|

The archival research through which the history of Los Adaes is being written owes much to several generations of borderlands historians. Beginning in the early twentieth century, Herbert E. Bolton examined the Spanish colonization of North America in the shadow of his mentor, Frederick Jackson Turner, whose focus was the westward movement of the American frontier. Carlos E. Castaeda continued the Bolton tradition from the 1930s to the 1950s with his own massive seven-volume history of the Catholic Church heritage in Texas that focused upon the Franciscan missionary efforts to Christianize Indians.

The late 1960s and 1970s witnessed a new wave of borderlands historians from the "Bolton school," including Robert S. Weddle, John Francis Bannon (S.J.), Max L. Moorhead, John L. Kessell, Oakah L. Jones, Jr., David J. Weber, Felix D. Almaraz, Jr., and Donald E. Chipman. Collectively these scholars analyzed the trinity of Spanish institutions—military, missions, and towns—and the pioneers on the northern frontier of New Spain in greater depth.

Francis Galan's archival research on Los Adaes has benefited tremendously from this Bolton tradition as well as works of other scholars, particularly the analytical perspectives of Edward H. Spicer and Elizabeth A. H. John, and more recently Daniel H. Usner, Jr., Jesñs (Frank) de la Teja, Juliana Barr, and Helen Sophie Burton to name a few. The historian's research is complemented by the work of anthropologists and archeologists on the Caddos and their interactions with the French and Spanish, especially John R. Swanton, Pete Gregory, Timothy K. Perttula, and George Avery.

The Béxar Archives formed the core of Galan’s archival research on Los Adaes that began with two slave sales at Los Adaes in 1748 involving the governor of Spanish Texas. The Calendar to the Béxar Archives and Adan Benavides’ Name Index Guide to this archive were most helpful, as well as his guide to Spanish documents at the Mission Dolores Visitors Center in San Augustine, Texas. In addition, George Avery has compiled several very useful guides to archival documents related to Los Adaes that have appeared in the Annual Reports of the Los Adaes Station Archaeology Program.

Using these guides, Galan studied microfilm, photostat, and typescript copies of the original archives at various universities and depositories, including Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana, Stephen F. Austin University in Nacogdoches, Texas, the University of Texas at Austin, the Catholic Archives of Texas in Austin, Our Lady of the Lake University in San Antonio, and the University of Texas at San Antonio. These guides also enabled ready access for studying documents from the National Archives of Spain and Mexico. While there is no substitute for handling the original Spanish archives in a foreign country, the Béxar Archives at the Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin allows researchers to directly examine some of the most relevant original documents.

The hardest part of working with the archival documents is finding the time to sit alone and read through thousands of pages of original Castilian Spanish, and prioritizing which ones to translate that hold the most promise. While previous translations of certain Spanish and French documents are quite useful, the bulk of the existing documents of direct relevance to Los Adaes history have never been translated. Galan made many new translations of unstudied documents as well as some previously translated documents. Frank de la Teja edited many of Galan’s original translations.

The recent research into Los Adaes history has tapped into a very rich source of knowledge that to a large degree “confirms” the analysis of Elizabeth John and the important fieldwork of archeologists Pete Gregory and George Avery about the accommodation, or peaceful co-existence, among the Spaniards, French, and Caddos on the Louisiana-Texas borderlands. When Galan began his research, he was skeptical of this thesis because most historical secondary sources describe the Spanish conquest and colonization of Mexico and North America as everything but peaceful. But over the course of research he came to appreciate and agree with previous scholars—the story of Los Adaes is that of accommodation among three contrasting cultures thrown together by remote frontier circumstance.

The still untapped potential of archival research into the history of Los Adaes may yet prove more enlightening to the stories of the Louisiana-Texas borderlands, especially the negotiation of identity for native peoples and contraband trade. African-American history during the 18th century and early 19th century also remains to be examined closely, particularly enslaved Africans who fled slavery and settled in the Louisiana-Texas borderlands. Archeology, anthropology, and ethnohistory help fill the gaps in historical knowledge and challenge historians to “dig” even deeper for researching the interrelationships among diverse peoples and finding the relevancy of this past to the present.

Between and Beyond the Documentary Histories

One might ask, why do archeology if we have learned so much about Los Adaes from the documents? By studying material culture – the actual things people left behind – the archeologist discovers patterns and behaviors that the Spanish scribes and administrators never wrote about. In this regard, the archeological investigations at Los Adaes have turned up fascinating evidence of culture contact and illegal activity.

