Caddo Homeland: the Land and its Resources

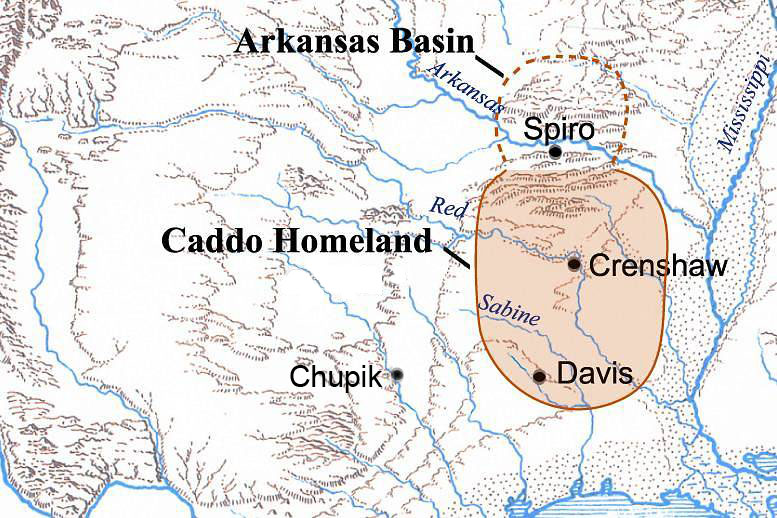

| The historically known Caddo and their direct ancestors appear to have lived in the same area for over 3,000 years, perhaps even 4,000 years or longer. This statement is based on linguistic inferences reviewed in Caddoan Languages and Peoples, on extensive archeological evidence (see Caddo Ancestors), on the observations of early European explorers, and, to some extent, on Caddo oral tradition. The main Caddo Homeland, as we will call the area throughout the Tejas exhibits, stretched for about 300 miles (480 kilometers) north-south and 220 miles (355 kilometers) east-west, a vast territory of about 51,830 square miles (134,235) square kilometers) within which over 150 generations of Caddo peoples lived and died. The coming of the Europeans and their germs, guns, horses, and ambitions severed a truly remarkable long-term relationship between a people and their land. All of the historically known groups who spoke dialects of the Caddo language lived within the main Caddo Homeland as we see it here. The Caddo Homeland may have once stretched northward into the Arkansas Basin as far as the southern Ozarks in northwestern Arkansas and southernmost Missouri. While archeologists have long referred to this area as the "Northern Caddoan Area" the ethnic identity of the people of Spiro and its hinterland is debated. If the prehistoric people of that area were among the ancestors of the modern Caddo, they had abandoned the area and moved southward by the 16th or early 17th century, if not before. Alternatively, the Arkansas Basin may have been home to the ancestors of the speakers of one of the Northern Caddoan languages (Kitsai or Wichita) or even, as has been suggested, to a completely unrelated ethnic group, the Tunica. The map above shows the Arkansas Basin in dashed line to indicate the continued uncertainty. See Spiro and the Arkansas Basin for a more complete discussion. Caddo Homeland DescribedThe greater Caddo Homeland (including the Arkansas Basin) can be explored through the interactive Caddo Map Tool. Here we provide an overview of the area and discuss certain points not accessible through the map tool. Many of the images shown here can also be accessed through the map tool, which also contains many other images. The main Caddo Homeland lies south of the Arkansas River valley and is roughly bounded on the north by the northern flank of the Ouachita Mountains and on the west by the Blackland Prairie. These are ecological boundaries, not physical barriers. Likewise, the southern boundary seems to coincide with the belt of deep sands that flanks the inner edge of the Gulf Coastal Plain. These sands are not productive for agriculture and effectively prevented the Caddo from expanding to the south. To the east is the Lower Mississippi Valley. Whether bounded by natural features or not, the edges of the Caddo Homeland would have been defined, in part, by the presence of non-Caddo groups. To the north of the main Caddo Homeland is the Arkansas Basin area, which includes the Arkansas River Valley from western Arkansas into eastern Oklahoma and adjacent areas mainly to the north. Archeological sites thought to be related to the Caddoan tradition are found a short distance west of Spiro out into the Cross-Timbers and Bluestem Prairies along the Arkansas River and its westward and northward tributaries, including the Canadian, Grand, and Neosho rivers. Also included is the southern part of the Ozark Highlands including the Boston Mountains, which provide some of the greatest topographic relief found in the region. This part of the Ozark Highlands has relatively small streams and rivers that drain southward or westward into the Arkansas and Grand rivers, as well as the upper part of the White River drainage, which flows to the northeast. Returning to the main Caddo Homeland, the landscape of its northern part is dominated by the Ouachita Mountains. Streams and rivers in the north are relatively fast-running and clear and flow within narrow valleys. The broad valley of the upper Ouachita River is an exception. South of the Ouachita Mountains, the Caddo Homeland is a gently rolling terrain dominated by forests interrupted only by rivers flowing eastward or southeastward toward the Mississippi or south toward the Gulf of Mexico. With minor exception, the entire Caddo Homeland is forested, although today the forests are highly fragmented and all areas with productive soils have been cleared for agriculture or pasture at one time or another. The often-broad river valleys provided flat bottomland expanses with fertile soils that were favored by Caddo farmers. Within the Ouachita Mountains, the Ouachita River has numerous tributaries, including the Caddo and Little Missouri rivers. Another tributary, the Saline River lies farther east beyond the Ouachita Mountains and is the easternmost drainage reached by ancient Caddo settlement. Numerous streams and small rivers draining the southern and southwestern flanks of the Ouachitas flow southward and join the Red River including the Little and Kiamichi rivers. The Kiamichi River is notable because its narrow valley was a natural transportation route between the Red River Caddo