Excavation plan at the Hueco Tanks village site, showing locations of houses, burials, and other features (adapted from Kegley 1982: Fig. 2).  |

Excavation crew poses at the village site. From left, Carol Wagner, Don Broussard, Roy Brooks, Logan McNatt, and George Kegley. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

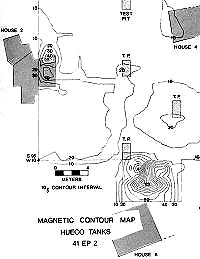

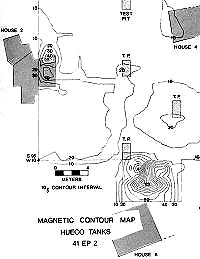

Magnetic contour map of Hueco Tanks village. The magnetometer survey, conducted by J. Barto Arnold III, detected numerous anomalies in the village area, including three additional pithouses. Graphic from Kegley 1982 (Fig. I-2).  |

Cover of the 1980 report of investigations at the Dona Ana village site by George Kegley.  |

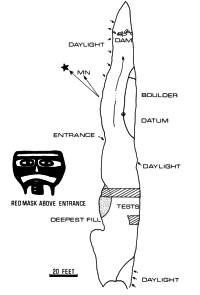

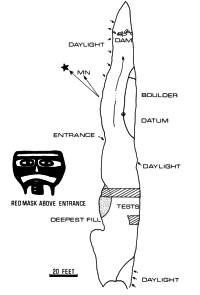

Drawing of cavern floor with small, catchment dam (shown at top) and “thirsty man” mask pictograph nearby. Tests dug into the cavern deposits produced pottery sherds and a few dart points. Drawing by John Davis as adapted in Kegley 1980 (Apx. VII).  |

TPWD survey director Margaret Howard digs a shovel test near a park kiosk during the 1999-2001 survey project. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Logan McNatt and another TPWD crew member conduct tests near the historic stone ruins near park headquarters. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

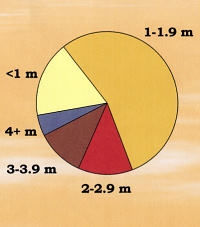

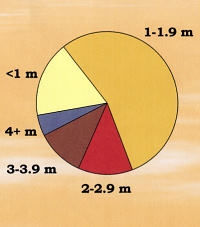

Variance in maximum size of burned rock features recorded during survey. Although analysis of data collected during survey is ongoing, small features predominated in this sample of 64 and there appears to be a correlation between feature size and type of rock used. Graphic courtesy of Margaret Howard.  |

The 125 visible fire-cracked rock features were concentrated in certain areas of Hueco Tanks, with 76 (61 percent) in one of the archeological localities. |

|

Village Excavations

The only large-scale archeological excavations in the park uncovered the remains of a small Jornada-Mogollon village. In 1972, members of the EPAS and the University of Texas at El Paso Anthropology Club recommended testing of an extensive midden on the east side of the rock hills. Directed by TPWD archeologists George Kegley and Ron Ralph, subsequent excavations consisted of approximately 40 units. Two backhoe trenches were also dug. Most of the units were placed in blocks around three semi-subterranean pithouses.

House 1 contained two postholes and a collared fire hearth. A piece of wood from one of the postholes yielded an uncorrected radiocarbon date of 800 BP ± 50 years. Calibrated, the date is 733=/- 39 years, with a range of A.D.1178-1256, a span falling within the latter part of the late Doña Ana and early El Paso phase. Associated with the fire hearth were an ash lens, an El Paso Polychrome olla sherd, three stones, and bones from badger (Taxidea taxus) and pronghorn antelope (Antilocapra americana). House 2 included a collared fire hearth, an adobe block that may have served as a step, a possible collared posthole, an intrusive pit, and a burial. House 3 included a collared fire hearth, two postholes, and two intrusive pits. The pits appeared to be refuse deposits dating after abandonment of the houses, and contained dark grey ashy midden soil and bones of bison, deer, pronghorn antelope, grey fox, badger, jack rabbit, cottontail rabbit, pack rat, box turtle, and rattlesnake.

At the beginning of the 1973 season, a magnetometer survey was conducted in the midden area investigated the previous year. The purpose was to locate anomalies in the earth’s magnetic field that might be caused by subsurface cultural features such as pottery concentrations, burned pithouses, or fire hearths. Two survey techniques were used—a controlled systematic mode using 1 m intervals, and a less precise search mode that covered a broader area. Testing of the five anomalies located during the systematic mode found three pithouses, a concentration of ceramics and lithics, and an iron bar that was part of the 1972 survey grid. Six anomalies were located by the search mode and three were tested, but no cultural features were found.

