Cultural Worlds

|

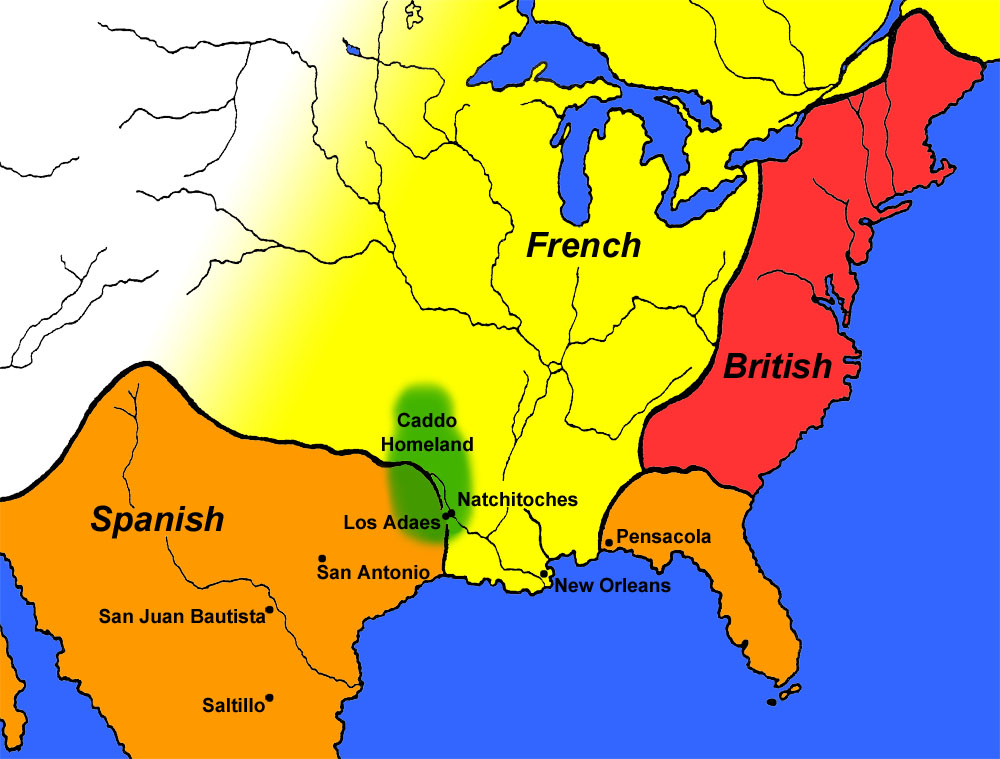

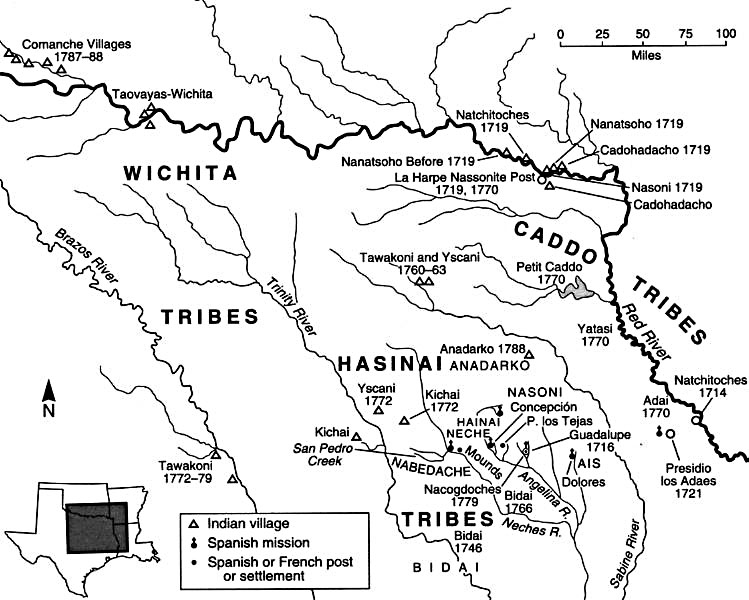

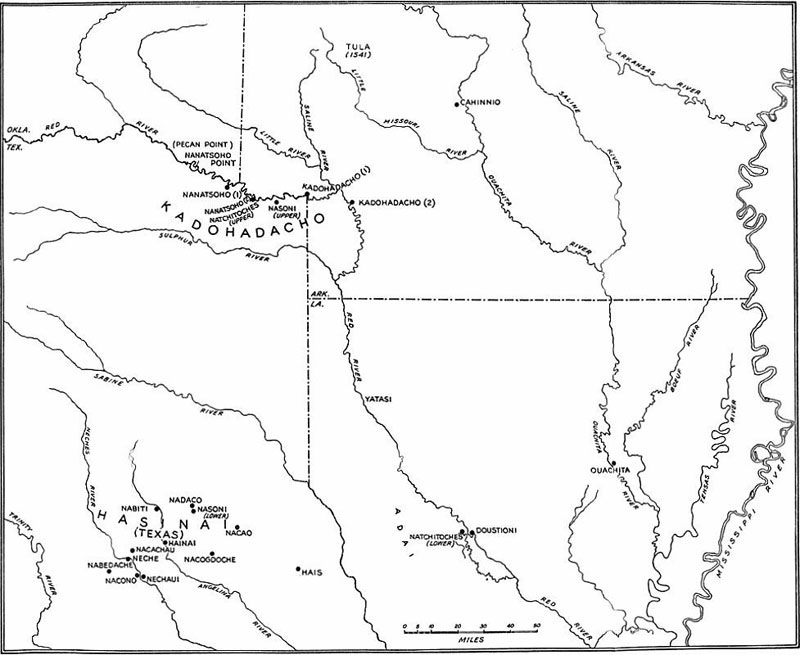

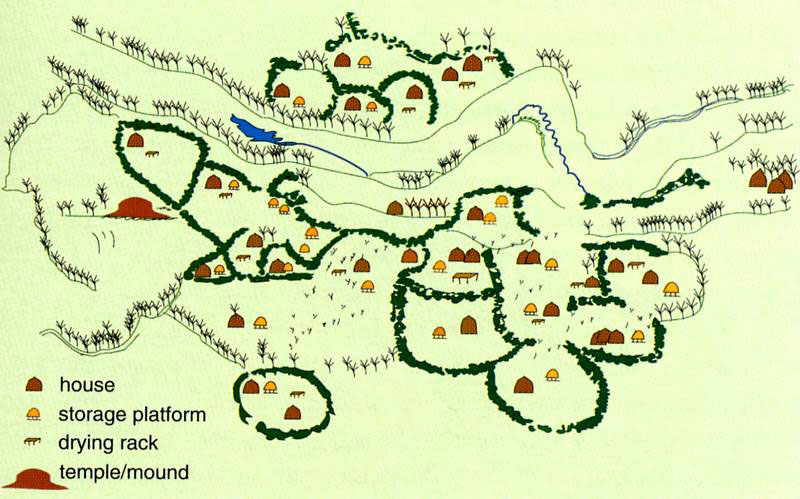

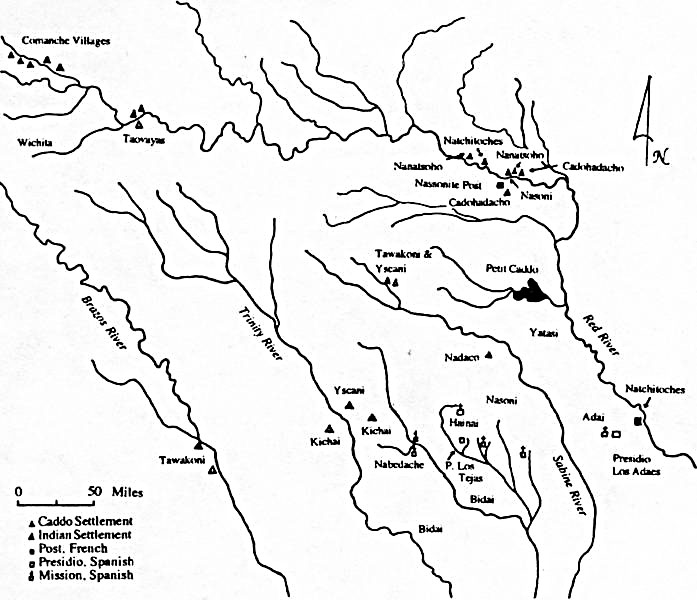

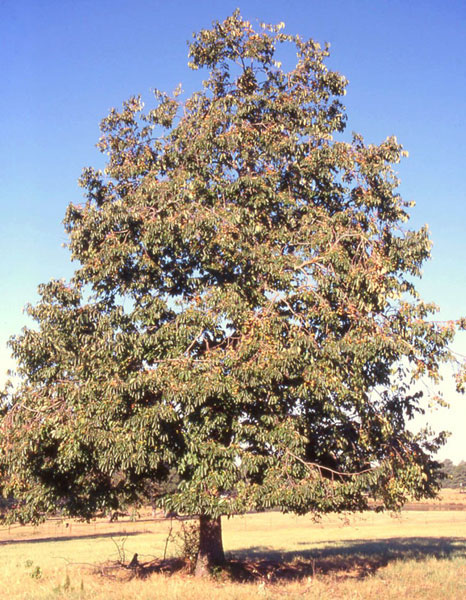

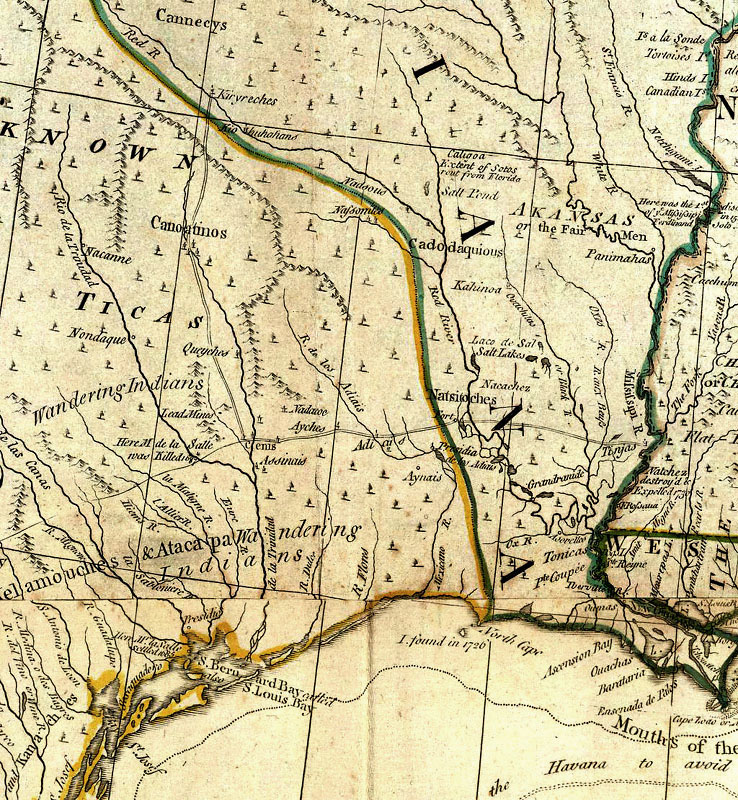

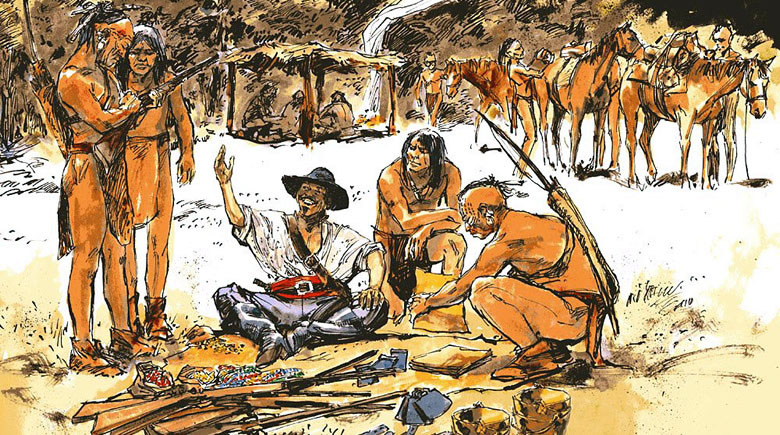

The story of Los Adaes cannot be understood without an appreciation of the three overlapping cultural worlds that shaped its history: that of the region's native peoples, the Spanish, and the French. In the late 17th century when Spanish and French laid claim to the pine-forested region in what is today eastern Texas and northwestern Louisiana they were claiming more than territory, they were also claiming sovereignty over the native peoples whose ancestors had lived there for generations upon generations. Within the pineywoods region of eastern Texas and adjacent northwestern Louisiana were dozens of groups of Indians (Native Americans) often called "tribes" or "nations," each made up of many smaller groupings that could be termed "communities." Among these groups were peoples speaking differing languages and dialects who lived in recognized territories that they sometimes shared and sometimes defended quite fiercely. Collectively, most of the region's peoples shared similar ways of life - they were farmers, hunters, gatherers, and fisher folk, as well as pottery makers, warriors, healers, and traders. They lived in villages and hamlets, most of which were situated on the forest edges large and small, where the thick woods gave way to streams, rivers, prairies, lakes, and cleared fields. It was a settled world that the Spanish found quite civilized compared to the small mobile groups of "savage" hunters and gatherers they encountered across coastal and southern Texas and the mounted raiders from the northwest. Neatly and accurately describing the native world as it existed at the outset of 18th century is quite impossible, too much has been lost forever. Most of the oral tradition through which native histories were handed down generation to generation did not survive. Neither did most groups. The relatively few tribes in the region that did survive, such as today's Caddo Nation, are the descendants of what were once many distinct groups, related by shared languages and tradition, but thrown together by history. By 1700 Native America was already in flux as the impacts of Old World peoples spread far in advance of sustained European settlement. The European intruders, and the living and manufactured things they brought with them, quickly transformed the native world in unprecedented, devastating ways. Old World diseases, horses, and guns had the most immediate impacts, but the clash of two worlds foreign to one another would ultimately result in the destruction of the existing native societies. The best clues about the 18th century native world come from the documentary records left by the Europeans, but the soldiers, priests, and colonial government officials who authored expedition diaries, inspection