|

The history of the El Paso missions and settlements is one of amalgamation of European and native cultures and, with few exceptions, the loss of identities of once-distinct native groups. Before the arrival of the Spanish, El Paso had been inhabited for thousands of years by hunting and gathering peoples. Around A.D. 400, native peoples of the area began living in pithouse villages and experimenting with crops. Through time they built larger and more complex villages and by A.D. 1200, they were living in pueblos, relying heavily on crops for food, and participating in trade with peoples across the American Southwest and northern Mexico. Around A.D. 1450, the pueblos of El Paso were abandoned and the people who remained in the region reverted to the mobile hunting and gathering lifestyle of their ancestors.

In their early expeditions to the El Paso area, the Spanish explorers encountered two groups of Native Americans whom they referred to as the Mansos and the Sumas. The Mansos occupied the Rio Grande in the immediate area of El Paso, north to Las Cruces. The Sumas were found along the Rio Grande southeast of El Paso, as well as in portions of northern Chihuahua, Mexico. Both groups lived in small communities, or rancherías, of primitive structures consisting of straw, brush, or poles. They may have also slept outside on beds of grass while in more temporary camps. Neither practiced horticulture, but subsisted primarily on rabbits, rats, fish, mesquite beans, mescal, prickly pear, agave, yucca, and various roots and seeds. Both groups wore body paint and little clothing, and carried bows, arrows, and clubs. The Spanish described the Sumas as participating in ceremonies or communal gatherings involving intoxication. Whether this involved some form of fermented beverage or hallucinogen, such as peyote, is unclear.

The first recorded Spanish expedition, or entrada, to pass through El Paso was the Rodríguez/Chamuscado entrada of 1581. Hernán Gallegos, chronicler of the expedition, described the area south of present-day El Paso as suitable for ranches and cultivation, but reported no people living there. Two years later, Antonio de Espejo and his expedition camped in an area south of El Paso which he described as having very good land and climate, with buffalo herds nearby, abundant game and birds, mineral deposits, many forests and pasture lands, rich natural deposits of salt, and abundant water in large marshes and pools. Here they encountered Sumas who brought the explorers such large quantities of mesquite, corn, and fish that they feasted for three days, and much of it still went to waste.

These people, who must have numbered more than a thousand men and women, and who are settled in their rancherías and grass huts, came out to receive us…. Each one brought us his present of mesquital, which is made of a fruit like the carob bean, fish of many kinds, which are very plentiful in those lagoons, and other kinds of their food, in such quantity that the greater part spoiled because the amount they gave us was so great.

–Antonio de Espejo, 1583

The Entry of Don Juan de Oñate

The most important entrada to pass through El Paso was the Oñate entrada. In 1595, King Phillip II of Spain appointed Don Juan de Oñate as governor, captain general, caudillo, discoverer, and pacifier of New Mexico, a territory that had not yet been conquered. The purpose of the entrada was both to find riches for Spain and to convert the native population to Christianity. Oñate was commanded to "attract" the native people he encountered to the Catholic faith with peace, friendship, and good treatment.

The promise of titles, riches, and adventure coaxed many Spaniards like Oñate to financially support their own expeditions. The son of a wealthy silver mine developer, Oñate arranged to lead 400 soldiers, 130 families, 1000 head of cattle, 1000 head of sheep, and 150 mares on a trek across the dune seas of the Chihuahuan desert. In late January 1598, Onate and his party departed from Santa Barbara in southern Chihuahua, Mexico. While previous Spanish expeditions to the Trans-Pecos region (of what is now Texas) and New Mexico had followed an established northbound course along the Río Conchos, Oñate chose his route as a shortcut. Crossing the desert resulted in many hardships as the company struggled for survival. They traveled for four days without shelter or fresh water in hopeless search of "el paso por las moñtanas"-a pass through the mountains-that would allow them to continue west. To their relief they came upon the Rio Grande and followed it upstream to present-day San Elizario, Texas.

On this site on April 30 1598, Oñate held a ceremony to formally take possession of all the land surrounding the Rio Grande in the name of King Phillip II of Spain. Oñate gave a sermon thanking God for delivering them safely across the harsh desert. His speech was witnessed and a written copy notarized by Juan Perez de Donis, royal notary and secretary of the jurisdiction and expedition, so that it could become a legal claim to the land for the King in the eyes of Spain. The ceremony, an event also known as "La Toma," marked the beginning of over 200 years of Spanish rule in Texas. The celebration was concluded with a play written by Captain Marcos Farfán de los Gados. Although copies of the play have not survived, it is likely the first theatrical piece written in what is now the United States.

