These two circular stone alignments

were partially exposed by riverbank erosion at the Chicken

Creek site within the Lake Meredith National Recreation

Area. Archeologists from the Bureau of Reclamation completely

exposed the patterns, which are thought to represent

the wall foundations of small structures, perhaps seasonal

field houses. The National Historic Preservation Act

of 1966 has given archeologists the opportunity to carry

out research at many small, unimposing Antelope Creek

sites that earlier archeologists overlooked. Photo by

Beverly Couzzourt, courtesy US Bureau of Reclamation.

Click images to enlarge

|

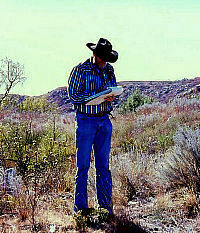

Landowner John Erickson and archeologist

Doug Boyd examine traces of a pit associated with a

Plains Village site. Excavations in 2004 revealed a

bowl-shaped barrow pit filled with household debris

including burned corn. Erickson's keen interest in the

ancient history of his ranch in northern Roberts County

has resulted in an ongoing research project involving

professional and avocational archeologists. Photo by

Steve Black.

|

Cover of a report on the Black Dog

Village site. This project by the Texas Department of

Transportation was one of the first Antelope Creek excavations

undertaken because of the National Historic Preservation

Act of 1966.

|

Mesa Alamosa is a smaller version of Landergin Mesa

some five miles to the east, and is sometimes called

“Little Landergin Mesa.” It, too, may

be a defensive retreat position used by Antelope Creek

villagers during periods when hostile raids were expected.

Mesa Alamosa was known to Studer and Hughes, but was

first formally recorded by Marmaduke and Whitsett

in 1973. Photo by Chris Lintz.

|

Excavations underway at the Chicken

Creek site in the winter of 1983 to salvage information

about this small Antelope Creek site before it was destroyed

by erosion. Photo courtesy U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

|

|

One of the enduring

problems in archeology is that it is often very difficult

to find adequate funding for the final and, ironically,

most important part of any research project—the

hard work of thoroughly analyzing the recovered materials

and fully reporting the results.

Fortunately, most cultural resource management projects

include contractual requirements to fully complete the

archeological work. The resulting technical reports

that are part of what is often called the vast “gray”

literature. While such reports are not intended for

a public audience, they are an essential part of the

cultural resource management process.

|

Archeologists perched atop Landergin

Mesa during the 1984 excavations sponsored by the Texas

Historical Commission. Photo courtesy Chris Lintz and

the Texas Historical Commission.

|

Aerial view of the 1984 excavations

underway at Landergin Mesa during work sponsored by

the Texas Historical Commission. Antelope Creek villagers

had retreated here in times of conflict. While the steep

walls flanking the mesa top once made the site easy

to defend, it also made archeological access a challenge.

Photo courtesy Chris Lintz.

|

The 1969 TAS field school investigated

several Antelope Creek sites along Blue Creek, a tributary

of the Canadian River, on National Park Service property

near Lake Meredith. Photo by Wallace Williams.

|

Pithouse excavated in August 2003

in the Buried City settlement zone by a field school

of the University of Oklahama. The work is part of Scott

Brosowske's dissertation research. Photo and graphic

by Brosowske.

|

Graduate Student Contributions

Graduate students have completed many

worthwhile studies on Plains Village topics related

to the Texas Panhandle. Here are some additional examples.

In the 1930s, E.J. Lowrey

and Tom Holden, two of Currie Holden’s

students from Texas Technical College completed graduate

theses on excavations at Antelope Creek 22, and the

pottery of Saddleback Ruins, respectively. More recent

contributions ... read

more>>

|

Archeologist Glenna Dean points to

the original base of a mesquite tree, which sticks up

some three feet above the modern ground surface near

Landergin Mesa. Long-term drought and overgrazing has

caused massive erosion during the last century in some

areas of the Texas Panhandle. Drought cycles plagued

the Plains villagers as well, although they did not

have to cope with overgrazing; in dry periods bison

moved elsewhere or died off. Photo by Chris Lintz.

|

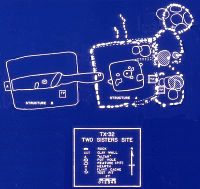

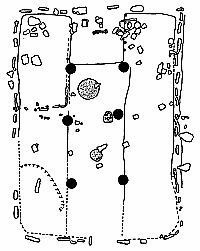

Plan map of two rectangular houses

at the Two Sisters homestead in the Oklahoma Panhandle

that are thought to represent successive occupations

by a single Plains Village family. The simple rockless

house on the left (Structure B) was succeeded by a more

elaborate house (Structure A) with a typical Antelope

Creek style stone slab foundation and smaller, attached

circular rooms. Graphic, courtesy Chris Lintz.

