|

In this section:

|

The approximate boundaries of the

Lower Pecos archeological region are shown in white

on this shaded relief map. Its southern extent is unknown

but believed to lie in the Burro Mountains of northern

Coahuila. Base map from the Perry-Castañeda Library

Map Collection.

|

|

The rockshelters provide only temporary refuge from

the relentless cycles of the canyon world: night cool

and day heat, drought and flood, bare rock and green

plant.

|

The Pecos River is shallow and mineral-rich.

Its source lies in northern New Mexico, some 685 miles

above its confluence with the Rio Grande. Photo from

ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

Mile Canyon, one of many short, narrow

side canyons that empty into the Rio Grande. The canyon

wall in the far background is across the Rio Grande

in Mexico. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

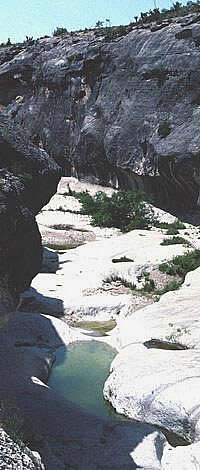

The twisting canyon tunnels form

a closed-in world framed by white-rock walls and the

blue sky high above. Sound, water, and critters travel

through the canyon tunnels, seeking each other and

the hidden green pools of water—tinajas. Photo

by Steve Black.

|

Seminole Canyon. In the background

the canyon floor has been scoured by flood, in the foreground

stacked up boulders trap soil and moisture and provide

shelter for trees and shrubs. Photo by Steve Black.

|

Greasewood flat. Creosote bush or

greasewood, is typical of the Chihuahuan Desert. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

Small seep springs like this one

can be found in many of the canyons.

Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

|

Although the Lower Pecos Canyonlands

occupies only a small part of Texas, its natural world is far from uniform. It is, in

fact, a place marked by contrast: green and brown, canyon

and upland, one river and the next, yesterday and today. This

section introduces the natural world through

pictures and words.

The Lay of the Land

The Lower Pecos Canyonlands lies at the southwestern

edge of the Edwards Plateau—the Texas Hill Country as

most know it—which in turn lies at the southern edge

of the Great Plains. It also is within the northeastern edge

of the Chihuahuan Desert. The area is located along

the middle part of the Rio Grande drainage basin just below

the S-shaped "Big Bend" where the river turns southward

toward the Gulf of Mexico. It is there that the Rio Grande

is joined by the last two major streams that feed its middle

and lower stretches—the Pecos River, and the Devils River.

And it is the juncture of these three rivers that forms the

core of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands.

Within the region, the Rio Grande embankment

is dissected by precipitous canyons and arroyos that enter

the river on both sides. North of the Rio Grande, the land

is level to hilly and is cut by numerous canyons. South of

the Rio Grande lies an extensive plain broken by intermittent

streams that originate in the Serranias de los Burros, a mountain

range rising to almost 5,000 feet (1,524 meters). These mountains

parallel the Sierra del Carmen of Mexico and the southern

escarpment of the Edwards/Stockton Plateau. The southern part

of the Burros are dominated by the 4,700-foot-tall Cerro Oso

Blanco (White Bear Peak), which is located about 70 kilometers

(43 miles) southwest of Del Rio.

The deep canyons and porous limestone geological

formations of the region give rise to numerous permanent or

temporary streams and springs that stand in contrast to the

xeric (desert-like) nature of the plains and plateau country

that they dissect. The three permanent streams—the Rio

Grande, the Pecos River, and the Devils River—are the

life blood of the region, providing water and refuge to plants,

animals, and people. The Pecos River enters the Rio Grande

just 26 miles (42 kilometers) northwest of the confluence

of the Rio Grande and the Devils River. All three major streams

are joined by numerous small intermittent streams that form

narrow side canyons and break up the surrounding topography

into ridges, mesas, and fingers overlooking the deep green

winding worlds of the rivers.

The uplands and canyons

really are two worlds that make one. Upon the uplands the

horizon stretches forever, a jagged purple-blue line that

slowly fades to black at dusk. Up on top, the wind sculpts

squinting faces, sets ceniza and ocotillo branches to dancing,

and fuels the rusty silver flash of a well-oiled windmill.

There is no lasting natural reprieve from the relentless sun;

the trees are small and dark clouds all too infrequent. In

the best of times, the upland flats are grassy plains that

once lured herds of buffalo down from the north. In the worst

of times, there is nothing but thorn, rock, and dust.

