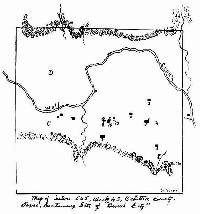

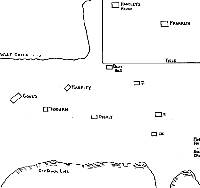

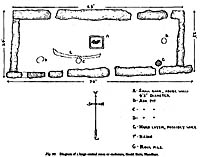

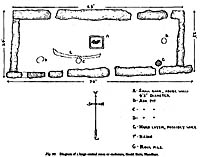

Moorehead's plan of the Gould Ruin,

also known as Eyerly's Temple. From Moorehead, 1931. |

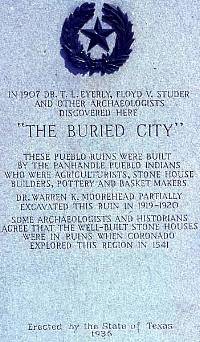

Tom Ellzey grew up on a ranch along

Wolf Creek. As a graduate student at the University

of Texas at Austin in mid-1960s, Ellzey carried out

additional explorations at the Handley Ruin identified

by Moorehead. The granite historical marker for Buried

City seen in this picture is apparently located on the

Handley Ruin. Unfortunately, the results of Ellzey's

work have never been fully reported. Photo by Chris

Lintz.

|

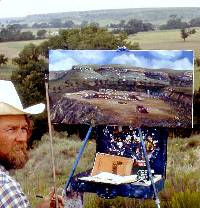

Landowner Harold Courson at the 1987

TAS field school at Buried City.

|

TAS crew in 1987.

|

Excavation of a pithouse underway

in the Courson D area at Buried City in August, 2003.

Photo by David Hughes.

|

Pithouse excavated in August, 2003

at the Courson D site in the Buried City settlement

zone by the University of Oklahama. The feature identifications

are clearly labeled. Photo and graphic by Scott Brosowske.

|

|

Although his Arkansas River Valley explorations

were completed in 1921, Moorehead was soon distracted by work

at several major mound sites including Cahokia and Etowah,

and the results of his investigations of the Buried City languished

until 1931 when his Archeology of the Arkansas River Valley

was published. He remained at Phillips Academy until his retirement

in 1938, shortly before his death. Moorehead is said to have

been a sensitive and retiring person who took great umbrage

at perceived (or actual) slights and professional criticisms.

In an era of growing professionalization of the discipline

of archeology, Warren King Moorehead was one of the last of

the "old school" of 19th century, self-trained archeologists.

The friendly relations between Studer, also

a largely self-taught archeologist, and Moorehead continued

for many years after completion of these early investigations.

Correspondence between them suggests that Moorehead may have

played a significant role in encouraging Studer's participation

in the founding of the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum.

Studer continued his interest in archeology through this new

forum and was instrumental in arranging Works Progress Administration

excavation of many archeological sites in the Texas Panhandle

through the 1930s.

The creation of Lake Fryer on Wolf Creek

not far downstream from Buried City in 1938 undoubtedly destroyed

many Plains Village houses. The area was not studied prior

to its inundation.

Following Moorehead's investigations, no archeological

research was carried out along Wolf Creek until the mid-1960s

when Tom Ellzey, who had been raised on Wolf Creek

and was then a graduate student at the University of Texas,

undertook to explore the Handley Ruin identified by Moorehead.

Ellzey's investigations were conducted because of his interest

in the area and increasing interest in anthropology and archeology

as a profession. He also recorded several other sites in the

immediate vicinity. No final report of Ellzey's investigations

has ever been published.

Sam Handley (who sometimes spelled

his name Handly) had owned the Buried City since the early

part of the nineteen-teens. During the past few decades of

his life (1950s and 1960s), Handley opened his ranch on Wolf

Creek to the public. For a small daily fee, local people could

come picnic, fish, and hunt or dig for artifacts. As a result,

virtually all of the house ruins obvious on the surface were

dug into repeatedly and many artifacts were removed.

In the early 1980s Perryton resident and

oil man Harold Courson purchased the old Handley Ranch,

including the Buried City and related archeological sites,

from the estate of Sam Handley. One of the reasons Courson

purchased the property was that he knew of its significance

and the local awareness of its importance and, paraphrasing

his own words, he wanted to give something back to the county

that had given so much to him. Harold Courson and son L. Kirk

Courson devised a development plan for the ranch's livestock,

renovation of its historic structures, and archeological investigation.

