|

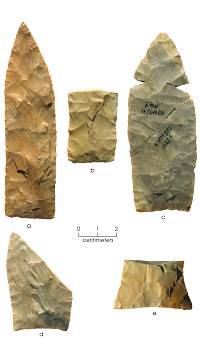

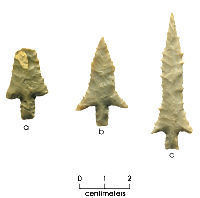

Darl dart points (top row) and Scallorn arrow points (bottom) mark the technological transition in hunting equipment at the J. B. White site from use of the atlatl and dart to the bow and arrow. Scallorn arrow points were made and used throughout the occupations of the site, but Darl dart points were used only in the earliest occupations. Click to see full image. |

|

View of the Loeve-Fox site area, located on the San Gabriel River some 75 miles west of the J. B. White site. Similarities between the two sites, as well as the neighboring Hoxie Bridge site, suggest they were part of the same population local to the region during the Late Prehistoric period. TARL archives.

|

|

The fact that the people who lived at the J. B. White site made and used Alba points suggests that they were in contact with the east Texas Caddo groups who built the burial mound at the Davis site.

|

| |

| |

|

Caddo traders are shown in this artist’s recreation of the Davis site. Strong connections between the J. B. White site and the Davis site are evinced in several of the stone tool types, including Alba arrow points and Gahagan knives. Inset from painting by Nola Davis, courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife. |

| |

|

Friday knives have convex to straight blade edges with a generally straight base. Gahagan knives have recurved edges that flare out near the concave base. These complete knives and base fragments from the J. B. White site show characteristics of both types, with some, like specimen “e,” being somewhere in between. |

| |

One benefit of trade between people of the Little River area and the Caddo may have been the creation of alliances between different groups of people. Such alliances could have helped prevent competition between various groups from getting out of hand, leading to violent conflict. |

| |

| |

|

Photograph of the excavations in Mound C at the George C. Davis site show how Alba points were found within the burials. Alba arrow points in Feature 161 are tightly clustered and with tips pointed all in one direction, as if they had been hafted and in a quiver. Two elaborate stone celts (axe heads) were also recovered nearby. TARL archives.

Click to see full image. |

|

Archeologists often are asked questions about who the prehistoric peoples they study actually were and what happened to them. Such questions can be partially answered by looking at contacts and connections among neighboring groups. This can be done, given the lack of written records, by comparing how people in different areas lived and by comparing the kinds of artifacts they created. With these kinds of comparisons, even a small campsite such as the J. B. White site can help flesh out the story of how the people who lived there interacted with others.

The J. B. White site represents a small slice of a way of life that the people who lived along the Little River and its tributaries followed for at least 700 years, from about A.D. 600 to 1300. These native peoples possessed a hunting tool kit consisting of the bow and arrow and knives, they used large and small pits and surface hearths for cooking, and they relied on a variety of animal and plant foods. Evidence of this lifeway also has been documented at the few other excavated sites in the Little River drainage that are of similar age as the J. B. White site. Two of these are the Hoxie Bridge site and the Loeve-Fox site, both of which are located along the San Gabriel River in Williamson County. The strong similarities between these sites suggest that the people who created them were part of the same population local to this region.

The tools and stone debris they left at the J. B. White and Hoxie Bridge sites, in particular, indicate that crafting stone hunting tools was important to the people who lived there, and that they were especially masterful at making arrow points and knife blades. The styles of these hunting tools changed through time, and these changes provide evidence of the strong connections these people had to central Texas as well as clues about contacts they had with people who lived outside the central Texas region.

The deepest and thus earliest levels of the excavations at the J. B. White site dating to about A.D. 650 produced several Darl dart points along with Scallorn arrow points. These likely mark the transition from use of the atlatl and dart for hunting to the bow and arrow. Darl points were common to the eastern margin of the Edwards Plateau and indicate long-held connections between groups on the Blackland Prairie and those to the west. The work of Clell Bond at the Hoxie Bridge site and Elton Prewitt at Loeve-Fox showed that Darl dart points eventually were replaced by Scallorn arrow points. Scallorn arrow points were made and used throughout the occupations at the J. B. White site, but they were used most frequently between A.D. 900 and 1100. After that, until about A.D. 1300, Alba arrow points were made and used most frequently, and by the end of the site’s occupation Alba points and a few Perdiz-like points were the predominant arrow point styles.

