Good quality potters' clay can be gathered

from exposures along many creeks in the Caddo Homeland, like

Auburn Creek, a small spring-fed tributary of the Sabine River

in Smith County, Texas. Photograph by Mark Walters.

Click images to enlarge

|

Neck banding and brushing. The last coils

of clay added to this jar were flattened and left distinct

to create a banded neck. Below the neck, the body of the jar

has been brushed to form a textured surface providing a sure

grip. Click on image to see enlarged view and the entire pot.

|

This unusual double-chambered jar obviously

was made by a master potter. The proportions and shapes are

perfect, the engraving superb. This beautiful pot must have

taken many hours to complete. Patton Engraved Jar, Historic

Caddo, after A.D. 1650. TARL collections. Click on image to

see enlarged view and detail of design.

|

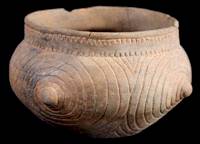

This inventive bowl has four teat-like

protruding nodes highlighted by engraved concentric circles

into which red ochre has been rubbed. This piece brings to

mind the observations made by early explorers describing geometric

tattoos they saw adorning the breasts of some Caddo women.

Note also the strong similarities with the double-chambered

jar—both pieces may be the work of a single master potter.

Patton Engraved bowl, Historic Caddo, after A.D. 1650. TARL

collections.

|

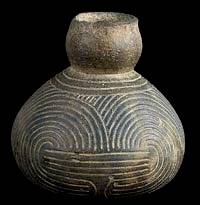

This untyped bottle has the unusual feature

of a punctated raised "mantle" on its shoulders.

This was probably added as second layer after the main bottle

was formed. Early Caddo ca. A.D. 900-1200/1300. TARL collections.

Click on image for enlarged view and for an alternate photo.

|

Detail of a tour de force example of incising

(fine lines) and incising (cut out area) by an Early Caddo

master potter. Holly Fine Engraved bottle from the George

C. Davis site. TARL collections. Photo by Sharon Mitchell.

|

Detail of typical vertical brushing on

large Late Caddo jar. TARL Collections. Click to see enlarged

view and photo of complete vessel.

|

Detail of utility vessel with random brushing

patterns, an uncommon variation.

|

Detail of trailed bottle showing area where

slip has spalled off. Click for enlarged view, details, and

photo of entire vessel.

|

Detail of somewhat crudely done engraving

on an otherwise beautifully made jar. Click to see enlarged

view and photo of entire vessel.

|

Powerful combination of incised raised

bands and brushing on this unusual vessel. Cowhide Stamped

bowl, Late Caddo, ca. 1400-1650. TARL collections.

|

|

Today pottery making thrives as a hobby, as an industry,

and as a form of artistic expression. Hundreds of books, films,

and websites exist that explain ceramic technology and pottery-making

techniques. But for those unfamiliar with the basic process and

those interested in the specific techniques favored by the ancient

and modern Caddo, here is a quick review.

The earthenware pottery made by the ancient Caddo

was made by hand using locally available materials and fired in

an open fire (as opposed to a kiln) at relatively low temperatures

(perhaps 600-700 degrees centigrade). Clay deposits suitable for

making pottery occur widely within the Caddo Homeland. In most areas

clay could be obtained easily from bluff exposures along rivers

and streams or by digging relatively shallow pits. Some clay deposits

are better suited for pottery making than others because they contain

fewer impurities or have useful properties such as the right degree

of plasticity (how easily wet clay can be shaped). Judging from

the copious quantities of Caddo pottery and from the high quality

of much of it, Caddo potters knew well where to find the proper

clays and how to prepare them.

Pure clay mixed with the right amount of water is

plastic (pliable) and can be easily formed into most any shape.

But most wet clays are so plastic that they won't hold a shape for

long before sagging and, as the clay dries, it tends to crack. A

further problem is that wet clay is very tacky and sticks to everything.

Like potters the world around, Caddo potters routinely solved these

problems by adding temper (non-plastic particles) to their clays

to help control the plasticity, to prevent drying cracks, and, in

some cases, to make their cooking pots withstand heat better. For

instance, relatively coarse temper was usually added to clays used

to make cooking vessels because the larger particles help the pots

take heat better than fine particles. The favored tempering agent

was grog (crushed potsherds). Burned and pulverized animal bone

was also used; burning is necessary in order to crush the bone properly.

After about A.D. 1300, burned and crushed mussel (freshwater clam)

shell was used as a temper by Caddo potters living along the Red

River and certain other areas. With practice, a potter learns just

how much of what kind of temper to add to create proper potter's

clay.

