Newcomers: |

|

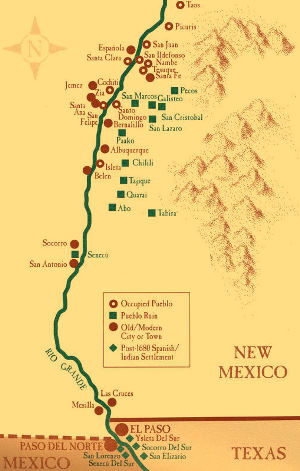

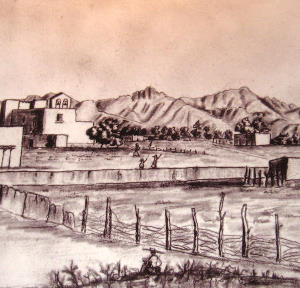

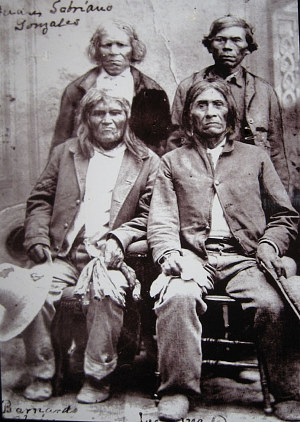

In addition to the native peoples that the Spanish first met during their expeditions through the Trans-Pecos in the 1580s—such as the Jumanos and Patarabueyes—and the other resident nations that they came to know better in their subsequent travels to and from New Mexico and settlement of El Paso—such as the Mansos, Sumas, Chisos, and Conchos—some groups whom the Spanish found in the Trans-Pecos or who settled in the region during the era of European exploration and settlement were not native to the region. These include the Tigua of Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, the Mescalero Apache, and the Piro. Here we highlight the Tigua. Migrations of native groups from one region to another were not exclusive to the era of European colonization and settlement. Archeologists can document migrations in prehistoric times as well, notably around A.D. 1450 when the prehistoric pueblos in the El Paso region were abandoned. However, the causes of prehistoric migrations are subject to scholarly debate. In contrast, the causes for the arrival of the Mescalero Apache, Tigua, and Piro are well documented in historical records. The Tigua and Piro entry into the region was in 1680 and was directly tied to events in New Mexico that resulted from Spanish colonization. The Mescalero arrival was the result of the push of the Comanche into the Southern Plains, a region that the Mescalero had claimed as theirs. TiguaThe name Tigua (pronounced tea-wha) has multiple meanings. It is a language (usually spelled Tiwa), a province (Tigua, Tiguex, Tiguas, Tigues, Tirguex), and a people (Tiguas, Tiguex, Tigues, Tirguex). All were first named in the documents of the 1540 Spanish expedition taken by Francisco de Coronado from Mexico City to modern Arizona, New Mexico, and the Southern Plains. Coronado, using his own money and money from wealthy backers, and the men he enlisted to go with him all expected to find rich cities that they called the Seven Cities of Cibola—cites with rich holdings that held gold, turquoise, hides, and other goods that could be traded and taxed to bring each of them, including the Spanish King, much wealth. Above all, they wanted to find large cities with bustling populations. People were a key to their pursuit of wealth, not because they wanted slaves to work for them on large ranches or mines although they would certainly have viewed such as a side benefit, but because they and their king would need a ready and dependable source of goods and taxation to annually re-fill their coffers. As stated in the book Documents of the Coronado Expedition, 1539-1542, They Were Not Familiar with His Majesty, nor Did They Wish to Be His Subject: We cannot stress enough that the Coronado expedition and scores of others like it that took place during the 1500s were not primarily exploring parties bent on simply charting the unknown. Empty land was of little interest to them, regardless of its mineral or agricultural potential. Instead they sought out people—specifically, people who possessed or produced high-value goods that might be appropriate by means of a kind of taxation. Hints of such goods and populations north of Mexico had been in the written and verbal accounts given by Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca and his companions when they arrived in Mexico City in 1536. (See Learning from Cabeza de Vaca.) Shipwrecked on the Texas Gulf Coast in 1528, they trekked barefoot and naked from South Texas to northern Mexico, and ultimately to central Mexico. There, these weary travelers recounted tales they had heard of large, wealthy cities north of the Patarbueyes whom they encountered along the Rio Grande in the vicinity of modern Presidio, Texas. These hints were sufficient for the Viceroy of Mexico, Antonio de Mendoza, to send the Franciscan priest Fray Marcos de Niza and Esteban Dorantes (who had been one of Cabeza de Vaca’s companions) north to explore the possibility of “Cibola.” Cibola was a land where these cities could be found. Two recent books by the Flints detail the events that transpired after Cabeza de Vaca and his companions arrived in Mexico City and present original Spanish documents