|

Los Adaes may have been abandoned in 1773, but the cultural heritage of the 18th-century Spanish capital of Texas lives on. Much like ripples expanding outward from a rock tossed into a still pond, Adaeseo cultural traces have become fainter and fainter as at least eight generations have come and gone. Yet recent decades have seen renewed interest in the Adaeseo cultural legacy as well as in the physical traces represented by Los Adaes as an archeological site. The establishment of the Los Adaes State Historic Site by the state of Louisiana in 1979 has served as an essential focal point for both cultural awakening and for the preservation of the fragile site itself.

Here we attempt to trace the Los Adaes ripples as they have made themselves known in history, language, and culture. We conclude with speculations and our hopes for what the future might hold for the 18th-century capital of Spanish Texas.

Adaeseos in the Late 18th and Early 19th Centuries

The Adaeseos' resettlement troubles at Bucareli and Nacogdoches coincided with tumultuous events elsewhere in North America and Europe. The period coincided with the American Revolution. Spain declared war in 1779 against Britain in alliance with Bourbon France and rebellious American patriots. During the late 1770s, seemingly far away from the troubles at Bucareli and Nacogdoches, Spanish Bourbon officials sent dispatches to all its officers in the Americas, including the viceroys, governors, and other government officials, about guarding against illicit trade. At the local level, however, the final re-settlement of former Adaeseos at Nacogdoches in the winter and spring of 1779 deeper into East Texas made this familiar place an important center for contraband trade. Fleeing the Comanches from the west, Ybarbo and other former Adaeseos became ever more entwined with French, British, and American traders as revolutionary events, creation of the United States, and the Louisiana Purchase increasingly impinged upon the Louisiana-Texas borderlands.

While Governor Cabello delicately balanced the complaints of secular and religious officials at San Antonio de BZ¿xar amidst Indian raids, another daunting task involved weighing local economic interests of settlers in Spanish Texas versus the King's mercantile policies against free trade. The accommodation of the Spanish, French, and Caddos on the Louisiana-Texas borderlands predicated upon commercial and social networks left descendants of the original Adaeseo pioneers at Nacogdoches and vicinity to face similar challenges from larger political developments and migrations of other Indian nations and settlers from the United States, Canada, and Europe.

Although Bucareli succumbed to flooding of the lower Trinity River and Comanche raids, the new town of Nacogdoches persevered. Its protection came from Ybarbo's militia, composed of former Adaeseos, and the Tejas Caddos under Chief El Texito. Governor Cabello's peace treaty with the Comanche nation at San Antonio de BZ¿xar by 1785 also helped restore the relative tranquility that former Adaeseos had enjoyed over the years on the Louisiana-Texas borderlands. Ybarbo's fortitude and commitment to the survival of Nacogdoches carried with it memories of youthful adventure, romance, hardship, and sorrow shared by Adaeseo pioneers along with their French and Caddo neighbors.

For those Adaeseos who remained at San Antonio de BZ¿xar, they finally received land following the secularization of Mission San Antonio de Valero (present-day "Alamo") in 1793. According to historian Jesñs (Frank) de la Teja, 45 Adaeseos evidently received the largest parcels. The remaining Adaeseos at San Antonio de BZ¿xar continued military service at its presidio, while the others presumably entered the civilian community at the Villa of San Fernando, which Canary Islanders established in 1731.

One former Adaeseo in particular, Manuel Berbsÿn [Derbanne], apparently had already moved to San Antonio de BZ¿xar with his parents: Victoria Gonzales-Derbanne, daughter of Lt. Joseph Gonzales, who was a forty-year veteran from Los Adaes, and Jean Baptiste Derbanne, soldier, and son of Fran?ois Derbanne, an early pioneer of French Natchitoches with St. Denis. Manuel Berban, who had served with his father and grandfather at Presidio Los Adaes, years later sat on the cabildo at San Antonio de BZ¿xar in 1796 as councilman and then as attorney in 1801. A smaller number of Adaeseos continued their military service at Presidio La Bah?a (present Goliad), most notably Juan Chirino, who was called into duty at San Antonio de BZ¿xar from Los Adaes in 1771 to fight against Southern Plains Indians.

Many of the Adaeseos who stayed behind on the Louisiana-Texas borderlands eventually reunited with family at Bucareli, Nacogdoches, or their ranches. Some were able to stake land claims in northwestern Louisiana. For instance, there is the somewhat curious case of Louis Procello, son of Pedro Procello a Spanish soldier who had been stationed at Los Adaes in its waning years. According to Natchitoches Parish records, Louis Procello was born at "Los Adaes" in 1778, five years after the Spanish post was abandoned. The birth place name probably refers to a small community formed by Adaeseños who never left the area. Sometime before 1819, Procello became the recognized owner of a section of land in De Soto Parish, some 25 miles north of Los Adaes. The family name Prosel (sometimes spelled Procel or Procelle) is still common in northwestern Louisiana today and presumably represents decendants of Louis Procello or his brother Manuel.