reports, and legal briefs - saw native peoples through distorted lenses colored by their own prejudices, desires and world views. They tried to describe and explain the strange peoples who they encountered, often to justify their own actions to their superiors in the heartland of New Spain (central Mexico) and in distant Europe. The lands and peoples they wrote about were part of a complex cultural and physical landscape that was only partially and poorly charted. Scribes writing decades apart gave many different names to groups and landforms. Therefore, searching 18th century Spanish and French documents for information about the Indian peoples of the eastern frontier of New Spain requires great diligence and special skill for reading between the lines. Caddo WorldLos Adaes is situated in the southern part of the cultural area that archeologists and anthropologists often call the Caddoan Area. On this website we prefer to use a more evocative term, the Caddo Homeland, to characterize the region which was home to perhaps 150 generations of peoples who spoke Caddo language or one of its dialects or ancestral forms (see Caddo Fundamentals). The main Caddo Homeland stretched for about 300 miles (480 kilometers) north-south and 220 miles (355 kilometers) east-west, a vast territory of about 51,830 square miles (134,235) square kilometers. Today's Caddo are the descendants of many distinct communities of people who shared, in part, a common culture. In the late 1600s and early 1700s, Spanish and French chroniclers familiar with the Caddo Homeland recorded the names of at least 25 separate groups who spoke dialects of the language known today as Caddo. Beyond speaking the same basic language, these groups were linked by many shared customs, a similar way of life, and by intermarriage. All were settled farming peoples who, when first encountered by Europeans, still lived in traditional communities, scattered and stretched out along river and stream valleys in farmsteads, hamlets and villages of various sizes. Their most important religious and political leaders usually lived in or near the larger and older villages. Such places were ritual centers where towering temples built of poles and grass thatch stood, often atop earthen mounds. At sacred and festive times such as First Harvest and in times of crisis, the scattered Caddo gathered where their society's leaders lived. Because of population loss and enemy encroachment triggered by the intrusion of Europeans in the late 17th century, most Caddo groups eventually organized themselves into the Hasinai, Cadohadacho (also spelled Kadohadacho), and Natchitoches alliances (often misleadingly called "confederacies" a term which implies a more formal and lasting union than was the case). Group consolidation took place in the Neches and Angelina river valleys in east Texas (the Hasinai), the Great Bend area of the Red River (the Cadohadacho), and in the vicinity of the French post of Natchitoches, Louisiana. Of these alliances, the Cadohadacho and Hasinai were the main groups who led the largest and most influential alliances