On May 1, 1598, the entrada continued traveling up the Rio Grande and within three days met their first native people. They were armed with bow and arrow, but offered as their first words "manxo, manxo, micos, micos," which meant "peaceful ones" and "friends." From these words, the Spanish derived the name, Mansos. The Indians also made the Sign of the Cross, considered by some to be evidence that the expeditions of Francisco Vasquez Coronado or Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca had passed through El Paso. The Mansos led the company to a ford on the river that they commonly used and helped them to cross it. The entrada then continued up the river until it reached present-day El Paso. Here, the river flowed through a break in the mountains. Termed "El Paso del Río del Norte—the pass of the north—it would serve as the Spanish gateway to the West.

Soon after leaving the pass, the entrada encountered a Manso village. Oñate and his men presented the Mansos with clothing and the Mansos repaid them with fish freshly caught from the river. In an act of thanksgiving, Oñate arranged for a feast to be held in honor of the company's miraculous survival and asked the Mansos to be their guests. The banquet included fish, duck, and geese as well as supplies from the entrada's stores. Though not a harvest celebration, this act of thanksgiving was the first to be celebrated in what is now the United States.

The entrada continued well into present-day New Mexico where Oñate established the first European settlements in the region. He sent out scouting parties in all directions to search for gold and silver, but they returned empty-handed. With no gold, silver, or other significant resources to be gained, the company fell into disarray. Oñate's soldiers began to demand tribute from the Pueblo people of New Mexico. When the people of the Acoma pueblo refused and rose up against the Spanish, Oñate cruelly punished them by killing 800 people, enslaving 500, and cutting the left foot off of all men over the age of 25. Formal charges were brought against Oñate for mismanagement which claimed that he had become oblivious to the needs of the colonists and falsified information about the entrada's findings in reports to the King. In 1607 Oñate resigned command of New Mexico and returned to Spain to face charges.

Don Juan de Oñate is a controversial historical figure. To the Spanish, he was the "pacifier of the west," credited with establishing Spain's legal claim to New Spain, opening a portal to the west, and colonizing New Mexico. To the native people of New Mexico, however, he was a cruel tyrant who invaded their lands.

Establishment of Missions

After the founding of Santa Fe in 1609, El Paso became a critical point in the long north-south route of communication and trade (soon to be known as the Camino Real) between the Mexican interior and the missions and Spanish settlements of the province of New Mexico. The Franciscan Father Custodian Alonso de Benavides spent much time in the El Paso area during the early part of the 17th century, and recommended that a mission and presidio be built among the Mansos to convert and settle them, as well as guard the highway to New Mexico and develop mines and farms in the area.

Between 1656 and 1659, the conversion of the Mansos of El Paso and the nearby Sumas and Janos began in earnest. Fray García de San Francisco, Fray Francisco de Salazar, and a group of Christian Piros from New Mexico began the aggregation of most of the Manso rancherías into settled habitations. In 1659, they established Mission Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe del Rio del Norte de los Mansos on the south side of the Rio Grande in present-day Ciudad Juárez for the Mansos. In 1665, Fray García and Fray Benito de la Natividad established the missions of San Francisco de la Toma for the Sumas and La Soledad for the Janos. Guadalupe de los Mansos was situated at a strategic location at the pass of the Rio Grande and became the mother church for El Paso. Over the next several years, the crude structures of the early complex were replaced with more permanent buildings. At a dedication ceremony of its church in 1668, 400 Mansos were present. In addition to the local Mansos, the mission served Piros, Sumas, Tanos, Tiguas, Tompiros, Apaches, and Jumanos who had been forced to flee their homelands by famine, disease, and warfare. By 1680, the mission ministered to over 2,000 native people.

Exodus from the North

A violent upheaval among the native peoples of the upper Rio Grande missions in New Mexico brought drastic change to the missions of El Paso. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 left more than 400 Spanish colonists, 21 Franciscan missionaries, and 346 native people dead in New Mexico. Santa Fe was abandoned and more than 2,000 Spanish refugees and 317 Piros, Tiguas, Tompiros, Tanos, and Jemez retreated to El Paso. It is not clear whether these native people were loyal to the Spanish or were their slaves and hostages. The native people settled at Guadalupe de los Mansos while the Spanish settled in camps at San Pedro de Alcántara, Real del Santisimo Sacramento, and San Lorenzo de la Toma. Governor Antonio de Otermín made an attempt to reconquer New Mexico in the winter of 1681-1682, but was unsuccessful. On his trip back to El Paso, Otermín stopped at Isleta and burned the Tigua Pueblo there, taking its 385 residents hostage. Only 305 survived the trip to El Paso.