Still other Adaeseos joined rural communities that emerged on both sides of the Sabine River, which became the state boundary line between Louisiana and Texas decades later. The small community of Chireno, located halfway between Nacogdoches and San Augustine, was named after Jose Antonio Chireno, a descendant of the Chirino family from Presidio Los Adaes. The Spanish Lake community formed just north of the abandoned Los Adaes fort. Former Adaeseos and their descendants continued sharing in the celebration of church sacraments at Natchitoches beyond the Louisiana Purchase.

Along with Béxareos (residents of San Antonio de BZ¿xar), the Adaeseo descendants appeared at Natchitoches with divided loyalties to organize revolutionary movements against Spain and Mexico with Anglo-Americans, especially the Gutierrez-Magee expedition (1812-1813) and the Texas Revolution (1835-1836). The CÜrdova Revolt (1838) against the Republic of Texas, named after its principal leader, had ancestors from Los Adaes. The Nacogdoches and San Antonio de BZ¿xar settlements emerged as centers of revolutionary developments in Texas with the aid of Natchitoches and New Orleans as the northward expansion of New Spain and the westward expansion of the United States collided for the first time in the Pineywoods of the Louisiana-Texas borderlands in the early 19th century.

Los Adaes-Related Indian Peoples

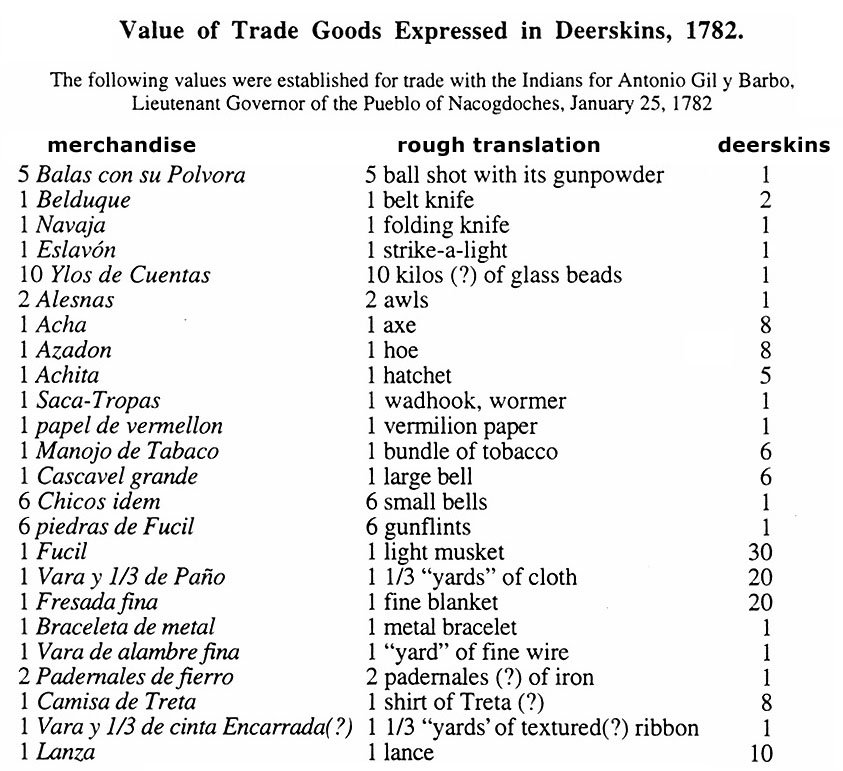

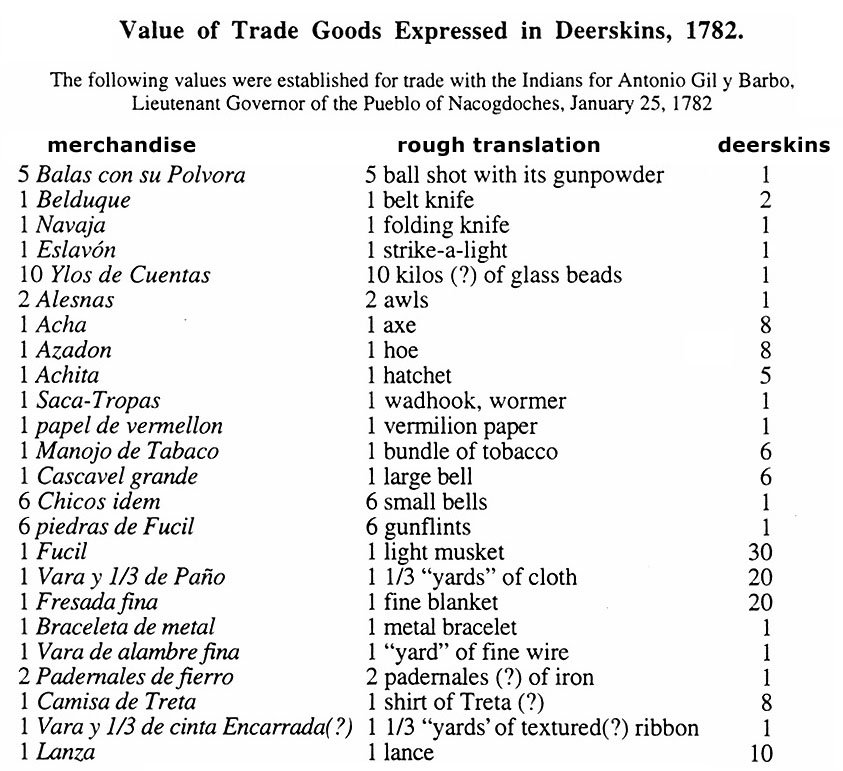

The Caddos survived in their ancestral homelands long after the abandonment of Presidio Los Adaes, but in smaller numbers and more dependent upon European trade than ever before. Spanish officials sought their allegiance through traditional gift-giving which the Spaniards and French competed for previously. By the 1780s, following haphazard and ineffective Spanish-Indian policies, Spanish officials still sought to win influence over the Caddo and Nations of the North through gift-giving, especially weapons, clothing, tobacco, and farm tools that arrived from New Orleans. In 1785, Spanish officials estimated 394 Tejas, 238 Nacogdoches and Nazones, and 309 Bidais Indians had received various amounts of muskets, gunpowder, ammunition, farming hoes, axes, knives, chain links, bells, tobacco, skirts, and other products.

Spanish officials also listed the Adaes, Ais, and Saisitos Indians together, who numbered 213 people and received similar goods as did the Caddo nations. The Adaes Indians did not have a captain whom the Spaniards presented with gifts, but instead received goods through the Ais captain. The Adai Indian Nation still exists today in the area of the abandoned fort and mission. Near by is the present Ebarb community, with descendants from Los Adaes. The Caddo Nation proper, however, is based in Oklahoma today after their own exodus from ancestral lands in the early nineteenth century followed the same challenges that other Indian nations and Adaeseo descendants encountered on the Louisiana-Texas borderlands. (To learn more see Caddo Voices: Past and Present).