Alba points are also well represented at the Hoxie Bridge site but not so at Loeve-Fox. Alba points are found often at sites in east Texas and are most-famously associated with the George C. Davis site in Cherokee County, where Dee Ann Story of the University of Texas at Austin and her crew discovered them en masse as burial offerings. The fact that the people who lived at the J. B. White site made and used Alba points suggests that they were in contact with the east Texas Caddo groups who built the burial mound at the Davis site.

What strengthens this tie is the fact that the Perdiz arrow points from the J. B. White site are not like other Perdiz points from central Texas, which have long stems and deep barbs. Rather, they are more similar to ones that are often found along the western margins of east Texas and that are well made with shorter stems and barbs. Archeologists have found such short-stemmed Perdiz points at the McGuire’s Garden site located in Freestone County, Texas. This site, investigated by Prewitt and Associates for the Jewett Mine, was likely a Caddo hamlet dating to about A.D. 1300, or right at the end of the time the J. B. White site was occupied. Some researchers such as Harry Shafer consider these short-stemmed Perdiz to be the east Texas type Bonham arrow points. The presence of these eastern Perdiz or Bonham points along with the Alba points at the J. B. White site indicates strong eastern connections.

The chipped stone knives recovered from the J. B. White site also tell us something about connections between peoples. Several knife types have been defined by archeologists based on blade and base shape. The types found at the J. B. White and Hoxie Bridge sites include the Friday knife and the Gahagan knife. The Friday knife is found mostly in central Texas. It has convex to straight blade edges and a generally straight base. The Gahagan knife, with recurved blade edges that flare near a concave base, is known best from east Texas Caddo mound sites, though it is also found on central Texas habitation sites. Actually, both knife forms appear to have been made and used at the same time, and both occur at the same sites, such as J. B. White.

The classic Gahagan knife was first identified in the early 1900s by Clarence Bloomfield Moore during his excavation of the Gahagan mound site located along the Red River in western Louisiana. The knife type was given the name of the site where it was first identified. However, Gahagan knives both at the George C. Davis site and the the Gahagan site appear to have been fashioned from central Texas chert. This fact, along with the appearance of similar-shaped knives on habitation sites in central Texas, suggests that Gahagan knives were made by central Texas groups who traded them to the east Texas Caddo. Caddo Indians living at sites such as George C. Davis in turn may have traded the finely crafted knife blades to their relatives in what is now Louisiana.

The importance of Alba arrow points and Gahagan knives to Caddo peoples is underscored by their occurrence as burial offerings. During her 1968–1970 excavations at the Davis site, Story discovered clusters of Alba points, as if in quivers, within two burials of important people in Mound C. Another cluster of Alba points, as if in a basket, along with several Gahagan knives was found with offerings set with a burial at the very base of the mound. These Alba points, made of chert from central Texas, varied in shape enough to suggest that they represent collections of arrows from multiple makers. In fact, several of them are very close in style and workmanship to the Alba points recovered from the J. B. White site. This does not mean that the Alba points at the Davis site had to have been made at the J. B. White site, although they might have been, but they almost certainly were made by people who lived somewhere in the Little River drainage. If these people did not actually visit J. B. White on occasion, they knew people who did.

Alba points and Gahagan knives were not just traded away, though. The people who lived at the J. B. White site also made these tools for their own use, as demonstrated by the many points and knives broken in use and discarded there. That people used these particular tools both for hunting and as an asset for trade suggests that the “style” of points and knives was more than just a matter of simple function. In this case, it looks like the styles of the tools the Little River Indians made were dictated at least partly by what the Caddo Indians wanted.