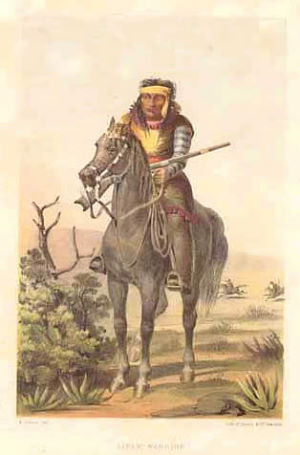

The Spanish now realized that the reconquest of New Mexico was not going to happen quickly and made arrangements for an indefinite stay, establishing El Paso as the temporary capital of New Mexico. Because they were considered temporary settlers, the New Mexicans were permitted to plant their crops wherever they considered it most convenient. They soon began to encroach on lands that belonged to the Mansos, Sumas, and Janos, making for uneasy neighbors. The large number of captive Tiguas now in El Paso further increased tensions between the native people and Spanish. The situation worsened when Apache raiders began to shift their activities south, from the recently abandoned New Mexico missions to El Paso.

In 1682, Otermín attempted to stabilize the situation by founding the missions of Corpus Christi de la Ysleta (Ysleta del Sur) for the Tiguas, San Antonio de Senecú for the Piros and Tompiros, and Nuestra Señora de la Limpia Conceptión del Socorro for the Piros, Tanos, and Jemez. These missions, particularly Socorro, strongly resembled the missions of New Mexico in their construction materials and use of native decorative elements.

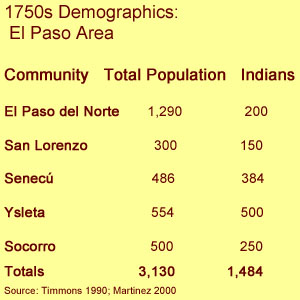

In 1683, newly elected Governor Jironza Petríz de Cruzate established the Presidio de Nuestra Señora del Pilar y Glorioso San José at San Pedro de Alcántara and, with Fray Nicolas López, reorganized the Spanish and native settlements, establishing two new missions for the Sumas called Santa Gertrudis del Ojito de Samalayuca and Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de los Sumas. The Spanish now lived at San Lorenzo, Ysleta, San Pedro, and Señor San José, a new settlement at the presidio. The Piros resided at Socorro and Senecú, the Tompiros at Senecú, the Sumas at San Francisco, Santa Gertrudis, and Guadalupe de los Sumas, the Mansos at Guadalupe de los Mansos, the Tiguas at Sacramento and Ysleta, the Janos at La Soledad, and the Tanos and Jemez at Socorro.

Revolt in El Paso

But the establishment of missions and a presidio did little to quell the unrest of the native people of El Paso. Along with Indians of northern Chihuahua, they were pushed over the edge by widespread famine in the winter of 1683-1684, caused by the strain that the influx of people to the area had put on local resources. In the spring of 1684, the Mansos revolted along with the Sumas, Janos, Julimes, Apaches, Conchos, and other groups, while the Piros, Tiguas, and a small number of Mansos remained loyal to the Spanish. Many of the disaffected were young men 20-30 years old who had been inspired by the success of the New Mexico Pueblo Revolt. In El Paso, the settlements of Socorro, Santa Gertrudis, and San Francisco participated in the revolt. Most of the missionized Mansos deserted El Paso and gathered at the rancherías of the unconverted Mansos and Sumas.

The revolt was so devastating that Cruzate was forced to move the Presidio San José closer to Guadalupe de los Mansos at the pass of the Rio Grande and gather all of the Spanish and native people who remained loyal around it for protection. It was renamed the Presidio Paso del Rio and a Spanish settlement called Paso del Norte sprung up around it. San Lorenzo, Socorro, Senecú, and Ysleta were relocated to the area of the presidio and San Pedro, San José, and Guadalupe de los Sumas were abandoned. Santa Gertrudis, San Francisco, and Sacramento had been destroyed in the revolt and were not rebuilt. Driven by hunger, the Sumas returned late in 1684 to Guadalupe de los Sumas, but many of the Mansos continued to revolt until 1686. Most of the native people who participated in the revolt never returned to the missions of El Paso. They had been brought closer together by their experience and developed a common identity as "Apache," which came to mean hostile bands that opposed Spanish ways.

