| |

| |

| |

Two deer mandible (jaw bone) sickles

used to cut grass for roof thatch and other uses. The

fragmented and weathered one at the top was found just

outside the Kit Courson house in the work area. You

can see the characteristic sickle-sheen caused by the

build up of grass silica and polish on the better preserved

one (bottom) from Courson B. (You are looking at the

interior (inside view) of the top mandible and the exterior

of the bottom mandible.) Photos by David Hughes and

Steve Black.

|

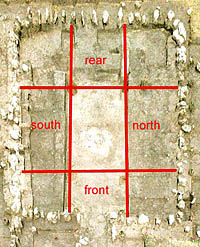

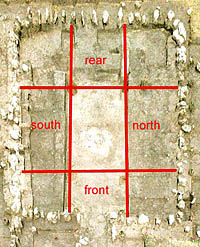

Dividing the interior of the Kit

Courson house into third's along both axes makes it

easier to talk about how each part of the house was

used. Photo and graphic by David Hughes.

|

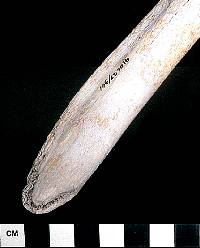

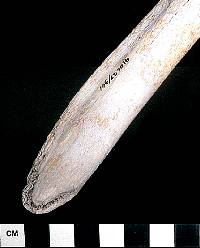

Buffalo rib pot stirrer? This bison

rib found on the floor of the central channel of the

Kit Courson house is worn on its edges and especially

at its tip. This abrasive wear pattern is consistent

with the interpretation. Photo by David Hughes.

|

Bone awls used for leatherworking

or basket-weaving found in a U-shaped channel at the

rear of the Courson B house. These are made from deer

metapodial (ankle) bones and have smoothed and polished

tips from wear. Photo by Steve Black.

|

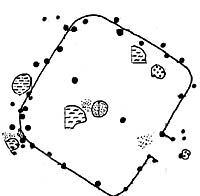

This circular pit and central hearth

are all that remains of a scooped-out pithouse found

beneath Courson B, a large, typical stone-based Buried

City house. The pithouse was small—only about 2.5

meters (8 feet) across. Photo by David Hughes.

|

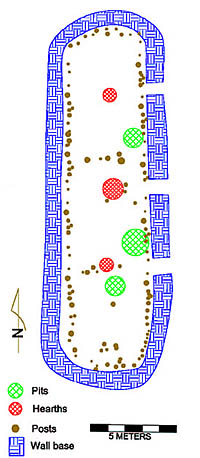

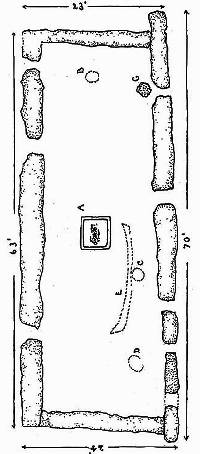

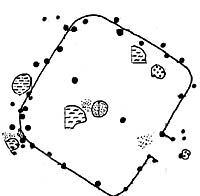

Map of small, post-lined house with

central firepit and two central support posts known

as Courson A. The inferred outline of the house is shown

as a solid line. Graphic by David Hughes. Click to see

enlarged view with more details.

|

Large storage or "cache"

pit associated with the Courson A house. These cylindrical

pits were probably used for storing corn and were later

filled with trash. Most such pits at Buried City are

smaller, about a meter in diameter. Photo by David Hughes.

|

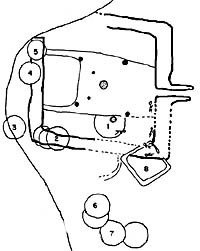

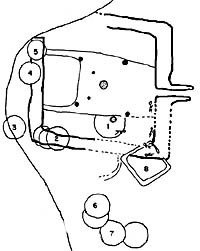

Inferred configuration of Eyerly's

Temple based mainly on recent excavations. This structure

has been dug into repeatedly since 1906, mainly by

curiosity seekers. As a result, much of the critical

evidence within and around the stone wall foundations

has been destroyed. Graphic by David Hughes.

|

Two overlapping hearths as cross-sectioned

by excavation in the southern half of the "Temple"

. The lower, cylindrical firepit (left) dates to the

main Temple occupation. The intruding basin-shaped pit

hearth (right) is part of a later occupational episode.