encountered by the Spanish and French. The Hasinai groups, the westernmost Caddo-speaking peoples were first known to the Spanish as the "great Kingdom of the Tejas," a name subsequently appropriated for the 18th century Spanish province and the modern state of Texas. The Cadohadacho lived further to the east along what appears to have been the true heartland of the Caddo world - the Great Bend of the Red River. The Hasinai and Cadohadacho groups were also the major trading partners of the French and, to a far lesser extent, of the Spanish. The Natchitoches alliance was much smaller and is not well known. Its subdivisions were said by John Swanton to consist of the Natchitoches and the Doustioni, who were joined by some members of the Ouachita and the Yatsi tribes. During the 18th century the Natchitoches were allied with, and lived around, the French at the trade center named after the tribe. On the edges of the Caddo Homeland, particularly to the northwest in what is today Oklahoma and the south in what is today southeastern Texas and adjacent Louisiana, were other peoples who did not speak a Caddo dialect as their native tongue. But many of these probably did speak related languages that linguists classify as belonging to the Caddoan language family, which includes relatively well known groups such as the Pawnee and Arikara whose ancestors had migrated far out on the Great Plains, as well as the Wichita and the Kitsai who lived in parts of Oklahoma and northern Texas in the 18th century. In the southern periphery of the Caddo Homeland were also smaller groups that may have spoken Caddoan languages, but were considered separate, less influential peoples by the more powerful groups that spoke Caddo dialects. Among these were the Adais, the Ais, and the Bidais, and of these we'll discuss only the Adais. Adai IndiansThe Adais (or Adai), for whom Los Adaes was named, were a relatively small group whose traditional territory was west of the Red River and east of the Sabine River. In historic records their name is variously spelled Adais, Adai, Adaes, Adayes, Atais, Nadas, and possibly, Atayos and Haqui. Their name could be derived from the Caddo words Na dai, meaning "A Place along a Stream." Anthropologists and historians have often referred to, and classified the Adais as a Caddo or Caddoan group, but their linguistic and cultural relationships to other Caddoan language family groups remains poorly understood. As the famous Indian agent John Sibley said about the Adais in 1805, "their language differs from all other, and is so difficult to speak, or understand, that no other nation can speak ten words of it, but they all speak Caddo" (quoted in Swanton 1942). Modern linguists still aren't sure whether their language was a true isolate, meaning was not closely related to any known language, or a divergent Caddoan language. Regardless, the Adais had their own language and their own distinct identity. Yet they lived quite close to, interacted with, and shared cultural similarities to some of the groups speaking dialects of the Caddo language (such as the