and Spiro. Unlike almost all other drainages in the Caddo Homeland, the Kiamichi flows west before turning south to join the Red River. The Red River is the central feature of the Caddo Homeland and its largest river. Throughout Caddo history and prehistory, the Red River valley from Lamar County, Texas to just below Natchitoches, Louisiana, was the setting for many of the most impressive cultural developments, including many of the earliest, largest, and latest villages and ceremonial centers. The wide Red River floodplain is dissected by meander scars marking abandoned channels where the river once flowed. These abandoned channels often become oxbow or "cutoff" lakes, and rich sources of aquatic resources. The floodplain was ideal for Caddo farmers, offering natural clearings and deep, rich soils in stark contrast with the poor upland soils of the adjacent forests. In many ways the Red River was the heartland of the ancient Caddo world. Initially, this was, in part, because the Red River linked the Caddo Homeland with the lower Mississippi Valley (LMV) to the southeast and the prairie-plains to the west. The Red River is, in fact, the last (southernmost) western tributary of the mighty Mississippi. The confluence of the Red River and the Mississippi figured prominently throughout the very long cultural history of the LMV. In particular, several of the largest and most important Middle Woodland centers of Marksville culture (200 B.C. to A.D. 500) were located at the ancient confluence of the Red River and Mississippi. This is worth noting because the Marksville culture seems to have influenced Woodland cultures in the Caddo Homeland. But by around A.D. 1000 or shortly thereafter, the Red River was blocked by the initial formation of the massive logjam known in historic times as the Great Raft. This raft built up over the next 800 years. In the early 1700s, a French trading party led by La Harpe needed 26 days to travel 108 leagues (298 miles) by canoe from Natchitoches to the mouth of the Sulphur River. The blockage of this natural transportation route at about the same time that the distinct Caddo cultural tradition developed (ca. A.D. 1000), probably helps explain why there is comparatively little evidence for extensive interaction between the LMV peoples and Caddo peoples during the Mississippian period. In northeast Texas, south and west from the Red River, Caddo groups lived in and near the valleys of the many rivers and streams. From north to south the main drainages include the Sulphur River, Big Cypress Creek, the Sabine River, the Neches River, and the Angelina River. Bottomland plant communities along these watercourses included hardwood and swamp forests, with natural levees, point bar deposits, old stream channels, oxbow lakes, and backwater swamps forming diverse environments and natural resources. Northeast Texas has three main biotic communities: the Post Oak Savanna or Oak Woodlands, the Blackland Prairie, and the Pineywoods. The Caddo lived mainly within the modern distribution of the Pineywoods and the Post Oak Savanna, occasionally traveling west beyond the tall-grass Blackland Prairie to hunt bison. (Buffalo eat short grasses.) The Post Oak Savanna is a narrow southwest to northeast trending woodland belt that marks a natural transition zone or ecotone between the drier Blackland Prairie to the west and the moister Pineywoods to the east. Both the Post Oak Savanna and the Pineywoods have medium-tall to tall broadleaf deciduous forests, and shortleaf and loblolly pines are common in the Pineywoods on upland fine sandy loam soils with adequate moisture. Small areas of tall grass prairie may be present in both communities throughout the region. The southwestern Caddo Homeland is the only area that is not part of the Red River and Mississippi drainage system. The Sabine, Neches, and Angelina rivers are part of the Sabine watershed. The Sabine empties into the Gulf of Mexico almost 300 miles west of the mouth of the Mississippi. The Neches and Angelina river valleys were occupied in Woodland times by the Mossy Grove culture, whereas the Fourche Maline culture flourished along the Red River and its many tributaries. By A.D. 800, Caddo groups appear to have moved into the upper and middle Sabine drainage. It is not clear whether the Mossy Grove peoples were displaced or assimilated (or both) into Caddo culture. During the early historic period, the southeastern Caddo Homeland was the territory of the Hasinai Caddo groups, while to the south were non-Caddo groups such as the Bidai, Atakapa, and Ais, who may represent the descendants of Mossy Grove culture. Throughout the history of humankind, rivers have been the focal point for many cultures and civilizations. The mere mention of rivers such as the Tigress and Euphrates, the Nile, the Danube, and the Amazon conjures up images of the distinct cultures that arose along side them. Although less well known, the Caddo, too, were intimately linked to the rivers and streams of the Caddo Homeland. Much of Caddo life revolved around the rivers and streams along which they usually lived. The watercourses provided sustenance and floodplain settings for farming; the larger streams and rivers also served as water-borne transportation