Photo by David Hughes.

|

|

Dark circular stains of postmolds

from large wall posts exposed inside the west wall of

the Temple by the 1988 TAS Field School. These were

found well within the room and perhaps served as roof

support posts. View looking west. Photo by David Hughes.

|

Figure 32 from Moorehead's 1931 report. It is labeled

as "west wall of Gould Ruin." A second photo

(Moorehead's Figure 34) is labeled "east wall of

Gould Ruin," but both photos show the same wall.

Click to see comparison. |

|

Life in the Kit Courson House

The Kit Courson house is the most thoroughly

investigated Buried City house. A detailed model of the house

was built by Danny Witt based on archeological documentation

and comparative data from historic earth lodges in the Northern

Plains. Although the Buried City houses may have had grass-thatch

roofs instead of being earth-covered and differed from Plains

earth lodges in other important details, the basic layout

and roof-framing may have been similar. Putting it all together—documented

details and supposition—we offer a sketch of life in the

Kit Courson house (drawing on details from other Buried City

houses as well).

The villagers would have entered the house from the east via an extended

entryway (slightly sloping down into the house), possibly

a crawl-way that was lined with posts and covered like the

house roof. The narrow entranceway minimized the amount of

snow and cold air that entered the house. Near the entrance,

but outside the house was a smaller, perhaps semi-attached

room on the southeast corner that had apparently been

added after the main house was built. This added room may

have served special purposes such as that of a menstrual room

or perhaps a mother-in-law's room. The houses of several Plains

Indian groups are known to have had such features.

Between the entryway and the attached room was

a food processing and work area where in good weather

people would have performed routine tasks like food preparation,

tool maintenance and repair, and other daily functions. (In this

area, archeologists found many deer-antler tool handles and flint-knapping

tools, a deer-jaw sickle for cutting grass, grinding stones,

and large fragments of pottery.) Weather permitting, most daily

activities and work probably took place outside the house.

When the north wind was blowing, outside work likely was done on the

leeward (protected) side of the structure or in sheltered nooks like that

created by the room addition and the entryway wall.

Entering the house, you would have stepped

over a small raised sill at the bottom of the entranceway.

When inside the house, proper, you would have been standing

in the central channel, the lowest floor level. The

sill you stepped over may have served two purposes; it probably

keep water from seeping into the room from the entranceway

and it would have been a stop for an entryway flap

door, probably made of bison hide. Such a flap door would

have been needed in the winter to trap cold air and keep it

from entering the room. Interestingly, just inside several

houses in the southeast corner of central channel, we have

found several smooth rounded stones, sometimes fragments of

grinding stones. Jack Hughes thought these served as weights

for the entryway flap door.

In the center of the central channel (which

is also the center of the house) was a fireplace or

hearth confined within a raised ring of plaster. Smoke from

fires would have exited through a hole in the roof that was

probably lined with plaster to guard against an accidental

fire (a grass-thatched roof would have been highly flammable).

Not surprisingly, numerous charcoal flecks are found in the

center of the houses surrounding the fireplace, often embedded

into the plaster. Other cooking-related detritus found in

this area includes many small (½-inch diameter or so)

fragments of pottery and small scraps of bone or mussel shell.

In the center of the channel, south of the firepit in one

house, we found a mid-portion of a buffalo rib lying against

the bench margin. The rib was worn in such a way as to suggest

it may have been used as a pot stirrer in food preparation.

