Odd little pot with four, spiked

handles. Nash Neck Banded jar, Late Caddo, ca. A.D.

1400-1650. TARL collections.

|

This olla has a short neck with a

flaring rim and a small mouth. These features suggest

that it served as a water jar or dry storage jar that

could be sealed by tying a skin cover over the mouth.

Hodges Engraved olla, Late Caddo, ca. A.D. 1400-1600.

TARL collections

|

Example of the use of white pigment

(probably kaolin) to fill the engraved lines, thus heightening

the contrast with bright red bowl. Ripley Engraved bowl,

Late Caddo, ca. 1400-1650. TARL collections.

|

Small engraved bottle with highly

unusual "spiked gaping mouth." Taylor Engraved

bottle, Late Caddo, ca A.D. 1400-1650. TARL collections.

|

Looking down into small triangular

engraved bowl. Untyped, Late Caddo, ca. A.D. 1400-1650.

TARL collections. Click on image for enlarged view and

alternative view.

|

Hodges Engraved bottle with unusual

oblong form and pairs of nodes at both ends. Late Caddo,

ca. A.D. 1400-1650. TARL collections.

|

Miniature pottery probably made for

children. Untyped, Historic Caddo, after A.D. 1650.

TARL collections.

|

These decorated jars are believed to have been made at

the Brazos Reserve in the 1850s. These two and another

similar pot are in the Brooklyn Museum and were collected

by medical doctor. The vessel form and decorative designs

are immediately recognizable as Caddo in origin and probably

derived from one of the Kadohadacho groups. They show

that the fine ware tradition survived into the mid-1850s.

Drawn by Nancy Reese. From Perttula, 2001. |

|

Why Study Caddo Pottery?

Why do the archeologists who study the ancient

Caddo spend such an inordinate amount of time and effort excavating,

reconstructing, and studying Caddo pottery? For archeologists,

Caddo pottery is the prime evidence used to identify and date

ancient traces of the Caddos' past. Lacking potsherds, we

could scarcely identify the vast majority of Caddo archeological

sites as being Caddo. While there are many other distinctive

kinds of archeological evidence of Caddo life, such as house

patterns, pottery remains indispensable for understanding

the past for three main reasons.

First, the ancient and early historic Caddo

were superb potters and made and used lots of pottery. Sites

representing small farmsteads where a single family once lived

for short durations will have hundreds of potsherds. Villages

and ceremonial centers often have tens or hundreds of thousands

of potsherds and, in graves, many whole or almost whole pots.

Secondly, pottery is relatively durable and can often be identified

by style and form even when broken into small fragments. Thirdly,

Caddo pottery is tremendously varied—different forms

or shapes, different decorative designs, different colors,

different finishes, different sizes, and so on. Further, pottery

styles and preferences changed through time and varied from

place to place within the Caddo Homeland. Given the right

sherd, an expert often can tell approximately where the pottery

was made and how old it is, give or take a few centuries (or

sometimes a few decades). This is because we know what whole

Caddo pottery vessels look like.

The Caddo pottery tradition was tied to the

Caddo funerary tradition of placing whole pottery vessels

in the graves of departed loved ones. The vessels may have

contained food and drink to accompany the deceased in the

afterlife or they may have been prized personal possessions

(or both). Some burial pottery is obviously worn from use,

but other vessels show no wear and look like they were interred

in a fresh, newly made condition, perhaps representing gifts

from loved ones. Whatever the case, the ancient Caddo must

have considered pottery important because they included pottery

vessels as grave offerings more frequently than any other

non-perishable material. Clothing, mats, baskets, and objects

made of wood may have been more common, but these things usually

decay quickly. (The typically acidic soil in the Caddo Homeland

destroys virtually all organic materials, including human

bones, over time.)

Whole pots are also found in other contexts

besides graves, especially on the floors of houses. For instance,

over 30 vessels of various sizes and forms were recently found

on the floor of a house at the Tom Jones site in the Little

River Valley in Arkansas. Most of these were broken by the

collapse and burning of the house. (Many pots included as

grave offerings are also broken.) For the archeologist, a

reconstructed pot is every bit as informative as a never-broken

vessel.

The ancient Caddo tradition of including offerings

of pottery in graves has led to the excavation of thousands

of Caddo graves, some by archeologists and many more by looters

("pothunters") seeking pottery for personal collections

and, increasingly, to sell for profit. No one really knows

how many, but tens of thousands of vessels have been removed

from Caddo graves. Many are traded or sold on the antiquities

market in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Some spectacular

Caddo vessels are rumored to have sold for over $20,000. Even

ordinary Caddo pots can bring hundreds of dollars on the market.

The desecration of Caddo cemeteries has long

been a source of anguish to Caddo people (and Caddo archeologists).