relating to the expedition. The documents include testimony given in Mexico City during an investigation into the way Coronado and his men treated the Indians, particularly the Indians who lived in the Tiwa pueblos where massive death and suffering occurred. The events of the 1540 expedition and subsequent Spanish colonization affected the Tigua in profound ways and set in motion events that led to their presence in the Trans-Pecos of Texas. The initial discussions of the Tigua in the documents of the Coronado expedition describe the Tigua’s first full-blown encounter with the Spanish in the cold, harsh winter of 1540. Coronado and his men’s first view of the pueblos found across the Southwestern US was at the Hopi pueblos. There, they expected large populations, wealth, and minor resistance to their superior fighting ability. Disappointment came quickly. The expectations of Fray Marcos de Niza were not found. Writing to the viceroy, Coronado expressed his disappointment: It now remains for me to give an account of the seven ciudades [cities], the reinos [the kingdoms], and the provincias [provinces] about which the father [Fray Marcos de Niza] reported to your Lordship. So as to not beat around the bush, I can say truthfully that he [Fray Niza] has not spoken the truth in anything he said. Instead, everything has been quite contrary, except the name of the ciudad and the large stone houses. Although [the houses] may be decorated with turquoise, [they are made] from neither mortar nor brick….The seven ciudades are seven small towns, all consisting of the [sort of] houses I describe [here]. They are all located within close proximity….All are called the reino of Cibola. Each one has its own name and no single one is called Cibola. Coronado added that the Hopi had few possessions. If they had great quantities of turquoise, little of it was found in the “cities.” The people wore few clothes and, other than quantities of corn, only two emeralds were found. Obviously, these were not the riches expected. As a side note, imagine a stranger arriving at your door and demanding to see your “goods” or “riches.” Today, we would be aghast. In retrospect, it is clear that the Hopi, Tigua, and other native peoples the Spanish visited on the expedition were also aghast. In the same report Coronado expresses concern about the lack of pastures, raisins, sugar, oil, or wine. Hearing from natives and his own men that other ciudades and reinos existed east of the Hopi towns, Coronado first sent Capitan Hernando de Alvardo east to find these places and report on them to him. Alvardo first found Acoma [Acuco], then Triguex, then Cicuyc [Pecos]. Later don Garcia Lopez de Cardenas traveled east to prepare a place for Coronado in the province of Tiguex, a region where the Tigua had lived for over 300 years. To understand the feelings and subsequent actions of the Tigua, the sequence of events is important. Coronado wanted to have sufficient quarters for he and his men. On the one hand, we can commend Coronado for his concern for his men; on the other hand, we can recognize that in his concern for his men, he had little to no concern for the Tigua. Thus, his men told the residents of one Tiguex pueblo to decamp and his men settled in that pueblo. As a result, the Tigua of that pueblo were forced to leave and they were “given shelter in the other pueblos of their friends.” Clearly, this first encounter with the Spanish was not a happy one for the Tigua. Not only had the Spanish forced the residents from one of the 12 Tigua pueblos, when about 300 of Coronado’s men arrived at the Tiguex province in that early winter of 1540 they were not prepared for the cold. Snow in unexpected quantities had plagued their journey east across modern New Mexico from the Hopi villages. Arriving at the Tiguex province that bordered both sides of the Rio Grande in central New Mexico, the general in charge told one of the Tiguex leaders: “to furnish him [with] 300 pieces of clothing or more. This he had need of to give to his people [i.e., the Spanish].” The Tigua at first refused. After all, it was a harsh winter for them too. Nonetheless, the Spanish persisted, going to each village and demanding clothes for themselves. One member of the expedition later reported: “they [the puebloans] had to deliver….In this