Weaving the Story: The People of Hueco Tanks

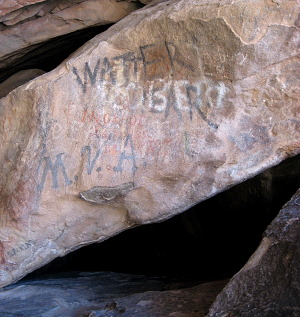

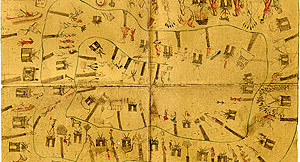

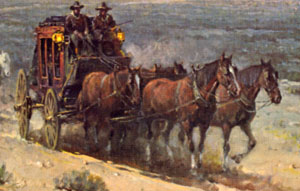

For some 10,000 years, Hueco Tanks has attracted people who visited and camped around the rock hills, and left traces that archeologists can interpret. The water sources, plants, and animals in and near the Tanks made the area an oasis in the desert. Evidence of many different groups that frequented the area has survived in the form of images drawn on the rocks, broken items left behind, and stained soils in areas that were intensely occupied. Around 1,100 years ago the sandy land surface in this area stopped building up, so most of the discarded items, hearths, and house patterns left by people since that time remain on or near the modern ground surface. The highly visible and shallow archeological record of Hueco Tanks is easily damaged by activities that erode the ground surface, and many have occurred there. The Tanks were a stopping point on a western trail for several decades in the mid nineteenth century, and the center of an active cattle ranch for over 60 years. The hills have been a recreation spot for at least 100 years. In 1939, artist Forrest Kirkland noted that "Flint flakes and pot sherds are plentiful throughout the entire area but artifacts [complete objects] of all kinds are extremely scarce now." A number of artifacts were carried away by visitors before property was conveyed to the state of Texas in 1969. The archeological and historic record of Hueco Tanks State Park and Historic Site is now protected by the Antiquities Code of Texas, and through the Public Use Plan for the park. Archeologists and historians have traced the human history of Hueco Tanks by looking at information visible on the ground surface and the rocks. A comprehensive study has been completed by Texas Parks and Wildlife archeologists Margaret Howard, Logan McNatt, Tim Roberts, Amy Ringstaff, and historian Terri Myers. They first sought information through artifact styles, features, radiocarbon dating, and archival research. Additional data on the rich historic fabric of Hueco Tanks came from rock imagery styles, artifact densities in shovel tests, and historic inscriptions. Together, these diverse information sources provide a detailed record of the timing and location of human activities at this special place. Although Hueco Tanks was not occupied continuously for 10 millennia, it is the only place in the region where every prehistoric and historic time period is represented. Water was the main resource that spurred repeated use of areas around the rock hills during this long time span. Beginning in prehistoric times it was retained behind simple dams, allowing greater numbers of people to gather. The rock hills strongly influenced settlement in other ways: they provided shelter, served as a canvas for rock imagery, provided a base for food-processing facilities, and yielded fragments for use as heating elements in hearths and plant roasting pits. The earliest people at Hueco Tanks were Paleoindian hunters wielding spears with Folsom points, who used a narrow pass between the rock hills to hunt herd animals, probably bison. Early, Middle, and Late Archaic groups hunted a diverse array of smaller animals, and processed wild plants in rock mortars while occupying nearby shelters. The most intensive occupations took place during the Doña Ana phase, between A.D. 1000 and 1300, when groups occupied many areas around the rock hills. In the northeast part of the Tanks, a cluster of rectangular houses was built near areas of moist soils that were used as fields. In another area, leaf succulents were harvested from patches where they thrived, and roasted in bulk in rock-lined pits. Almost all of the items used by prehistoric groups during this time were obtained in or near the Hueco Bolson, but pottery reached them through an interregional trade network that involved groups to the north and northwest, and to a limited extent, Mexico. Hueco Tanks also was a focal point in the sacred landscape of the eastern Hueco Bolson for a thousand years or longer, beginning in Late Archaic times. The abundant rock imagery primarily appears to represent ritual petitions for rain; sacred precincts were established high on the hills, and the Tanks were the final resting place for many. Native groups established a trail that ran through the Tanks toward water and salt sources on the east, and their descendants guided military scouts and travelers along it, beginning in 1692. During the centuries that followed, gold-seekers, cattle drovers, military and railroad surveyors, and other adventurers on the trail marked their names on the rocks. A stage station was briefly established at the Tanks in the late 1850s. The first permanent historic occupation was the Escontrias ranch, established in 1898 and operating until 1956. Military training was conducted at the Tanks in the 1940s and 1950s. Recreational activities that began before the turn of the century culminated in establishment of the state park in 1970. This many-faceted story is reviewed below. Earliest PeopleThe earliest human-made objects found at Hueco Tanks are fluted lanceolate points of the Folsom culture. Between 9,000 and 8,200 B.C., these mobile groups hunted