Natchitoches). Several early European travelers through Texas prior to the 1790s may have encountered the Adais, based on somewhat similar sounding tribal names (homologues). The first was the Spanish shipwreck survivor Cabeza de Vaca, who encountered a group he called the Atayos in 1528-1530 along the central Texas coast. Over a century and a half later a group called the Haqui were seen in the Sabine or Sulphur River valleys in 1687 by the Frenchman Henri Joutel, a survivor of the failed La Salle expedition. These ambiguous passing references shed little light on the early history of the Adais. In the late 17th and early 18th century when the Adais became well known to the French and Spanish, they lived in the area west of the Red River and east of the Sabine River in what is today northwestern Louisiana. Their traditional territory can be affixed by the founding of Mission San Miguel de Linares de los Adaes in 1717 near present day Robeline, Louisiana. Although the Spanish mission was dedicated to and named for the Adais, who the Spanish considered close allies, most of the early information describing the tribe comes from the French, with whom they were also allied. In the late 17th century and the early 18th century French reports from Henri de Tonti, Pierre Le Moine d'Iberville, Bienville, and St. Denis placed the Adais about 18 miles west of the Red River in several villages with about 50 warriors or, conservatively, settlements of about 200 people. These and other historical reports show the Adais practiced horticulture, gathered wild fruits and roots, hunted a variety of large and small mammals, and made extensive use of lacustrine (lake side) resources. They harvested tubers and persimmon fruits. The French also reported that the Adais lived off the hunt, and made baskets and nets that they sold or exchanged at Natchitoches. The account of the French explorer and trader, BZ¿nard de La Harpe, provides a particularly interesting view of Adais culture and traditions. On November 21, 1720, while returning from a trip up the Red River to Cadohadacho territory, La Harpe got feverishly sick. Ill and short of food, he sent scouts to a village of the Adais to obtain food for his party. On December 4, a party of 53 Adais accompanied by their chief reached the French and found La Harpe unconscious, very swollen and near death. Seeing La Harpe's condition, the Adais sent for three of their shamans (healers) who used several curing practices to give him relief, transported him downriver, and saved his life. In the fall of 1721, the Marqués de Aguayo returned to the abandoned site of the first Mission Los Adaes. Aguayo's scouts located Adais rancherias 10 to 12 leagues (25-30 miles) to the north of the old mission site, where they were living along the shore of a large lake. Aguayo proceeded to re-establish the mission and build a presidio a few miles east of the old location, some seven leagues (18 miles) from Natchitoches. The Spanish commented on the Lake of the Adais (Laguna de Los Adaes) and on the abundance of resources in the Adais country such as fish, great