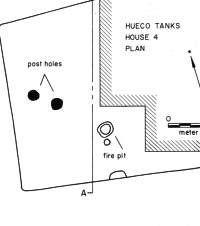

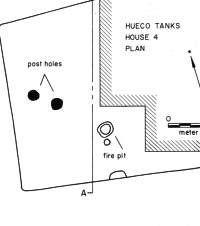

The 1973 excavations covered approximately 75 square m (807 square ft), consisting of 75 units Most of the units were concentrated in blocks around the three semi-subterranean pithouses located by the magnetometer survey. House 4 was not completely excavated; features included a collared fire hearth with associated circular pit, and two postholes. House 5 was in poor condition and encompassed two floors. Upper floor features were two postholes, a shallow basin with a metate and mano in situ, and an intrusive pit. Partial excavation of the lower floor exposed a fire pit and a posthole. House 6 contained two large postholes and 14 smaller ones, a fire pit, and a small shallow pit.

To archeologist Ron Ralph, who served as crew chief at Hueco Tanks village, the houses were unlike any he had ever seen at the time, “all single structures, rectangular, dug in the ground, and all oriented north-south.” It was frustrating, he says, that they were not able to determine whether the houses were made of puddled (poured) adobe or wattle and daub (vertical poles and branches covered with mud). The corner areas were the best preserved, he recalls, with the best wall definition. “But once you found the corners, you knew you were at the end of the house. The plaster would lip up and then go away.”

Artifacts recovered from the excavations were dominated by ceramic sherds; nearly 34,000 were counted. Chipped stone artifacts includednearly 80 projectile points, bifaces and assorted other other tools, and more than 24,000 pieces of debitage (chipping debris).

Nearly 50 ground stone tool were recovered including 32 manos, 10 slab metates, and 5 basin metates; these were made from limestone, sandstone, and the local syenite porphyry. Two Olivella beads, one discoidal bead, a small pendant, and a bone awl made from a splintered deer bone also were found.

Further details on findings and more recent research is provided in the Village Life section.

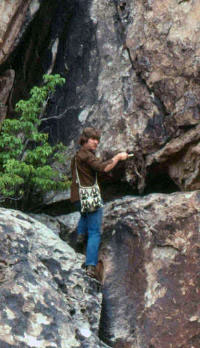

Investigations of Water Control Features

In conjunction with the 1972 excavations, a prehistoric water control system was investigated by the EPAS. Located in a large crevice on West Mountain, it consists of a man-made reservoir and two natural huecos. A rock dam had been constructed at a narrow point in the crevice to create the reservoir; the impoundment area is 30 m long and averages 3 m wide, and was estimated to have a maximum capacity exceeding 10,000 gallons. Two hand-excavated trenches in the reservoir fill yielded El Paso Polychrome and Chupadero Black-on-White sherds, and a variety of lithic items including two point fragments and three scrapers. The only pictograph in the reservoir area is a yellow geometric design that resembles designs on pottery.

Farther down the crevice are two large natural huecos that measure 5 m deep and have an estimated capacity of 780 gallons. Removal of the fill in one of the huecos yielded a dart point and dart point fragment, a handful of chipped stone flakes, and numerous sherds. The bedrock surrounding the huecos is highly polished, indicating long-term use probably by both human and animal visitors. The only pictograph associated with the huecos is a red mask that appears to have its tongue extended, possibly representing thirst.

Surveys and Ongoing Analyses

The 1970s saw a succession of projects initiated to record cultural resources prior to construction of trails, picnic areas, and other developments at Hueco Tanks State Historic Site. The numerous midden deposits and rock art localities throughout the park presented difficulties for any development, so a comprehensive set of guidelines was established to protect the sites. TPWD archeologist Ron Ralph recommended an intense 100 percent survey of the entire park and plotting all cultural resources on a topographic map all cultural resources including middens, rock art, pack rat middens, water control devices and surface artifacts.

Concerns about preservation of the site’s cultural and natural resources prompted development of a Resource Management Plan in 1998 and establishment of a Public Use Plan. To support increased stewardship of cultural resources, two inventory studies were initiated in 1999. As noted above known rock art sites were relocated and documented by Rupestrian CyberServices, Inc. Their findings are discussed further in the Rock Art section of this exhibit. Cultural deposits were inventoried by the TPWD Archeology Survey Team through intensive pedestrian survey of the ca. 500 acres of level terrain around the rock hills. The site was divided into 29 localities encompassing areas of moderate to high surface artifact density. Archeological localities were defined to encompass cultural deposits of a consistent density and type, but in areas where cultural deposits were continuous they were arbitrarily bounded at natural and/or manmade landmarks, to provide convenient units for analysis and management.