Surrounding the central channel area are wide,

low, elevated platforms or benches occupying the north

and south thirds of the room and a narrower rear bench occupying

the western one-third. At the intersection of all these thirds

are the four massive posts, buried as much as 60 to 75 cm

below the lowest surface of the living floor.

In the front section of the house, the south

bench and adjacent channel area was apparently an interior

work area. At several other Buried City houses, we have found

flint-knapping debris, broken grinding stones, and heavy compaction

and wear on the floor. Most of the debris is in the central

channel, although evidence of flint knapping occurs on the

bench itself. In the Kit Courson house we found the sharp

end of a flint knife embedded in the floor—it looked

like someone had plunged a knife into the floor and then snapped

it off, leaving the broken end just below the plaster surface

of the floor in this area. In the central channel adjacent

was a large quantity of knapping debris from the same kind

and color of chert.

The front part of the north bench was

consistently cleaner than the south bench but also had some

minor knapping and bone debris (small fragments ½ to

2 inches long, possibly from meal leftovers or bone tool manufacture).

On the surface of the front-north bench areas we found fragments

of charred food items, in one instance a small pit, possibly

a storage pit, and occasional bits of pottery and tips of

bone awls.

In contrast to the front bench sections, the

central bench sections on either side of the hearth

near the center of the house are normally clean and artifact-free.

In the houses where plaster is preserved, it is heavily worn

in the central bench sections, suggesting much traffic. This

is probably where people sat while cooking and eating and

through which they passed when heading to the rear bench corners.

The rear benches, sometimes had greasy

or burned areas about 50 centimeters (20 inches) in diameter.

This could be where small warming fires (or perhaps hot stones)

were placed or perhaps the rotted remnants of a buffalo robe pile?

This pattern was very obvious at the Courson B House. In general,

the rear north and south benches (corner sections)

of Buried City houses have never produced any artifacts on

the plastered floor, and the plaster is normally well maintained

with little or no wear. These corner sections are separated

from the central rear bench by a shallow U-shaped

channel that runs along the north and south margins of

the rear bench and slopes from near the floor surface at the

west end down to the level of the central channel abutting

the main support post at that point. At the Courson B house

we found unusually complete deer metapodial (ankle bone) awls, or weaving

tools, in the channel that separates the rear bench from the

north and south benches. It is not known whether these channels

served a mundane function, such as ventilation

channels leading to small holes in the outside wall (possible

indication of such was found in one house.) Alternatively,

they could be dividers that set aside the central rear bench

area as sacred space, where ritual paraphernalia was kept.

The pattern designating the central west/rear section of houses

as sacred space (often used for altars) was widespread among

Plains Village groups.

Architectural Variation

So far we've described only a single

kind of house at Wolf Creek. These are the large, stone-based

houses of about 64 square meters (689 square feet) enclosing

a large single room that can be divided into several discrete

areas based on apparent structural features (benches, channels,

posts, etc.). Such houses are found in isolated locations,

well separated from one another, and were probably built adjacent

to one or more garden plots. These are the houses that most

observers have noted and dug into, mainly because they are

large and obvious. They appear to date in the middle to late

14th century A.D. and are limited to a few miles along Wolf

Creek, primarily on the south side of the creek.

Other styles of structures have been identified

during our studies and by the ongoing work by the University

of Oklahoma. Four different house styles have been identified

so far: single-post-wall structures, pit-houses or houses

in pits, large single-room stone foundation houses, and one

extremely large, multi-roomed, stone-based house. Design variation

in the houses in a community is accepted as the norm

today, yet archeologists seem to assume that, in the past,

people made all their buildings in the same way in each area.

Much of the variation we see along Wolf Creek may be simply

the range of seasonal variation within a single community.