variety of ducks, bear, deer, walnuts and "medlars" (persimmons). Like La Harpe, the diarist commented that the Adais made medlar cakes, which they stored as winter food as well as supplies of bear fat. After re-establishing the mission and establishing the presidio Aguayo was visited by the chief of the Adais, who was accompanied by about 400 of his people. To generalize, the early 18th century Adais at the onset of the Spanish and French settlement seem to have followed a lifestyle similar to that of Caddo-speaking groups and other settled peoples of the Southeastern U.S. They lived in hamlets and villages near bodies of water. They grew corn, beans, and tobacco but had a diverse economy in which hunting, gathering, and fishing all played important roles. By comparison to the main Caddo groups, the Adai were a less numerous people that did not have large villages and the more hierarchical social and religious organization characteristic of the Hasinai and the Cadohadacho. So far no definitive Adais archeological sites have been excavated, although several candidates have been mentioned, including a cemetery presumably associated with a village site, at Allen Plantation on the north side of Spanish Lake. There in 1936 James A. Ford, one of the leading American archeologists of the day, reportedly excavated burials with European trade goods. Unfortunately, the results of this work were never published. The exact relationships among the Adais, the Spanish and French during the Los Adaes years are difficult to sort out and separate from interactions with other Indian groups, especially the various Caddo groups who were the main trading partners of the French at Natchitoches. The Aguayo expedition brought to Los Adaes large numbers of sheep and cattle in 1721 and ranching and raising livestock became the most successful Spanish enterprise. It is likely that the Adais helped the Spanish establish ranches around Los Adaes, introducing the Adais to animal husbandry. Later Spanish reports by friars and the military show that the Adais maintained close ties with the French through trade. This trade included large numbers of horses, hides, chamois, corn, beads, vermillion and weaponry, and it is likely that the Adais served as middlemen for trade between the French and the Spanish, and the Caddo-speaking peoples to the west and to the north. Several of the major land trails and water routes used to smuggle contraband through Spanish territory, such as Bayou Pierre, passed through the traditional Adai homeland. According to eyewitness Spanish inspection accounts in 1727 and 1768, the Adai never congregated at Mission Los Adaes, probably because they preferred to live in villages along major streams and around the Laguna de los Adais (latter known as Spanish Lake) where they had ready access to their traditional foods. None of the Spanish missions in the eastern province of Texas succeeded in attracting resident Indian populations. After the mission and presidio were closed in 1773, some Adais moved to San Antonio where they were housed at Mission San Antonio de Valero