Floor of House 6, the largest structure at the village. Because of its size and relationship to an adjacent room, House 6 was thought to be either a communal structure or nascent form of puebloan two-room block. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Collared hearth adjacent to possibly collapsed wall in House 1. The raised collar, or coping, formed a protective barrier around the small hearth and served to contain the hot coals and sparks. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Pottery sherds uncovered during excavations. Image courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

The dearth of architectural timber in the Hueco Tanks houses may have resulted from them having being dismantled and robbed of their posts after the village was abandoned. |

Excavations underway at Hueco Tanks village. Image courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

| In addition to corn and beans, village meals at times included rabbits, gray fox, raccoon, cougar, and a variety of rodents: rats, mice, gophers, and prairie dogs. Larger mammals obtained by hunters included deer, antelope, and black bear. The villagers also ate several varieties of turtle, rattlesnakes, and birds, including dove and road runner. |

Remains of antelope were among the large quantities of animal bones found in trash pits. This evidence, along with more than 70 projectile points found during excavations, tells us that large game animals were important in village diet. Photo courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

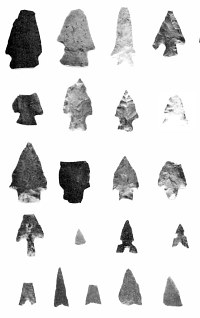

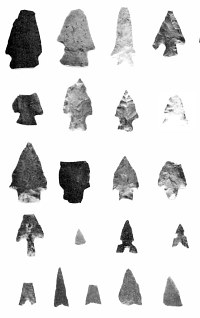

Examples of the more than 70 projectile points, including both dart points and arrow points, recovered at the site. Such large numbers of points are unusual in Formative period habitation sites of comparable size. Photo from Kegley 1982.  |

Pictograph of “goggle-eyed” figure with geometric-design on body. Many rock art depictions at the site, while broadly attributable to the Jornada Mogollon culture, cannot be assigned to specific phases. Photo by Rupestrian Cyberservices, courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

|

The Hueco Tanks structures were semi-subterranean, that is, built within shallow pits with walls rising above ground. Ranging in size from about 7.5 x 7.5 feet to a little over 12 x 13 feet, most of the structures were not much larger than walk-in closets or small bedrooms in modern houses today. House 6, however, was larger, measuring roughly 15 x 18 feet and with paired central roof support posts nearly 20 inches (50 cm) in diameter. There were other differences in this structure: outside the east wall area of House 6, archeologists found a prepared floor surface covered with charred material and several lumps of adobe brick. The difference in overall size and the presence of the additional floor area led Kegley to suggest House 6 might have been a two-room structure, perhaps a nascent form of the contiguous-room pueblos of later times. Alternatively, it may have been a communal room where gatherings and ceremonies were held. In later pueblo villages, subterranean kivas served this function. ( Download pdf file to read Kegley’s description of each structure for more detail. ) Download pdf file to read Kegley’s description of each structure for more detail. )

For the villagers, the construction process would have entailed first digging the pit, usually not deeper than a few feet (about a meter). Near the center of the room, two large roof support posts, typically aligned east-west, were placed equidistant from the walls to provide support for the superstructure. The floor was coated with a layer of adobe plaster that, on several houses, extended up the walls of the pit. A small firepit was dug into the floor on the south side, and a plastered collar, or coping, was molded up around the edge to surround the pit. The firepits may have been used to hold hot coals for warmth, rather than actual fires which would have been hazardous in the small structures.

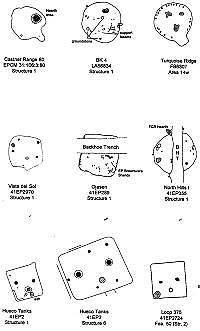

Entry into the houses may have been achieved by ladders through the roof, although the evidence was ambiguous. In one of the houses, an adobe block “step” was built at the south wall of the pit. The step may have been part of an entryway or related to placement of a ladder. In other houses, no clear evidence of an entryway could be discerned. As is evident in the house plan maps (see rollover map), several houses contained smaller postholes which might have been related to an earlier structure or a sheltered outdoor extension to the house.