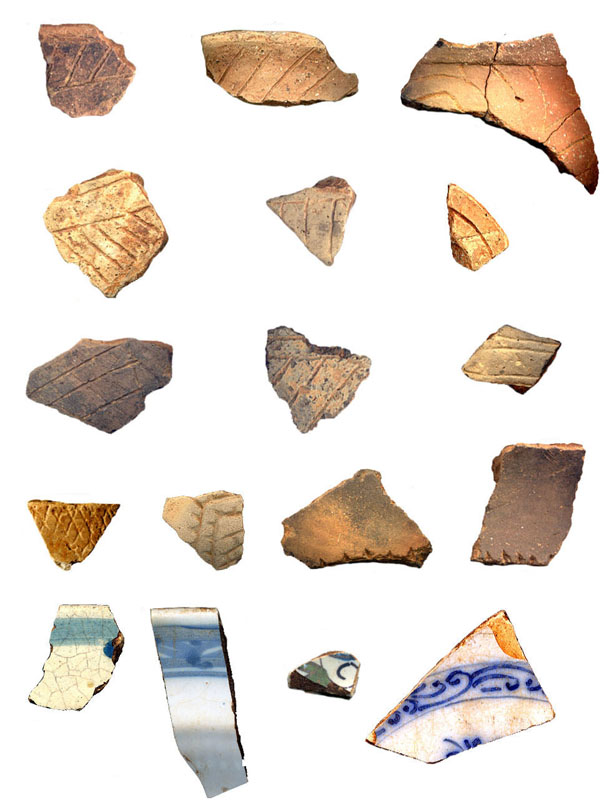

The native peoples (American Indians, Native Americans) in northwest Louisiana did not have a written language, and so their point of view is not represented in either the Spanish or French documents. We know from the documents that the Adai did not move their community to the mission built for them, but preferred instead to stay in their own settlements and simply visit the presidio when they chose to do so. Yet, at least eight out of every ten pottery sherds are from vessels made by Indians (the other sherds being European produced). These Indian sherds are from pots for cooking, storing, transporting, and serving food.

The pots used for storing and transporting food document close interaction between the Spanish and Indians, while the cooking pots suggest that some Indians, most likely women, may have been cooking for the soldiers of the presidio. Some Indian women almost certainly married into the presidio community, an inferred pattern that is largely invisible in the documentary record which is typically focused on the Spanish soldiers. Some of the Indian serving ware was made in the style of the European table ware—the Indian potters were essentially competing with (or mimicking) European potters by producing the brimmed bowls and pitchers which would have been present at the Spanish dinner table. There is virtually no mention of Indian pottery in any of the Spanish documents related to Los Adaes, yet Indian pottery dominates the ceramic assemblage from Los Adaes. This pattern must reflect both the difficulty of obtaining European pottery at the remote Spanish outpost as well as the otherwise poorly documented accommodation between the Spanish and the Adai and Caddo peoples.

Similarly, the presence of certain types of French merchandise at Los Adaes most likely reflects contraband trade, the details of which are rarely spelled out in the documents. It is certainly likely that much French cloth made its way to Los Adaes by legal channels, so the dominance of French lead cloth seals in the archeological finds might not necessarily represent illegal exchange. But the archeological recovery of French pottery and gunflints suggest a fairly active exchange between the Spanish and French. There are proportionately more French pottery sherds and French gunflints (than Spanish) at the presidios and missions closest to the French in Louisiana—the proportions of French pottery and gunflints diminishes markedly in the presidios and missions to the west. The one exception is Mission Dolores—the sister mission of Los Adaes—located in modern day San Augustine, Texas. The ratio of French to Spanish pottery is roughly one to one at Los Adaes, but is four to one at Mission Dolores. It appears that this form of illegal trade was not a constant thing at Los Adaes, but may have been a much more regular event at Mission Dolores.

For the 18th-century Spanish capital of Texas, history and archeology have proven to be complementary research avenues. Future researchers will have the opportunity to compare and contrast the implications of the archeological record of Los Adaes, reading between and beyond the documentary records to present a more balanced account.

|

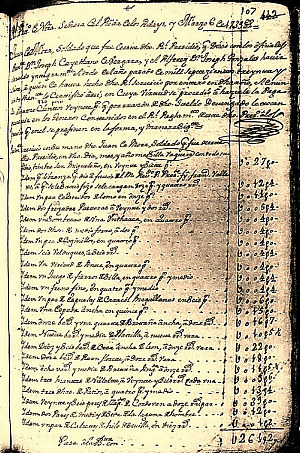

Account Book, March 6, 1739 at Presidio Los Adaes, example of Juan de Mora. Mora and the other troops who were often paid in goods in lieu of salaries . Goods included such items as soap, chocolate, sugar, clothing, sombreros (hats), threads, and other items. The significance of this account book and subsequent ones, according to historian Francis X. Galsÿn, is that it reveals the kinds of goods that were often purchased nearby at the French Natchitoches post if not supplied from New Spain, and, whenever the Adaesa os did not receive their salaries or necessary goods in a timely manner, contributed to the motivation for contraband trade with French traders and the Caddos.