|

Structure B, the earliest of two

rectangular houses at the Two Sisters site, had most

of the architectural elements of a typical Antelope

Creek house, except the stone slab foundation. (Instead,

it probably had picket-post walls). Photo by Chris Lintz.

|

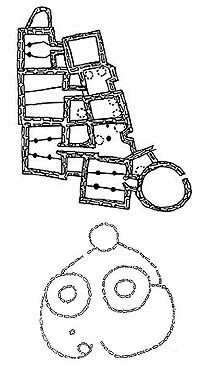

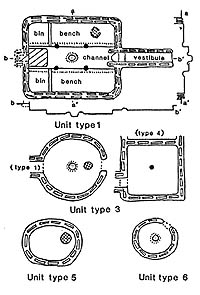

Antelope Creek vs. Apishapa

architecture. At top is the plan of main room

block at Alibates 28. The circular Apishapa pattern

is from the Cramer site in southeast Colorado. Both

are shown are roughly the same scale. Courtesy Chris

Lintz.

|

Chris Lintz excavating one of the

storage pits beneath Structure 5A at the Two Sisters

site in 1973.

|

This 1986 report by Chris Lintz is

the published version of his 1984 University of Oklahoma

dissertation. It is one of the more useful studies of

Antelope Creek culture that has ever been done.

|

Lintz devised a detailed typology

of Antelope Creek structures and storage pits (collectively

termed architectural "units") to compare these

systematically from site to site. Lintz 1986, Figure

10. Click to see full graphic.

|

The Tucker Blowout site in the Oklahoma

Panhandle is a buffalo kill and butchering site that

dates to the fifteenth century. It is believed to be

the work of late Antelope Creek villagers or their immediate

descendants. Given the high frequency of buffalo bones

in many Antelope Creek villages, there must have been

many such butchering and kill sites. Photo by Chris

Lintz.

|

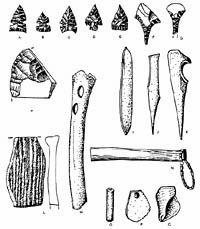

Antelope Creek phase artifact assemblage.

Click on image to see details. From

Lintz 1986, Figure 4.

|

Fragment of a charred basket found

on the floor of a burned Antelope Creek house. Antelope

Creek villagers were probably excellent basket makers,

but very few of their baskets survived. This one was

preserved only because it was intensely burned. PPHM

collections, photo by Steve Black.

|

Doug Wilkens introduces a visiting

group of homeschooled kids and their parents to the

Indian Springs archeological site in Roberts County.

Wilkens is an active avocational archeologist as well

as one of the Texas Historical Commission's archeological

stewards. Dedicated volunteers continue to play a huge

role in Panhandle archeology. Photo by Steve Black.

|

|

Since the 1960s, archeologists studying the

Plains village sites of the Texas Panhandle and adjacent regions

of the Southern Plains have struggled mightily to make sense

of the variation that they and their predecessors have encountered.

We have come to realize that Antelope Creek culture was a

lot less uniform than earlier archeologists had believed.

As is invariably the case with ancient cultures, the more

we learn, the more we realize we still don't know.

Earlier archeologists were drawn to the larger

"villages," like Antelope Creek 22 and Alibates

28, that had visible structures arranged into pueblo-like

blocks of houses. These now appear to be the exception rather

than the rule. Even the larger Antelope Creek "villages"

would have been home to only a few dozen people and could

be more accurately called hamlets. These

paled in comparison to the truly large, fortified prehistoric

and historic villages in the Central and Northern Plains within

which hundreds of people lived. In contrast, most Antelope

Creek people seem to have lived in family groups in small

hamlets and even smaller farmsteads with

only one or two houses.

Instead of a single tribe or ethnic group of

closely related people, archeologists have found increasing

evidence that various Plains Village groups co-exisited in

different portions of the area we know today as the northern

Texas Panhandle. It is still likely that most of the core

area of the Antelope Creek culture along the Canadian River

valley north of Amarillo was home to villagers who were closely

related to one another, genetically and culturally. But not

so far away there were other peoples, such as those who lived

at Buried City, who probably belonged to different groups

or tribes and perhaps spoke different languages (or at least

different dialects). Increasingly, archeologists have found

evidence of competition and conflict among Plains villagers

and, perhaps, other less-settled peoples who found the villages/hamlets

to be tempting targets.

In this section we try to summarize the last

40 years or so of archeological research in the region, knowing

full well that there isn't any easy way to do this. Archeology

is a lot more complicated today and involves many more people

than it did in Floyd Studer's day.

