Grave Goods

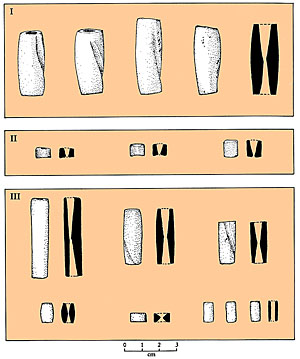

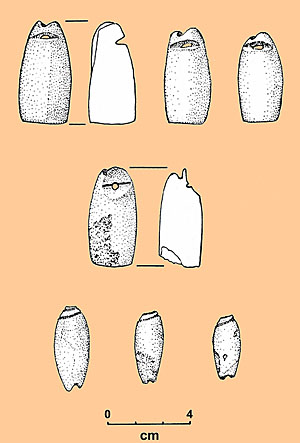

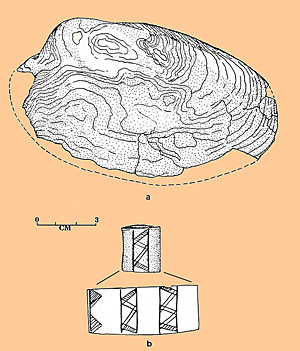

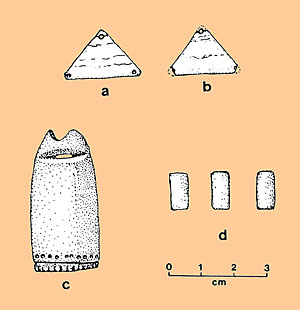

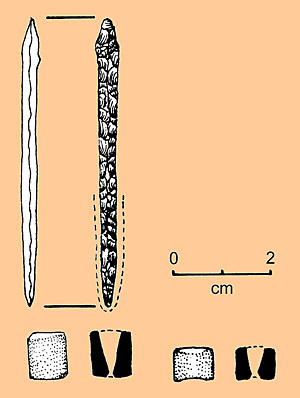

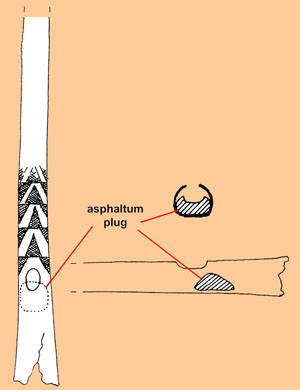

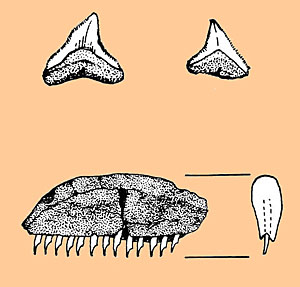

The preserved objects found in Mitchell Ridge graves give us insight into ritual life, social status, trade connections, craftsmanship, ethnic affinity, conflict, and changes through time of the native peoples who inhabited Galveston Island. In this section we categorize and summarize the grave goods and provide examples of each. Serious students of archeology will want to consult Chapter 11 of the site report which provides the essential technical detail, grave associations, and comparative analysis done by authors Meredith Dreiss and Robert Ricklis. Archeologists use various terms for what we call grave goods here, including grave offerings, funerary objects, burial inclusions, etc. We use “grave goods” because some of the artifacts found within the graves were probably not offerings, per se, but items of personal adornment that the deceased may have worn in life or may have had as part of his or her personal possessions. In the case of Burial 12, two Scallorn arrow points probably represent the embedded cause of death. Nevertheless, most of the items found in graves were intentionally buried with the deceased and must have been imbued with layers of sacred, social, and personal meaning, as is true the world over. Marine and Freshwater Shell ArtifactsShell artifacts were found in 10 of the 32 graves at Mitchell Ridge, 95% of them beads or tinklers made of one of three marine species: Lightening Whelk and two related small gastropods, Olivella and the Lettered Olive (Oliva sayana). A total of 294 shell artifacts were recovered from these graves. Shell artifacts were the only grave offering category associated with interments dating to each time period represented at Mitchell Ridge, spanning the Late Archaic to Early Historic periods. Conch Columella Beads: One-hundred shell artifacts found in graves (34% of the sample) were manufactured from the large left-handed marine gastropod Busycon perversum pulleyi, commonly named Lightening Whelk and popularly known as “conch,” a term also applied to other gastropods as well including the true conch of the genus Strombus. Of the “conch” shell artifacts found in the Mitchell Ridge graves, there is a single whorl fragment and 99 cylindrical beads made from the shell’s columella or axial pillar. These cylindrical beads predominate along the Upper Texas coast and are markedly different in shape and manufacturing process from the discoidal beds commonly found in the lower Texas coast in the Brownsville complex. The latter are flat disks made from portions of the Busycon outer whorl of the general style sometimes known as Heishi beads in the modern bead trade. Interestingly, there were also no conch pendants found at Mitchell Ridge, an ornament style found at many coastal plain cemeteries dating to the Late Archaic. The conch columella beads from Mitchell Ridge fall into three categories or styles. Style I, a large, long, thick-walled, biconically drilled bead form with minimally smoothed exteriors, was found in only a single Initial Late Prehistoric grave (Burial 7). Style II, the small chunky form drilled from only one direction, was associated with several Protohistoric graves. Style III includes both long and short versions, all of which have heavily smoothed into very symmetrical cylindrical shapes, were only found in several Early Historic graves. Most of the Style III beads were biconically drilled except for several wampum-style beads with smooth cylindrical bore holes and polished exteriors; these were probably commercially produced for the 18th century fur and skin trade market. Oliva Tinklers: These bell-shaped ornaments known as tinklers are thought to have suspended from clothing or necklaces such that they could strike one another and make a light tinkling sound. They were manufactured by cutting (or grinding) off the top of the spire above the shoulder of the shell and then cutting or drilling a hole. All 20 of the tinklers from Mitchell Ridge were made of the Lettered Olive shell, Oliva sayana. All but one were undecorated. A tinkler found near the top of the head