Reviving a Lost Tradition

| It began one warm day in the second week of June, 1991, when members of the Caddo Culture Club walked into the Museum of the Red River in Idabelle, Oklahoma. The club had formed several years earlier under the leadership of Lowell "Wimpy" Edmonds to bring together tribal members interested in preserving traditional knowledge, the Caddo language, and traditional forms of expression such as dance. They were visiting the area at the invitation of the Texas Archeological Society during the Society's annual field school, held that year at the Roitsch site, an ancient Caddo settlement on the Texas side of the river. The archeological group had asked the Caddos to come see what they were doing and perform traditional Caddo dances. This, in itself, was a first and an important step toward a closer and more respectful relationship between Texas archeologists and the Caddo Nation. But for the present story the real eye-opener came when the Caddos visited the museum. Entering the museum, the tribal members were stunned to see hundreds of often spectacular pottery vessels made by their ancestors on display and in storage. Vessel after vessel, bowls, bottles, jars, fancy fine wares, and everyday cooking pots. Tribal elder Randlett Edmonds, who was in his 70s, turned to his friends and said "I haven't seen this before, I did not know," recalls Jereldine Redcorn.

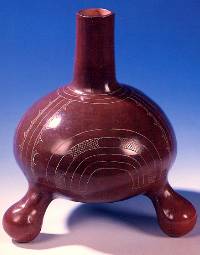

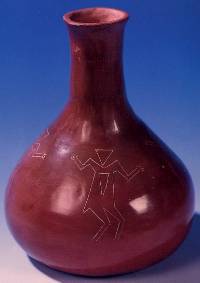

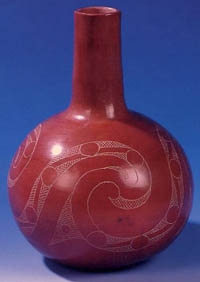

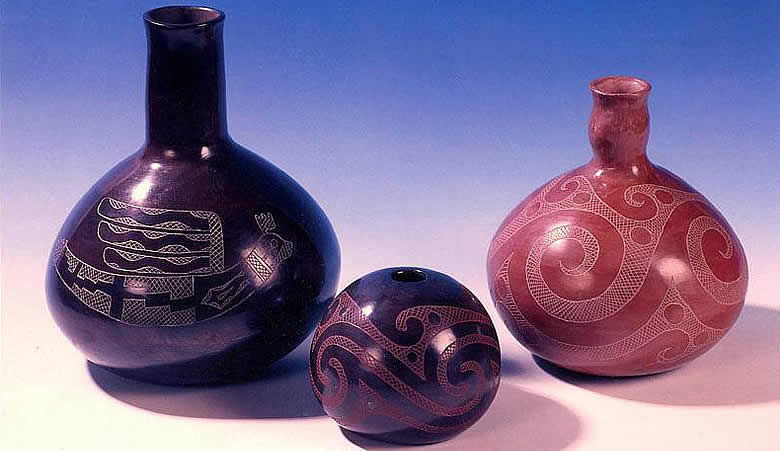

Reviving the lost tradition of making Caddo pottery proved anything but easy. Of those who vowed to learn that day, only one was young enough and determined enough to be able to make it happen. Somehow the ancient pots in that museum spoke to Jereldine Redcorn. Not in so many words, but in ideas, in feelings, in shapes and forms forgotten, and in those marvelous designs created in clay so long ago. Caddo pottery gave her an instant connection to an ancestral past she had never really understood before. But unlike earlier Caddo potters, Jereldine had no knowledgeable elders to turn to for guidance, no tight-knit group of female potters to work with and learn with. So she set out on her own path, to find her peoples' way back to the lost tradition. Her brother had made simple coiled pots, so he spent a day with Jereldine showing her what he knew. She read a few books, but mainly she just started making pots. Her first pots were "really ugly" she says today with a laugh, but she persisted. Her main inspiration came from her ancestors through the Caddo pottery they had made long ago. She was astounded to learn how many Caddo pots had been dug up from the graves of her ancestors. She visited more museums and talked with archeologists. They sent her books and articles. From TARL came a rare copy of the 1962 Handbook of Texas Archeology, with page after page of black and white photographs of Caddo pots. "Please donate it to the tribe when you do not need it anymore," they told her. "That was 12 years ago and I'm still using it today" says Redcorn, "so I guess I'll have to put it in my will to give it to the tribe." Slowly, awkwardly, and painfully at times, she learned to make Caddo pottery. Some of the steps, like burnishing and engraving, were "incredibly hard to learn" and took her many years to master. But she kept trying and kept getting better. And pottery-making skills were not all she had to master.