In 1691, the mission of Nuestro Padre San Francisco was established for the Mansos who remained in El Paso. In early 1692, the mission of San Diego de los Sumas was established to replace Guadalupe de los Sumas. In the spring and summer of that year, newly elected Governor Diego de Vargas, 40 Spanish soldiers, and 50 Tigua and Piro warriors reconquered New Mexico. The following year, 500 Spanish and native families returned to New Mexico, depleting the populations of many of the El Paso settlements. The native population was further reduced at the end of the century by a smallpox epidemic.

Life in the Missions

The native people who remained in El Paso lived in clusters of jacal structures loosely arranged around central plazas in the vicinity of the missions. They served the friars of the missions by working their fields, tending their gardens, bringing them firewood, and performing various domestic tasks for them. They also served as wage laborers, and sometimes forced laborers, for building projects. Though corn continued to be their most important crop, the mission inhabitants adopted European cultigens and livestock, such as wheat, various fruits, cows, goats, sheep, pigs, and chickens. The Franciscan visitor general praised the work of the native peoples in his 1754 report:

The Indians of [Ysleta] have their gardens adorned with beautiful grapevines, peach trees, apple trees, and good vegetables, and the garden of the convent imitates them in providing delight to the eyes and satisfaction to the taste. All the cultivation is due to the annual presence of the gardener and the sons [of the mission], who come to the convent every week with the boys needed for the daily cleaning of the cells; they also provide the other workers – a bellringer, porter, cook, two sacristans, and the Indian women needed to grind the wheat.

–Fray Miguel de San Juan Nepomuceno y Trigo, 1754

Continuing traditions that stretched back into prehistoric times, they made tools of chipped stone, using raw materials procured from local gravel deposits. They also revived the earlier tradition of making brownware utility vessels, using local clays. They still depended to differing degrees on wild resources, such as mesquite, prickly pear, deer, rabbit, antelope, and various bird species, and used riverine species such as turtle, fish, and shellfish as supplemental resources.

In 1707, the mission of Santa María Magdalena was established for the Sumas, but they rose up in revolt against the Spanish in 1710, then fled to the Organ Mountains to join the Apaches. In 1726, three Suma groups were settled at Guadalupe de los Sumas, which had been revived, Carrizal in northeastern Chihuahua, and San Lorenzo, which had previously been a Spanish settlement. Later that year, non-missionized Sumas revolted with the Apaches and Cholomes. The Spanish established the mission of Nuestra Señora Santa María de la Caldas for these Sumas in 1730. The Sumas who settled at the mission revolted in 1745 killing one Spaniard, and again in 1749 destroying the mission and fleeing to join the other Sumas in the mountains. The mission at San Lorenzo was abandoned by the Sumas in 1754, but resettled by a different group of Sumas in 1765.

|

Artist's depiction of native people of the Rio Grande. The Sumas, characterized by tattooed or painted faces, and the Mansos, known for their distinctive red-plastered hair, were groups that early Spanish explorers encountered in the El Paso area. The Mansos were so named because their first words to the Oñate expedition were "manxo, manxo, micos, micos," which meant "peaceful ones" and "friends." Photograph of display, El Paso Museum of Archeology, by Susan Dial.  |

|

Historic Timeline

1581

Rodríguez/Chamuscado

entrada

1583

Espejo entrada

1598

Oñate entrada

1609

Santa Fe established

1659

Guadalupe de los Mansos mission established

|

Passage of the Rio Grande, as shown in a circa 1850s lithograph. When the Oñate entrada reached present-day El Paso, it found that the river flowed through a break between the mountains. Named "El Paso del Río del Norte," the pass would serve as the Spanish doorway to the West.  |

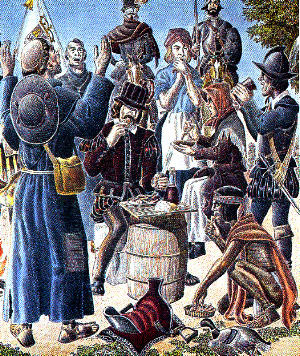

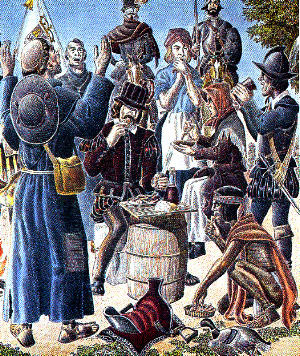

In an act of thanksgiving for their safe passage across the Chihuahuan desert, the Oñate entrada arranged for a feast to be held and asked the Mansos to be their guests. This thanksgiving was the first to be celebrated in what is now the United States, a full 23 years before that of the Pilgrims at the Plymouth Colony. Painting by Jose Cisneros, courtesy of the University of Texas at El Paso Library and the artist.  |

