It's banks lined with pecan, oak, and black walnut trees,

the spring-fed San Saba river winds lazily through the

hill country, connecting the sites of the Spanish Colonial

mission and presidio to the nineteenth-century army post,

Fort McKavett.

Photo by Susan Dial.

Click images to enlarge

|

Tools of the surveyor. U. S. Army

engineers mapped routes across the state for travelers,

and placed garrisons in strategic locations to help

protect them. This selection of period surveying equipment

and maps is displayed at Fort Concho NHL, San Angelo.

|

The clear waters of Government Springs

provided an ample water supply for the fort, then as

now. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Amid brightly blooming cactus, limestone

cobbles—a hallmark of the Edwards Plateau—reflect

the sunlight. The white stone was quarried by soldiers

for building post structures. Quarry area is visible

in the distance. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Built in 1856, the commanding officer's

quarters stands in ruin today. In addition to providing

residence for the commanding officer, his family, and

servants, it served as guest quarters for visiting officers,

including William T. Sherman, general of the army, and

Gen. Phillip Sheridan. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and

Wildlife Department. View

1936 photo of building before it burned. |

A cornucopia of supplies. A typical

officer's field pack weighed 76 pounds when full and

included "hard tack" biscuits, canned goods,

hunting knife, "mucket," and a cone of brown

sugar. John Cobb collection.

|

|

Although it was falling into ruin by the mid-1800s,

the abandoned Spanish presidio on the upper San Saba River

occupied a prominent place in the strategies of American soldiers

planning the defense of the Anglo-Texan frontier.

Albert Sidney Johnston, secretary of war of

the Republic of Texas, had proposed placing a garrison at

the "old Spanish fort" as part of his plan for a

line of military posts running from the Red River to the Nueces.

Texas never implemented Johnston's plan, but officers of the

United States Army would later look favorably on the presidio's

central location on the Edwards Plateau.

The end of the United States' war with Mexico

in 1848 brought two issues of military strategy to convergence

in the Hill Country. The first was the protection of the frontier

settlements from raids by Comanche and Kiowa Indians. The

second was the protection of westering travelers headed for

the gold fields of California by way of El Paso.

The discovery of gold in California set off

a flurry of exploration for transcontinental travel routes.

Overland passage from St. Louis required crossing the uninhabited

Great Plains—or Great American Desert, as the region

was denominated on maps of the time—with their twin dangers

of Indian attack and winter blizzards. The sea route, around

the southern tip of South America, looked on paper to be even

more time-consuming than it was in practice, and was expensive

in any event.

Travel from New Orleans to Austin or San Antonio

seemed easy enough. Passage from there, through El Paso to

southern California, would be free of snow. The only thing

lacking was development of a route that was safe from hostile

Indians.

The veteran ranger and surveyor Jack Hays conducted

an ill-fated exploration west from San Antonio in 1848 that

was followed the next year by the more successful venture

of Hays' fellow ranger, John S. "Rip" Ford, and

U.S. Indian agent Robert Neighbors. Their effort began north

of Austin and proceeded west, following the Concho River from

its confluence with the Colorado, into the Trans-Pecos region,

then west to El Paso. The Ford-Neighbors expedition returned

by way of the Concho, San Saba, and Llano rivers, then through

Fredericksburg and into San Antonio.

The U.S. Army was following the same train

of thought, and almost the same schedule, as the civilian

explorers. Departing San Antonio, lieutenants W.H.C. Whiting

and William F. Smith traveled through Fredericksburg to the

San Saba River, then west through the Trans-Pecos. When they

returned, Whiting recommended locating a garrison of mounted

troops at "old Fort San Saba." In 1851, Brevet Major

General Persifor Smith, commanding U.S. Army forces in Texas,

ordered the construction of a post on the San Saba "at

the headsprings of that river near the El Paso road."

Selection of an 8th Infantry headquarters on

the San Saba proved unsatisfactory. The regiment arrived at

the headwaters in March, 1852, and established camp as ordered.

The site was on a small hill near a pond of "permanent"

water. Although construction was begun on a lime kiln and

bakery, the camp was soon moved two miles downstream when

the pond became stagnant.