large herd animals across the grass-covered basins between the mountain ranges. In this region, Folsom hunters spent the winter in the broad basins near the Rio Grande valley, and then headed north to hunt on the southern Great Plains during the summer and early fall. Although the diet of Folsom people included a number of plants and animals, their most notable prey was the huge straight-horned Ice Age bison, Bison antiquus, now extinct. Folsom camps typically were positioned at locations offering an overview of the surrounding area and ready access to water. At Hueco Tanks, Folsom lance points were found on the rocks above a pass between two rock hills; bison could have driven between the hills and hunted easily from that vantage point. Other Folsom camps in the region have been found in similar settings, including sites LA93330, LA93331, and LA93336, located on a ridge above an intermittent drainage in the Tularosa Basin of New Mexico. Folsom points were clustered around Three Buttes-bedrock outcrops overlooking several large playas. In the San Andres Mountains, a campsite containing Clovis and Folsom points and end scrapers was positioned at the mouth of Rhodes Canyon. Early Paleoindian tools and Folsom points were found in sites 41HZ504 and 41HZ505, on the upper Hueco Mountain alluvial fan near Padre Canyon. Although many Folsom camps have been recorded in the region, sites dating to earlier (Clovis) and slightly later (Plainview and Scottsbluff) Paleoindian periods are not common. Some sites of this age probably are deeply buried. The big game hunting period ended because climate changes apparently caused a decline in large herd animals and Bison antiquus became extinct, causing groups to adopt a broader diet based on a variety of medium-sized and small animals and plants. The earliest human-made objects that have been found at Hueco Tanks are fluted lance points of the Folsom culture. By 10,200 years ago, these groups roamed across the region and hunted a large type of bison (now extinct), along with smaller animals. The weather was milder than it is today, with cooler summers, warmer winters, and greater rainfall. Folsom hunters spent winters in the broad basins near the Rio Grande valley, and then headed north to hunt on the southern Great Plains during the summer and early fall. Folsom camps were occupied briefly, and typically were located in places offering an overview of the surrounding area and ready access to water. Hueco Tanks offered all of these advantages to Folsom hunters, who camped in the pass between two of the rock hills. Bison could have been driven through that canyon and hunted easily from the hills above. A few late Paleoindian lance points reveal that hunters continued to camp and hunt in the pass after the Folsom people left. As the climate warmed between 9,000 and 8,000 years ago the large bison became extinct, and people adopted a broader diet based on medium-sized and small animals, supplemented by plants. Hunters began to use throwing sticks we call atlatls to launch dart points fastened onto spears. From 8,000 to 6,000/5,000 years ago during the Early Archaic period, Hueco Tanks was visited occasionally as hunters moved seasonally from camp to camp. Visits to the Tanks increased between 6,000/5,000 and 3,200 years ago during the Middle Archaic period, when activities were focused on the central area between the rock hills. In Late Archaic times between 3,200 and 1,800 years ago, populations were growing in the region, and many groups camped for short periods around the rock hills of Hueco Tanks. In the southwest part of what is now the state park, a longer-term camp composed of small, temporary huts may have been built near many small rock hearths used for cooking and heating. Groups also are likely to have camped in rockshelters during the Middle and/or Late Archaic periods. The Late Archaic diet included a wide range of desert shrubs, succulents, and leafy plants; mesquite beans and other seeds were crushed in deep mortar holes in the rocks. Pictographs were first painted in sheltered areas of Hueco Tanks during the Archaic period, including abstract images and realistic hunting scenes that probably represented a spiritual relationship between predator and prey. From Mobile to More Settled LifewaysPottery came into use around 1,800 years ago in the western Trans-Pecos area, marking the beginning of the Formative period. Populations continued to increase, causing changes in settlement, diet, and technology to occur more rapidly. The Formative period is divided into the Mesilla, Doña Ana, and El Paso phases, which mark some of these major changes. Mesilla phase populations increasingly hunted the abundant jackrabbits and cottontails that inhabited the basins, adopting the bow and arrow technology around 1,200 years ago. Most of the pots that were used were undecorated El Paso Brown jars, made locally. Distinctive Mimbres Black-on-white bowls were obtained through trade with groups in southwestern New Mexico, possibly to maintain friendly relations between growing populations in both regions. Between 1,000 and 700 years ago during the Doña Ana phase, more people lived at Hueco Tanks than during any other period before or after. Across the region, settlements concentrated in similar settings on slopes below mountains, to take