Caddo and Adai peoples were not the only Indians who were associated with Los Adaes. By the 18th century an active American Indian slave trade had developed in lower Louisiana. The French were enslaving Indian people from tribes that opposed the French and their Indian allies, such as the Caddo. Chitimacha and Natchez slaves were held at Natchitoches in the 1730s, a consequence of their wars with the French and the active French traffic in Indian slaves. Although Spanish authorities forbade Indian slavery, it spread across the northern frontier as their tribal allies traded captives to the French. By the middle 18th century Apache slaves, especially Lipan Apache, were being obtained by the French as part of their trade with the Norteños on Red River, adding those enemies of Spain to the mix of French-enslaved tribal peoples.

During the middle to late 1700s, Lipan Apache slaves and former slaves became part of the greater Los Adaes-Nachitoches community. These people, termed the Connechi or Canchy, were freed as were all the Native Indian slaves when Spain acquired Louisiana. The American agent, Dr. John Sibley, noted in 1803 that they were different and that they had mixed with the Europeans. The dominant tribal intermarriages seem to have been the result of the slave trade, although the Caddo and Yatasi also intermarried with French and Spanish neighbors. Most American Indian slaves seem to have been women and children most of whom were baptized and raised in the European communities. By the time Nacogdoches was founded in 1779, the Connechi were present among the Adaeseos moving about the Louisiana-Texas frontier.

After the Spanish acquisition of Louisiana , the impact of the deerskin trade on tribal economies to the east of the Mississippi River led many of those groups to move west. The most populous of the Southeastern groups moving west were Choctaw and some Chickasaw Indians who hunted on the Red River and into the Sabine drainage. The Caddo objected to these intrusions and threatened war, but the Choctaw persisted in crossing the Mississippi. Spanish authority did little other than try diplomacy to maintain detente between the tribes. By 1803-1805 these Choctaw had a strong enough presence that the Americans attempted to establish a polity for them, having them come to Natchitoches to elect a chief.

Groups of Choctaw roamed the region well into the early twentieth century and these small bands contributed to the pan-tribal communities that attached themselves to the local trade. These marginal groups tried diligently to maintain their tribal identities, but many gradually melded with the local populations. A group of Choctaw seems to have settled near the Adaeseo settlements and Choctaw -style ceramics have been found at Los Adaes. Choctaw identity has survived among the descendants whose ancestors settled along Choctaw and Beech Creeks in Sabine Parish, Louisiana, where they intermarried with the Los Adaes descendants. Others, notably those descended from the southern Choctaw or Yowani, became closely connected to the Caddo, and as ethnologist, John R. Swanton, noted, moved to Oklahoma with them. At least three groups of Choctaw remained identifiable in central Louisiana as late as 1900.

