacked at Las Moras Springs in June and named their camp

"Fort Riley." In July, the government leased the

land from San Antonio businessman Samuel Maverick for a term

of 20 years. That same month, the new post was named "Fort

Clark," in honor of Major John B. Clark of the 1st Infantry

who had died in the Mexican War.

The first temporary buildings constructed were

an adjutant's office, a bakery, and a guardhouse. The post

was inspected in 1853 by Colonel W. G. Freeman, who reported

that the troops were at work constructing quarters for themselves.

By the end of 1857, they had added a headquarters building,

hospital, and permanent bakery.

|

Sunset behind the Patton House. Built

in 1888, the wide, balconied Staff Officers Quarters

accommodated regimental commander George S. Patton during

the post's final years. The fort today is a privately

owned resort.

Photo by Susan Dial.

Click images to enlarge

|

Sgt. Ben July, Seminole-Negro Indian

Scout, shown in late 1890s in front of jacal hut, Seminole

camp near Fort Clark. The famed scouts were a critical

factor in campaigns against Indians. Photo courtesy

Fort Clark Historical Society. Click to see full image.

|

|

Mulberry tree for which the springs,

Las Moras—the Mulberries—are named.

|

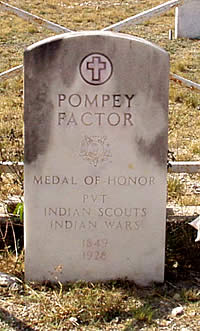

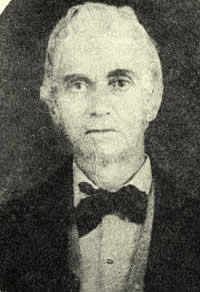

Samuel A. Maverick. The San Antonio

businessman leased land at Las Moras springs to the

U.S. government in 1852 for the establishment of Fort

Clark.

|

"Apache Indians Attacking Wagon

Train." Scenes such as this, drawn in 1854, illustrated

the dangers to immigrants on the southwest Texas frontier.

Image from Bartlett's Personal Narratives, courtesy

Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

|

|