Some structures may have been relatively light and porous

for use in mild weather while others (the larger stone-based

houses) were durable and resistant for use during inclement

weather. The use of summer arbors and more substantial houses

for winter is well documented by archeology and ethnohistory

throughout the Southeastern U.S. It is, however, also possible

that some of the variation seen along Wolf Creek may have

developed over time; as more houses are excavated and dated,

this idea can be evaluated. Regardless of what the source

of the architectural variation may be, the differences are

quite real.

The Courson A house shows the first variation

in architectural style. It is a small house with walls made

of a single row of posts, a central firepit, and two central

support posts. The floor is irregular and lacks clear-cut

evidence of plastering or smoothing. The entryway was probably

to the southeast, although there was no obvious entranceway.

Work areas associated with the house may have surrounded it,

with a prominent work area west of the house, probably even

then on or near the bluff overlooking Wolf Creek. This house

was probably used in the mid to late 1200s. The finding of

small pieces of stick-impressed daub suggests that the house's

walls may have been constructed of wattle and daub: vertical

posts set in the ground, then woven with thin limbs, vines,

and other pliable substances, and then the whole thing plastered

with a layer of mud. There were no rocks in the base of the

walls.

The Courson B site contained a large

typical Buried City house with stone-base walls that were underlain

by two pits that had features reminiscent of pithouses. There

were no obvious postholes associated with them, but their

shallow basin form (about 2.5 meters in diameter) and

a hearth in one, suggest they may have been small pithouses. Radiocarbon

dates suggest the pithouses were in use during the early 1200s,

slightly earlier than the overlying, large, stone-based house at Courson

B. Both possible pithouses had been filled with trash and

then after the passage of some time, the large stone-based

house at Courson B was built over them.

A third house style was also documented at Courson B, a small square structure with no central channel, no

formalized entry, and only a single line of postholes associated

with a foundation of single rocks. No datable features (firepits, charred posts, etc.)

were found in association with this structure, so we only know

that it dates after the large stone-based house and pre-dates

the terminal event at the site: a mass burial covered by a

rock cairn burial.

Eyerly's "Temple"

The most unusual and atypical "house"

at the Buried City is the one Eyerly called the "Temple"

and Moorehead labeled Gould Ruin. While it doesn't

seem to have been a temple in any meaningful sense, Eyerly's

Temple is almost three times the size of any other prehistoric

structure along Wolf Creek.

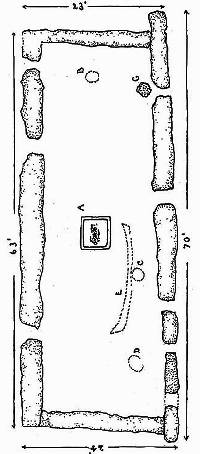

The basic dimensions of Eyerly's Temple have

been known since the late 19th century: The long-axis of the

structure is oriented 30° east of north and extends for

about 22 meters (72 feet). It was some 7-8 meters (23 to 26

feet) wide (reports vary and some details were obscured or destroyed

by repeated digging). Observations and opinions of the building

varied, depending upon the observer and his prejudices. Eyerly

suggested the structure was a burial mound. Moorehead defined

it as a multiple-room structure with a central burial chamber.

Our work in 1988-1990 confirmed neither of these, but produced

a third alternative still and left us with far more questions

than it did answers.

Our work at Eyerly's Temple was limited largely

to exploring the past archeological and less formal digs

in the site and only secondarily allowed us an opportunity

to investigate the prehistoric site and its contents. By clearing

the disturbed matrix from previous excavations, tidying up

the results, and doing some limited and partial exploration of the

features previous workers didn't identify or explore, we hoped

to gain insights into the structure while limiting our own

damage. This limited objective was intentional since we will

probably never see another Buried City building quite like

Eyerly's Temple.

