Former Travis County district clerk Ernst

Hallman moved to his hill country lands in 1882 to raise sheep.

Photo circa 1875, courtesy Travis County Bar Association and

Senator Ralph Yarborough.

Click images to enlarge

|

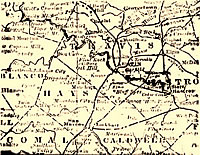

Section of Map of Texas circa 1888, showing

location of Colberg, where Hallman served as postmaster for

two years. Colberg was also the name of his birthplace in

Prussia. Map courtesy of Center for American History, Swante

Palm Collection.

|

The southeast side of the building was

the more ornamented, with lintels over the door and window.

During the 1880s, this side was likely the front door. Although

the road has now been moved, an aerial map from the 1930s

shows the faint traces of an old road winding past this side

of the building and on throughout the Barton Creek community.

Photo by Tom Hester.

|

|

In 1882, prominent Austin businessman Ernst Hallman

determined to make a dramatic change in his life. Ten years previously,

the native of Colberg, Prussia, had been terribly injured in a train

accident in Manor, Texas. As a result, both his left leg and right

foot had to be amputated. Although he continued working as a district

clerk for Travis County for several years afterward, he apparently

was ready to leave city life behind. Having purchased more than

2400 acres of raw land west of the city, Hallman and his wife, Johanna

Schenck Hallman moved to the Hill Country to raise sheep.

Little is known of the outcome of his venture. For

even the toughest and most able bodied of men, the tasks of establishing

a ranching operation must have been daunting. Even today, the rocky

roads traversing the property Hallman once owned are rough and,

during bad weather, treacherous. And yet postal records tell us

that from 1883 to 1885, he also served as the postmaster of the

community of Colberg in the "Hays/Travis area." Did the

native of Colberg, Prussia, give this small enclave the name of

his birthplace?

Today, all that is left on the land he once owned

is a well-constructed stone building on a high ridge overlooking

a tree-lined hollow. The 16-x-35-foot building is coursed masonry:

hand-cut limestone laid with a mortar of burned lime and sand. The

interior is dirt-floored and one-room wide, although a frame partition

divides the interior into two sections.

In the fields surrounding the building, patterns of

rock are aligned in large rectangular patterns, perhaps the remnants

of corrals or pens. Piles of cut wood, nails, and other building

materials indicate that other structures, some say bunkhouses, once

stood in the area as well.

Based on the artifacts, the stone structure

and outbuildings were used chiefly as a residence and for

farm or ranch purposes. As a group, the artifacts date the

site from the 1870s to the early 1900s: fragments of heavy

white tableware popular in the 1880s and 1890s, sherds of

stoneware crocks and churns; bits of bitters, Schnapps and

beer bottles from the 1870s to early twentieth century. Parts

of a cast iron stove, horseshoes, a metal pail, baling wire,

and other objects were found in the adjacent fields.

Yet, ranchers in the area today clearly recall

their grandparents' stories describing the stone building

not only as a store but also as containing wooden post office

boxes, a combination of services typical in rural communities.

Small country stores chiefly carried basic items required

for everyday life such as flour, sugar, coffee, and salt as

well as a limited supply of dry goods and such non-staple

items as snuff, bitters, medicine, liquor, and candy. The

storeowner and his family often lived in one end of the store

partitioned off from the commercial side. Because the objects

sold in the store were intended largely for household use,

they would be largely indistinguishable from artifacts found

in a rural dwelling. For archeologists sorting through these

remains, the problem of the building's function was frustrating,

and is, as yet, not fully resolved.

Whatever his role—rancher, storekeeper,

postal clerk, or all three—Hallman remained at the scenic

hilltop compound for only a decade, moving back to Austin

with his family shortly before his death in 1892. His widow

and two daughters retained ownership of the property until

1907. Today, the small hollow at the base of the hill still

carries his name, although the spelling has changed over time.

|

|

For even the toughest and most able bodied of men, the

tasks of establishing a ranching operation must have been

daunting.

|

Strong springs sustain fern-lined pools

and a small stream in the tree-lined hollow below the stone

building. In the creek, investigators found cut limestone

blocks which are thought to be the remains of a springhouse,

where foods and dairy products could be kept cool. Photo

by Susan Dial.

|

Fields adjacent to the stone building contained

alignments of stone and small piles of building debris. Photo

by Susan Dial.

|

Rectangular patterning in the lines of

stone suggest they are the remnants of stone walls, perhaps

corrals or pens for sheep or other animals. Photo by Susan

Dial

|

|