The dusty, flat landscape of the

Trans-Pecos is broken abruptly by mountains such as

the Chisos, Chinati, Glass, and Davis rising high above

the desert floor. This scene is in Presidio County,

near the Rio Grande. TARL Archives.

|

Jumano Indians standing atop the

walls of their pueblo watch the arrival of Spanish explorers.

According to explorer Hernán Gallegos, who traveled

the Trans-Pecos near La Junta in 1581, the early farmers

greeted them with "great merriment." Drawing

by Hal Story (Newcomb 1961).

|

Scene near La Junta de Los Rios, Presidio County, Texas.

Photo from TARL Archives (Presidio C-15). |

Pronghorn grazing in grasslands in far West Texas. Photo

courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife. |

From a high overlook, Indians keep

a watchful eye on a caravan of travelers trudging through

a Trans-Pecos basin in far west Texas. "Comanche

Lookout" was painted in the mid- to late 1850s

by Capt. Arthur T. Lee, who was captivated by the aboriginal

peoples and stunning scenery near Fort Davis. Image

courtesy of the Rochester Historical Society.

|

Routes of Comanche trails from villages on the Plains.

Adapted from Weber 1982. |

Pecos River crossing near Fort Lancaster. Photo by Susan Dial. |

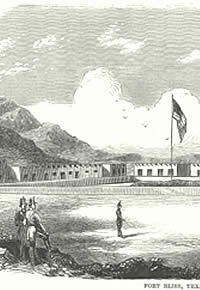

Fort Bliss, Texas. Established as a camp in 1849, it was

relocated to its present position in what is now El Paso.

|

The Trans-Pecos frontier after 1855

and prior to the Civil War.

|

|

Much of the history of the Trans-Pecos region

of southwestern Texas has been of peoples on their way to

some place else. The Spanish mostly went around it. Comanche

and Kiowa raiders rode through it from the north on their

way to Mexico. Anglo-Americans came from the east, headed

for the California gold fields and western cattle markets.

In time, the travelers and their trails drew the attention

of the United States Army.

Prehistoric peoples lived and traded along

the middle Rio Grande—named El Rio del Norte by the Spanish—for

thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. In 1535,

the wandering Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca found Jumano and

other native groups farming the land at the junction of the

Rio Grande and the Rio Conchos—la junta de los rios—opposite

the site of modern Presidio, Texas.

Two Spanish exploratory expeditions in the early

1580s came down the Conchos, passed through la junta, turned

northwest, and followed the Norte toward its upper reaches.

In 1598, Juan de Oñate was authorized to settle the

lands within the modern boundaries of New Mexico. He traveled

over the Chihuahuan plateau to reach the Rio Grande some 150

miles upstream from la junta, and memorialized his crossing

of the river as El Paso del Rio del Norte. He then followed

the river to the pueblos of the north, where he settled his

colonists and established the town of Santa Fe.

Oñate found the Puebloans trading with

Plains Indians who brought buffalo robes to exchange for corn

and other agricultural products. The outlanders—the Spanish

called them vaqueros because of their trade in "cow"

hides—were the Plains Apache. The center of this trade

was the Pecos Pueblo, across the mountains to the east of

Santa Fe and near the headwaters of the Pecos River.

The province of Nuevo Mexico grew steadily,

if somewhat slowly, but the harshness of a succession of Spanish

governors led to an Indian revolt in 1680. The Spaniards withdrew

to the south and took refuge near Oñate's crossing

of the Rio Grande. Their northward advance stymied, the Spanish

began to dig in along the middle stretch of the river and

to establish missions at the Paso del Norte and la junta.

These missions remained after the Spanish returned to Santa

Fe. In 1760, the Spanish would establish Presidio de la junta

de los Rios Norte y los Conchos—known more simply in

later years as Presidio del Norte—to protect the missions

at the junction of the Rio Grande and Rio Conchos.

The missionary efforts at la junta were plagued

by Spanish slavers who captured local Indians and carried

them south to work in the silver mines. Apaches who visited

the Puebloans of New Mexico likewise were periodically abducted

by the Spanish and transported to the interior of Mexico.

When Comanches began to intrude on the Apache range in the

early 1700s, they attacked the pueblos and the nearby New

Mexican settlements. In desperation, the Spanish government

in 1786 made an alliance with the Comanches in which they

combined to make war against the Apaches. In addition to other

terms, the Spanish New Mexicans offered the Comanches a horse

and bridle and two knives for each Apache captive brought

to Santa Fe.