while others remained in their homeland or later return to it. In 1778 Athanase de MeziZ¿r?s, a Frenchman appointed by the Spanish as the lieutenant governor of Natchitoches, wanted to secure native warriors for a campaign against the Apache. His report indicates that the Adais and other local tribes had suffered great losses due to a smallpox epidemic that had also killed two of de MeziZ¿r?s family members. Clearly, the Adaes suffered major population loss in the late 18th and early 19th centuries as did so many other North American tribes. One of the last historic estimates of Adais population was provided by Henry Schoolcraft, whose informant gave the population of the Adais as 27. Although the Adais tribe did not survive the 19th century as a separate nation, their heritage lives on in and beyond the Adai traditional territory. During the 18th century they intermixed with Spanish, French, and other Indian peoples. By the early 19th century calling attention to one's Indian heritage was not socially accepted in northwestern Louisiana, like much of the United States. In contrast, Spanish and French heritage was heralded and traceable by the survival of Spanish and French surnames. Among those who stayed in the Los Adaes settlement area, the Spanish identity was considered especially important, and quite distinct from Mexican heritage. Today attitudes toward Indian heritage have changed and many Adaeseños recognize and proclaim their Adais heritage. Recognized by the State of Louisiana as the Adai Caddo Indian Nation, the tribe has established a museum and visitor center approximately 5 miles north of Los Adais State Historic Site. Spanish Texas and French LouisianaDuring the later decades of the 17th Century the Spanish and French vied for control of much of the area today known as Texas. The Spanish were spreading northward and northeastward from the core area of New Spain (today's Mexico) while the French were spreading southward down the Mississippi River and westward across all the lands drained by it, which they called La Louisiane. The boundary between the Spanish province of Tejas and the French colony of Lower Louisiana was not well-defined and both European empires claimed far more land than they actually controlled. The frontier area that today falls within the eastern part of Texas and the northwestern part of Louisiana was largely terra incognita, a fact reflected by the quite inaccurate maps of the day (see 18th Century Maps). New Spain was a source of great wealth for the Spanish Crown. The gold and silver from mines in what is today central and north-central Mexico had financed Spain's rise to power and world domination in the 16th and 17th centuries. The French Crown coveted the silver and gold produced in New Spain and sought to find ways to tap into this wealth, chiefly through trade and the development of a mercantile economy. Although the two European powers would become allies throughout much of the 18th century during the Bourbon dynasty, their colonial histories and practices were very different. The Spanish Empire in the New World