In 1985, Kirk Courson called archeologist David Hughes (author of this exhibit) to inquire about salvaging two Buried

City sites that were rapidly eroding into Wolf Creek on the

newly acquired ranch. (Each of the major concentrations of

ruins are now considered separate sites.) Hughes began investigation

of sites, dubbed Courson A and Courson B, in the summer of

1985 with a small professional crew supplemented by Perryton

High School students. Because of the size of the effort and

the potential remaining in Buried City studies, the Courson

family invited Hughes back in 1986 and a more comprehensive

investigation was begun to complete the work at Courson B and

expose the house at Kit Courson, a third locality.

Because of public interest and the archeological

potential discovered in these heavily disturbed sites, the

Courson family and Hughes invited the Texas Archeological

Society (TAS) to hold their field school at the Buried City

in 1987 and 1988. Hundreds of volunteers from all over Texas

and many surrounding states came to the Wolf Creek Valley

to help secure information about this unique archeological

area. TAS investigations completed the work at Courson A,

Courson B, the Kit Courson Site, two additional localities,

Courson C and Courson D, and began new explorations of "Eyerly's

Temple," the structure Moorehead called the Gould Ruin.

The final major field season Hughes directed

was in the summer of 1990 when Wichita State University held a 3-month field school to complete preliminary evaluation

of the unusual Eyerly's Temple in the original Buried City

site area.

Analysis of these findings and preparation of

the reports is continuing under the direction of Hughes at

Wichita State University in Wichita, Kansas. When all analysis

is completed, all collections and photographs will be returned

to the Courson family who plans to make the information available

through a public museum and interpretation in the area.

In 2000, a new round of investigations at Buried

City began under the direction of Scott Brosowske,

a Ph.D. student at the University of Oklahoma. Brosowske was

invited by the Courson family to carry out geophysical survey

work along Wolf Creek to search for buried structural remains.

A consulting firm, Archaeophysics LLC, carried out the survey

using several different sensing devices including a soil resistance

meter, a gradiometer, and a ground penetrating radar. Each of these devices detects anomalies

(irregularities) in the soil such as those caused by the excavation

of pits, fired surfaces, and buried rock alignments. Among

the numerous anomalies were many the team thought were likely

the signatures of cultural patterns, such as trash pits and

pithouses.

The following year (2001), Brosowske, aided

by avocational archeologists, began to "ground truth"

the geophysical data, meaning they began to sink test pits

in and around the anomalies they felt were most promising.

The initial results were very encouraging, but the need for more extensive excavation was

obvious. So in the summer of

2003, Brosowske and fellow University of Oklahoma archeologist

Susan C. Vehik returned to the area with an archeological

field school aided again by volunteer archeologists.

The Oklahoma team excavated two areas and in

both cases came down on deeply buried pithouses that look

very different from the stone-based houses built on the surface

that are considered typical of Buried City. The analysis is

just beginning, but the artifact assemblage seems to be very

similar to that found in the stone-based houses. In other words,

Plains Villagers were also living in pithouses. It is not

yet known whether, as Brosowske suspects, some of the pithouses

date a century or two earlier than the stone-based houses.

But what is obvious is that the history of the Buried City

settlement is much more complex and interesting than has been

known for almost a century.

|

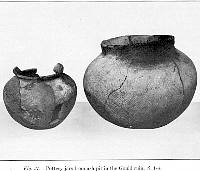

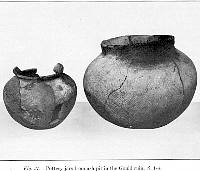

Cordmarked jars from the Gould Ruin.

From Moorehead, 1931.

|

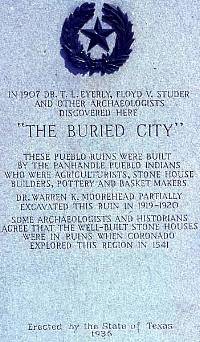

Buried City historical marker erected

by the State of Texas in 1936. Photo by Chris Lintz.

|

TAS members at work in 1987.

|

TAS crew water screening. This technique

allowed improved recovery of small bones and other tell-tale

evidence. Photo by David Hughes.

|

|

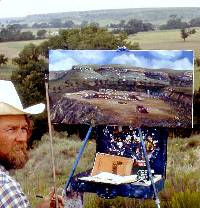

Artist Charles Becker painting scene

of TAS excavations in 1987. Photo by Wallace Williams. |

Scott Brosowske pauses to discuss

his excavation strategy. As the accompanying photo shows,

in this excavation area, a deeply buried pithouse was

found. Photo by David Hughes.

|

|