corridors. River and stream bottoms also provided habitat for a diverse range of useful plants and critters not found in the surrounding pine and oak forests. Although most of the Caddo region was (and still is to a lesser extent) heavily wooded and dominated by pine or oak-hickory forests, the Caddo lived on the edge. As a farming people, the Caddo sought out natural breaks in the trees rather than trying to clear large areas of the primary forests as Euro-American settlers and their modern descendants have done. Lacking metal tools, the Caddo found it easier to take advantage of natural breaks and edges and slowly enlarge these with traditional tree-felling methods. Stone axes are effective tree-cutting instruments, but the process is slow and labor-intensive. You can see why the Caddo sought out natural breaks such as those along the streams and rivers that were caused by major floods. Other common localities for settlement were natural (and man-made) prairies, which occur as major landscape features along the western edge of the Caddo Homeland as well as small, isolated "pocket" prairies that occur within the forests south of the Ozarks. Some of the pocket prairies within the forests probably began as natural features, but others were almost certainly man-made clearings created and maintained by the Caddo through regular burning. Such openings would have been necessary for farming and, perhaps critically, to provide the large quantities of tall grass that the Caddo needed for the thick thatch roofs of their houses. Accounts from the 18th and early 19th centuries describe pocket prairies along the Red River as grasslands sometimes a mile or more in extent with scattered shrubs and bois d'arc trees. These are not like the extensive Blackland Prairies located on the western edge of the Caddo Homeland and found in smaller remnant patches such as those along the Little River in southwest Arkansas. Early Anglo settlers often encountered long-abandoned Caddo settlements on the edges of prairies and gave them names such as "Mound Prairie" and "Caddo Prairie." Battle Mound, the largest earthen mound constructed by the Caddo, was located near Chickaninny Prairie, a name that is derived from the Caddo word "Chakanina" meaning "the place of crying." This place name figures prominently in several of the origin stories told by the Cadohadacho in the 19th century. Within the main Caddo Homeland, the area with the richest mineral and rock deposits prized by the Caddo is the Ouachita Mountains. Artifacts made of novaculite, flint, quartz, shale, sandstone, and various other metamorphic rocks from the Ouachitas are found in Caddo sites hundreds of miles to the southeast. Some minerals, especially clay and hematite (red ochre), but also sandstone and fossilized wood, do occur widely in the non-mountainous areas of the homeland. As you go south into the Gulf coastal plain, rocks and minerals are scarce. The climate of the Caddo Homeland is classified as subtropical humid, meaning that it is relatively warm and wet and has relatively long growing seasons and hot summers. But there are significant climatic differences across the region. Most rain falls in the spring and fall. The average annual rainfall increases west to east from below 35" on the western edge to 51" on the eastern edge and even higher in eastern parts of the Ouachita Mountains. Average temperature increases north to south from 61.5 F in the Ouachitas to 67 F at the southern edge of the Caddo Homeland. Most critically, the average number of frost-free days ranges from less than 200 in the higher parts of the Ouachitas to more than 250 in the southern part of the region. For the Caddo, this meant that groups living south of the Ouachitas could harvest two corn crops per year, a decided advantage to people who depended on corn. Droughts are not uncommon, and tree ring data for the last 1000 years suggest there were numerous prolonged wet and dry periods lasting years or even decades. Dry conditions and the worst droughts occurred in the late A.D. 1200s, in the mid-1400s and 1600s, and then again in the mid-1700s. The period between A.D. 1549-1577 is thought to have had the worst June droughts (a critical period for corn farmers) in the past 450 years. Another significant drought period occurred between ca. A.D. 1450-1490. More favorable crop growing conditions probably occurred during the intervening years, especially between ca. A.D. 1390-1440, then in the latter part of the 16th century and early 17th century, and finally, at the beginning of the 18th century when Spanish and French colonists settled among the Caddo peoples in earnest. These climatic fluctuations would have affected the predictability and success of the maize harvests and impacted the histories of Caddo communities, especially those living in the drier western half of the Caddo Homeland. |

||

|

The coming of the Europeans and their germs, guns, horses, and ambitions severed a truly remarkable long-term relationship between a people and their land. |

The Caddo "lived on the edge." As a farming people, the Caddo sought out natural breaks in the trees rather than trying to clear large areas of the primary forests as Euro-American settlers and their modern descendants have done. |

|