How the exterior walls and roofs of the houses were constructed, however, and of what material, remains a matter of conjecture. A few “molded lumps” of adobe found on, and above, several house floors led Kegley to suggest that the walls exterior to the pits might have been built of adobe, perhaps in a construction mode somewhat similar to the houses at the Polvo site in the La Junta District. He attributed the dearth of structural evidence at the Hueco Tanks site to sheet erosion which might have washed away any above-ground walls. Others believe it more likely that the walls were not solid but more open to the air, with layers of brush covering vertical wooden posts. Examples of this type of construction were seen at the Ojasen and Gobernadora sites where Doña Ana pithouses were crafted of vertical agave stalks covered over with grass. Roofs also may have been constructed of agave stalks and grass and covered over with adobe. At these sites, there were more distinct alignments of postholes as well as perishable remains to aid in interpretation. Pithouses apparently pre-dating a large, multi-room pueblo were uncovered at the Firecracker Pueblo site near El Paso. These rectangular houses contained many of the same structural elements as those at Hueco Tanks and provide an interesting view of a later manifestation of this form.

Archeologist Ron Ralph, who served as crew chief at Hueco Tanks excavations, believes that the lack of architectural timber in the Hueco Tanks houses—excepting the paired interior postholes and additional small alignment of holes in House 6—may have resulted from the houses being dismantled and robbed of their posts after the village was abandoned. Reuse and recycling he notes, may have been a common pattern in prehistoric times, given the scarcity of wood in the Chihuahuan Desert. Ralph also recalled that the floors appeared to have been patched in some places. Digging through them was almost like troweling “layers of laminate, like many layers of mud had been poured over time.”

Several of the houses appeared to have been re-used for other purposes after abandonment, an indication that not all the houses were in use contemporaneously. In two houses, villagers dug pits into the floor and deposited trash, including large quantities of animal bone. In another house (House 2), the body of an adult was buried in a corner, in fill just above the floor. The individual was positioned on its back, with arms folded at the waist, legs drawn up, and head oriented to the west. Three other burials were found during the 1972 excavations but their association with the village was not certain. Two of the burials contained El Paso Polychrome sherds.

Traces found inside the structures and village commons help us envision daily life in the small community. Within the houses, villagers had a hearth for warmth and cooking and, in some, areas for food processing and other tasks, perhaps on days when weather was too inclement for work outdoors. In House 1, the likely remains of a family meal—bones of badger and antelope—were found along with fragments of a decorated ceramic olla (El Paso Polychrome) in an ashy lens near the firepit. House 5 contained a large groundstone milling bin lying on the floor.

Based on identification of excavated animal bone, village meals at times included rabbit, gray fox, raccoon, and a variety of rodents— rats, mice, gophers, and prairie dogs. Larger mammals obtained by hunters included deer, antelope, cougar, and black bear. The villagers also ate several varieties of turtle, rattlesnakes, and birds, including dove and road runner. Bison also were hunted at Hueco Tanks; this animal, however, was extirpated in the area during historic times.

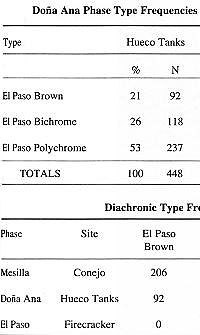

The large numbers of projectile points—more than 70, including both arrow and dart points— are another strong indicator of the importance of medium- to large-sized mammals in the village diet. (The many small rodents and rabbits reflected in faunal remains at the site likely were trapped or netted by hunters.) Such large numbers of projectile points are a rarity in Formative period habitation sites. In his study of neighboring sites in the western Trans-Pecos, archeologist Myles Miller noted a total of only 27 specimens reported from at least 35 pithouses and other features at the Turquoise Ridge, Gobernadora, Ojasen, and Meyer Ridge sites.