situation, they had no more time than to take off their outer fur robes and hand them over….The collectors gave mantas [blankets] and robes to some of the men-at-arms…who, if [the clothes] were not just so and they saw an Indian with another, better one, they exchanged with him without having greater respect and without ascertaining the rank of the ‘man’ they were despoiling.” Not surprisingly, the same expedition member subsequently reported, “[the Indians] were not a little angry over this.” Their anger led to a 50-day siege of the pueblos that the Spanish won at considerable cost. The cost to the Tigua was the loss of over 300 able-bodied men. In this initial, less than happy encounter, with the Spanish, the Tigua were described by Castaneda de Najera. In Castaneda’s descriptions, we begin to see the Tigua not just as the valiant fighters they proved themselves to be in their initial encounters with Coronado’s men, but also as a people with their own unique way of life: Tiguex is a provincia of 12 pueblos [on the] banks of a great and copiously flowing river, some pueblos on one side and others on the other [the Rio Grande]. It is a broad valley two leagues in width. To the east is a snow-covered mountain range, very high and rugged [the Sandia Mountains]….They erect their buildings communally. The women are in charge of making the mortar and putting up the walls. The men bring the wood and set it in place… The young men of marriageable age serve the pueblo as a whole. They bring the firewood that must be consumed, and they set it in a pile in the patios of the pueblo, from which the women take it to carry to their houses. The place of residence of the young men is in the estufas [kivas], which are underground in the patios of the pueblo. They [the kivas] are square or circular with pine pillars….The floors [were made[ of large, smooth stone slabs, as [in[ the baths which are the fashion in Europe. Inside, they have a fireplace [that looks] like a compass cabinet on a ship. There they light a handful of sage, with which they maintain the heat….. When anyone needs to marry it must be [done] in accordance with the rules of those who govern. The young man must spin yarn and weave a manta and lay it before the woman. If she covers [herself] with it, she is regarded as his wife. The houses belong to the women, the estufas to the men. If the young man spurns his wife, he must for that reason go to the estufa. It is an irreverent act for [a woman] to sleep in the estufa or to enter on any business other than to take food to her husband or her sons. The men spin and weave. The women raise the children and cook the food…. The pueblos are free of waste….They have houses that are excellently divided up, very clean, where they cook food and where they grind flour. The [grinding room] is a separate room or small secluded room where they have a large grinding bin with three stone set in mortar, where the women go, each one to her stone. One of them breaks the grain [corn], the next grinds [it], and the next one grinds [it] again. Before they go through the door, they remove their shoes and gather up their hair. They shake their clothes and cover they heads. While they grind, a man is seated at the door playing [music] with a flute. To the melody they draw their stones and sing in three parts. On a single occasion they grind a large quantity [of corn flour] because they make all their bread, like wafers, from flour mixed with hot water. All year they gather and dry a great quantity of small plants for cooking. In their land there are no fruits to eat except pinon nuts. Likely some of these details are partially or wholly erroneous because they were not based on a serious study of the Tigua and the two groups (Spanish and Tigua) did not speak each other’s language with any fluency. Yet, the details give a glimpse of Tigua life in 1540 that show a rich social life that continues to the present day. Tigua in El Paso after the Pueblo RevoltDespite Coronado’s disappointments in the land and the peoples he found there, Spain colonized New Mexico in the early 1600s, establishing ranches and a number of new cities including Santa Fe. South of modern Albuquerque were the Tigua and one of their prominent pueblos was known as La Isleta (pronounced the same as La Ysleta). For 80 years