CRM Archeology

Since the mid-1960s American archeology has

been transformed by the impact of federal and state laws intended

to protect cultural resources such as the National

Historic Preservation Act of 1966 and the Texas

Antiquities Code of 1969. These laws require that

archeological and historical sites on government land, and

on private land being developed or disturbed with federal

funding or by federal permit, be studied and evaluated before

adverse impacts are allowed to take place. If an important

archeological site lying in harm's way cannot be avoided and

protected, then research is carried out through excavation

or other means to preserve some of the information that makes

the site important, thus “mitigating” the loss

of information that the development will cause. One result

of these laws has been a tremendous increase in funding for

archeology and in the number of professional archeologists

employed by universities, government agencies, and, increasingly,

private industry. The industry that has developed because

of state and federal historic preservation laws is called

cultural resource management or CRM archeology.

Compared to many other areas of the country

and the state, the northern Texas Panhandle has seen only

a modest increase in the amount of professional archeological

research in recent decades. Most of the land remains in private

hands and population densities remain comparatively low in

most areas, hence federally or state regulated developments

are few. Nonetheless, cultural resource laws have led to new

research in the Antelope Creek area, especially on federally

owned lands in the general vicinity of Lake Meredith including

the Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument, the Pantex

Ammunitions Plant, and the Exell Helium Plant at the Cross

Bar Ranch. Although some excavations have taken place, efforts

to locate and evaluate archeological sites on federal lands

have resulted in a better understanding of the settlement

patterns of Antelope Creek villagers. Small hamlets and isolated

farmhouses were, we now know, much more common than the larger

pueblo-like ruins that attracted so much archeological and

public attention for so long.

In 1973, William Marmaduke

and Hayden Whitsett conducted an archaeological

reconnaissance in east Oldham County in the western part of

the Panhandle as a contribution to a “Natural Area Survey”

of the Canadian Breaks. This state-funded project recorded

49 archeological sites along Alamosa Creek and formally documented

Landergin Mesa and Little Landergin Mesa, both important Antelope

Creek sites. The resulting report highlighted the potential

of the region’s natural and cultural resources to be

protected and developed into regional attractions such as

state parks.

Federally funded highway work in the early 1970s

led to the excavation of part of the Black Dog Village

site, a large Antelope Creek settlement located at the confluence

of Cottonwood and Tarbox creeks with the Canadian River north

of Borger. Professional archeologists with the Texas Highway

Department excavated five structures there, aided by Jack

Hughes, Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum personnel, and volunteers

from the Panhandle Archeological Society. While a large Antelope

Creek structure dubbed the “Big House” attracted

much attention, two pairs of small rooms lacking typical Antelope

Creek house features were found that probably represent later

occupations.

During the 1970s, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation

conducted a number of archeological surveys at Lake Meredith.

Archeologsits revisited the known sites and searched for unrecorded

sites around the lake in order to assess (and lessen) impacts

from public land use activities. Archeologists Meeks

Etchieson and Jim Couzzourt surveyed

the shore line during periods when the lake level was low

and recorded 53 sites, few of them known from the earlier

1961 survey. They also excavated slab-lined pits at two sites

and conducted flotation and radiocarbon dating on the contents

of these pits. Etchieson, a fulltime employee of the Bureau

of Reclamation, also conducted other small surveys and damage

assessments of tracts around the lake that were being impacted

by off-road vehicle traffic. This led to the “salvage”

excavation of several Antelope Creek houses. The results of

such work are documented in technical reports that are part

of what is often called the vast “gray” literature.

While such reports are not intended for a public audience,

they are an essential part of archeological research.

Etchieson was also instrumental in using archaeology

as a training program and involved the Youth Conservation

Corps in the testing and excavation of several sites at

Lake Meredith. These include the South Ridge site, the Ozier

site and a site on Plum Creek. The South Ridge site was used

during Antelope Creek times and earlier periods as well and

has been reported in full detail. The excavations at the two

other sites were supervised by Etchieson and other archeologists,

but have never been properly reported. It is difficult to

complete research during training programs such as these,

because they are geared chiefly toward excavation and preliminary

artifact processing, not full analysis and reporting. This,

of course, was the same problem faced by the WPA in the 1930s

and early 1940s.

In 1982-83, the National Park Service and the

Bureau of Reclamation funded two seasons of excavations at

the Chicken Creek site. Riverbank erosion

threatened this Antelope Creek site, where two small circular

structures were found. The fieldwork was directed by Beverly

Couzzourt, but the detailed results from only the

first season have been reported.

In 1990, all lands at Lake Meredith, except

some 700 acres of the dam axis and anchoring bluffs, were

transferred from the Bureau of Reclamation to the

National Park Service (NPS) jurisdiction. The changes

in federal responsibilities have sparked more interest in

surveys at Lake Meredith. Archeologists from the NPS Southwestern

Regional Office have carried out evaluative testing on several

Antelope Creek sites at Lake Meredith. Various private consulting

firms have completed site inventory surveys on about half

of the NPS property.