Once the clay mixture (paste) was ready, most Caddo

pottery was made using the coil method. First a flat disk was formed

that would serve as the base of the vessel. Rope-like fillets of

clay were then gradually coiled around the disk and mashed together

to form the vessel walls. The vessel walls were thinned, smoothed,

and compacted by the use of fingers, smooth river pebbles, shaped

sherds, or other tools. Redcorn uses dried gourds of various sizes

as anvils that she holds on the inside of a pot while she applies

a wooden scraper or wooden paddle on the outside to weld the coils

together, compact the clay, and form a smooth, even surface.

An experienced potter can make a simple bowl rather

quickly, in less than an hour. Large or complicated vessels take

many hours or even days to make because of the need to let the lower

parts partially dry before they are strong enough to add the upper

parts. When making larger pots with several different parts (like

long-necked bottles or vessels with tripod feet), Jereldine Redcorn

finds it best to "put it [the half-made pot] away for a few

days. When you come back to it, all of the sudden it is wonderful."

What she means is that curing the still-damp pot (she wraps hers

in a plastic bag) makes it easier to work with when adding on necks

and other elements. "The clay remembers," she says, and

holds its form. She suspects ancient Caddo potters did the same

thing, perhaps by wrapping their pots in wet animal skins. "You

can make some pots much quicker, by just keeping at it, but it's

hard to get wet clay to behave the way you want it to."

Finishing the form of the pot is only the first step.

Caddo potters seemed to have delighted in finishing and decorating

their pots in many different ways. While the pot was still damp,

the surface was sometimes textured by brushing (useful for making

water jars and cooking vessels less slippery) or by pinching it

to form ridges. Other favored decorative techniques at this stage

included the use of a thin, sharp tool (like a flint flake) to incise

narrow lines, pointed sticks to incise broader lines or create deep

punctations, fingernails to create curving impressions, and hollow

pieces of cane or reed to create small circles. Another technique

used in later prehistoric times involved the addition of small shaped

clay fillets (appliqué) or protruding "nodes" of

clay on the outside of the vessels to create raised relief.

Then the vessel was allowed to dry to what potters

call the green-ware stage. For the finer vessels, a second thin

layer of fine, untempered clay mixed with a red pigment called a

slip was sometimes added at this stage. The slip layer gave the

vessel a smooth, uniform appearance and sometimes a more desirable

color. Redcorn adds really fine clay slips to most of her pots to

enable her to create highly polished, mirror-like finishes that

those who buy her pottery seem to prefer. Ancient Caddo potters,

however, usually stopped well short of achieving highly polished

surfaces.

When the pot is completely dry (or almost so), the

green-ware vessel is burnished by wetting small areas of the outer

surface and rubbing the outside of the vessel with a small smooth

river pebble. This is a tedious and slow process, but one that results

in a vessel that has a lustrous appearance and a harder and less

porous exterior surface. Burnishing was usually done in parallel

strokes, up and down or side to side, leaving parallel burnishing

marks and a slightly uneven surface. If the potter was willing to

work hard enough and long enough, the burnishing marks could be

obliterated and the surface would become completely smooth and highly

polished.

Jereldine Redcorn found that learning how to properly

burnish a pot was one of her biggest challenges. Trials and errors

later, she now understands that burnishing must be done as a single

step without stopping. It takes her an hour to an hour and a half

to burnish a medium-sized bottle. She paints on small patches of

watery clay slurry and burnishes these quickly, adding one finished

patch to the next so she can make the burnishing look seamless.

Once the green-ware pot is completed and allowed to

thoroughly dry for several days, it is ready to fire. Ancient Caddo

pottery was apparently fired in an open bonfire, probably fueled

by wood and brush. Like most traditional potters, the Caddo women

probably fired more than one pot at a time. Whether the pots came

out with clear, bright, oxidized colors (red, yellow, light brown)

or dark, dull, reduced colors (gray, black) depended on how hot

the fire was and on the placement of the pots. (Clay type also factors

in to final color.) If the pots stayed hot after most of the fuel

had burned up, thus allowing air to reach the pots, they would become

oxidized. If the pots cooled while still covered by ash or up against

another pot, then they would have fire clouds and dark colors.

Redcorn likes to fire her pottery at a somewhat higher

temperature that her ancestors, in part because she usually uses

a higher quality commercial clay than her forebearers had access

to. She fires up to 15 pots at a time in a large metal barrel filled

with seasoned oak for intense heat and some fast-burning wood like

pine to get things going quickly. Her resident "wood expert,"

husband Charles Redcorn, gathers and prepares the wood. He also

helps her stack the pottery on different levels within the big barrel

to keep the pots from touching one another, to eliminate most fire

clouds. When she wants a black finish, she pours in a mix of sawdust

and powdered manure at the end of the firing to smother the fire

and create a reducing atmosphere.