was expanded and controlled by military forces, religious institutions, and civil administrations, embodied by the presidio (royal fort), the mission (mission), and the pueblo (town), the most important of which were linked by overland travel corridors called camino reales (royal roads). New Spain was ruled by the Spanish Crown through its appointed viceroy based in Mexico City, under whom the provincial governors administered Spanish law. Military forces were used to defend the population centers and the outlying frontier outposts, which were often established as paired presidios and missions, as was the case of Los Adaes. The Spanish sought to gain control over the native peoples of the New World by aggressively converting them to Christianity and congregating, often by force, native populations around the missions and pueblos. The missionaries were members of the Jesuit and Franciscan religious orders of the Roman Catholic Church; the mission at Los Adaes was under the Franciscan order (there were no Jesuits in Texas). The French colonies had a roughly analogous colonial system, but it was less regimented with a much weaker religious component and much greater emphasis on trade and kinship, rather than conquest and conversion. Because France claimed much of eastern North America, the French came into conflict with the British in North America earlier than the Spanish (except in Florida). By the time Lower Louisiana was settled in the early 18th century, the French had long experience building trading alliances with Indian peoples, most notably through the fur trade. And the French freely intermarried, or otherwise established kinship ties with native peoples, a practice often discouraged or even officially prohibited by the Spanish. Much of the tension between the Spanish and French in the 18th century New World had an economic basis. Spain was unable to produce all the merchandise required by its growing New World colonies. To meet this need, the Spanish Crown bought manufactured goods from France and other European countries and shipped these to the New World to be sold at a sizeable profit. In order to maximize the profit, the Spanish Crown would not allow the French to trade directly with the Spanish Colonies. In contrast, the French Crown allowed and encouraged trade, but exacted considerable taxes and fees from those French citizens to whom they issued trading licenses. The European royal aspirations to control the wealth of New Spain and Louisiana were often thwarted by the personal ambitions and actions of French and Spanish citizens in the New World. These colonists and adventurers sought to amass their own wealth through landownership, mercantile activities, and earning royal favor through military and political service to the kings. The Spanish citizens were defined by a casta system that ranked aristocrats born in Spain at the top of a racial hierarchy that had Native Americans and slaves at the bottom, with those born of mixed ancestry and New World colonial heritage somewhere in between. One's racial classification (casta) greatly constrained