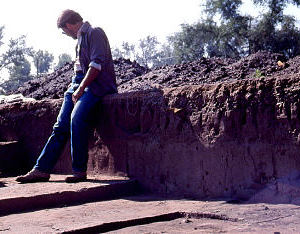

Excavations at the Ysleta Jacal Site

Ysleta plaza and the Jacal site. Archeological excavations conducted there prior to construction of the Ysleta Neighborhood Health Clinic revealed a small jacal community dating to shortly after the Pueblo Revolt period. As denoted in the marker, the site was "part of the earliest Native American settlement associated with a Spanish Mission in the state of Texas." |

|

|

|

None of the primary corner or roof support posts were present and no burned beams were found among the mounds of wood and daub. This indicates that the house was probably intentionally razed and the valuable wood beams were removed for use elsewhere. The absence of domestic items and tools on the floor of the house also indicates that it had been abandoned prior to its demolition and burning. Some years later the eastern edge of the house was removed by construction of a narrow historic irrigation ditch or perhaps a trench for a modern utility line. Pits of various sizes and shapes were the most common type of archeological feature. Several of the larger and more irregular pits probably served as borrow pits for gathering mud clay for use in both house construction and pottery manufacture. Pits with bell-shaped profiles may have served as temporary underground storage facilities. Whatever the original use, almost all the pits finally served as locations for the disposal of animal bone and other food remains, broken pottery vessels, and other household trash. Most of the food remains were recovered from within these pits, and included corn cobs and kernels and charred peach pits, showing that the native groups had access to this Spanish-introduced fruit. Several wild plant foods such as mesquite, amaranth, and prickly pear cactus were also found, showing that the inhabitants continued to gather and consume wild plant foods in a manner similar to prehistoric groups in the area. Large quantities of animal bone were recovered. Bone deposits were particularly dense in the disposal pits scattered across the site. Analysis of the bones identified numerous species including both domesticated animals introduced by the Spanish and non-domesticated animals common to the surrounding desert and mountains. Compared to the high proportions of domesticated cow, pig, chicken, and goats or sheep found at later mission-era settlements in the valley, the Pueblo Revolt occupation at 41EP2840 had much higher quantities of non-domesticated animals such as rabbits, fish, birds, and deer. Additional evidence that Native groups continued to hunt game is demonstrated by the presence of arrow points and stone tools. Thousands of plain brownware pottery sherds were recovered from refuse pits and from the deposits around the jacal house. The ceramic tradition represents a blend of Spanish-influenced vessel forms and indigenous brownware manufacturing techniques. Very little of the pottery was decorated with red slips or white slips. Large ollas and serving bowls were common vessel forms, but Spanish forms such as plates and candlesticks were also manufactured. Some of the ceramics may have been brought along from the northern pueblos, and include various red and red-slipped wares, Rio Grande Glazewares, and Tewa Polychrome. Mexican majolica wares such as Puebla Blue-on-white, Puebla Polychrome, and Abo Polychrome were also present, but in relatively small numbers. |

|

Ceramics recovered from the Ysleta Jacal. The site’s ceramic tradition represents a blend of Spanish-influenced vessel forms and indigenous brownware manufacturing techniques. Left: Valle Bajo brownware sherds produced locally; middle: Tewa polychrome bowl sherd (on left) and Ogapage polychrome jar sherds (on right) from the New Mexico pueblos; right: collection of Puebla polychrome (blue and black on white), Abo polychrome (Green, yellow, blue, and black on white), and Pueblo Blue-on-white majolica sherds from Mexico. Photo courtesy of Batcho and Kauffman Associates. |

The absence of painted ceramics and any noticeable quantity of majolica and other quality ceramic vessels may reflect the lack of social and economic status of the household. Very few items suggestive of status or social differentiation were found. Only three glass beads were recovered from the site. Very little metal was present, although this may have resulted from lack of access due to disruption of supply routes along the Camino Real during the Pueblo Revolt period. Analysis of animal bones and butchering marks indicate and that most meat was prepared and consumed within the household and that lower-quality portions were consumed. Yet, despite the apparent low social and economic status of the household social group residing at the Ysleta jacal site, there is tantalizing evidence of an undercurrent of resistance to total Spanish authority in the form of Native American social and religious practices. The lack of evidence for social status among the residents of the Ysleta jacal structure should not be construed to mean that there was no social or leadership status among the Tigua and Piro groups living under Spanish rule. Religious practitioners and lineage or community leaders would undoubtedly have been present as observed among all ethnographically and ethnohistorically documented Southwestern pueblo societies. Several items of shell, pigments, and mica or selenite were recovered at the site. These types of items are strikingly similar to those found at prehistoric pueblos across New Mexico (see Madera Quemada) and west Texas. More telling was the recovery of a ceramic animal figurine and a projectile point coated in red ochre pigment. When considered as a whole, the presence of this collection of items demonstrates the continuation of social and religious practices having considerable time depth in the region. |

|