What did the people who lived at the J. B. White site get in return for their well-made arrows and knives? This question is difficult to answer because many kinds of things that could have been traded, such as salt or bear fat, are perishable and leave no physical traces. But one benefit of trade between people of the Little River area and the Caddo may have been the creation of alliances between different groups of people. Such alliances could have helped prevent conflict between these groups, or between them and their other neighbors, from getting out of hand. One reason archeologists think there was conflict during this time period in this part of Texas is that evidence of violent death sometimes shows up. For example, Prewitt discovered a small cemetery at the Loeve-Fox site in Williamson County, and of the 12 people buried there, several had arrow points imbedded in their backs. Violent deaths like these indicate that conflict and aggression were present within the region that included the J. B. White site.

Such alliances may even be reflected in the arrow points found with the burials of important people at the George C. Davis site. The arrows at the Davis site appear to be from many different makers collected into single quivers. These quivers may symbolize the power of alliances to quell conflicts between different groups of people. These alliances could have been what eventually enabled large congregations of people to come together from east and central Texas for trade fairs and other activities. This type of interaction is known to have occurred in historic times when eastern groups such as the Hasinai Caddo came west to the Balcones Escarpment to trade and hunt bison, and there is no reason to think it did not happen several hundred years earlier when Native Americans lived at J. B. White as well.

So who where the people who lived at the J. B. White site and what happened to them? It looks like they were local folk who had roamed the Little River drainage from the Brazos River west to the margin of the Edwards Plateau for many, many years. In fact, their ancestors may have done this for thousands of years. They used the same kinds of tools and exploited the same kinds of resources in the same ways as their central Texas neighbors, but they also had ties with east Texas Caddo groups who built the George C. Davis site mounds. These ties were likely cemented by the trade in certain kinds of arrow points and knives, and the willingness of the people along the Little River to satisfy the desires of their trading partners. With a little luck, those interactions with folks far afield helped the people living on the Little River maintain their territory and smooth any difficulties they encountered with their neighbors.

We do not know what happened to these people. They stopped using the J. B. White site hundreds of years before European explorers, missionaries, and traders came to this part of the New World. Maybe their descendants were among the Indians the first Europeans met, or maybe they had already moved out of the area by then to make room for other Native American groups. Some archeologists think the latter may have been the case, but that is not part of the story the J. B. White site has to tell.

|

|

|

The styles of these hunting tools changed through time, and these changes provide evidence of the strong connections these people had to central Texas as well as clues about contacts they had with people who lived outside the central Texas region.

|

| |

|

Alba arrow points from the J. B. White site. These points are quite similar in form and quality of workmanship to some of the Alba points from the George C. Davis site in Cherokee County, Texas. (See photo below for comparison.) |

| |

|

Alba arrow points recovered from burials at the George C. Davis site bear striking similarities to those from the J. B. White site (shown above). |

| |

|

Perdiz arrow points from the J. B. White site are similar to short-stemmed Perdiz points recovered from some east Texas sites such as McGuire’s Garden. Click to see full image and identifications. |

| |

|

Artist's depiction of an elaborate Caddo burial, based on one documented by archeologists beneath Mound C at the George C. Davis site. Various grave offerings, including caches of Alba points and Gahagan knives, were buried with the individuals in the mound. Painting by Nola Davis, courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. |

| |

|

Thirty-five Gahagan knives, such as those shown above, were recovered from human burials in Mound C at the George C. Davis site. Dr. Harry J. Shafer, who originally analyzed these specimens, found that the high-quality chert from which they were made was not local to east Texas. The chert was light gray, tan, brown, and tannish brown. Shafer also pointed out that the large sizes of the knives indicated that they had been made from large river cobbles or chert slabs from bedrock sources, and that the makers of the knives probably lived close to the chert sources. These kinds of chert can be found in gravel bars in the Little River near the J. B. White site, and there is no doubt that the knappers who lived there had the skills to make the tools that archeologists call Gahagans. Photograph courtesy of Harry J. Shafer. |

| |

|

Alba points, jumbled together as if in a bag or basket, and two Gahagan knives were recovered from the same concentration in Feature 134 discovered at the base of Mound C at the George C. Davis site. TARL archives. |

|