As explained in the "Graves

of Caddo Ancestors" section , the Native American

Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990 has

put the fate of most of the Caddo pottery vessels excavated

from graves by archeologists in the hands of the Caddo Nation

of Oklahoma. (NAGPRA applies to federal agencies, federally

funded or permitted excavations, on federal and tribal land,

as well as to all museums and institutions that have received

federal funding. While this effectively covers most grave

goods excavated by professional archeologists, the law does

not pertain to graves dug up on private land or grave goods

in private hands.)

Caddo people are conflicted—they want to

honor their ancestors, but they are not sure that reburying

all grave goods and bones in mass or separate graves hundreds

of miles from their original resting places, as some tribes

have chosen to do, is the right thing to do. Another possibility

being considered by the Caddo is to expand their own tribal

museum so that pottery vessels and other grave goods can be

treated properly and preserved for future generations as sources

of pride and knowledge about the past.

Regardless of what happens in the future, Caddo

pottery was important to the ancient Caddo, it is important

to the Caddo Nation today, and it is important to anyone who

wants to understand ancient Caddo history.

Origin and Development of the Caddo Pottery Tradition

When we say that the Caddo pottery tradition

began about A.D. 800, we do not mean to imply that earlier

ancestors of the people known today as the Caddo were not already

making pottery. Clearly they were. But we do not know exactly

how, when, or even where, the Caddo pottery tradition was

first established. Partly this is because it is often impossible

to recognize the origin or beginning of any complex phenomenon

in the ancient past. And partly it is because we have so few

well-excavated and well-dated Late Woodland and early Caddo

sites.

In part, the Caddo pottery tradition grew out

of the Fourche Maline pottery tradition that developed during

the Middle and Late Woodland periods. Like early Caddo pottery,

Fourche Maline pottery was usually grog or bone tempered and

it was sometimes burnished. But Fourche Maline pottery was

rarely decorated and it is very thick-walled in comparison

to the Caddo fine wares. Vessel forms are also very different

between the two traditions. Some of the favorite Caddo decorative

techniques, incising and punctating, are found on Fourche

Maline pots, but most of the designs are very simple.

The inspiration for these decorative techniques

almost certainly lies to the southeast in the Woodland cultures

of the lower Mississippi Valley (LMV). Beginning with Tchefuncte

pottery (800-200 B.C.) and continuing on into the Middle Woodland

period (200 B.C. to A.D. 500) with Marksville pottery, incised,

stamped, and puncated designs were common. Trade pieces of

Tchefuncte and Marksville pottery are found in the Caddo area.

By Late Woodland times (ca. A.D. 500-800/900) Fouche Maline

potters began to copy the designs of Coles Creek pottery from

the LMV.

The origin of the technique of filling the engraved

patterns with pigments and the origin of the distinctive early

Caddo vessel forms—long-necked bottles and carinated

bowls—is not known. We do not see clear precedents in

the Woodland-period pottery of either the Caddo Homeland or

the Lower Mississippi valley, or the central Mississippi valley,

or the Arkansas Basin. Therefore, we suspect that one of two

things happened: ancestral Caddo potters invented these techniques

for themselves or they borrowed the ideas from distant cultures.

Archeologists have struggled with explaining

the origin of highly specific behaviors for decades—are

these "independent inventions" or the result of

the "diffusion" (spread) of ideas or of things like

domesticated plants? In the 1940s, Alex Krieger and Clarence

Webb, like many of their contemporaries, favored the diffusion

explanation. These Caddo scholars and other prominent American

archeologists of the day pointed to seemingly close parallels

between Caddo pottery and the pottery of certain Mesoamerican

cultures in what is today Mexico and Guatemala. They could

not explain how the contact between these very different and

widely separated (in space and time) cultures took place.

Nor could they point to positive evidence of direct contact,

such as the finding of a pot made in Mesoamerica at a Caddo

site (or vice versa).

Caddo archeologists today reject the notion

of a Mesoamerican origin and see the Caddo pottery tradition

as an independent development influenced only by neighboring

peoples living mainly to the east along the Mississippi River

and along the Gulf coast. The diverse Caddo pottery tradition

bears witness to the obvious inventiveness of Caddo potters

and their willingness to experiment. It is worth pointing

out that there are a great many cases across the world of

the obviously independent invention of specific forms of pottery

making and decoration. Carinated pottery, long-necked earthenware

bottles, and engraved designs with pigment all occur in many

places in the world that are separated by thousands of miles

or thousands of years (or both). For instance, carinated pottery

forms similar to those of the Caddo tradition are also found

in Mesoamerica, South America, Africa, Europe, and Asia.

Thus it seems likely that about 1200 years ago,

ancestral Caddo potters began to develop their own distinctive

pottery tradition by combining the established ways of making

pottery (the Fourche Maline tradition and probably that of

the Mill Creek and Mossy Grove traditions) with inspirations

from neighboring peoples, and creative new ideas cooked up,

so to speak, in Caddo villages by Caddo potters. By A.D. 1000,

the Caddo pottery tradition was firmly established and distinct

from all others.