Survey took place over 141 person-days, for an average of 3.5 acres per person-day. The density of the cultural materials and features exposed on the surface necessitated this slow pace. With crew spaced at 20 to 30 meter intervals, the features and time-diagnostic, nonlocal, and distinctive artifacts were flagged for recording or collection. Data collected include time-diagnostic artifacts

(e.g., dart and arrow points, rim sherds, and decorated prehistoric and historic ceramics), materials suitable for radiocarbon assay, and information on the location and stratigraphy of cultural deposits.

The locations of collected artifacts, artifact concentrations, burned rock features, bedrock grinding features, middens and ashy soils, rock art panels, water control features, rockshelters, shovel tests, and significant natural features like water chutes were plotted on detailed maps derived from aerial photographs, at a scale of 1 inch = 100 ft/30 m. Large-scale aerial-based maps (1 inch = 200 ft/61 m) were used for localities where cultural materials and/or features were dense. Cultural features were briefly described, mapped, and photographed.

One to two shovel tests were dug in each archeological locality to sample the depth, stratigraphy, and integrity of the cultural deposits, and to facilitate collection of sediment samples for flotation and pollen analysis. Rockshelters were not tested due to their great number and the possibility that they could contain human burials.

Additional survey, this time in the lower elevations of the hills, was instituted when it became apparent that these areas were replete with rock art, cultural features, and historic graffiti. Natural features like water chute scars and rockshelters also were recorded, the latter defined as areas enclosing at least 10 square meters. Reconnaissance of the hills reached a height of 10 to 20 ft above ground surface as possible. A 100 percent survey of the hills was difficult to achieve because the rock surface is complex; many pictographs and other features are only visible under specific conditions (e.g., by early morning light in spring, on overhanging surfaces).

Preliminary analyses indicate that the 29 archeological localities defined in this area were occupied primarily during the Formative period, with Archaic occupations at half of them and one Paleoindian occupation. Most of the typed ceramics represent the late Formative period, while most of the projectile points are affiliated with the Late Archaic period. The relative abundance and types of nonlocal ceramics suggest that interaction during the Formative period was primarily with areas to the north. Ongoing analyses include ceramic and lithic source identification, radiocarbon assays, and flotation of midden sediments to recover pollen and/or plant remains.

It is clear that the state historic site contains significant cultural resources, with considerable potential to address questions in major research domains. Further analyses will help more clearly define the site’s context in regional

prehistory and history and yield substantial information that can be used to interpret the site for the public. These include regional questions of chronology, settlement and subsistence, interaction, and historic occupation.

Further, the location and distribution of cultural resources identified through these varied investigations is being used to guide trail planning and to delineate visitor access zones, with careful attention paid to how to preserve and protect the park's cultural heritage. |

Two trenches dug through the midden area helped investigators understand the nature of the deposits. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Excavation of one of the basin metates. Image courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Plan of House 4 and section, showing adobe wall remnant, post holes and firepit. Drawing from Kegley 1982 (Figure 8).  |

A collared post hole in House 5 is brushed clean for closer viewing. Image courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

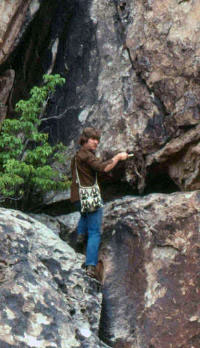

TPWD staff member Dave Parker points out the high water mark on a wall behind a small prehistoric “dam” in a deep crevice. Tank capacity is estimated at 10,000 gallons, and water still stands periodically in this feature. Photo by Ron Ralph.  |

TPWD archeologist Ron Ralph checks a rock art location at the park.  |

Documentation of some 125 burned rock features included extensive description, measurements, photographs, and shovel tests. The form shown, two of five pages for one feature recorded by TPWD archeologists Margaret Howard and Tim Roberts, indicates the level of detail required. Click to see full image.  |

A crew member records a burned rock feature amid the desertscrub. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Examples of arrowpoints recovered during investigations. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Rockshelters were investigated during the months-long survey, and features such as the bedrock mortars, shown in forefront, recorded. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

|