The new location was at first referred to as

the "Camp on the San Saba" or "Post on the

San Saba." In October, it was renamed Camp McKavett—and

thereafter Fort McKavett—in honor of Captain Henry McKavett

of the 8th Infantry, who had served meritoriously in the Mexican

War and been killed at Monterrey in 1846.

Five companies of the 8th Infantry initially

were assigned to the post, and they set about constructing

permanent buildings: five infantrymen's barracks, kitchens

used temporarily as officers quarters, a hospital, and a quartermaster's

storehouse. These were erected around a square parade ground.

Each company was responsible for constructing its own quarters,

and those of its officers.

Limestone was quarried nearby for building

foundations and walls, and was burned—probably in the

kiln at the original location—for mortar. Oak and pecan

logs were used for construction of some buildings in the jacal,

or picket, style. At first, there was no lumber for floors

or doors, nor glass for windows. The required materials were

transported from Fredericksburg in later years.

The post was improved substantially through

the mid-1850s. The new construction included two-story quarters

for the commanding officer and one-story barracks for other

officers, adjutant's office, guardhouse, new bakery and kitchens,

and laundresses' quarters.

Military operations at and around Fort McKavett

reflected the evolution of the army's strategy of frontier

defense in the 1850s. On an inspection tour in August, 1853,

Colonel W. G. Freeman found Fort McKavett garrisoned by one

company of mounted infantry—46 men with only 30 serviceable

horses, "wretchedly equipped." The company's request

for needed equipment had been properly rejected, said Colonel

Freeman, because, "it is now everywhere conceded that

the experiment of mounting infantry has not been successful."

|

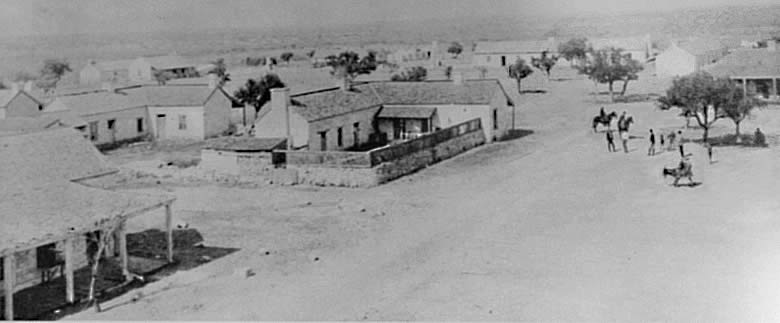

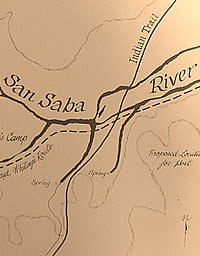

Lt. W. H. C. Whiting of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, along with Lt. William F. Smith, surveyed the route for the "lower

road"for emigrants traveling from San Antonio to

El Paso and on to the gold fields of California. To protect

those traversing the" upper road" through Fredericksburg,

he recommended locating a garrison of mounted troops on

the San Saba river.

|

The proposed location for the fort indicates its strategic

location near an Indian trail as well as the upper road

to San Antonio, marked on the map as Lt. Whiting's route.

Map courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. |

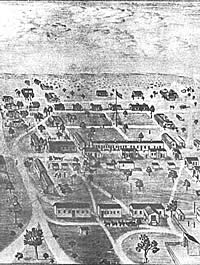

Sketch of Fort McKavett, with river winding below, circa

1861. Image courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

Kiln to make lime, used in plaster for the buildings as

well as in privies at the fort. Limestone rock was placed

in the kiln and heated from a wood fire below. The three-

to four- day reduction process included burning, cooling

and slaking the material before the powdery lime was ready

for use. Photo by Susan Dial. |

The second post hospital, completed in 1874, replaced

a smaller structure from the 1850s. The new structure,

set well apart from other buildings at the fort to curtail

windborne germs and odors, housed the offices of the surgeon

as well as a wing for patients. The building to left is

the dead house, or morgue. Photo by Steve Dial. |

The post schoolhouse (on right) was

constructed in 1874 to provide an education for enlisted

men, particularly the freed slaves who enlisted in the

Army after the Civil War. Taught frequently by the post

chaplain, the men learned to read and write in classes

at the end of the work day. On left are lieutenants'

quarters.

|

|