Around 2,000 years ago aboriginal peoples of the upper Texas coast began to visit Galveston Island and take advantage of its ready access to Galveston Bay, the Gulf of Mexico, and the tidal passes linking the two. At first people probably came to the newly formed barrier island only sporadically, as the island continued to build seaward and upward to become a more substantial land mass. But by about 1300 years ago (A.D. 700) one group began to frequent a narrow inlet cutting into the back of the western end of Galveston Island. They camped overlooking the inlet, today known as Eckert Bayou, along the highest topographic feature in the central stretch of the island, a low rise known today as Mitchell Ridge. The ridge rose no more than ten feet above sea level, but that was enough for habitation except during major storm surges, such as those accompanying hurricanes.

The locale became a favored spot for late fall and winter camps, the time of the year when large black and red drum frequented the bays and tidal passes. Being mobile peoples who lived off the land for all needs, they also collected shellfish in the shallow bay, hunted and trapped rats and other small game on the island, and gathered wild plants such as the roots of plants that grew thickly in the swales between the island’s sandy ridges.They left behind unmistakable evidence of ordinary daily life—dense concentrations of refuse such as discarded shells, animal bones, tool-making debris, and broken tools.

They also began to bury their dead in small cemeteries they established around the edges of the main occupation area and along the ridge farther way from the inlet. Each tightly clustered cemetery was used from time to time over spans of several hundred years, yet the burials almost never intruded into one another, suggesting that the graves were marked and placed within designated burial grounds used by small kin groups.

Peoples returned again and again to Mitchell Ridge during the final millennium of the prehistoric era. The descendants of the peoples who had long considered the sandy ridge a traditional haunt may well have witnessed an extraordinary event in 1528. In November of that year a makeshift barge capsized on the beach of a narrow island along the upper Texas coast, spilling out several dozen Spanish men, the last survivors of the ill-fated expedition Narváez expedition to La Florida. The castaways encountered the aboriginal inhabitants of the island in what may have been the first time Europeans and the native peoples of the upper Texas coast met face to face.

The island the Spanish called Isla del Malhado (Island of Misfortune) in the famous account of survivor Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, has been identified by many scholars as being Galveston Island. If so, it is likely that those who camped at Mitchell Ridge came in contact with Cabeza de Vaca. While there is no convincing “smoking gun” archeological evidence of this hypothesized encounter, Mitchell Ridge continued to be used by aboriginal peoples through the mid 18th century.

As is well known, the early historic era was a time of great turmoil and tragedy for Indian peoples across North America. Old World diseases decimated aboriginal populations across the continent as the invading peoples colonized newly claimed domains. The Spanish attempted to convert native peoples to Christianity, gather and resettle them around Spanish enclaves, and put them to work. In contrast, the French more often tried to befriend Indian peoples and to build trade networks funneling animal hides and tanned leather to Europe.

Yet the upper Texas coast remained a remote wilderness that was not settled by the newcomers until after the late 18th century. Graves at Mitchell Ridge dating to the 17th and 18th centuries show that the local natives interacted with European colonists through trade and probably through interbreeding. There are also indications that some of those buried at the site were refugee Indians from the Southeast and perhaps other areas of Texas. Remnants of these ethnically mixed groups of native peoples may have survived into the early 19th century in the Galveston Bay area, but by the late 18th century they ceased to visit Mitchell Ridge. Historic accounts of the final centuries suggest that Karankawa peoples frequented Galveston Island and it is possible that these native newcomers may have camped at the site. If so, they left very little, if any, recognizable trace. The peoples whose ancestors frequented Mitchell Ridge for many generations were almost certainly members of one of the western Atakapa-speaking groups, such as the Akokisa.

In This Exhibit

This exhibit forms a narrative telling the story of the Mitchell Ridge site through time, and of the archeological research upon which it is based. Follow the Mitchell Ridge story section by section or visit sections of interest.

Setting explains the formation of Galveston Island and summarizes the ecology of the Galveston Bay area.