Some of the intensive surveys have been conducted

at the Alibates National Monument following

natural range fires. For instance, a study conducted by Paul

and Suzanna Katz under optimal surface

visibility identified numerous sites and quarry pits within

the monument boundaries. And other private and university

contractors have carried out surveys of the Bureau of Reclamation's

small property holdings adjacent to Sanford Dam.

Just upstream from Lake Meredith, jurisdiction

of the federal helium processing plant on the Cross

Bar Ranch switched from the Office of Surface Mining

to the Bureau of Land Management. Multiple archeological surveys

of the ranch have been conducted, including the development

of a predictive model of Antelope Creek site locations. These

surveys found that villages were often established near pour-off

plunge pools along secondary streams. These pool-side village

sites are often miles away from the Canadian River and must

have been linked to one another by trails.

Landergin Mesa

In 1981, Robert Mallouf, then

the State Archeologist of Texas, directed excavations at Landergin

Mesa for the Texas Historical Commission (THC). The work was

done to evaluate whether the site merited continued listing

as a National Historic Landmark. The THC

also sponsored additional excavations there in 1984 led by

Christopher Lintz. This mesa-top Antelope Creek village had

long attracted archeological attention because of its peculiar

defensive location—Landergin Mesa has no immediate water

source or nearby agricultural land.

Like many prominent Antelope Creek ruins, the

village atop the mesa had been badly disturbed by relic hunters.

Funding for the THC archeological work was pieced together

from federal, state, and private sources. Unfortunately, while

there was enough money for the fieldwork, laboratory stabilization

of records, photographs and specimens, and a few radiocarbon

dates, a full analysis and reporting has not yet been accomplished.

One of the enduring problems in archeology is that it is often

very difficult to find adequate funding for the final and,

ironically, most important part of any project—the hard

work of thoroughly analyzing the recovered materials and fully

reporting the results.

The THC investigations showed that, despite

extensive looting, substantial architecture and primary deposits

remained intact in some areas of the site. Landergin Mesa

was found to have had a long history of intermittent occupation

beginning in Late Archaic and Woodland times. Most of the

architecture (structural remains) dated to the Antelope Creek

phase, during which the half-acre mesa top saw remarkably

intense use. During the 1984 season, archeologists identified

ten structures from seven different occupations within a relatively

small excavation area covering 42 square meters (452 square

feet). One odd finding was that most of the houses seem to

have been built as isolated structures rather than the contiguous

rooms one might expect given the severely limited real estate

atop the mesa. The pattern of isolated-house construction

existed throughout the duration of the Antelope Creek phase.

Antelope Creek villagers apparently used Landergin Mesa as

a refuge in threatening times rather than as a permanent village.

A 2001 article by Lintz provides a useful summary of the excavated

features and details of the dating of the site.

Volunteers, Graduate Students, and Field Schools

Since the 1950s volunteers from archeological

groups and student “volunteers” from regional

universities have been involved in virtually all major excavations

of Plains village sites in the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles.

The involvement of local archeological societies

has been mentioned in the previous section as has the pivotal

role played by Jack Hughes. In recent decades the Panhandle

Archeological Society (PAS) has charted a different

course from that taken by its predecessor group, the Norpan

Archeological Society. The Norpan group, like many local societies,

carried out many excavations on its own, few of which were

ever completely analyzed and reported. In contrast, the PAS

has focused on helping others and on publishing reports that

have long languished in obscurity. PAS members routinely volunteer

on field research projects run by professional archeologists

and other established groups. Even more importantly, the PAS

has published several other important archeological studies

in addition to the Baker's WPA reports and Earl Green's report

on the Footprint site.

Field schools organized by statewide groups,

the Texas Archeological Society (TAS), the

Oklahoma Anthropological Society, and by

various state universities have also been part of the story.

While field schools are held primarily to provide training,

important research can also be accomplished.

In 1969, the TAS held its eighth annual field

school along Blue Creek, a tributary of the

Canadian, on National Park Service property near Lake Meredith.

Jack Hughes directed the week-long investigations

of four Antelope Creek sites by over 200 volunteers from across

the state. Three of the sites were hamlets or small villages

while the fourth was a small cemetery where children and infants

were buried. While TAS field schools are positive learning

experiences, 200 people can move a lot of dirt in a week and

create small mountains of artifacts and field records. Hughes

never found time to study the Blue Creek finds. Fortunately,

two of his former students, Jim Couzzourt

and Beverly Schmidt-Couzzourt, took on the

project in the 1980s. Their detailed report finally appeared

in 1996, an accomplishment that few non-archeologists could

appreciate — successfully completing such a project

years after the fieldwork is finished is an extraordinarily

difficult feat.