advantage of water that ran down the slopes after seasonal rains. A 100-year period of warm and dry weather was followed by relatively cool and wet weather for several centuries. During the middle to late Doña Ana phase, a group of rectangular houses was built in the northeast part of Hueco Tanks near patches of moist soil that were used as fields to grow corn and beans (see Village Life for more details). In another area of the Tanks, agave, sotol, and/or yucca plants were harvested with large chipped stone knives, and their root balls were rendered edible through slow roasting in rock-lined pits. A large chipped stone knife found near one pit could have been used to remove the spiny agave leaves, for it is similar to the expedient (quickly made) knives found near agave roasting pits at the Wind Canyon site. Small rock dams were built to hold the water that flowed down cracks and chutes on the rock hills during late summer rains. The three largest basins held thousands of gallons of water for extended periods, and allowed more people to stay at the Tanks for longer periods of time. During dry spells, crops may have been kept alive by carrying pots of water from the rock hills and pouring it around their roots. Although jackrabbits and cottontails were hunted at the Tanks and in the nearby basin, hunters sometimes ranged into the Hueco Mountains and down to the Rio Grande in search of game. These longer trips were required to supply meat for the large number of people who were relying on the resources of Hueco Tanks during the Doña Ana phase. The spiritual importance of water was recognized through images on the walls of rockshelters at Hueco Tanks. Most of the figures probably were painted during the Doña Ana phase, when the greatest number of people lived there. Many images appear to represent prayers for a continuing supply of life-giving water. Spiritual leaders probably directed the type and placement of images on the rocks. Some images were painted in hidden areas high on the rock hills, and apparently had greater spiritual status. Spiritual leaders also are likely to have supervised burial of the many individuals who were laid to rest at Hueco Tanks. The number of known prehistoric graves is among the highest in the region, and more may be present. The Tanks served a special role in the sacred landscape of the eastern Hueco Bolson as a place to live, obtain and pray for water, commune with the spirits, and lay cherished individuals in their final resting places. However, the plant, animal, water, and rock resources of Hueco Tanks that made it such a good place to meet the needs of daily life apparently prevented it from achieving the highly sacred status of places like Ceremonial and Picture Caves. Located 3 miles to the west, these large rockshelters were visited on pilgrimages by people from the Tanks and other areas across the region (see Ceremonial Cave), who left humble offerings of sandals and other more elaborate items. Local pottery was used in increasing quantities during the Doña Ana phase, and was made nearby but not at Hueco Tanks. Paint had first been applied to the rims of plain brown jars between 1,200 and 1,000 years ago in the late Mesilla phase. Simple designs initially were painted in black or red to produce El Paso Bichrome, and soon, both colors were used on El Paso Polychrome pottery. Groups at Hueco Tanks also obtained pots through an interregional trade network, which shifted from southwest New Mexico to south-central New Mexico during the Doña Ana phase. Small-mouthed Chupadero Black-on-white jars were imported in large numbers and used to carry water and other liquids, and Three Rivers Red-on-terracotta bowls also were obtained through trade. The network brought small amounts of pottery from more distant areas, including a beautiful pendant made from St. Johns Polychrome pottery from west-central New Mexico, and a few painted Ramos Polychrome and Villa Ahumada Polychrome pots from northern Mexico. By 700 years ago at the beginning of the El Paso phase, the small fields at Hueco Tanks were not producing enough corn and beans to sustain the growing numbers of people who lived there. Settlement shifted to areas near playas (large shallow seasonal ponds) at the base of alluvial fans, where broad areas of soil retaining subsurface moisture were available for fields. Pueblos were established 6 miles to the northwest, 7 miles to the west, and 8 miles to the south of Hueco Tanks. The pueblo to the north may have had as many as 100 rooms. Cottonwood beams used to build the roof of at least one room most likely were carried from the Tanks, the nearest source of that wood. The smaller pueblos were similar to Firecracker Pueblo and Madera Quemada, El Paso phase pueblos on the west side of the basin. Another resource that probably was transported from Hueco Tanks to the pueblos was water, carried in pots and other containers along a trail that led northwest from the Tanks toward two pueblos. Pueblo residents also made brief visits to the Tanks to hunt jackrabbits and cottontails, gather and perhaps roast small amounts of wild plants, obtain stone for grinding tools, and possibly to paint prayer petitions in the rockshelters. Although the pueblos were involved in far-flung trade networks during the El Paso phase, almost none of those