Spring time flowers along Wolf Creek following

a wet spring. Such conditions would have meant good years

for the corn planted by Plains Villagers. Photo by David Hughes.

Click image to enlarge

|

These bison ribs were found cached together

in the Courson B house. Several of them have a row of parallel

notches. These may be rasps used as musical instruments. Photo

by David Hughes.

|

Closeup of an Antelope Creek rasp similar

to those found at Buried City (although this one is made on

a limb bone rather than a rib). Rasps were presumably used

as musical instruments by stroking the notched bone with a

hardwood stick. Notice the polish along the notched edge.

From the collections of the Panhandle Plains Historical Museum,

photo by Steve Black.

|

Bison tibia (lower leg bone) tools used

to tip digging sticks. From the Courson Buried City collection,

photo by Steve Black.

|

Closeup of characteristic wear patterns

present on bison tibia tools including edge rounding, smoothing,

and polish from contact with soil. From the Courson Buried

City collection, photo by Steve Black.

|

Tortoise shell. Shells like these were

used for rattles, bowls, and paint containers by various Plains

Indian groups. Photo by David Hughes.

|

Shell and bone artifacts from Buried City.

The two bone fragments have been shaped to form sharp points

and may have been used to stretch holes in leather during

lacing. Native mussel (freshwater clam) shell was notched,

cut, and drilled to create pendants. Photo by David Hughes.

|

Replica of cordmarked jar with an incised

decoration by Alvin Lynn. From the Courson Buried City collection,

photo by Steve Black.

|

Buried City jar with smoothed exterior

surface. Photo by David Hughes,

|

| |

Stone drills with delicate bits made of

Alibates flint. Photo by David Hughes.

|

Hide scrapers made of Alibates flint. Photo

by David Hughes.

|

Obsidian arrow points and tool fragments

from Buried City. Such materials were traded from New Mexico

and other distant sources. From the Courson Buried City collection,

photo by Steve Black.

|

|

The people of the Buried City were gardeners, hunters,

and foragers. We know they raised corn and we strongly suspect

they also grew other crops like beans, squash, and chili peppers,

although these don't preserve well archeologically. Crops were

probably planted in the low-lying swales between houses and along

the valley floor (floodplain). During especially wet years when

floodwater occasionally inundated the valley floor, simple diversion

dams (lines of stones and/or rows of bushes) across the swales would

have kept the fields wet enough for good crops. This strategy is

similar to the Ak-Chin dryland farming technique used in

northwest Mexico and southern Arizona by various groups including

the Pima and Tohono O'odham people (who are collectively known as

the Ak-Chin, from the O'odham word meaning "place where the

wash loses itself in the sand or ground"). During dry years

when the swale crops might not have been successful, those planted

in the valley floors would have had sufficient moisture to grow.

The abundant bison bone on the Buried City sites shows

that buffalo hunting was important. Buffalo provided meat

and many other useful products including hides and bones for tools.

We also find deer bones and antlers as tools so they were hunting

white-tail deer in the local area. (Antelope and deer bones are

quite similar and it is likely that antelope were also killed.)

In addition to large mammals, the bones of smaller critters are common

in the sites including those of cottontail, jackrabbit, turtles,

and frogs, as well as sunfish bones, drum fish teeth and abundant

freshwater mussels.

The vegetation in the area was diverse and the people

used western red-heart cedar as main support posts for the houses,

plum and winged elm wood for the wall posts, and lashed them all together

with willow withes, grape vines, and twigs of plum and elm. The

hearths contained charred wood from oak, elm, juniper, plum, cottonwood,

and other species of trees. One visitor suggested that the oak-charcoal

layers in the firepits may represent winter-time use, while the

cottonwood charcoal and ash probably represent summer fires, the

difference being whether you want a long-term fire to keep the house

warm all night or a quick fire just to heat a meal.

The primary gardening tool was a digging stick

with a bone tip made from a bison tibia (lower leg bone—which

is thick and tough). Such tools had wooden handles inserted into

the end of the tibia (which had been cut or broken out) and may

have been used as hoes or as straight digging sticks/dibbles—sort

of like a narrow-bladed trenching shovel. Bison scapulae (shoulder

blades) may also have been used to move loose dirt and for smoothing

plastered surfaces. No stone hoes or other digging tools have been

identified at Buried City sites.

|

|

|

|

Artist's depiction of the

use of a bison tibia digging stick or "dibble." It

may have been used similarly as a shovel as well. Drawing by

Wade Parsons.

|

Artist's depiction of the

use of a bison tibia hoe. Drawing by Wade Parsons.

|

Bone was used for a variety of tools other

than for digging. We find bone awls and needles for making basketry

and clothing, deer jaws used as sickles for cutting grass, deer

antlers used for knapping flint, bison ribs that may have been used

as pot-stirrers, and abundant grooved or notched bison ribs that

may have been used as musical rasps, tally sticks, or for other

purposes. At one site, several notched ribs were found laying together,

as if for some particular social purpose beyond the mundane.