In practice, our intended approach was difficult

to accomplish because, even when records of past work existed,

they didn't seem to accurately reflect the situation on the

ground. T. L. Eyerly mentions only that his crew dug into this structure

a little. Correspondence from Warren Moorehead to Fred Sterns suggests

that Sterns spent some time excavating at the Temple but,

without Sterns's notes and photographs, we do not know where

he worked, how much he dug, or what he recovered. Franklin

mentioned doing "some work" there, but didn't provide

any maps or photographs showing exactly what he did.

With Moorehead's work in 1920 we are on somewhat

firmer ground, as he published sketches of his work in 1920

and there are some photographs. Moorehead noted that he paid

Sam Handley to backfill the excavations at the end of the

season. During the 1990 season, we began to encounter bits

of barbed wire intertwined with the rocks of the Temple and

other puzzling occurances. Fortunately, a long-time local

resident informed us that Handley did not backfill Moorehead's

trenches, but had instead left them open for years so that

the locals could see what they looked like. Handley used strands

of barbed wire to keep the rocks from collapsing into the

open trenches and, according to the informant, from time-to-time

restacked the rocks after they had collapsed.

Finally, there are some errors in the published

record. Moorehead notes four openings or doorways in the west

wall and five in the east wall and refers the reader to his

Figures 32 and 34 for evidence. Close examination of these

photographs shows them to be the same wall viewed from slightly

different perspectives. Fortunately, we were able to secure

a copy of Moorehead's original field notes from the Peabody

Museum in Andover, Massachusetts and these plus other sources

provided a somewhat better guide his work.

The south wall of the Temple may have been destroyed

before Moorehead arrived—he does not show firm rock alignments

marking its position. Second, he notes at one point that near

the south end "of this [central to the ruin] trench we

found a fragmentary bunched burial, down 20 inches—no skull

and no large bones." His field notes discuss at length

his difficulty in finding qualified labor and eventual decision

to use a Fresno scraper and mule team (predecessor to the

modern road grader) to excavate the trenches. This might explain

the partial bundle burial containing only a upper torso and

skull that we found in a similar location. Moorehead's expedient

use of mechanical (or mule-powered!) excavation may have limited

what he could observe in his excavations.

During the 1988 and 1990 work, we found sufficient

features to suggest that Moorehead's (and everyone else's)

work did not finally reach the primary occupation floor of

Eyerly's Temple except where the walls were trenched through

the house floor. We were able to identify postmolds, storage

and cache pits, firepits, and some other features from the

prehistoric construction as well as numerous features from

known and unknown historic excavators.

The walls of the house appear to have been lined

with posts set about 25 to 40 cm (10-15 inches) inside the

stone facing of the wall. In the geometric center of the structure

was a very large firepit almost 75 centimeters (30 inches)

in diameter and about the same in depth. Flanking this firepit

were six large postmolds that probably represent the primary

roof support posts of the structure. In the center of the

southern half of the house was a cylindrical firepit of about

30 to 50 centimeters (12-20 inches) in diameter that was bracketed

on the east and west by two postmolds 10 to 15 centimeters

(4-6 inches) in diameter. Scattered throughout the building

were the cylindrical trash or cache pits about a meter in

diameter, which seem so characteristic of the Buried City.

Moorehead reported several openings in the east

and west walls of the structure, but because of the extreme

disturbance of the stone walls since Moorehead's work, we

could neither confirm nor deny his observation. What openings

we did find seemed to extend irregularly beyond the structure

as though they represent "pothole" or informal excavation

pits more than architectural elements. Along the east wall

are three areas that might represent possible architectural

openings. These seem to be aligned with the two confirmed

firepits and possibly a third that Moorehead found.

Eyerly's Temple represents the most

unusual structure in the Buried City. Consider, however,

that it seems to contain 3 fireplaces, 3 sets of center posts,

and is roughly 3 times the size of the "typical"

stone-based house. Perhaps the Temple was a large tripartite

house, holding 2 or 3 families under a single roof with informal

or light partition walls dividing the space into three units:

north, central, and south. Since the central unit has a substantially

larger hearth than the north or south, then perhaps it served

as a community room for two related, extended families or lineages

occupying the north and south areas. If complete excavation

of the structure is ever undertaken, this hypothesis would

certainly be worthy of exploration.