of Feature 64, Burial 4, that of an adult male, has a design of small tick marks underlined by a horizontal line below which is a row of tiny punctations. Oliva and Olivella Beads: Oliva sayana shells were also used to make beads, as was the smaller species Olivella. A total of 251 shell beads were found in graves, including 20 made from Oliva and 126 made of Olivella. These spire-topped shells were turned into beads simply by cutting or grinding off the spire, which allows a cord to pass through the center of the whorl. The Olivella beads at Mitchell-Ridge were made from the Minute Dwarf Olive, Olivella (Niteolivia) minuta, a very small thin-shelled species. So thin that it is likely the beads were made by lightly grinding the spire rather than trying to cut it off. Other Shell Artifacts: Freshwater mussel (clam) shell artifacts were recovered from three graves. One was a small poorly-preserved fragment of unknown form; it could have been a small pendant. An extremely large freshwater clam shell was placed over the area of the heart of an adult male found in the Feature 86 grave pit, which dates to the Final Late Prehistoric period. The top natural layer of this shell was smoothed off, creating a polished pearly finish, and a small hole through the shell may (or may not) have been drilled. A similar polished freshwater clam shell was found with Feature 64, Burial 1, that of an adolescent female. In the same grave pit, two small triangular mussel shell pendants were found on the sides of the head of an adult male, Burial 4. These very thin pendants have drilled holes in the apex and partially drilled holes in the other corners. Three large marine bivalves were found in graves. An ark shell, probably Andara (Lunarca) ovalis, was found near the adult male buried in Feature 64. The shell has a hole near the umbo which may have been used for suspension. Two whole bivalves with slightly smoothed edges were associated with Burial 10, an adult male dating to the Late Archaic or Early Ceramic period. These were identified as Laevicardium (Dinocardium) robustum and the southern quahog Mercenaria campechiensis, both offshore species likely collected from the Gulf beach. Bone ArtifactsWhooping Crane Whistles: Eleven bird bone whistles represent a fascinating category of funerary items at Mitchell Ridge. All are made from the ulna, the larger of the two lower “arm” (wing) bones, of the whooping crane, Grus Americana, the tallest bird in North America. Whooping crane ulnas are hollow bones with very thin walls, an adaptive feature shared by all large flying birds. The whistles from Mitchell Ridge have a single air hole, distinguishing them from flutes which have multiple air holes. Four of the whistles are decorated with geometric patterns created by finely engraved lines. Four of the whistles which have essentially intact distal ends (where the air holes are), have triangular plugs of asphaltum inside the bones opposite and partially overlapping the air holes. These served to constrict and direct the flow of air, thus “shaping” the resulting sound. Gentle attempts were made to coax sound from several of the most intact and strongest whistles to no avail. Whooping cranes are wading birds that inhabit the Gulf coastal marshlands during the winter and migrate to northern Canada during the warm half of the year where they breed. Mature whooping cranes stand almost five feet tall and have a wing span of seven and a half feet. They have a striking appearance, white bodies and wings with rusty red patches on top and back of head, and long black legs and bills. Their wings are tipped with large black “primary” feathers that are visible only in flight. Thus the long white and black birds must have been iconic symbols for native coastal peoples, representing flight and the cold-weather season. Today the whooping crane is one of the rarest birds in North America, an endangered species that came precariously close to extinction in the 1930s when the population dwindled to less than 20 birds. Since then the population has slowly, but steadily grown to over 200 as the result of protected species status and extensive conservation measures. Today most whooping cranes overwinter around San Antonio Bay on the central Texas coast and are protected by the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge. Prior to the mid-19th century, whooping