The TAS field school returned to the northern

Panhandle in 1987 and 1988 as part of new investigations of

Buried City. This time it was Jack Hughes’

son, David Hughes, who directed the work.

David, who now teaches at Wichita State University (WSU) in

Kansas, led new work at Buried City on behalf of the Harold

Courson family beginning in 1985 and 1986. The 1987 and 1988

TAS field schools were even larger than the one at Blue Creek.

Hughes also ran a WSU field school at Buried City in 1990.

The results of the Buried City work are presented elsewhere

on this website (see Buried

City Investigations).

In 2000, Scott Brosowske of

the University of Oklahoma (OU) began investigating new areas

in the Buried City vicinity using remote sensing techniques.

In the summer of 2003, an OU field school excavated several

pithouse structures Brosowske located.

Brosowske is one of the latest of many graduate

students who have studied Plains Villager sites in the Texas

Panhandle and nearby areas. Dozens of students working on

advanced degrees or participating in specialized research

studies at universities in Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and elsewhere

have contributed to what we know about Antelope Creek culture.

As is the case in many fields of study, most of the master’s

theses and dissertations written by archeology graduate students

are never formally published. This is unfortunate, because

many such studies are in-depth analyses that have significant

research contributions.

Among those graduate students who have stuck

with it and gone on to complete dissertations and published

studies are four that deserve special mention: Lathel Duffield,

Marjorie Duncan, Robert Campbell, and Christopher Lintz. Their

contributions are highlighted below.

Antelope Creek Paleoecology

In the mid 1960s, two scientists from Wisconsin,

archeologist David A. Baerreis and climatologist

Reid A. Bryson, published a series of articles

advancing a fascinating hypothesis that, in part, might explain

the origin of Antelope Creek culture. Using climatic data

and newly obtained radiocarbon dates from Antelope Creek sites,

they argued that deteriorating climatic conditions in the

central Plains about A.D. 1200 had caused Upper Republican

peoples to move south from Nebraska to the Oklahoma and Texas

panhandles shortly thereafter. While a central Plains origin

for Antelope Creek had been postulated in the 1930s by Wedel

and reinforced by Krieger and then Watson, Baerreis and Bryson

were the first to provide a clear mechanism and supporting

evidence. Their work was the first time that Antelope Creek

paleoecology, the biological study of ancient organisms (humans

included) and their environment, had been seriously considered.

Inspired by this work, Lathel F. Duffield,

a graduate student under Baerreis at the University of Wisconsin,

decided to undertake a detailed analysis of the faunal materials

(animal bones) recovered from 11 Antelope Creek sites. Duffield

obtained collections from the three sites he had excavated

in 1962 at Sanford Reservoir as well as a series of other

sites including Antelope Creek 22, Alibates 28, and Sanford

Ruin. His 1970 dissertation remains a critical source of information

on Antelope Creek diet, hunting patterns, and paleoecology.

For instance, he identified 38 species of mammals, 29 birds,

8 reptiles, and 2 fish among the bones he studied, clearly

showing that Antelope Creek peoples relied on far more than

buffalo. To be sure, bison was the most important species

at all the sites he studied, but Duffield’s data suggested

that there had been a drying trend during Antelope Creek times

that by A.D. 1300 resulted in fewer bison and more antelope.

Was this trend a factor in the demise of Antelope Creek culture?

Recently, Majorie Duncan

has completed her dissertation at the University of Oklahoma

on a detailed ecological study of the animal bones from the

Two Sisters homestead site in the Oklahoma Panhandle. The

Two Sisters site is thought to be a small

homestead occupied by a single Plains Village family over

a lengthy period of time. Duncan’s study relies on contrasting

the bone assemblages from two superimposed houses occupied

between A.D. 1300 and 1450 that presumably represent continued

site occupation by successive generations. In addition to

providing a comprehensive description of the site and its

material assemblage, she documents the use of 15 species of

identifiable mammals, 10 species of reptiles, one amphibian

species, 15 bird species, three fish species, and one mussel

species. Based on ranking the importance of various prey and

studies of long-term resource depletion, Duncan presents a

fascinating model of how the site may have been abandoned.

She reasons that the work of acquiring food became too difficult

following environmental deterioration (increasingly

drier conditions) and the immediate area could no longer be

effectively farmed, forcing the family to move elsewhere for

survival.