While some variation is apparent across the

region, Early Caddo pottery seems to vary much less from place

to place than would be the case a few hundred years later.

Compared to the Caddo potters in later times (after A.D. 1400),

early Caddo potters used fewer decorative techniques, applied

decoration to larger areas of the surface of their fine wares,

and left most of their utilitarian wares undecorated. They

also favored bowl forms, especially carinated bowls, and bottles,

although they made jars, plates, effigy vessels, and compound

bowls, among other forms. Decorative designs were typically

curvilinear, rectilinear, and horizontal. The relative homogeneity

of early Caddo pottery is thought to be the result of broad

and extensive social interaction among Caddo groups

After A.D. 1400, Caddo pottery became more diverse

in form and, especially, in decorative technique and style.

Caddo potters developed (or borrowed) new decorative techniques

including appliqué, trailing (wide incisions, often

curved), brushing, and a great many combinations. Intricate

scroll designs with ticked lines, incised circles, negative

ovals and circles, triangles, and ladder designs are all common

in late Caddo pottery. Jar forms seem to have become more

important and bottles somewhat less so. New specialized vessel

forms such as rattle bowls and "tail-rider" effigy

bowls appear, the latter closely resembling vessel forms in

northeastern Arkansas. Very rare examples of Caddo pots made

in the style of Mississippian head pots are also known.

More than anything, the Late Caddo period was

the time during which many local styles were created. In part

this probably represents higher population levels (more people

making pottery), but it also seems to reflect the existence

of more social groups, each with its own local pottery tradition

handed down and elaborated on from generation to generation.

It is likely that the local styles were quite intentionally

made different from one another as an expression of the identities

of each Caddo community. Alice Cussens, daughter of Mary Inkinish,

told a WPA interviewer in 1937 or 1938: "each clan had

its own shape to make its pottery. You could tell who made

the pottery by the shape." [From David La Vere, 1998,

Life Among the Texas Indians, where her name is given

as Mrs. Frank Cussins. She was born in about 1885, by which

time neither Caddo pottery making nor Caddo clans survived

intact. Hence her words must reflect what she learned from

her mother.]

The invasion of European peoples and the attendant

catastrophic impacts on the Caddo (population loss, forced

moves, changing economy, etc.) brought about a relatively

quick end to the Caddo pottery tradition. For a time in the

late 17th and early 18th centuries Caddo women were able to

keep making beautiful and distinctively Caddo pottery, but

by the close of the 19th century, only vestiges of the tradition

survived. The last Caddo pottery of the original tradition

was apparently made in the late 1800s after the move to Oklahoma.

Today, as can be seen in other sections of this

exhibit, there is hope that the Caddo pottery tradition will

be revived, at least as an art form. Of course the tradition

will never be the same without the existence of the societies

that kept it going. Modern Caddo people use store-bought pots

and pans, just like everybody else in the developed world.

|

Finely crafted Holly Fine Engraved

bowl, Early Caddo, ca. A.D. 900-1200. TARL collections.

Click to see top view.

|

Looted Caddo cemetery in northeast

Texas. Photo courtesy Texas Historical Commission.

|

Late Caddo bottle with poorly smoothed

neck bands and faint ladder-like design on main body.

Hume Engraved bottle, ca. 1400-1650. TARL collections.

Click on image for enlarged view and detail of neck.

|

A rare Late Caddo "head pot"

from southwestern Arkansas. The Caddo master potter

who made this extraordinary piece obviously copied a

typical Mississippian head pot, but decorated it with

Caddo style engraving rather than painting. The engraved

designs may mimic facial tattooing. Courtesy Picture

of Records, original in the Henderson State University

Collection, Arkadelphia, Arkansas.

|

These peculiar little vessels are

rattle bowls. The protruding nodes are hollow and contain

small pebbles or rounded pieces of clay that rattle

when the bowl is shaken.

Late Caddo, ca. A.D. 1400-1650. TARL collections. Click

to see enlarged view and close up of one bowl. |

Large tear-drop or gourd-shaped Sanders

Engraved "seed pot," so-called because of

the small restricted mouths. In fact, there is no definitive

evidence that such vessels were used to store seeds.

This one is much too thin to have been a water jar and

it does have small holes near the rim that were probably

used to secure a lid, lending support to the seed pot

notion. Middle Caddo, ca. A.D. 1200-1400. TARL collections.

Click to see enlarged view and detail of rim.

|

Typical Fourche Maline jar with thick

walls and a shape resembling a flower pot. This Williams

Plain pot is from the Crenshaw site, Miller County,

Arkansas. Photo by Frank Schambach.

|

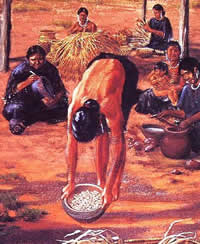

Detail of artist's depiction of daily life in an Early

Caddo village. The woman on the far left is engraving

a bowl. Courtesy artist George Nelson and the Institue

of Texan Cultures. |

|