Enlarge image to see details.  |

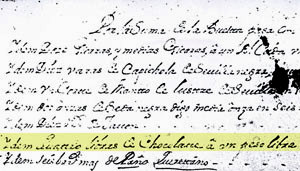

Account book entries, Lt. don Joseph Gonzales. Highlighted line: 4 libras (pounds) of chocolate. |

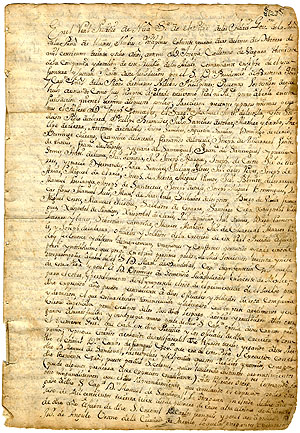

Power of Attorney, January 24, 1738 at Presidio Los Adaes, the officers and soldiers of Los Adaes appeared before Lt. General don Joseph Cayetano de Bergara, to annul a power of attorney given to former Governor Manuel Sandoval for the collection of their salaries. The troops transferred their power of attorney to Sandoval's successor, don Carlos Franquis de Lugo, while he was interim governor of Texas. The officers and soldiers then gave power of attorney to Governor Orobio y Bazterra, who followed Lugo, while don Domingo Gomendio remained as the secondary party in Mexico City to request payment of Adaesa o salaries from the Royal Treasury. Source: Béxar Archives, Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin (Box 2S26).  |

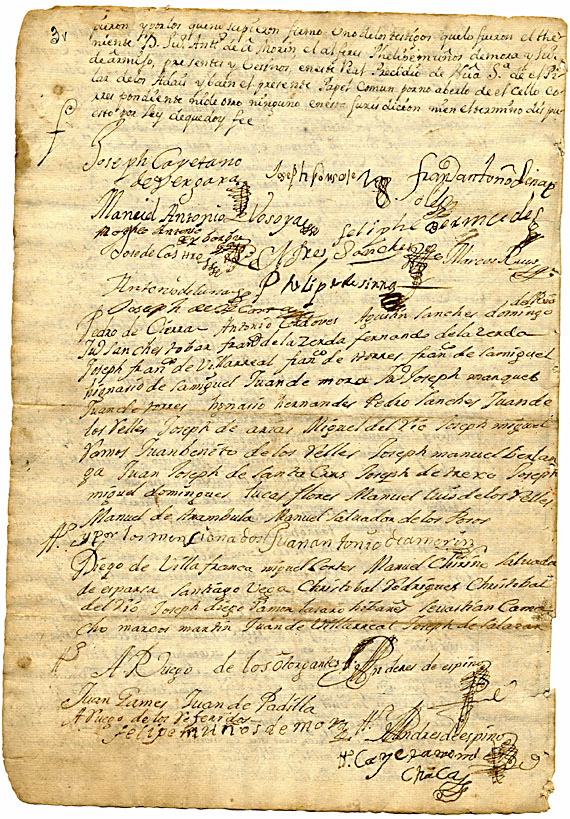

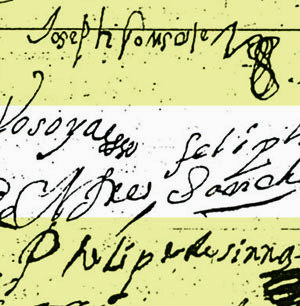

Signature page, Power of Attorney, January 24, 1738 at Presidio Los Adaes, those officers and soldiers who knew how to write their own names signed the document, for example, Lt. Joseph Gonzales, Mateo Ybarbo, Philipe de Sierra, Joseph de Acosta, Felipe Bermudes and Marocs Ruiz. Those who were illiterate, including Juan de Mora, Manuel Chirino, Antonio Cordoves, Domingo del Rio, Francisco de la Cerda and many more, had testigos (witnesses) sign for them. According to historian Francis X. Galsÿn, such power of attorney and many subsequent ones became sources for abuse of the Adaesa o troops. Source: Béxar Archives,Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin (Box 2S26).  |

Highlighted signatures of Lt. Joseph Gonzales and Philipe de Sierra from Power of Attorney document. |

At least eight out of every ten pottery sherds archeologists have recovered from Los Adaes are from vessels made by Indians, the other sherds being European produced. This skewed ratio can be partially explained by the facts that ative pottery was low-fired and more easily broken, while the harder-to-come-by imported pottery would have been handled more carefully. Still, the high proportion of native pottery must reflect both the difficulty of obtaining European pottery at the remote Spanish outpost as well as the otherwise poorly documented accommodation between the Spanish and the Adai and Caddo peoples.  |

|