Apishapa and Antelope Creek Phases

In the late 1960s Robert Campbell

completed his doctoral research at the University of Colorado

on the Chaquaqua Plateau of southeastern Colorado. There he

found evidence of a Plains village group who were responsible

for what he called the Apishapa phase. Apishapa

peoples built circular houses with stone foundations and Campbell

proposed they were the ancestors and originators of Antelope

Creek culture. He expanded this idea in his 1976 book, The

Panhandle Aspect of the Chaquaqua Plateau. Campbell argued

that around A.D. 1200, the Apishapa Plains villagers were

forced to migrate as the result of a prolonged drought. They

moved, he argued, south and east into the Canadian River valley,

bringing with them their knowledge of stone masonry. In the

Texas Panhandle, they came in contact with late Woodland peoples

who were already living in rectangular subterranean houses.

According to Campbell, the mix of cultures resulted in the

typical Antelope Creek houses with stone foundations.

Two years after the publication of Campbell's

book, his migration theory drew a withering critique from

a graduate student, Christopher R. Lintz.

In a 1978 paper called "Architecture and Radiocarbon

Dating of the Antelope Creek Focus: A Test of Campbell's Model,"

Lintz argued that his own appraisal of Antelope Creek radiocarbon

dates suggested that the Apishapa and Antelope Creek cultures

were contemporaneous rather than successive. (Today the issue

is being debated again -- see Hank's

House 2.)

Lintz, in essence, had taken up the task of

defining Antelope Creek culture where Alex Krieger left off

over three decades earlier. Lintz had been introduced to the

subject in the early 1970s as a young graduate student at

the University of Oklahoma (OU). He took part in two OU field

schools held at Plains Village sites in the Oklahoma Panhandle,

the first in 1972 at the McGrath site and

the second the following year at the Two Sisters site. Lintz

wrote up the McGrath site for his 1975 master’s degree.

His interest in the region grew in the 1970s and early 1980s

while he worked on various contract projects and continued

his graduate studies.

For his dissertation research, Lintz critically

reexamined many aspects of Antelope Creek culture, focusing

on the small core area centered on a 50-mile stretch of the

Canadian Valley north and northeast of Amarillo. Lintz had

two key advantages over Krieger. First, of course, he was

able to incorporate the results of three more decades of research,

a period during which radiocarbon dating had become an important

tool. Secondly, Lintz devoted a great deal more time to the

project than Krieger had been able to and was able to track

down many primary field records and unpublished manuscripts

as well as published accounts. His 1984 dissertation (formally

published in 1986) is a critical source on Antelope Creek

culture. Lintz has also published numerous articles and reports

on Antelope Creek sites and related research topics.

Lintz reaffirmed the validity of the Antelope

Creek concept, redefining it as the Antelope Creek

phase within what he called the Upper Canark

variant of the Plains Village tradition. Practically

speaking, the Upper Canark variant is a slightly expanded

version of what Krieger called the Panhandle aspect.

As you might expect, given the provincial nature of most archeological

research, the new variant name has found favor among Oklahoma

and Colorado archeologists. Equally unsurprising is the fact

that Texas archeologists rarely use the term, if for no other

reason than because of its awkward construction (Upper Canark

= upper drainage systems of the Canadian and Arkansas rivers).

Among Lintz’ contributions

are these five accomplishments: (1) he classified cultural

variation in Plains Village life across the western half of

the southern Plains; (2) he revised the chronology of Antelope

Creek; (3) he recognized that the extreme diversity others

had perceived in Antelope Creek architectural form represented

mainly variation on a relatively simple set of basic functional

forms; (4) he marshaled considerable data in support of plausible

explanations of the origin, development, social organization,

and demise of Antelope Creek culture; and (5) he offered an

improved explanation of the interaction between Antelope Creek

villagers and Pueblo peoples to the southwest.

Lintz compiled the available dating clues and

carefully reviewed the chronology of Antelope Creek and defined

two subphases, an early one (A.D. 1200-1350) and a late one

(A.D 1350-1500), thus pushing back Krieger’s dates by

over a century. Rejecting the Upper Republican origins postulated

by Baerreis and Bryson, Lintz embraced Jack Hughes’

argument that Antelope Creek was a local development that

had its origins in the area’s earlier Woodland and Late

Archaic cultures. (While the "local origins" hypothesis

is still considered viable today, it has yet to be supported

by solid evidence.)

The architectural variation long noted among

Antelope Creek and related Plains Village sites had befuddled

archeologists for decades. Lintz argued that many of the differences

were superficial and were attributable more to the availability

of building materials (or engineering constraints due to room

sizes) and, especially, to the failure of archeologists to

fully expose and understand Antelope Creek architecture. He

defined two dominant forms of basic residential units—houses—as

well as several types of “subordinate structures”

representing storage rooms, work rooms, cooking areas, and

other specialized-function areas.