Reconstructing the plant portion of villager diet has been more difficult, due to poor preservation of floral remains. Miller processed five large flotation samples collected during site excavations. Identified remains included both wild and domesticated plants: corn (Zea mays), prickly pear seed (Opuntia sp.), mesquite bean (Prosopis sp.), amaranth or chenopodium seed (Cheno-am), domesticated bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), and Banana yucca seed or fruit (Yucca baccata).

Villagers had access to a variety of desert plants, particularly leaf succulents such as agave, growing in nearby areas. Several large clusters of hearths and earth ovens, associated with ceramic sherds attributable to the Doña Ana phase, were documented by archeologist Margaret Howard during survey of Hueco Tanks. Although these features cannot be directly related to the village, a connection seems possible. Villagers might have roasted the plants while staying at field camps, then completed processing back in the village using grinding tools—manos and metates. Village crops, such as corn, also were ground into meal using groundstone tools. Both slab and basin metates were recovered at the village. All of the manos were hand-sized, unlike the larger, two-handed manos typical of later El Paso phase sites. Studies of groundstone “appliances” from other sites by UTSA archeologists Robert Hard and Raymond Mauldin indicate that metates as well as manos increased in size as corn was introduced into the diet and that the shapes of these grinding implements were altered as well to accommodate corn.

Across the region, the dual subsistence pattern of growing crops and harvesting wild plants continued throughout the Formative period, but with varying intensity. Archeologist Myles Miller, who has studied burned rock features in sites throughout the region, holds that rock-lined pit cooking peaked between A.D. 1150 and 1250 during the Doña Ana phase and that processing of wild plants intensified in tandem with an increase in agricultural production during the later, El Paso, phase.

|

Fallen adobe found in several of the houses may be remnants of wall or roof covering. The rubble shown is from House 6. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

What the Houses Can Tell Us:

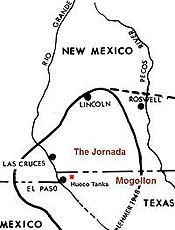

The Hueco Tanks Village houses, or "pitrooms," exemplify many of the more formal construction elements common in Doña Ana structures which distinguish them from less durable and typically circular pithouses of the earlier Mesilla phase.

- Angular shape

- Paired support posts aligned on a central axis

- Prepared floors of plaster or adobe

- Collared firepits in consistent locations

- Refuse pits

Researchers see a correlation between these more durable architectural forms and a more sedentary lifestyle and, by implication, an increased dependence on horticulture. Construction of a Doña Ana house was more labor intensive and involved a greater commitment to the locale. On a larger, regional scale, researchers have correlated the transition to angular house forms in the Hueco Bolson with settlement in the alluvial fan piedmonts, away from the central basin. |

A collared post hole in House 5 is brushed clean for closer viewing. Image courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

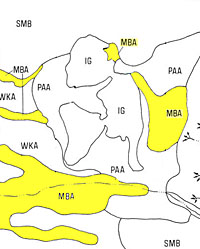

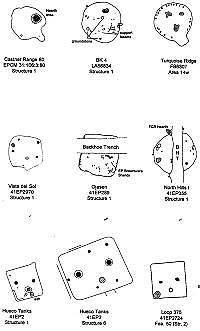

Comparisons of house forms during the Formative period in the western Trans-Pecos. The upper two rows show examples of structures of the Mesilla Phase. The lower row includes examples of isolated rooms from the transitional Doña Ana phase and El Paso phase. At bottom left are House 1 and House 6 from Hueco Tanks. Graphic by Myles Miller from Perttula 2004 (Fig 7.21).  |

A village woman grinds corn using a two-handed mano and metate typical of later El Paso phase sites. Inset from painting by George Nelson, based on Firecracker Pueblo, courtesy of the Institute for Texan Cultures.  |

Excavation of one of the heavy basin metates. Image courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

|