|

||||||||

|

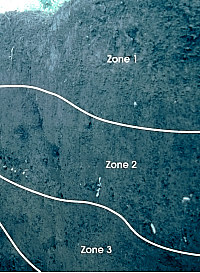

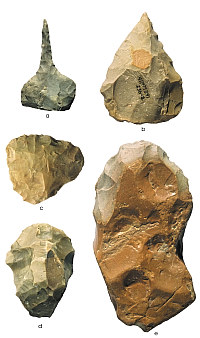

The planned replacement of a highway bridge spanning part of the wide, nearly flat Little River floodplain led to the archeological investigation of the J. B. White site and two other nearby prehistoric sites. This section explains how the archeological research unfolded in advance of bridge construction. All planned road construction activities by the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) are evaluated for their potential to affect sites important to the history and prehistory of the United States. Staff archeologists from TxDOT's Archeological Studies Program of the Environmental Affairs Division do these initial evaluations. TxDOT examined the bridge replacement project area. They noted that the part of the project area within the river floodplain was cut by many sloughs and abandoned channels of the river. These kinds of natural features suggest a long history of intermittent flooding. During such floods, the river sometimes changes course and cuts a new channel leaving behind an abandoned channel that slowly fills with sediment from later floods. Floods can preserve archeological sites along these abandoned channels by quickly burying them. It was obvious that the Littler River floodplain needed to be probed along the planned bridge route to search for buried prehistoric sites that might be associated with these old channels. In 1999, TxDOT archeologists employed a backhoe to probe the nearly two-mile-long project corridor through the valley and look for sites buried by flood deposits. They oversaw the excavation of 28 backhoe trenches. Twelve of these trenches encountered artifacts and other evidence marking three prehistoric sites (see graphic at top of page). Site 41MM339 was found to be 11 feet or more below the modern surface on the edge of an old channel that was itself buried. Though this site appeared to be important, it was deep enough to escape damage from bridge construction, and thus no further investigation was needed. However, sites 41MM340 and 41MM341 (now known as the J. B. White site) yielded archeological evidence buried from 1 to 6 feet below the surface of the modern floodplain. Both sites were judged to have important research potential. They produced stone tools and considerable debris from making stone tools, as well as animal bones, mussel shells, and well-defined fireplaces built by Native Americans. Since these sites would be disturbed by the planned bridge construction, they were recommended for further study. Part of the both the initial evaluation and later investigation involved what is known as geoarcheological investigation, the application of geological techniques to address archeological problems. In this case, the archeologists needed to understand how the Little River floodplain had formed over time to determine where the river was when the sites were occupied and how they may have become buried. Specialists with strong geological training carefully studied and sampled the walls of each backhoe trench (and later excavation units). Gradually they unraveled the sequence of flood terrace formation and used radiocabon dating to determine when each period of soil formation and channel cutting had occured. These geoarcheological investigations determined that the archeological remains at the J. B. White site and other nearby sites occur within buried soils formed on a series of floodplain surfaces on which people had lived. These old soils in the vicinity of the sites were cut by several sloughs or old channels of the Little River. The river apparently had moved to near its present position by the time the J. B. White site was occupied. Test ExcavationsFollowing the initial evaluation, the next stage in the research process consisted of digging a series of small test pits by hand at 41MM340 and the J. B. White site, the two sites that would be affected by bridge construction. This testing phase was carried out in 2000 by a team from the Center for Archaeological Research (CAR) at the University of Texas at San Antonio working for TxDOT. Eventually, the CAR archeologists would go on to carry out major excavations at 41MM340, but that’s another story. Their testing of the J. B. White site involved reopening several of the previously dug backhoe trenches followed by the hand excavation of two small areas ("blocks") measuring 2-x-2 meters (about 6-x-6 feet) off of those trenches, as well as 121 auger tests across the site. Two trenches, both in the northern part of the site, had encountered hearths (firepits) and midden deposits (concentrations of prehistoric garbage). The two small testing blocks allowed the CAR archeologists to recognize and define three cultural zones and five hearth features. The three cultural zones reflected the sequence of occupations at the site. For instance, Zone 1 extending from the surface to 40 centimeters (1.3 feet) deep encompassed the remains of an apparent prehistoric garbage pit and a small concentration of chipped stone artifacts. Charcoal from that pit produced a radiocarbon date with a range of A.D. 1407–1440. In addition, 11 sherds from pottery vessels came 30 centimeters (1 foot) below the surface. These discoveries suggested that the archeological evidence in Zone 1 may have been left behind by the Toyah culture, people who lived in central Texas from A.D. 1300-1600 just before the arrival of the first Spanish explorers. The Toyah culture is the name archeologists have given to groups of people who lived mainly west of the J. B. White site on the Edwards Plateau during the Late Prehistoric period. But Toyah peoples sometimes ranged into the coastal prairies and often occupied sites eastward beyond the edge of the plateau and out onto the Blackland Prairie. They were buffalo and deer hunters, but they also took a wide range of other game and collected many plant foods. However, as the investigation of the J. B. White site progressed, it