At most Antelope Creek sites, particularly the

multi-room “pueblos,” subordinate structures outnumber

the actual houses and have caused some researchers to overestimate

the number of people who had lived there. The archeological

attention lavished on the so-called "pueblos" in

the 1920s-1940s created the false impression that these were

archetypical Antelope Creek "village" sites. In

fact, these appear to be exceptional sites that only occur

in a small area and they are are far outnumbered by smaller

sites with isolated or paired houses and subordinate structures.

Antelope Creek sites that have architectural

remains, Lintz said, could be divided into three categories:

hamlets, homesteads, and subhomesteads. (Some site types,

like rock art sites, butchering locales, and flint quarries,

do not have structures.) Even the largest sites, such as Antelope

Creek 22, were really not villages, but hamlets where

no more than eight families had lived. Homesteads

were smaller sites with one main house and various

subordinate structures where a single family had lived. Subhomesteads

were sites with subordinate structures but no main houses

and probably were seasonal farmsteads or other limited use

areas.

In early Antelope Creek times, most people lived

in hamlets, including the famed “pueblos” with

continuous rooms as well as the more common clusters of individual

houses and subordinate structures. But by late Antelope Creek

times, most people lived in homesteads, a change Lintz thought

was caused by increasing drought and the difficulty of finding

enough resources to sustain larger social groups. Another

early to late change was a statistically dramatic increase

in the amount of traded pottery and other items from the Rio

Grande Pueblos to the southwest. Greater trade and interaction

after A.D. 1300 was, he argued, a response to less predictable

climatic conditions for farming. In a subsequent study Lintz

also documented the unusual existence of true mound construction

at Alibates Ruin 28, where a mound at least four feet tall

with some kind of elevated structure atop was constructed

during late Antelope Creek times.

Sophisticated explanations of complex social phenomena,

like Antelope Creek life, are complicated and must take into

consideration many factors. Lintz did not simply make assertions

and offer "just-so" stories; instead he presented

supporting data ranging from radiocarbon dates, plant and

animal identifications, artifact counts, room size calculations,

feature distributions and so on. His comparative regional

analysis of hard evidence is exactly the sort of scientific

study that had been sorely lacking in Antelope Creek studies

for so long. Lintz’ work was a much-needed synthesis

and new interpretation of Antelope Creek life upon which other

researchers will be building (and picking apart) for many

more decades.

Recent Developments

It is hard to make proper sense of any recent

history simply because we are too close to the events and

personalities. In archeology, for instance, years and even

decades can go by between excavation and final publication

and between the productive career peaks of leading authorities

and their successors.

The small archeological community of the northern Texas Panhandle

is still in transition following the death of Jack Hughes

in 2001. Hughes left an unequaled legacy of students and friends

whose involvement in archeology he inspired. He also left

behind many systematic artifact collections and supporting

documentation from many Antelope Creek sites. As in many areas

of the state, much unglamorous work remains to be done to

tap the potential of these important collections.

Happily, there are positive developments underway. Government-sponsored

and government-mandated archeological research will continue

to provide new opportunities. Landowners such as Harold

Courson (Buried City), John Erickson

(northern Roberts County), and Pete Thurmond (Dempsey

Divide in western Oklahoma) are devoting their own time and

resources to learning more about the history of their land.

Veteran professional and avocational archeologists, many of

them Jack’s formers students, continue to be interested

in the archeology of the region, even those who have moved

away. For instance, Panhandle natives Doug Boyd

and Brett Cruise are professional archeologists

who have been returning to the region to help Erickson investigate

a little known area of the Canadian River Valley. Members

of the Panhandle Archeological Society, the TAS and the THC’s

stewardship network, such as Rolla Shaller,

Alvin Lynn, and Doug Wilkens

(among others), are involved in almost every field project

in the region. Graduate students from various universities

including the University of Oklahoma, Wichita State University,

the University of Texas at San Antonio, and Texas A&M,

are analyzing old Antelope Creek collections and undertaking

new research. Scott Brosowske’s work at Buried City

and other sites exemplifies the contributions that graduate

students are making. Finally, we note that Oklahoma professional

archeologists, such as Richard Drass and

Robert Brooks at OU, are studying Plains

Village and Woodland cultures in western and southern Oklahoma

that offer close comparisons with the villagers of the Texas

Panhandle.

