Conclusions: Significance of the McKinney Roughs Site

Prominent excavated sites in the region with Darl-period evidence. |

|

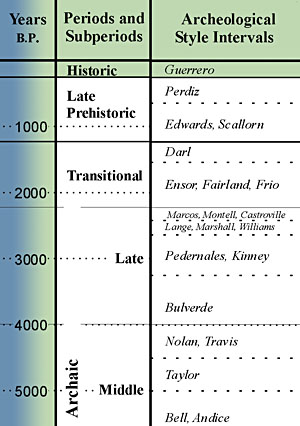

Discovered during archeological survey prior to the construction of a resort hotel complex, the McKinney Roughs site has proved to be an important, stratified Transitional Archaic site. Prehistoric living surfaces were preserved almost as they were left by campers one to two thousand years ago, providing a "snapshot" of prehistoric lifeways along the Colorado River. Although most organic materials such as food, bone, and wood decayed long ago, a substantial amount of materials were preserved to reveal a living surface. The excavations uncovered materials ordered in discernible patterns that reveal the behavior and activities of those who left them, the type of evidence which anthropologist Lewis Binford has termed a "fossilized society." Rarely found in archeological sites, such intact, undisturbed surfaces allow archeologist to apply comparative ethnographic models derived from observation of modern hunter-gatherer sites. At McKinney Roughs, Binford's model of "drop-toss zones" in modern camps was used to help interpret the spatial patterning of the campsite. With this type of interpretation, researchers can almost visualize the camp layout and activities which took place, in this case, cooking, and processing of mussel shells as well as toolmaking. Occupation of the McKinney Roughs site occurred during a period of widespread change in the region. During this time, climatic conditions became more mesic (wetter), following centuries of dryness. Several researchers believe that burgeoning populations and increased interaction among groups toward the end of the Archaic were an important catalyst for cultural change. At other sites in the area, these changes are recorded through innovations in technology—the emergence of the bow and arrow weapons system—as well as other behavioral patterns. At McKinney Roughs, the people hunted with projectiles tipped with small, chipped-stone points called Darl. This point type serves as a key index, or time marker, and may have been one of several transitional styles ancestral to the first Late Prehistoric arrow points. Other small points of the Transitional Archaic time period include types Ensor, Frio, and Fairland, but the Darl type appears to be the latest, perhaps overlapping in time with Scallorn and other early arrow points. Some archeologists are uncertain, in fact, whether Darl is a dart point or arrow point. Archeologist LeRoy Johnson has speculated that the Darl point may actually represent the first arrow point to appear locally. Lacking wooden shafts and other components of the weaponry system, such as bows or atlatls (dart throwers), which were not preserved, it is difficult to establish how the projectile was fired. Darl points are common throughout large portions of central Texas. This suggests the Darl folk operated over wide-ranging territories, moving seasonally through several ecological areas, and possibly trading their projectile points and perhaps other materials with peoples in neighboring areas. In Central Texas cultural chronologies, the transition from the Late Archaic to Late Prehistoric has been rather ambiguous and the subject of much recent debate. In part the ambiguity derives from the lack of well-preserved, stratified sites of this age. Almost all of the excavated sites with significant Darl components, including Hoxie Bridge and Wunderlich (at Canyon Reservoir) have poor integrity and are intermixed with materials from other time periods. The same is true of other excavated sites on the Edwards Plateau or near the Balcones Escarpment, including the Mustang Branch, Williams and Collins sites. In contrast, the recently excavated J. B. White site in Milam county, some 75 miles north of McKinney Roughs, provides a view of an intact encampment in a similar setting, characterized at the deepest levels, dating to about 650 A.D., by Darl dart points as well as Scallorn arrow points. These likely represent the transition from use of the atlatl and dart to the bow and arrow. A later overlying component with numerous Scallorn points is better preserved and has remarkable delineation of activity areas similar to those at McKinney Roughs, including areas for processing large quantities of mussel shell and land snails. These patterns suggest that in spite of other changes afoot, subsistence practices remained relatively unchanged from the Transitional Archaic to the Late Prehistoric. Although the campers at J.B. White sought the diverse resources at the Little River site, there was also evidence of cultural connections both to the east and west at this site. They procured fine-quality, Edwards Plateau cherts for their tools, some of which were traded out of the region. Prewitt and Associates archeologist Eloise Gaddis, who oversaw J. B. White site excavations, noted: It is likely that the nomadic hunter-gatherers who lived at the J. B. White site in the summer months lived at sites like Hoxie Bridge during other times of the year. But these people also had more-distant connections to east Texas.... The transition from Archaic to Late Prehistoric lifeways was a change in technology, ideology, broad new interaction spheres, and shifting cultural identities. The McKinney Roughs site has allowed archeologists to better understand prehistoric human adaptation during this transitional time period by examining discrete slices of time represented by the cultural components preserved in the site. McKinney Roughs provides one of the few clear pictures of a Transitional Archaic campsite presently known, contributing to a better understanding of one of the major changes in regional prehistory. |

|