Chronology outlines the native history of the Galveston Bay area through time and lays out the chronological framework used for Mitchell Ridge.

Ethnohistory details what can be gleaned from historic accounts about the upper Texas coast and the Galveston Bay area in particular from the 16th century arrival of the Spanish through the demise of the region’s native peoples in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Investigations reviews the history of archeological research at Mitchell Ridge from its beginnings in 1974 through the major excavations of 1992.

Occupational Evidence summarizes the critical data relating to the site’s stratigraphy, occupational features, and material culture, except that from the cemeteries.

Mortuary Patterns reviews the four cemeteries at Mitchell Ridge and describes some of the most informative graves.

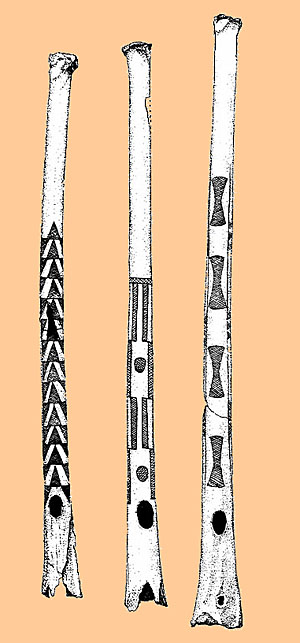

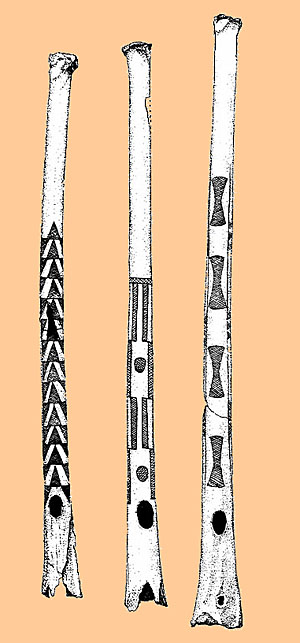

Grave Goods categorizes and describes the grave offerings and inclusions that accompanied certain burials, including shell ornaments, whooping crane whistles, rattles, other bone artifacts, stone tools, ochre, glass trade beads, metal artifacts, and food offerings.

Life and Death at Mitchell Ridge synthesizes what has been learned about the peoples who lived at the site and who buried their loved ones there. The scientific study of the Mitchell Ridge burial population has yielded many insights about aboriginal life on the upper Texas coast.

Credits and Sources acknowledges those who created this exhibit and provides references to printed sources for more information. All of the chapters of the 559-page technical report on Mitchell Ridge can be downloaded as PDF files.

|

Aerial view of the Galveston Bay area showing the location of Mitchell Ridge. Image from Microsoft Virtual Earth.

|

Aboriginal vs. Native vs. Indian vs. Native American

In this website we use these terms more or less interchangeably. The word "aboriginal" means "of or pertaining to aborigines, to the earliest inhabitants, or to native races" (Oxford English Dictionary). When capitalized, Aboriginal is often used to refer to the native inhabitants of Australia, but that is a special use of the word, not its ordinary meaning. We sometimes find aboriginal to be a better choice than "native peoples." Today the proud claim "native Texan" is often made by anyone born in Texas. For us, Texas' true native peoples are its aboriginal inhabitants, the Indian (or Native American or American Indian) peoples whose ancestors have lived in Texas and throughout North America for hundreds of generations. |

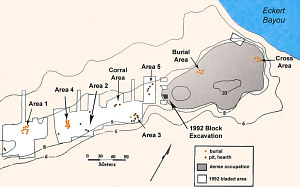

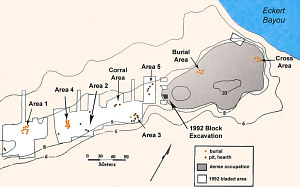

Map of the Mitchell Ridge site, 41GV66. Adapted from graphic by Robert Ricklis.  |

Musical instruments such as these engraved whistles made from whooping crane leg bones were among the grave offerings from Mitchell Ridge. Adapted from Ricklis, 1994, Figure 8.18. |

|