cranes were numerous (15,000-20,000 according to one estimate) and widespread in North America. Although the inhabitants of the Mitchell Ridge site obviously killed some whooping cranes to make the whistles, no whooping crane bones were recovered from the occupational refuse deposits, amid the many bones of fish, deer, and rats. This suggests that whooping cranes were probably not part of the diet. In addition to the 11 definite whistles, a probable 12th whistle was indicated by fragments of a large bird ulna that were found with one of the cremations (Feature 65-A). Due to the thin and delicate nature of the whooping crane ulna, it is not surprising that most of the whistles found in the graves were fragmented. Fortunately, several were essentially intact and the lengths and essential details of all but one of the eleven definite whistles could be pieced together. The complete whistles were 25-30 centimeters (8-12 inches) in length and had a single air hole 9-15 millimeters in diameter. Four of the whooping crane whistles were decorated with finely engraved lines. Interestingly, the seven undecorated whistles all date to the Early Historic period, while the decorated whistles come from Late Prehistoric and Protohistoric graves. Rattles: Four clusters of back drum teeth and/or pebbles were associated with graves. Feature 28, a grave containing the token remains of two juveniles, was accompanied by two apparent musical instruments, a whistle made from a whooping crane ulna and a circular mass of 359 black drum fish teeth only 10 centimeters across. These teeth are thought to have been confined within a circular container, such as a large gourd or a hollowed wooden container, and are inferred to represent a rattle. Judging from the number of teeth, the rattle must have been used to make impressively loud rhythmic sounds! The other probable rattles seem to have been smaller. A cluster of three black drum teeth and five pea-sized pebbles found near the left hand of the Early Historic period Feature 64, Burial 4, may well represent a rattle. In this case, the burial also included four whooping crane whistles. One of the overlying burials in Feature 64, Burial 1, also had a cluster of pea-sized pebbles in one hand. Nearby were two whooping crane whistles. A final rattle candidate is represented by two black drum teeth found at the top of the head of child (Feature 83). Given the inferred use of drum teeth as rattles in the other mentioned graves at Mitchell Ridge as well as at several other cemetery sites in the Upper Texas Coast (such as the Harris County Boys School), the two teeth may have been part of a small rattle attached to the hair of the child. Other Bone Artifacts: Bone artifacts accompanied six burials ranging in age from Early Ceramic to the Early Historic periods. The bone artifacts are varied in form and function and include engraved and undecorated bird bone beads, socketed bone points, deer metapodial point blanks, bone hair pin(s), shark teeth, an engraved rectangular piece of bone, a bone “dagger,” an antler billet, and 13 cotton rat teeth set into an asphaltum handle. Three graves held the most varied and curious bone artifacts. The earliest grave at Mitchell Ridge, that of the adult male in Burial 10, held seven socketed bone points, four unworked distal ends of deer metapodials thought to represent manufacturing blanks for the socketed bone points,and the distal end of a deer ulna (lower leg bone) on which a sharp point had been formed. The socketed bone points are all made from the distal ends of deer metapodials (foot bones) and range in length from 4 to 8 centimeters. All were made by breaking off the proximal end of the metapodials, grinding the shanks to a point, grinding off the distal articular surfaces, and reaming out the distal ends to allow the assertion of a wooden shaft. Asphaltum hafting cement was found on the interior of all specimens. The socketed points may have been part of fishing spears or similar weapons. Virtually identical bone points made from deer metapodial bones are characteristic of the Tchula culture of the Lower Mississippi Valley and Louisiana coastal zone. They have also been documented in Archaic and Early Ceramic contexts in the Galveston Bay and Brazos delta areas of the Upper Texas Coast. Feature 87, the Final Late Prehistoric period grave of an adult male had two