After firing, ancient Caddo potters apparently engraved

some of their pots using a sharp flint tool like those used for

incising. Engraving leaves slightly rough-edged marks that cut through

rather than displace the outer layer of the pot through the slip

(if present). In contrast, incision and punctation displaces the

still-damp clay and leaves tiny ridges where the clay is pushed

up. The Caddo potters seem to have been very fond of incising and

engraving. They found many different ways to create pleasing decorative

effects by incising or engraving lines of different widths and depths,

adding tick marks, cross-hatching, parallel lines, curvilinear patterns,

and so on. To make the incised and engraved designs stand out, the

potters often rubbed mineral pigments, such as red ochre or white

kaolin clay, into the designs.

Jereldine Redcorn engraves her pottery after it is

polished and thoroughly dried, but before it is fired. Some archeologists

think the ancient Caddo did it that way too, although others hold

that engraving was done after firing. Perhaps it is mainly a question

of firing temperature and hardness. Vessels fired at higher temperatures

are just too hard to engrave, according to Redcorn. Becoming proficient

at engraving was the hardest thing she had to learn. She used bone

awls at first, but they kept wearing out and constantly needed resharpening.

Pieces of flint work, but are hard to hold on to. So today she usually

uses a metal awl. Part of the challenge of engraving is simply to

create nice even lines, particularly when they are closely-spaced.

She finds cross hatching to be "very tedious" and has

learned to take frequent breaks to let her hand rest.

But the real art of engraving lies in planning and

executing the design. For the first few years, Redcorn "tried

too hard." She wanted to make her designs perfectly symmetrical

and spent a lot of time trying to lay out each design (with a pencil)

before beginning engraving. With experience she has learned "to

just let things flow." She may trace out the major design elements,

but once she starts she does not try to make it perfect, "just

look good." Once she has used a design enough times, "it

becomes mine" and she no longer has to think so hard about

it. "I've learned to see the whole picture, the whole design,

and adapt it to fit each pot."

The photographs accompanying this exhibit illustrate

these and some of the other variations and techniques used by Caddo

potters of yesterday and today.

|

Closeup view of a clay bank along Auburn Creek, Smith County,

Texas. Impurities in some clays must be removed by hand or sieved

out before good pottery can be made. Photo by Mark Walters.

|

This untyped bottle is nicely formed, but

has rather poor quality engraving. The dark bottom and irregular

fire clouds on the neck suggest that it was fired in an upright

position. Middle to Late Caddo ca. A.D. 1200-1650. TARL collections.

|

Detail showing combination of thin incised

lines executed while pot was still green; and incised areas

carved out after the pot was fired. Holly Fine Engraved bowl,

Early Caddo, ca. A.D. 900-1200. TARL collections. Click to

see enlarged view and photo of entire vessel.

|

Bottle apparently engraved by a young potter

with a shaky hand. Antioch Engraved bottle, Middle Caddo,

ca. A.D. 1200-1400. TARL collections. Click to see enlarged

view and photo of entire vessel.

|

Detail of beautifully decorated jar. The

rim has been ticked, the neck has rows of diagonal punctations,

and the main body has spiraling incision. All these decorative

techniques were done before the vessel was fired. Foster Trailed

Incised jar, Historic Caddo, after 1650. TARL collections.

Click on image for enlarged view and photo of entire vessel.

|

The flowing shape of this bottle suggests

the form of a squash or gourd. Unlike most bottles, the joint

between neck and body was made obvious by leaving it unsmoothed.

Perhaps the potter just liked the effect. Wilder Engraved

bottle, Late Caddo, ca. 1400-1650. TARL collections. Click

on image for enlarged view and detailed view of shoulder.

|

Magnificent example of near perfection

in decorative design and technique. Keno Trailed bottle, Historic

Caddo, after A.D. 1650. TARL collections. Click on image for

enlarged view and detailed shot of central design.

|

Detail of fine trailing (broad incised lines) showing how the

potter's tool displaced the still-wet clay. Click for enlarged

view, details and photo of entire vessel. |

Detail of appliqué on Late Caddo jar. Click to see enlarged

view, details, and photo of entire vessel. |

Detail of rather sloppy incising done while the clay was still

very wet. Click to see enlarged view, details, and photo of

entire vessel. |

|