And down below, the twisting canyon tunnels

form a closed-in world framed by white-rock walls and a blue

sky high above. Sound, water, and critters travel thorough

the canyon tunnels, seeking each other and the hidden green

pools of water. The tenacious roots of sheltered trees try

to hold the canyon floor together. But in time, each scene

changes as canyons become half-choked with washed-in soil

and the plant life that gladly follows, only to be scoured

clean by a once-in-three-lifetimes deluge. The rockshelters

provide only temporary refuge from the relentless cycles of

the canyon world: night cool and day heat, drought and flood,

bare rock and green plant. They, too, crumble with time.

Many large springs are located within and adjacent

to the Lower Pecos Canyonlands due to its location at the southwestern

edge of the Edwards Plateau. These springs occur mainly along

the Balcones fault zone where underground rivers (aquifers)

come in contact with impervious geological formations, forcing

the water to escape to the surface under artesian pressure.

Just east of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands, San Felipe Springs are

the fourth largest springs in Texas and still serve as the

sole source of water for the city of Del Rio. Goodenough Springs,

also one of the largest springs in Texas, is located beneath

the waters of Amistad Reservoir in a side canyon of the Rio

Grande. Although surface water was confined to narrow canyons,

numerous springs also existed on the plains to the south of

the Rio Grande. The abundance of permanent streams and springs

means that water was seldom a limiting factor to travel.

The Modern Climate

The southern and western edges of the Lower

Pecos region receive an annual average of as little as 10

inches of rainfall, while the northeastern edge averages almost

19 inches per year, figures which place the area within a

semi-arid climatic zone. Most precipitation occurs in two

peaks, one in spring (April-May) and one in early fall (September-October),

both fueled by thunderstorms at frontal boundaries fed by

moisture from the Gulf of Mexico and sometimes the Pacific.

The heaviest, drought-busting rains occur when tropical storms

stall over the area, sometimes dumping devastating, canyon-scouring

quantities of rain in a matter of hours or days. The driest

months of the year occur in winter from November to March,

and in summer from June to August. The frost-free period averages

300 days between February 13 and December 8. The average annual

temperature is 70ºF, ranging from a low of 51ºF

in January to a high of 86ºF in July.

Although these averages give a general impression

of climate, the truly interesting aspect of southwestern Texas

climate is its variability. The Lower Pecos Canyonlands region is positioned

at two great climatic crossroads of the North American continent—along

the sharp line between the humid east and the arid west, as

well as the more ambiguous divide between the markedly seasonal

regimes to the north and the winterless tropical climes to

the south. Consequently, the region encompassing southern

Texas and northeastern Mexico has a semiarid, subtropical

climate with dry winters and hot summers. More critically,

the climatic region containing the Lower Pecos has a greater

degree of year-to-year rainfall variation than any other semiarid

region in the world, except for northeastern Brazil. Rainfall

is highly unpredictable and drier-than-normal years are much

more common than extremely wet years.

In short, the Lower Pecos Canyonlands lies within a climatically

transitional region that can shift from a relatively well-watered

green and grassy place to a dusty brown desert in a matter

of years or even months. It is a marginal region for intensive

land use—plant and animal populations are quickly affected

by fluctuations in precipitation. Throughout its history,

humans have had to cope with climatic uncertainty, savoring

the good months and years and suffering the many bad ones.

Vegetation

Mirroring the terrain and climate, the Lower

Pecos lies within a major transition zone where three great

biotic provinces converge. To the southeast is the mesquite

and thorn brush savannah of the South Texas Plains. To the

north, the vegetation grades into the juniper-oak savannah

associated with the Edwards Plateau, while Chihuahuan Desert

Scrub covers the core area of the lower canyonlands of the

Devils River, the Pecos River, and the Rio Grande and farther

south.

Overall, the Lower Pecos area is a savannah with

a mix of grasses, brush, and trees. Depending on the local

conditions, the area may favor shrubs or grasslands. The southeastern

edge of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands is part of the mesquite-acacia

savannah of southern Texas. To the west, vegetation rapidly

grades into sotol-lechuguilla-creosote bush vegetation typical

of the Chihuahuan Desert. Despite the fact that the region

is technically a savannah, woody plants dominate the vegetation

in most upland areas within the boundaries of the reservoir

today. These include mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa),

several species of acacia (Acacia spp.), whitebrush

(Aloysia gratissima), Texas persimmon (Diospyros

texana), blue sage (Salvia ballotiflora), lotebush

(Ziziphus obtusifolia), various buckthorns (Condalia

spp.), and spiny hackberry (Celtis pallida). Creosote

(Larrea tridentata) and ceniza (Leucophyllum frutescens)

are prominent in many areas. Along the upper reaches of canyons,

succulents and rosette-stemmed evergreens are also common,

including prickly pear and tasajillo (Opuntia spp.),

several yuccas (Yucca spp.), and Agave lechuguilla.

Small trees are confined to narrow canyons or creek terraces.

