|

||||||||||||

|

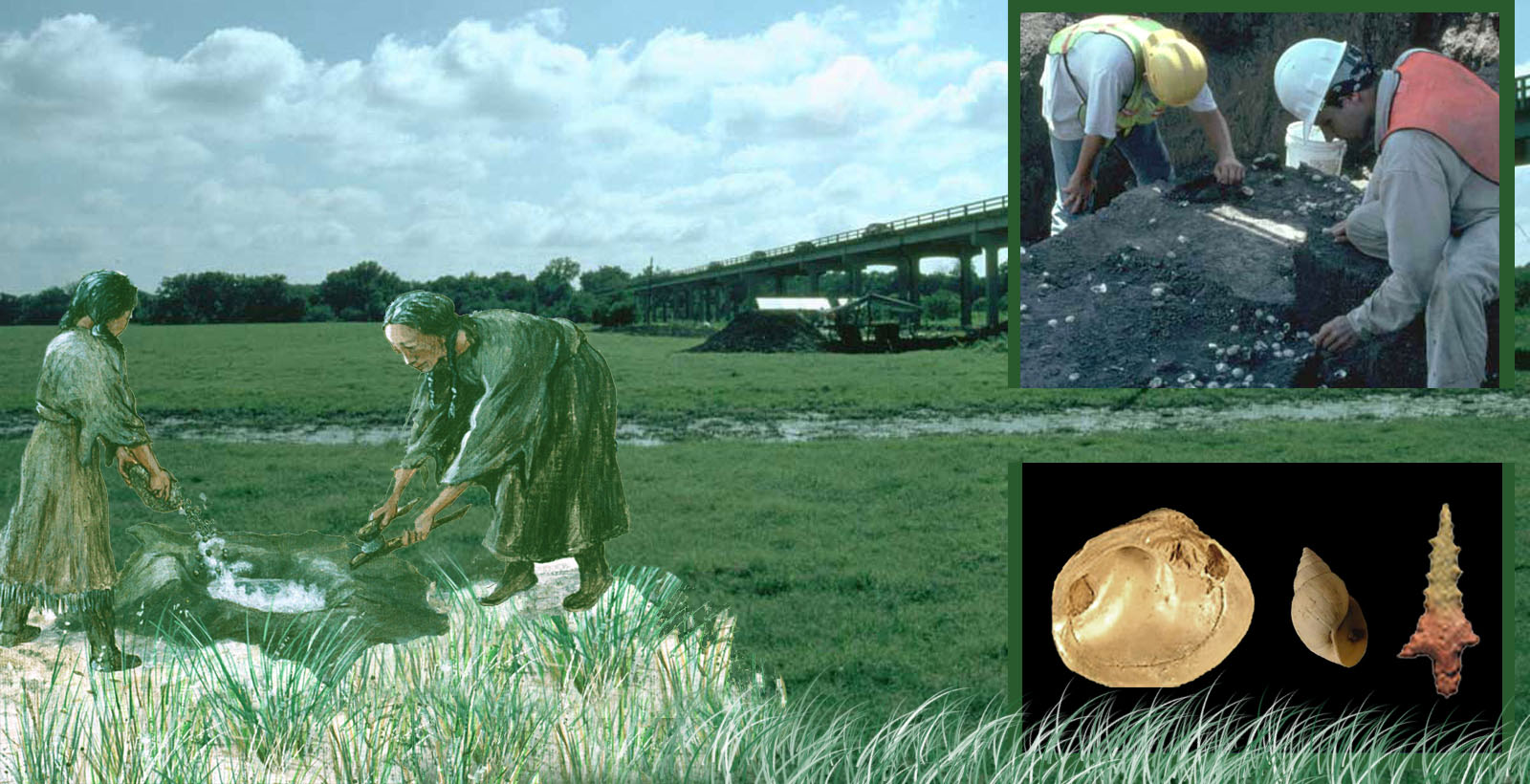

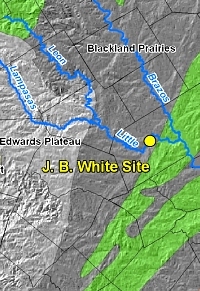

This is the story of finding, excavating, and understanding one small prehistoric campsite located on the floodplain of the Little River in Milam County, Texas. This camp is one of many places in the area where native peoples (Native American Indians) lived about 700 to 1,400 years ago. Their many other camps and villages were scattered within the valleys of the Little River and its tributaries. The territories of local groups probably extended eastward to the Brazos River and westward to the Balcones Escarpment, the edge of the Edwards Plateau. The site is named for avocational archeologist and collector J. B. White, who likely crossed over his namesake site on one of his many excursions through the fields and stream valleys of the county during the 1930s. In an article he wrote for the Central Texas Archeologist he extolls the archeological richness of the Little River area:

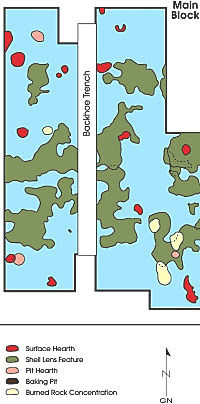

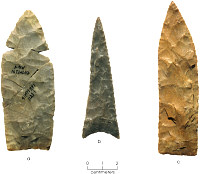

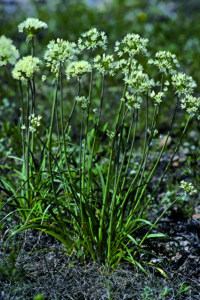

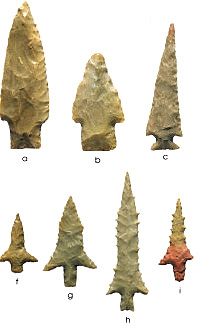

Although there have been few large-scale archeological investigations in the Milam County area, there is good reason to put stock in White’s somewhat hyperbolic prose. The local area is rich in natural resources and these would have served as powerful attractants to hunting and gathering peoples. In this region, the Little River flows eastward from the Escarpment across the Blackland Prairies and into the Oak Woodlands. These two different ecological zones and the floodplain forest adjacent to the river provided a wealth of resources from which prehistoric groups could make a living. These resources included easy access to water, a great variety of animals and plants for food, wood for fuel, and flint or chert for tools. The site’s location along the Little River was advantageous for the people who lived there, since the river provided an east-west link to other Indian peoples in adjacent regions. The information recovered from the J. B. White site provides a glimpse of how these groups organized themselves across this landscape to take advantage of natural resources, as well as how they interacted with groups from neighboring regions. The SiteThe J. B. White site (official designation: 41MM341) was a camp where a few related families lived, probably during the summer months when the possibility of flooding of the Little River was low and when access to the many resources of the floodplain was unlimited. These people hunted deer and other animals such as raccoons, opossums, and rabbits, all of which would have been plentiful in the area. At the same time, they collected a wide range of other foods, including turtles and mussels from the river as well as some fish and ducks. Also, they gathered up wild onions and land snails and brought them to the camp from nearby open grassy areas of the prairie. The floodplain forest and oak woodlands provided nuts and fruits such as pecans, hickories, and plums along with oak wood, which they selected especially for fueling their campfires. Another thing these Indians did was make hunting tools using high-quality chert ("flint") gathered from the Little River gravel bars. Most of this chert came from the Edwards Plateau, where it crops out along the Balcones Escarpment and was carried eastward by the river. The tool makers, known as knappers, brought chert cobbles back to the camp and broke them in systematic ways to fashion mostly arrow points and knife blades. Concentrations of stone flakes and chunks along with tools that broke while they were being made mark at least 10 tool-making episodes that took place at the camp. Other stone tools recovered from the camp in smaller numbers, such as adzes, gouges, and choppers, may have been used for working wood and suggest that such perishable tools as wooden arrow shafts and knife handles also were made on the site. Most cooking and tool making took place around small hearths built directly on the ground surface. The camp was a workshop as well as a place of habitation, and it was used in this way on and off over a period of 700 years based on radiocarbon dates ranging from A.D. 600 to 1300. Flooding of the Little River occasionally deposited sediment on the campsite, covering and preserving the remains of each occupation. The camp was used more often between about A.D. 1100 and 1300 than it was before this. Activity areas that overlap each other mark this increased use, as does the use of large cooking or baking pits. A cluster of 10 large cooking pits ranging from 4 to 6 feet across was found about 30 feet south of the main activity areas at the camp. These pits were probably clustered away from the main part of the camp because of the heat and smoke they generated. The J. B. White site was first occupied during the period when hunters were shifting from using darts and spear throwers (atlatls) to the newer bow and arrow weapon system. This can be seen from the fact that the stone points made and used at the site include Darl dart points and Scallorn arrow points marking the earliest occupations of the site, and Scallorn, Alba, and Perdiz arrow points used later during most of the site’s history. Large stone knife blades, called Gahagan knives, were also part of the hunting tool kit used by the site’s inhabitants. These knife blades were consistently found with all three types of arrows recovered. The kinds of arrow points (true "arrowheads") recovered as well as the kinds of activities and camp features discovered suggest the people who lived at the J. B. White site were influenced in various ways by their neighbors. The large number of Alba arrow points, a style commonly used by east Texas Caddo groups, in the later occupations of the site suggests increased contacts in an easterly direction. Whether these contacts involved simple trade, marriage, actual movement of whole groups of people, political alliances, or some combination of these is difficult to determine. There is evidence to suggest that some arrows and knives made at the J. B. White site were carried away from the site. It is possible that tools fashioned from the sought-after chert available in the Little River nearby may have been made as trade items. The Gahagan knife, in particular, is a form that shows up as part of hunting tool kits in many central Texas sites and also as offerings in elite Caddo graves at the George C. Davis site in Cherokee County, Texas. In This Exhibit The J. B. White site exhibit provides significant new information for Texas Beyond History viewers and the archeological community. First, it helps fill a critical geographical gap. There has been scant archeological research conducted in east-central Texas. This exhibit summarizes some of the scientific data which raise important questions about patterns of prehistoric life in the region. Second, readers will learn much about the “hows and whys” of archeological research, from data recovery using state-of-the-art excavation techniques to how the results are interpreted. In the process, we will gain a clearer picture of the life of Indian peoples along the Little River during the Late Prehistoric era. In Investigations, the story of how and why the J. B. White site was found, tested, and excavated unfolds. Two sections Tool-Making Workshop and Daily Life, detail how the evidence was analyzed and interpreted, including tracing patterns of artifacts and features, to illuminate how prehistoric peoples used the site. In Contacts and Connections we speculate that the Little River folk may have participated in regional trade networks with other prehistoric peoples, in particular the Caddo of east Texas. Scratching the Surface points out the need for additional scientific investigations in the Milam County area to flesh out a more complete picture of native life. Mussel Mania is a special section for schoolchildren featuring Dr. Dirt, the Armadillo Archeologist, and Dr. Molly, the Malacologist, in an interactive learning activity about the significance of mussels (freshwater clams), both in prehistoric as well as modern times. Credits & Sources explains that the J. B. White exhibit was created in collaboration with Prewitt and Associates, Inc., the Austin-based archeological consulting firm that conducted excavations and analysis of the site on behalf of the Texas Department of Transportation. |

|

||||||||||