social position, career advancement, and wealth. Although French-born aristocracy had similar notions, the French citizens of Louisiana were much less constrained by racial classification and, as a consequence, their society was less stratified and somewhat more open. That said, the 18th century French practiced slavery to a far greater extent than did the Spanish, who officially prohibited the practice. Conflict between the Spanish and French first arose in the eastern part of Texas in 1684 when the Frenchman La Salle established Fort St Louis on Matagorda Bay in what is today the Coastal Bend of Texas. As is now well known, La Salle's intent to establish a colony was unsuccessful in part due to the wreck of his flagship, La Belle, and succeeding struggles. Fort St Louis was destroyed in 1688, by internal dissent, disease, and Indian attack. But the French incursion into frontier lands claimed by Spain provoked repeated attempts by the Spanish to find and rid themselves of the perceived French threat. The military and political ambitions of the Spanish in eastern Texas were paralleled by the religious ambitions of missionaries - converting and congregating Indian groups, especially the friendly settled agricultural groups that collectively have come to be known as the Caddo. In 1690 two missions were established among Hasinai Caddo groups known to the Spanish as the Tejas in what is today northeastern Texas. These failed to attract converts and were soon abandoned, in part because they were too remote to be effectively supplied by the Spanish, but in large part because the Hasinai and other Caddo groups had a centuries-old successful way of life with extensive settlements and their own religious and military authorities. The Caddo were friendly and desired European goods, but were not interested in becoming Christians and they were not at all happy with the way that the Spanish soldiers who accompanied the missionaries behaved. Meanwhile, the French began to develop trade connections with Caddo groups in the late 17th Century (1600s), offering guns, ammunition, metal goods, beads, and other European goods in exchange for deer skins, horses, bear grease, and Indian slaves. Throughout the 18th Century this trade-based economic approach proved much more successful than the Spanish attempts to dominate and conquer through force and conversion. In the early 1700s the French established forts and trading centers in Louisiana and formed close relations with the Natchitoches Indians, a Caddo-speaking group that lived along the lower and middle Red River. They also attempted to establish commercial relations with New Spain by sending a ship with trade goods to Veracruz, an effort that was rejected by the Spanish authorities. This rebuff did not stop the mingling of the French and Spanish worlds. It was on the overlapping frontier of these three cultural worlds, Spanish, French, and Caddo, that Los Adaes was established in 1721, its purpose to defend New Spain and the province of Texas from the ambitions of the French, and to convert and subjugate Caddo peoples. |

|