Throughout the remainder of the Spanish colonial

period and 25-year interval of Mexican rule, the settlers

of New Mexico were able to maintain relatively peaceful trade

relations with the Comanche. But that peace was maintained

at a tremendous cost that was paid by settlers in the northern

Mexico provinces of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, and Zacatecas.

As the Apache lost control of the Plains and scattered into

the mountains of Mexico and the Trans-Pecos, the Comanche

began to raid the Mexican settlements south of the Rio Grande.

Captive Mexicans would be carried north, and some would be

brought to the New Mexico settlements to be ransomed.

The Comanche Trail from the High Plains into

Mexico—sometimes called the "Comanche War Trail"

or the "Comanche Trace"—is shrouded in legend

and mystery. It appears not to have been one trail, but several

that converged somewhere on the Plains or in the Trans-Pecos,

passed by the prodigious springs at the present city of Fort

Stockton, and diverged again to cross the Rio Grande at multiple

points. Raiders following the upriver, or western, trails

could strike at Chihuahua and Durango; those following the

eastern branches could attack Coahuila and Zacatecas.

The Mexicans' successful revolution against

Spanish rule opened a new era of international trade along

the famous Santa Fe Trail, which ran from Independence, Missouri,

into northern New Mexico. From Santa Fe, the trade extended

south through the Paso del Norte, and on to Chihuahua City.

When the United States and Mexico went to war in 1846, one

of the U.S. Army's invasion routes into Mexico followed the

Santa Fe-Chihuahua Trail.

After three years of war, the United States

in 1848 obtained the land west of the new state of Texas—the

territory comprising the modern states of New Mexico, Arizona,

and California. As word of discovery of gold in California

began to reach the east, exploratory expeditions and immigrant

parties began to enter the Trans-Pecos in search of a viable

route to the Pacific. Texas rangers John C. Hays and Samuel

Highsmith attempted to map such a road, but became hopelessly

lost. They probably were saved only by fortuitously stumbling

upon a trading post known as Fort Leaton.

Chihuahua Trail freighter Ben Leaton had purchased

property near la junta in 1848. He expanded upon existing

structures to establish a home, trading post, and private

fort. The Hays-Highsmith party recuperated at Leaton's place

for 10 days before leaving for San Antonio, which they reached

in December, 1848, and where they reported that they had found

a practicable wagon route from San Antonio to the Presidio

del Norte.

Within two months after the return of the Hays-Highsmith

party, U.S. Army lieutenants W.H.C. Whiting and William F.

Smith departed San Antonio with orders to try to find a viable

route west, using the dubious Hays-Highsmith experience to

reach the Rio Grande at Presidio del Norte. The expedition

first headed northwest, passing through the German settlement

at Fredericksburg before reaching the San Saba River. It followed

the San Saba to its headwaters, then headed west beyond the

Pecos River and south to Fort Leaton.

The Whiting-Smith party followed the Rio Grande

northwest to the Paso del Norte, but decided to return on

a more direct route that bypassed Fort Leaton and reached

San Antonio by way of the Devil's River, Las Moras Springs,

the Nueces River, and the Alsatian village of Castroville.

Fort Leaton, believed to be the largest adobe structure in

Texas, would eventually fade into obscurity. Ben Leaton died

in 1851, but not before Mexican authorities accused him of

selling guns to Comanches in return for stolen horses.

By mid-1849, the army had plotted the wagon

road that became known variously as the "government,"

"lower," or "southern" road west from

San Antonio. In September, Captain Jefferson Van Horne and

four companies of the 3rd Infantry traveled through the Trans-Pecos

and established a camp at the ranch of Benjamin Franklin Coons,

across the river from the Mexican town that had become known,

simply, as "El Paso." The army's post would be abandoned,

relocated, and ultimately named Fort Bliss. The Anglo town

that grew up across the river from Mexican El Paso would be

known as "Franklin."

In the meantime, the army's and the public's

desire for means of transcontinental communication and commerce

was recognized by Henry Skillman, a veteran trader on the

Santa Fe-Chihuahua Trail. In 1851 he was awarded a contract

for U.S. mail service from San Antonio to Santa Fe via Franklin.

By December, Skillman was offering passenger service.

Skillman formed a partnership with George Giddings

in 1854, and the two attempted to put the operation on a stronger

financial footing. But the business would always be endangered

by Lipan Apaches on the eastern end of the route, Mescalero

Apaches in the mountains of the far western Trans-Pecos, and

Comanches and Kiowas in between. In less than two years, the

Giddings-Skillman operation lost more than $54,000 worth of

livestock, wagons, and buildings to Indian attacks.