Eyerly's Temple, like most Buried City structures,

probably had a complicated history of use that we will never

be able to fully sort out because of how it has been treated

in historic times. The overlapping hearths show there were

at least two occupational periods. But Eyerly surely thought

it was a burial mound because he found burials in the upper,

mounded part as it appeared in 1906. The mounded earth probably

represents the decayed earth-filled upper walls and possibly

the earth-covered roof of the "big house." Thus,

the burials Eyerly dug into were probably interred long after

the big house had fallen into ruin, perhaps even centuries

later by unrelated Native American peoples.

|

|

|

|

|

Apparent work area outside Kit Courson

house on the side sheltered from the wind during the winter. This area

has produced many deer-antler tool handles and flint-knapping

tools, a deer-jaw sickle for cutting grass, grinding

stones and large fragments of pottery. Photo by David

Hughes.

|

Metate or grinding basin from the

Kit Courson house. It measures about 18 by 13 inches

and was probably used in conjunction with a mano (hand

stone) to grind corn.

|

Central firepit or hearth in the

Kit Courson house. Notice several things. The firepit

is small, but deep and could have held a substantial

bed of coals. The area around the firepit is stained

by charcoal and ash. Less obvious is the raised plaster

rim that surrounds the firepit and helped contain it.

The small depressed area where the tape measure is (see

enlarged view) could be a food preparation area. In

the upper left corner of the photo is a buffalo rib

thought to have been used as a pot stirrer (see separate

photo). Photo by David Hughes.

|

Plastered U-shaped channel perpendicular

to rear wall of Kit Courson house. View east from rear

wall toward the entrance. It is not known whether such

channels served a mundane function, such as perhaps

being ventilation channels leading to small holes in

the outside wall (a possible indication of such was

found in one house.) Alternatively, they could be dividers

that set aside the central rear bench area as a sacred

space, where ritual paraphernalia was kept. Photo by

David Hughes.

|

| |

Jack Hughes stands just outside the

apparent doorway of Courson A, a rectangular surface

house. This single post-wall house had two central support

posts, and central hearth, and two exterior trash-filled

storage pits. The interior dimensions were about 4 by

4.6 meters (13 by 15 feet). Photo by Madeline Jeffress,

TAS.

|

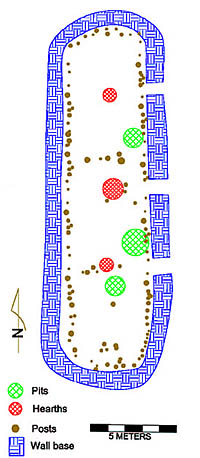

Map of Courson B site showing large

typical Buried City house with stone-based walls, storage

pits, two possible pithouses, and a small square house.

Graphic by David Hughes. Click to see enlarged view

with more details.

|

View northwest of excavations of

Eyerly's "Temple" in progress in 1987. Photo

by David Hughes.

|

Eyerly's" Temple" is almost

three times the size of any other structure at Buried

City. It may have been a three-room structure, having

three doorways, three hearths, and, possibly two interior

walls. Photo by David Hughes. |

Gould Ruin drawing from Moorehead, 1931. Click to see

enlarged view with legend. |

Detail of the relatively undisturbed

west wall of the temple structure. North is at the top.This

is probably what the whole thing looked like when Eyerly

first exposed it in 1906. Note the vertical slabs on

the interior (to left) of the wall with rubble and boulder

fill about a meter thick and then more vertical slabs

on the exterior or western face of the wall. Photo

by David Hughes. |

Overhead photograph of Eyerly's Temple with overlayed

features. Click to see enlarged drawing with legend and

extra large final photo without overlay. Photograph and

graphic by David Hughes.

|

|