|

| |

| Antelope Creek culture

was a lot less uniform and a lot more interesting than

earlier archeologists had believed. As is invariably the

case with ancient cultures, the more we learn, the more

we realize we still don't know. |

Borger Cordmarked pottery sherds

from the Congdon's Butte site in northeastern New Mexico,

one of the westernmost Antelope Creek sites. This earthenware

pottery provided basic household needs—storage

and cooking. The ruler at the bottom of the picture

is marked in centimeters. Photo by Chris Lintz. |

The “Big House” at the

Black Dog Village site is a large, classic Antelope

Creek house that is much larger than the other known

houses there. Archeologists from the Texas Highway Department

also exposed four, smaller rectangular structures that

are probably more typical houses and it is suspected

that numerous other rectangular and circular house patterns

may have been present elsewhere at the site, beyond

the highway right-of-way. |

Plan map of the “Big House”

uncovered at the Black Dog Village site. This large

structure (18 by 26 feet) has many of the features identified

in classic Antelope Creek houses including a central

depression or “channel” flanked by slightly

raised benches and roof-support posts, central hearths,

partial slab wall construction, and an apparent “altar”

opposite the entranceway. Click to see full

image. |

In the 1970s, Meeks Etchieson was

one of the most active government archeologists to be

stationed in the Texas Panhandle. Etchieson, who worked

for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, carried out surveys

and salvage excavations on federal land around Lake

Meredith. Photo by Chris Lintz. |

Archeologists have recorded numerous

partially exposed Antelope Creek houses on government

property surrounding Lake Meredith. This house, like

many, has been dug into by a treasure hunter. Such acts

are against the law on federal property. Photo by Chris

Lintz. |

| |

Archeologists expose the remains

of Antelope Creek houses that once stood atop Landergin

Mesa in 1984. Photo courtesy Chris Lintz. |

Archeologists get help hauling sterile

sand to the top of Landergin Mesa to stabilize and protect

the 1984 excavation block. Photo courtesy Chris Lintz.

|

The 1996 Bulletin of the Texas

Archeological Society features a final report by

Jim Couzzourt and Beverly Schmidt-Couzzourt on the 1969

TAS field school at Blue Creek. Few non-archeologists

can appreciate how difficult it is to successfully complete

such a project 15 years after the fact. |

TAS members pause while screening

excavated sediment during the 1969 TAS field school

at Blue Creek. In the background Lake Meredith is visible.

Photo by Wallace Williams |

Pronghorn antelope appear to be better

adapted to drier conditions than bison. Lathel Duffield

used this observation to interpret the increased numbers

of antelope bones relative to bison bones in Antelope

Creek sites as a sign of worsening drought. Photo courtesy

Texas Parks and Wildlife. |

One of three circular rooms flanking

Structure A, the latest of two rectangular houses at

the Two Sisters site. The scattered rocks on the room

floor may have been used to weigh down a grass-thatched

roof. Beneath the floor were several large storage pits.

Photo by Chris Lintz. |

For his dissertation at the University

of Colorado, Robert Campbell studied Plains Village

sites in the Chaquaqua Plateau of southeastern Colorado.

These, he argued, represented an Apishapa phase that

he thought preceded the Antelope Creek phase. Campbell

later became a professor of anthropology at Texas Tech

University. |

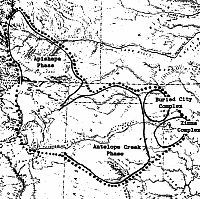

This 1989 map by Chris Lintz shows

the approximate territories of the Antelope Creek and

Apishapa phases as well as of the Buried City and Zimms

complexes. All are related Plains Village cultures that

coexisited around A.D. 1300. The dotted line is the

boundary of the Upper Canark variant, the name Lintz

gave to what earlier researchers called the "Panhandle

aspect." |

The picturesque valley of Antelope

Creek, namesake of the Antelope Creek focus, phase,

and culture. This photo was taken near Antelope Creek

Ruin 22, one of the culture's most impressive sites.

Photo by Chris Lintz |

| The Naming

Game What the reader may suspect

is true: we archeologists sometimes spend an inordinate

amount of time coining new names, arguing over definitions,

and otherwise splitting taxonomic hairs. We have our

reasons, but explaining these might put you to sleep.

Alas, it does make it hard for the non-specialist to

follow, especially when trying to compare articles or

reports written years apart. |

Apishapa phase artifact assemblage.

Click on image to see details. From

Lintz 1986, Figure 4. |

Antelope Creek villagers living at

Alibates Ruin 28 and other nearby villages (hamlets)

quarried the local material and made thousands and thousands

of tools for export/trade to other villagers and other

groups who lived elsewhere. Shown here is a large quarry

"blank" (unfinished biface) and a hammerstone.

PPHM collections, photo by Steve Black. |

Jack Hughes (left) receives the Floyd

Studer Award for outstanding contributions to Panhandle

archeology from the Panhandle Archeological Society

in 1999. On the right is Alvin Lynn, then the president

of the PAS. Photo by Doug Boyd. |

Charred corn cobs have been found

at many excavated Antelope Creek sites. Recent studies

have cast doubt on the extent to which villagers depended

on corn. Corn may have provided a relatively small part

of the diet. PPHM collections, photo by Steve Black. |

|