was determined that the occupational remains in Zone 1 were so sparse that they could not tell us much about how Toyah peoples used the site. Cultural Zone 2, which is older than Zone 1, started at about 40 centimeters below the surface and extended to 70 centimeters (1.3-2.3 feet). Mussel shells and many chipped stone artifacts marked this zone along with cooking pit features, including two large baking pits. Radiocarbon dates on charcoal from the bottom of the mussel shell concentration and one of the baking pits show that the zone formed in two occupational episodes dating to about A.D. 685–780 and A.D. 1020–1160. The people who left the artifacts recovered from Zone 2 remain unnamed. But they lived during the period in central Texas (A.D. 700-1300) when Native American groups, depending on a broad-based hunting and gathering lifestyle, adopted the bow and arrow. The shift from the atlatl and dart to the bow and arrow was a change in weapon technology that occurred across all of North America. Locally, the change is marked by the occurence of small side-notched triangular arrowpoints known as Scallorn points. At the J. B. White site these points are found in association with distinctive types of stone tools known as Gahagan or Friday knives. This period of change also is marked by the introduction of ceramic technology—the making of earthenware pottery vessels. However, though small numbers of potsherds (fragments of ceramic vessels) were found at the site, most were associated with Zone 1 and none could be unquestionably related to the occupation represented in Zone 2. This fact suggests that pottery was not an important part of the cooking technology of the people. Cultural Zone 3, the oldest and deepest zone, was recognized at a depth of 90–110 centimeters (3.0–3.6 feet) in both blocks, but especially in Block 2. The archeologists found artifacts in smaller numbers to a depth of 160 centimeters (5.2 feet). During the testing phase, the age of Zone 3 was not precisely determined, as no radiocarbon dates were obtained. However, Zone 3 was thought to represent occupations dating to the Late Archaic period similar in age to those investigated at nearby site 41MM340. Later excavations determined that Zone 3 does indeed represent occupations dating to A.D. 600 to 800, the waning centuries of the Late Archaic period. Major Excavations: Targeting Zone 2Based on the CAR testing, the Zone 2 occupations at J. B. White were targeted for more intensive research. Testing had shown that the archeological evidence in Zone 2 would allow researchers to address some basic questions about the region's prehistory, some of which have tantalizingly elusive answers. First, were the people who lived at the J. B. White site the same people who frequented the nearby Edwards Plateau to the west before the Toyah folk? If not, did these people make a living in the same way as those early folks before Toyah on the Edwards Plateau? In other words, did these people practice the same kinds of hunting and cooking technologies as their close neighbors to the west, and did they eat the same kinds of animals and plants? Answers to these questions could help explain how the J. B. White site fits into the overall picture of how prehistoric Native Americans used the Little River valley. For instance, did people live there for short stays (a few days) or longer periods (a few months)? How many people lived there, and how often did they return? And did the ways they used the site change over time? (Visit the TBH exhibit, Prehistoric Peoples of the Plateaus and Canyonlands to learn about life on the Edwards Plateau.) A difficult but fascinating question is how people at the J. B. White site interacted with the early farming peoples to the east, the Caddo villagers of east Texas. One hypothesis proposed by archeologist Dr. Harry J. Shafer argues that Caddo peoples lived at sites like J. B. White to take advantage of the rich resources of the Blackland Prairies and Oak Woodlands in order to help support large ceremonial centers in their east Texas homeland. (Visit the Tejas exhibits on TBH to learn all about the Caddo peoples). To answer these kinds of research questions, archeologists needed different kinds of information. They would need large samples of artifacts such as stone tools as well as other campsite debris such as animal bones, mussel shells, burned rocks, burned clay, and charred wood and other plant remains. And they would need information on context and associations: how the artifacts and other materials were distributed across the site in relation to features such as cooking hearths and baking pits. To collect these kinds of data, large-scale excavations had to be done. The excavation phase was carried out by a research team from Prewitt and Associates, Inc., an Austin-based archeological consulting firm under contract with TxDOT. The research team had extensive experience excavating sites of similar age to the east in the Oak Woodlands of Freestone and Leon Counties, and they knew that for such a large excavation they would need a crew of 8 to 10 people for about three months. The crew assembled was a diverse group of professional archeologists who had trained at many different institutions of higher learning. This crew shouldered all the heavy lifting while implementing the science. And the heavy lifting was considerable, since the crew excavated 95 cubic meters (3,354 cubic feet) of dense clay loam, which they shoveled into buckets. Each bucket of the clay-rich soil had to be soaked in a solution of baking soda and water to dissolve the clay so it could be washed through screens from which the small artifacts were recovered. Crew members lifted about 11,400 buckets of this slurry into screens to recover artifacts and other cultural materials. This is the equivalent of lifting the weight of at least 28 Chevrolet Suburbans, bucket by bucket. Real archeological work requires lots of hardwork and keen attention to small details. |

|

||||||