Born of a Caddo father and a Potawatomi mother, Jeraldine Redcorn was raised in Colony, Oklahoma, on her grandmother Francis Elliot's Caddo land allotment. "We were 15 miles from most of the other Caddos, which back then [1940s and 1950s] was a long way. We lived closer to some of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people." Apart from what she learned attending occasional dances, she did not know much about her Caddo heritage early in life. The quest for higher education took her to Plainview, Texas, where she earned a BS from Wayland University and then to State College, Pennsylvania, for her MA from Penn State. She married, raised a family, taught school, worked in an early Oklahoma Indian Headstart program, served on the Caddo Tribal Council, and was the founding director of Oklahoma's annual Red Earth Festival. She taught high school geometry in Oklahoma City for many years before her recent retirement and today lives with husband Charles Redcorn (Osage) in nearby Norman. Having learned how to make Caddo pottery, one of Jereldine's most important goals is to pass on the hard-won knowledge she has gained to other Caddo women, especially younger women who could keep the revival going. She has given lessons to several dozen women, including her daughter, but so far she hasn't found an apprentice who has both the determination and the love of pottery. "It's a difficult path, she laments, "it takes a lot of time and hard work." "But," she says wistfully, "it would be so much fun to have a group of women working with me. I get so excited now and it's just me. My fervent hope is to keep the tradition going." So she keeps moving forward, making pottery when she can and working to perfect her craft. Sometimes life intervenes and she must go months without making pottery. "I feel like something is missing, like a part of me is not there." As soon as her hand are wet with clay again, her world feels right and the passion comes right back. Redcorn's husband, Charles, is her "wood expert" who fashions pottery tools for her, gathers the right kind of fuel wood, and helps her on firing day. He more than anyone has shared her journey. She also credits archeologists for encouraging her and helping her learn her craft. Don Wyckoff from the Sam Noble Museum at the University of Oklahoma and Lois Albert from the Oklahoma Archeological Society were among the first to see her early pottery. "I was just starting and I was not any good, but they were kind and gave me hope that I could do this." She also visited the museum where they gave her special access to the Caddo pottery collections so she could study closely the tell-tale marks of the ancient maker's pots. She also visited Jim Corbin at Stephen F. Austin University in Nacogdoches, Texas. Corbin, a potter himself, freely shared what he had learned about Caddo pottery with Redcorn. "He sent me home with sacks of Caddo clay and new ideas." Archeologists were also the first people who wanted to buy her pottery. "I would go to the Caddo Conference every year and bring what I had made." At first she did not know anybody. She and Charles attended a few talks and wondered how the archeologists "could sit there and listen to some of that stuff" (the normal reaction of any sane, non-archeologist and that of many archeologists as well to mind-numbing details delivered in monotone.) Thankfully, some of the talks she heard were more inspiring and she realized some of the archeologists were as passionate about Caddo pottery as she was. Soon she made friends and found that Caddo archeologists (archeologists who study Caddo sites) were keenly interested in what she was doing. They not only liked her pottery, but they bought it. They also showed her more pictures, gave her more books, and started asking her to replicate their favorite archeological pieces. The Redcorn pots photographed for the modern Caddo pottery gallery were all bought by Austin-based archeologists at Caddo Conferences. Redcorn did not, of course, start making Caddo pottery to make money. She really had no idea anyone would think enough of her pottery to buy it. "Up here on the Plains," she says, "there really is not a pottery culture today. There are some good Cherokee potters, but it's not like the Southwest." Vibrant local pottery culture or not, today Redcorn's pottery commands hundreds of dollars and is on display in museums and in the homes of archeologists and art collectors. Having retired in 2004 from her longtime job as a high school geometry teacher, she now is able to fully concentrate on her craft. In the Making Caddo Pottery section you can read more about what Jereldine Redcorn has learned while following her vision to revive the lost Caddo pottery tradition. And visit the Pottery Gallery to see more of her pottery. For contact information, see Credits and Sources. |