shark teeth in his left hand. Near his right arm was a small oblong mass of asphaltum into which 13 sharpened hispid cotton rat incisors were set in a single row. A similar artifact is revealed to be a shaman-curer’s bloodletting tool in a late 17th century historic account. Similarly, the shark teeth may have served as bloodletting tools. The man is interpreted as a shaman or curer. Feature 65, an Early Historic grave contained an adult man and a secondary cremation (65-A) accompanied by a wealth of funerary objects made from bone. These include an engraved bone pin, a bone “dagger,” two deer antler billets (flint knapping tools), and three bone points. The “dagger” is a shaped section of a long bone that has ground edges and points on both ends. Based on the size and curvature of the bone, this artifact could have been fashioned from a human femur. The bone points were fashioned from the fin spines of large fish (kingfish?). They are pointed on one end and wedge-shaped on the other. The wedge configuration probably facilitated hafting, a supposition supported by the finding of asphaltum mastic at the wedge end of one of the points. Stone ToolsStone tools made of flaked chert were found with eight burials. These included a few drills, projectile points, and small bifaces, as well as numerous flake tools and prismatic blades. Interestingly, in contrast to many Archaic cemeteries along the coastal plains, only two graves contained projectile points. Burial 10, the only grave at Mitchell Ridge dating to the Early Ceramic period (equivalent to the latter part of the Late Archaic), yielded a Godley dart point and probably at least one other dart point as discussed in Mortuary Patterns. This 20-25 male was also accompanied by seven socketed bone projectile points as well. These points, stone and bone alike, probably represent intentional offerings. A second grave, Burial 12, that of a teenage girl contained two Scallorn arrow points, one of which was found during analysis—it was embedded in the third lumbar vertebra. The other point was also found near the spinal column, suggesting that the young woman died a violent death—shot in the back. Chert drills and drill fragments were found with Burial 7 (Initial Late Prehistoric), Feature 82 (Protohistoric), and Feature 65 (Early Historic). Most were fragmentary specimens with the striking exception of the slender chert drill found in Feature 82, a grave containing the secondary burials of an adult of indeterminate gender and a young woman, along with other funerary items including 41 short tubular conch shell beads. As the accompanying illustration shows, the diameter of the drill tip almost perfectly matches the interior diameter of the beads, which were all drilled mainly from one end. Most of the other stone tools came from two Final Late Prehistoric period graves, Features 86 and 87. The most telling stone assemblage is Feature 87, the burial of a 35-39 year-old man who was accompanied by an array of funerary items including inferred shaman-curer’s bloodletting tools (rat teeth set in asphaltum handle and two shark teeth). Clustered around the lower abdomen and pelvis were nine stone tools made of chert including two complete and one fragmentary small bifaces, a small flake scraper, and 12 simple flake tools with use-damaged edges. One of the bifaces had asphaltum adhering to one end, suggesting it had been set within a wooden handle or shaft and may represent a blunt projectile tip of the sort used to kill or stun small mammals or fish by impact. Food OfferingsWhile we would guess that grave offerings and inclusions included organic materials such as leather, plant remains, basketry, feathers, food, and sundry other materials, little direct evidence of organic remains survived except for bone and shell. In the case of Feature 52, the only isolated grave found at Mitchell Ridge, however, there is suggestive evidence of a substantial offering of food. As described in the Mortuary Patterns section, the burial was that of an adult male 30-50 years old who was placed up against the northwest side of the grave pit. In the open area on the opposite side of the pit, was a sizable area of organically stained soil containing hundreds of fish and cotton rat bones. These bones and 14 oyster shells, Atlantic cockle, a small lightening whelk, and a marsh periwinkle very likely represent