Two U. S. Army posts guarded the gateways from

the interior of Texas into the Trans-Pecos. Fort McKavett,

near the headwaters of the San Saba River, protected the "upper"

road through Fredericksburg . Fort Clark, near the Rio Grande,

protected the "lower" road through Castroville.

But a similar military presence was needed farther west, and

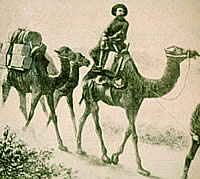

in 1854 the army established a post near Limpia Creek in the

mountains of the Trans-Pecos. It was named Fort Davis, after

United States secretary of war Jefferson Davis. The following

year, Fort Lancaster was established on Live Oak Creek near

its confluence with the Pecos River.

|

Wildflowers in the Davis Mountains.

The lush vegetation in the mountains of the Trans-Pecos

provides a stark and welcome contrast to the Chihuahua

desert.

Photo by Susan Dial.

Click images to enlarge

|

Traces of different cultures: artifacts

from the Polvo Site, located downstream from the confluence of the Rio Grande

and Río Conchos—La Junta de los Ríos.

The area was inhabited by Patarabueye/Jumano Indians

from about 1200 to 1400 and later by Spaniards and Mexicans.

Drawing from Cloud et al., 1994, courtesy of the Texas

Historic Commission. Click for more detail.

|

|

The missionary efforts at La Junta were plagued

by Spanish slavers who captured local Indians and carried

them south to work in the silver mines.

|

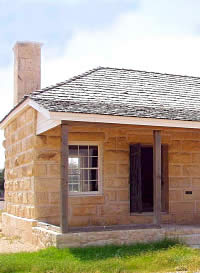

Ruins of freighter Ben Leaton's trading post, established

near La Junta in the 1840s. Called Fort Leaton, it was

not an army post but a family fortress and trading post,

providing shelter and sustenance to travelers between

Eagle Pass and El Paso. The adobe compound has now been

restored by Texas Parks and Wildlife. Photo, TARL Archives.

|

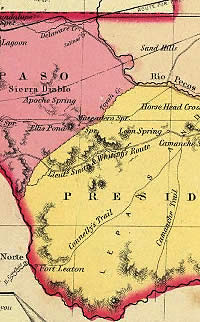

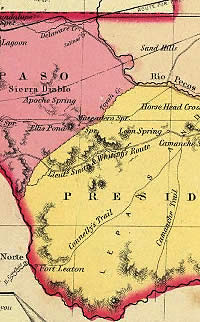

Far west Texas, showing Presidio del

Norte and confluence of the Rio Grande and Rio Conchos.

Lt. Smith's and Whiting's road and Connelly's routecrosses

the Comanche trail near Comanche Springs. Slightly to

the northeast is Horsehead Crossing, the flat, shallow

ford where hundreds of wagons crossed the Pecos River.

Inset of map by G. W. Colton, 1856, courtesy of the

David Rumsey Map Collection. Click to enlarge.

|

Emigrants bound for California crossing the Pecos River

at Horsehead Crossing, west Texas, circa 1850. |

Emigrant routes across the vast open

spaces of the Trans-Pecos frontier are clearly shown

in this map.

|

Traces of the old stagecoach road

from San Antonio to El Paso are dimly visible as a light

vertical streak descending from a gap in the hills above

Fort Lancaster. The ride over stony hills was treacherous

enough; stops along the way, amid cactus and mesquite

scrub, was often worse. As one 1850s traveler wrote

of the Trans-Pecos: "One of the most remarkable

features of this inhospitable region is the hostility

with which every plant bears arms… ." Photo by Susan Dial.

|

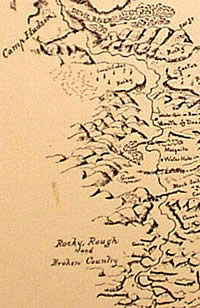

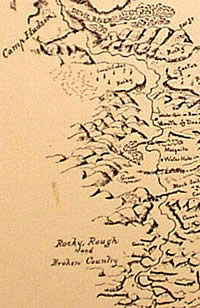

"Rocky, rough and broken country…." Inset

of Topographical Sketch of the Road from Fort Clark to

Fort Stockton, 266 miles, October to November, 1867; and

camps of Bvt. Lt. Col. A. J. Strong. Camp Hudson is shown

at top, midway between Forts Clark and Davis. Courtesy

Fort Stockton Historical Museum. |

|