Littleleaf walnut (Juglans microcarpa), several species

of oak (Quercus spp.), Mexican ash (Fraxinus greggii),

and Texas persimmon (Diospyros texana) are a few of

the more prominent tree resources located in the canyons.

Large stands of Huisache (Acacia farnesiana) and mesquite

(Prosopis glandulosa) occur on certain of the broad

terraces in the eastern part of the region.

Paleoenvironment

Despite the remarkable detail of the prehistoric

vegetation record contained in numerous, well-preserved rockshelter

deposits, only the general outline of the environmental history

of the Lower Pecos is known well. It appears that the Chihuahuan

Desert has expanded and contracted throughout the late Pleistocene

(prior to 9,000 B.C.) and Holocene (or Recent) periods, leaving

widespread relict populations of certain plants in favorable

microenvironments such as the protected and relatively well-watered

canyons. This is critical for two reasons. First, prehistoric

peoples often relied on these relict or stranded populations

of plants that are otherwise not commonly available in the

area. Second, the mix of local and relict plant communities

makes it difficult to reconstruct past environments because

all but the most drastic vegetation changes are masked in

the archeological deposits.

The general climatic trends can be seen in the

pollen record. As allergy sufferers know only too well, during

certain times of the year certain plants release large amounts

of pollen. Some of this pollen rain survives, especially in

permanently wet places like swamps and in very dry places

like the rockshelters of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. By studying samples

from deposits of known ages, pollen experts have reconstructed

the paleoenvironment of the region at least in broad terms.

Decreasing frequencies of pine pollen indicate that the region

was slowly drying throughout the Holocene, with a brief wet

interval occurring around 2,500 years ago marked by an increase

in pine and grass pollen frequencies.

While pollen provides a very general view of

regional vegetation, most of what is known about Lower Pecos Canyonlands

vegetation has been gleaned from the analysis of plant remains

found in archeological deposits in the dry caves and rockshelters.

The best known shelter in the Lower Pecos area is

Hinds Cave which was excavated by archeologists from Texas

A&M in the 1970s. The Hinds Cave work showed that plants

common in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands today, including lechuguilla (Agave

lechuguilla), yuccas (Yucca torreyi and Y. rostrata),

sotol (Dasylirion texanum), acacias (Acacia greggii

and A. rigidula), prickly pear (Opuntia phaeacantha),

shin oak (Quercus pungens var. vaseyana), mesquite

(Prosopis glandulosa,) and juniper (Juniperus spp.),

were well established in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands by 7000 B.C.

|

In its lower reaches, the Pecos River

carved a deep canyon entered by many side canyons. This

photo was taken during the 1966 excavations at Arenosa

Shelter, which is visible in the center of the picture.

Today this area is choked by massive silt deposits that

have built up since Amistad Reservoir was formed. Photo

from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

Click images to enlarge

|

The lower Devils River prior to the

construction of Amistad Reservoir. Although much shorter

than the Pecos and the Rio Grande, the Devils River

is spring fed and its waters are clear and "sweet"

compared to the often muddy and salty waters of the

other two. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

Numerous springs issuing out of the

Edwards Aquifer feed the Devils River. Photo from ANRA-NPS

Archives at TARL.

|

Spring-fed tributary of the Devils

River. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

Innumerable canyons like this one

provide shelter for plants, animals, and humans. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

|

Throughout Lower Pecos history, humans have had

to cope with climatic uncertainty, savoring the good

months and years and suffering the many bad ones.

|

Many of the deeply incised canyons

are lined by cliffs, their walls so steep that they

are all but invisible until you are almost standing

on the canyon edge. Viewed from the air, the canyons

form tree-like patterns with the rivers as trunks and

the smaller streams and side canyons forming limbs and

branches twisting and turning across the land. Photo

by Steve Black.

|

An archeological survey team gathers

on this upland area. Standing in the middle of one of

the flat upland areas between the canyons, it looks

as though vast unbroken plains stretch in every direction.

Yet less than a hundred yards away is a deep canyon.

Photo by Steve Black.

|

Prior to the introduction of sheep,

goats, and cattle, the upland areas of the Lower Pecos

Canyonlands had extensive grasslands like this restored area. During

wet climatic intervals, the grasslands flourished and

herds of buffalo migrated into the area. During one

such interval about 2800 years ago, hundreds of buffalo

were driven off the cliff above Bonfire Shelter. Photo

by Phil Dering.

|

Flower-painted uplands after a wet

winter. Photo by Steve Black.

|

The towering flower stalks of the

sotol plant are a common sight in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. Sotol

prefers thin rocky soils and steep terrain and often

grows in great abundance in such areas. Prehistoric

peoples harvested sotol hearts or "cabezas"

(heads) in quantity and baked them in earth ovens. Photo

by Phil Dering.

|

|