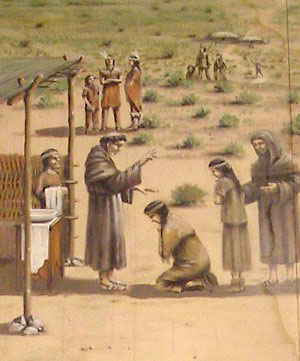

During the 1650s, Spanish priests began converting the Mansos, Sumas, and Janos of El Paso to Christianity and settling them in missions. Photo of mural at Guadalupe church in Juarez by Margaret Howard.  |

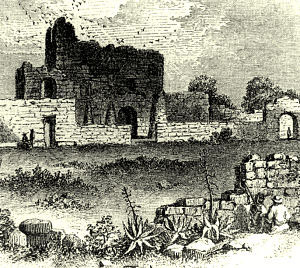

"The Plaza and Church of El Paso," painted by artist A. de Vauducourt during the 1850s, depicts the mission of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de los Mansos. Founded for the Mansos in 1659, the mission was the first to be established in the El Paso area. Today the carefully restored church stands in downtown Ciudad Juárez. Click to see the church as it appears today.

|

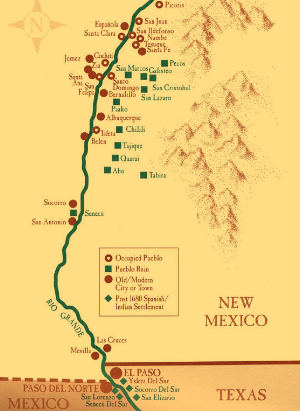

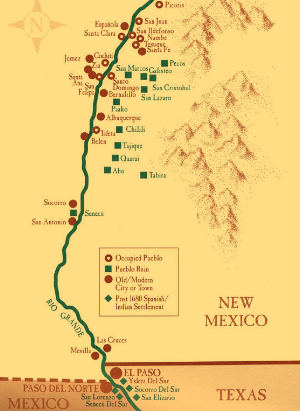

Map of significant towns and pueblos during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Following the violent upheaval, a large number of Tigua, Piro, Tompiro, Tano, and Jemez refugees and hostages accompanied the Spanish to El Paso where the missions of Corpus Christi de la Ysleta, San Antonio de Senecú, and Nuestra Señora de la Limpia Conceptión del Socorro were established for them. This map depicts Ysleta and Socorro in their present-day locations on the north bank of the Rio Grande. Image from Martinez 2000, reprinted by permission of the El Paso Community Foundation.  |

The mud-plastered jacal structures and outdoor ovens in this early 1900s photograph are probably very similar to those constructed by the native people of El Paso in the early 18th century. They were loosely arranged around central plazas in the vicinity of the missions. Photo from the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of American History.  |

Corpus Christi de la Ysleta del Sur was established for the Tiguas in 1682. Though it has been at the mercy of floods and fires over the years, the mission and church were rebuilt on successive occasions. Ysleta and nearby Mission Socorro church are the two oldest, continuously active parishes in Texas. Photograph by Susan Dial.  |

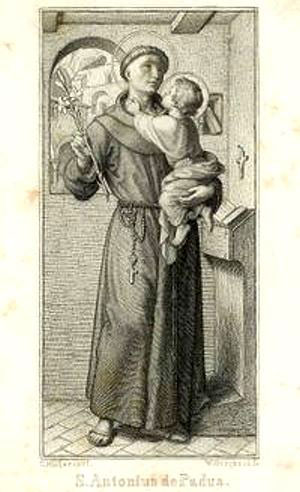

Saint Anthony of Padua, patron saint of the original Tigua mission and pueblo of Isleta, New Mexico, and the new mission and pueblo of Ysleta, Texas. Despite several changes to the mission's name throughout the years, the Tiguas always considered Saint Anthony, who died in 1231, to be their patron saint and protector.  |

Grapes growing on a Spanish arbor. In addition to their own domesticates, the native people of El Paso grew European crops, such as wheat, grapes, peaches, and other fruits. During his visit to El Paso in 1760, Bishop Don Pedro Tamarón y Romeral said of the missions that, "They maintain a large number of vineyards, from which they make generoso wines even better than those from Parras.. It is delightful country in summer.." Photograph by Carly Whelan.  |

|