food offerings. Judging from the diversity of species and the number of individual animals represented by the recovered bone, as well as the size of the dark, organically stained area, a considerable quantity of food was placed in the grave. A radiocarbon assay suggests this interment dates to about A.D. 1300, at the end of the Initial Late Prehistoric period. OchreRed and yellow ochre pigments made from powdered iron oxide minerals such as hematite or limonite, were widely used among prehistoric and historic Native American societies to paint bodies and artifacts, as well as natural surfaces such as rockshelter walls. Ochre masses were documented in only two of the Mitchell Ridge graves, but traces of red ochre were observed on skeletal elements from 18 individuals during osteological analysis. The ochre staining of the bones is very faint in most instances and was not associated with visible ochre or staining in the grave fill around the bones. This suggests that ochre paint was applied to the bodies rather than ochre pigment being deposited as a separate grave offering. Based on the patterning of which bones were stained, osteologist Joseph Powell inferred that the paint was usually applied to the mid-section of the bodies. No correlation with age or sex is apparent, but the incidence of ochre staining appears to increase through time. Ochre staining was found on less than 25% of the Late Prehistoric burials and more than 50% of the Protohistoric and Early Historic burials. Actual masses of ochre pigment in quantities clearly indicating purposeful deposition in the grave rather than painting were found in only two Protohistoric period graves, the secondary token burials in Feature 82, and the primary interment of a young child in Feature 83. The latter had the distinctive concentric pattern of a yellow circle surrounded by a ring of red ochre interpreted as a solar symbol. Glass Trade BeadsA total of 3,243 glass trade beads were recovered from six of the graves in the Area 4 cemetery. Twenty five beads were found with two Protohistoric graves, Features 82 and 83. The remaining beads are from four Early Historic graves, Features 62, 63, 64, and 65 that formed a subcluster on the southern end of the cemetery. All four were large grave pits containing multiple individuals with Features 63 and 64 being the only two graves at Mitchell Ridge that were surrounded by wooden posts many of which were square-hewn. Trade beads are informative artifacts that typify the trading relations between European colonists and Indian peoples in the late 16th through the 18th centuries. European glass beads were manufactured mainly in Venice and the nearby island of Murano in northern Italy since Medieval times. As demand grew for trade items during the colonization of New World in the sixteenth and seventeenth industries, bead making spread to Holland and beads were made in a variety of colors and shapes using several different techniques. American archaeologists have devised several bead classification systems to tease apart the variation and understand their distributions in time and space. The Mitchell Ridge beads were categorized according to the system devised by Jeffery Brain, author of the two-volume Tunica Treasure report based on funerary remains from the Trudeau site near the confluence of the Red and Mississippi Rivers in eastern Louisiana. There massive quantities of trade beads were found in graves of the Tunica tribe dating to 1731-1764. Over 99% of the beads from Mitchell Ridge are of types represented in the Trudeau sample. In the Mitchell Ridge report bead typology and chronology is discussed in considerable detail. It is concluded that the bulk of the trade beads from the site date mainly, if not entirely, to the period of systematic French trade on the Upper Texas Coast and adjacent areas (east Texas and western Louisiana) between 1720 and 1754. While many of the same bead styles were traded by the Spanish, specific characteristics of the Mitchell Ridge bead assemblage are consistent with the ethnohistoric evidence of French-Indian deer skin trade in the region. The beads found at the site could represent down-the-line trade items obtained from Indian middlemen, or direct trade from French traders, such as Blancpain, who established his trading post near Trinity Bay in the middle of the eighteenth century. |

|

|

|

|