Spaniards and puebloans from Isleta, Taos, and other cities tried to find common ground. It was never an easy fit and accommodations were most often ceded to the Spanish who felt they “owned” the land and the people even though they themselves were recent arrivals. By August, 1680, things fell apart. Many of the northern pueblos united and, over a number of days, attacked the Spanish friars, haciendas, and towns. At first, Otermin, then the governor of New Mexico, defended his ground. Eventually, he retreated to El Paso. According to Andrew Knaut, who wrote the 1995 book The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 Conquest and Resistance in Seventeenth-Century New Mexico: "The causes of the revolt were many and the sufferings of the pueblos multiple. Within the Hispanic community, “disputes over land, labor, tribute, and rights of jurisdiction pitted governor against [clergy] during almost every administration between 1610 and 1670.” For the native peoples, Knaut notes “this divisiveness within the ranks of their European overlords…allowed members of the native community devoted to preserving Pueblo ways and beliefs to wage their campaign more openly.” Famines caused by recurring droughts coupled with European-induced diseases that were devastating to native groups, and the air was ripe for revolt in 1680. And, revolt they did in a united front that Otermin could not sweep aside. On August 23, 1680, Otermin, the Hispanic residents who were still alive, and native peoples who were not part of the revolt, fled south. Says Knaut: “The Pueblos…had accomplished what no other Amerindian society had achieved on such a scale before them, and what none would achieve after—a complete setback of European expansion in the New World.” While not overly fond of the Spanish, the Tigua, particularly those from Isleta Pueblo, did not join other pueblos in the revolt. Famine, their own failed revolt of the 1650s, and for their own reasons, the Tigua of Isleta pueblo chose not to participate. Instead some moved west to the Hopi pueblos; others south toward El Paso. The Spanish found the Tigua just north of El Paso. All those who abandoned central New Mexico—native peoples (Tigua, Piro, and others), soldiers, Otermin, Spanish citizens—settled in the El Paso area for what they hoped would be a temporary encampment. And for some it was. After a decade there, Don Diego de Vargas, who replaced Otermin as governor, “reconquered” New Mexico. Some Tigua returned to their native land in New Mexico at Isleta Pueblo where they reside today. But, some of the Tigua remained in the El Paso area, first near modern Juarez. Then in 1682, they founded Ysleta del Sur Pueblo in the vicinity of Fabens, Texas, but two years later in the vicinity of modern Ysleta, Texas, today a suburb of El Paso. At first life in the El Paso area was not easy. Governor Otermin, then in El Paso, wrote to the viceroy in Mexico that he had 2,000 souls, including the Tigua, who were starving and he did not have sufficient provisions for them. Most also feared reprisals from the native peoples to the north who were still in revolt. In the mid 1680s, the local Suma and some Manso Indians also revolted, causing yet more unrest. Slowly, however, life improved. A Catholic mission was established in Ysleta, one that today is represented by Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church located on their reservation in Ysleta. The initial settlement of Ysleta consisted of some buildings that may have resembled their multi-storied pueblo in New Mexico and built of adobe bricks. Other buildings were built in a different style. (See El Paso Missions to learn more about the Tigua in El Paso.) Today, the Tigua of Ysleta del Sur Pueblo are an integral part of the larger El Paso community and a tribe that is Federally Recognized by the U.S. government. Visitors to their pueblo will experience the church (always open and a place of quiet tranquility) and a bustling community that has become part of greater El Paso. Their patron saint is Saint Anthony (San Antonio) and still today on his saint day each spring, they hold a special festival beginning in the church and then going west to a point where for generations tribal members have spread out to knock on doors to collect alms (donations) for Saint Anthony. |

|