Marine shells like olivella and others from

the Gulf of California were used for ornaments like beads

and pendants. Native mussel shells (freshwater clam) were also

made into pendants by notching, cutting, and drilling holes into them. Some of the

native mussel shell may also have been used as pottery scraping

and smoothing tools and for spoons.

Although rare, turquoise ornaments are known

from Buried City. The source area for these lies to the west in

New Mexico. From the Courson Buried City collection, photo by Steve

Black.

Food was cooked and stored in locally made pottery

vessels. Buried City pottery was generally globular and about

8 to 12 inches in diameter, volleyball to basketball size, with

a constricted neck and a vertical rim. What sets Buried City pottery

apart from the similar-shaped pottery of the Antelope Creek area

(which is called Borger Cordmarked) is the abundant decoration of

the rims and the variety of surface finishes. About one-third of

the Buried City rim sherds include a variety of decorations like

fingernail impressions or gouging, impression of the rims with tools

like mussel shell, and thickening of the upper rim to form a collar.

We also see various incisions around the rim on the collar. In addition

to decorated rims, the pottery also includes cordmarked and smoothed

rims. Body sherds are most often cordmarked, but some seem to have been

textured with some other kind of tool, and still others have been

carefully smoothed. This kind of decoration on rim sherds and variation

in surface finish is more often found on Central Plains Tradition

sites (in Kansas and further north) than it is in Southern Plains

village sites.

Food was prepared in many ways including grinding,

and we find the remains of worn-out grinding slabs or metates in

all the sites as well as the hand stones or manos that were used

with them.

|

|

|

|

View from top of rim section

of large cordmarked olla, or jar, with a scalloped rim formed by

finger impressions. From the Courson Buried City collection,

photo by Steve Black.

|

Replica of Buried City jar

by Alvin Lynn. From the Courson Buried City collection, photo

by Steve Black.

|

Tools for hunting, processing meat and hides,

and for other purposes were made of Alibates flint and other cherts

and jaspers. Despite the nearness of Buried City to the Alibates

Flint Quarries, there is little evidence of substantial access to

Alibates flint on Buried City sites. Brown jasper from western Kansas

makes up a measurable percentage of the tools, as does Tecovas jasper

from the southern Texas Panhandle. Additional evidence of limited

contact with the Alibates quarries is that almost all of the tools

find have been extensively re-worked, worn-out, and recycled prior

to discard and even the flint-knapping debris is extremely small

and almost any flake that could be held between two fingers shows

edge damage from use as a scraping or cutting tool.

The styles of stone tools are fairly typical for the

Southern Plains people of the 12th and 13th century. These include

various kinds of drills or perforators, diamond-shaped beveled knives

sometimes called Harahey knives, and side-notched, unnotched, and

side- and base-notched arrow points. For arrows to fly true and

arrive with enough impact to take down a bison or with enough accuracy for a

deer, they must be carefully worked. We see some evidence of the

care in arrow manufacture in the form of a bison rib shaft straightener

or shaft wrench and a grooved abrader for smoothing the shafts once

they were straightened

As rich as the material we have may seem, most of

the goods owned by the people of the Buried City didn't survive the

ravages of time. We know from the needles, awls, and other tools

that they probably had clothing, bags, boxes, and other materials

made of hides, probably had baskets, mats, and sandals of woven

goods, and many objects and tools of wood and other perishable remains

which don't normally preserve.

|

Fragment of a charred corn cob found at

Buried City. Photo by David Hughes.

|

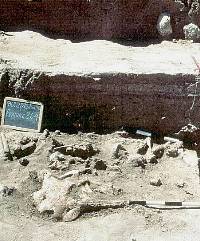

This pit filled with bison bone was found

under the Courson B house. The pit was an old pithouse depression

used for a trash dump prior to the building of the typical

Buried City house. All parts of a bison were found in this

pit, including the skull, indicating the animal(s) must have

been killed close by. Photo by David Hughes.

|

Bison rib fragment about 7 inches long

with regular notches. Function unknown. Photo by David Hughes.

|

End-on view of the beveled tip of bison

tibia tool. From the Courson Buried City collection, photo

by Steve Black.

|

Closeup of bison tibia digging tool showing

polish. From the Courson Buried City collection, photo by

Steve Black.

|

Marine shells (upper two on right and lower

right) like olivella and others from the Gulf of California

were used for ornaments like beads and pendants. Some of the

native mussel shell may also have been used as pottery-smoothing

and scraping tools and for spoons.

|

Large section of cordmarked jar with an

incised decoration. From the Courson Buried City collection,

photo by Steve Black.

|

What sets Buried City pottery apart from

the similarly shaped pottery of the Antelope Creek area is

the abundant decoration of the rims and the variety of surface

finishes. Photo by David Hughes.

|

Rim section of large cordmarked olla or

jar with a scalloped rim formed by finger impressions. From

the Courson Buried City collection, photo by Steve Black.

|

Bone arrow-shaft "wrench," used

to straighten arrow shafts. From the Courson Buried City collection,

photo by Steve Black.

|

Knives and knife fragments made of Alibates

flint. Photo by David Hughes.

|

|

|

|