exotic items were brought to Hueco Tanks. The period of abundant rainfall during the El Paso phase ended with several severe, short-term droughts around 550 years ago. People abandoned the pueblos, Hueco Tanks, and most of the region, although some groups may have remained, including the Manso and Suma who were encountered along the Rio Grande around 400 years ago. Those groups occupied brush huts and obtained food by hunting and gathering. Apache Indians slowly entered the region from the north, and by 300 years ago were using Hueco Tanks and the surrounding area as their hunting ground. They roasted agave, sotol, and/or yucca root balls in a large rock-lined pit at Hueco Tanks, and obtained water from pools on the rock hills. They added images to the growing gallery in the rockshelters, as did Kiowa and/or Comanche Indians who visited the Tanks from 200 to 100 years ago. Historic PeriodThe earliest written account of Hueco Tanks dates to in 1692, when Spanish troops stopped there before heading through a pass in the Hueco Mountains to obtain salt from sources further east. They were led by an Apache captive along a trail that connected a series of major springs and water sources between the Pecos River and the Rio Grande. The route probably had been used for centuries before Europeans and Americans arrived in the region. Mescalero Apache groups camped in or around the Tanks in 1777, having been pushed out of their home ranges in and near the Organ, Sacramento, and Sierra Blanca Mountains by Comanche Indians encroaching from the north. Acquisition of the territory by the United States in the mid-nineteenth century brought an influx of Anglo-American officials, adventurers, and settlers to El Paso. Among the first U.S. citizens to pass through the Tanks in 1849 were gold seekers heading west to California along the trail. Inscriptions like the misspelled “Watter hear”—painted in wagon wheel grease—document the importance of the reservoirs of Hueco Tanks to travelers. The trail was briefly used by the Butterfield Overland Mail stage line from 1858 to 1859; a stage station was built near the pass between the rock hills and a large prehistoric reservoir nearby may have been reinforced. After the stage line was abandoned, travelers continued to shelter inside the crumbling stone and adobe walls of the station for decades. Buffalo Soldiers and others who stopped by Hueco Tanks continued to commemorate their visits by marking their names on the rocks. In 1895, El Paso businessman Juan Armendariz purchased three sections centered on Hueco Tanks and began to use the area for ranching. Two large inscribed stones testify to Armendariz’s claim as the “dueño de este cerro” (proprietor of this hill). A few years later, Silverio Escontrias bought most of the Hueco Tanks ranch from Armendariz. By 1904 he had built an adobe house, another three-room building, and a two-room stable; the latter two buildings apparently were built with stones from the old stage station. The Escontrias family operated the cattle and horse ranch until the mid 1950s, and constructed 15 dams from rock, soil, and concrete to capture the water that ran off the hills. Modern TimesThe Escontrias family opened the Tanks to the public for recreation early in the twentieth century, and the rock hills became a popular destination and picnic ground frequented by persons from El Paso and nearby Fort Bliss. The Fort leased the ranch and used the Tanks for antiaircraft artillery training in the 1940s and 1950s, and built a small landing strip on the north side of the rock hills to launch planes towing targets. The movement to designate Hueco Tanks as a public park began in 1922, when officers of the fledgling El Paso Archaeological Society including Martin Crimmins and Otis Aultman campaigned for the site in local newspapers. In 1935, the National Park Service offered to purchase four sections around the Tanks, but Silverio Escontrias’ widow Pilar was not interested in selling. The Escontrias ranch was finally put on the market in 1956, and passed through a series of owners, some of whom developed it as a tourist attraction. Rental cabins, stables, a café, and a fake ghost town were constructed there at various times, and plans were floated for large residential and resort developments. Today, park rangers protect the archeology of this special place under the authority of the Antiquities Code of Texas. A Public Use Plan stipulates that areas containing highly significant cultural and natural resources may be visited only in groups led by trained guides, to ensure that those resources are not damaged. The Escontrias ranch house serves as the Interpretive Center for Hueco Tanks State Park and Historic Site, where visitors view an orientation video before they enter the park. Campers, hikers, rock climbers, and nature lovers continue to enjoy the recreational and educational aspects of the park, while Mescalero Apache, Kiowa, Comanche, Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, Pueblo of Isleta Indians, and other people find spiritual connections to this desert oasis. Through vigilant protection of the fragile archeological sites, rock imagery, and wildlife of Hueco Tanks, the many hidden facets of this significant place will continue to reveal secrets of desert survival to future generations.

|

|