Surviving Adaeseo Communities and their Archaic Spanish Dialect

The complicated roots of the Adaeseos have left a large descendant population along the routes of El Camino Real de Los Tejas in both Texas and Louisiana. Not only are there Hispanic place names, sites and cemeteries but actually living populations that still reflect the dynamics of the 18th century. A series of communities composed of families directly descended from the soldiers and settlers of colonial Los Adaes and its related subsequent settlements at Bucareli and Nacogdoches are strung out along the roads that are now parts of the El Camino Real de Los Tejas National Historic Trail.

The most conservative of these communities are on the Louisiana side of the Sabine River nearer the site of Los Adaes. These include Ebarb-Zwolle and Spanish Lake

where direct descendants dominate the population and where there are connections maintained to the Adaes and Apache as well the 19th-century Choctaw who were somehow connected to the presidial populations in the past. The Choctaw-Apache Tribe at Ebarb and the Adais Nation at Spanish Lake are recognized as Indian entities by the state of Louisiana and both have petitioned for federal acknowledgment as well.

The Hispanic family names of these communities go directly back to the censuses of Los Adaes and of early Nacogdoches. Family names in the Ebarb-Zwolle community include Ebarb (most traced back to Alcario Ybarbo or Antonio Gil Ybarbo), Sepulvado,

Procell (Procella), Parrie (Parilla), Martinez, Lopez, Remedies (Ramirez), Castie (Castillo), Leone (Leones), and others. Mora, Nieto, Flores, Sanchez, and Corrales are the dominant families in Spanish Lake area.

On both the Louisiana and Texas side of the Sabine River many Hispanic family names of some communities go directly back to the censuses of Los Adaes and of early Nacogdoches. The recognition of Indian heritage and ancestral affiliation on the Texas side seems to have suffered more from Anglo-American contact. This may be attributable to the very strong anti-Indian attitudes that developed in the Republic of Texas and passed into early policies of American Texas. The east Texas communities of Chirino, Moral, Luna and

a few other areas around Nacogdoches are clearly linked to Los Adaes.

The regional dialect of Spanish spoken in northwestern Louisiana and adjacent eastern Texas has been noted as one of the most conservative in the New World. Isolated by the rapid influx of Anglo-Americans in the 19th century, these communities have retained Spanish as almost wholly a spoken language, one kept within the families and close communities and seldom heard by outsiders.

Mexicans who came into contact with Adaeseo populations always spoke related dialects but without the archaic words and phrases that best fit the land, vegetation, and broad environments of forested East Texas and northwestern Louisiana. The Adaeseo dialect incorporates French and Indian loan words added as a consequence of the long-lasting contraband trade through Los Adaes and Nachitoches, clearly setting the language apart. New words ceased to be added as contact with Mexico and the southwest declined in the early 19th century. The local Adaeseo dialect became moribund and died out except in a few isolated pockets. Where it did survive the dialect approximates what one would have heard in daily use on the 18th century frontier.

Recent linguistic studies have documented the survival of the language but researchers are sometimes pessimistic about its future as fewer and fewer people speak the Adaeseo dialect. Yet the fact remains that the Adaeseo dialect still survives and has preserved much of the cultural tradition of its original speakers. Likewise the folk traditions—stories, music, material culture and foodways—can still be found in the same communities.

Roman Catholicism remains a strong religion in the midst of fierce Protestantism and adds to the Hispanic traditions in many ways. Churches and campo santos (cemeteries) are centrifugal to all the surviving communities, most of which still reflect the old rancheria settlement patterns of the Spanish and their Indian neighbors/relatives on the Louisiana - Texas frontier. Clusters of homes around la cude (from the French, La Court) or yard link generations to their familial geography. Scattered into little hamlets of kinfolks, these dot the landscape today as they did in the past. Only in very recent times have the hewn log houses that replaced the early French-style post in ground houses begun to be replaced with more modern houses. Shrines to the Virgin Mary and various saints are not uncommon and crosses mark the sites of violent deaths much as they have done for over two centuries.

At small rural stores people buy tamales and chorizo, as well as strings of dried hot chilies and garlic. Church calendars and pictures of the saints remind one of the Adaes roots of local folks. Old timers sometimes chat in Spanish and tell the stories of Gil Ybarbo and Gil Flores going all the way to Mexico City to get permission to move nearer their patria chica, Los Adaes. Perhaps they also recall having heard La Llorona, the Weeping Mother of the Aztec-Hispanic tradition, wandering in the watery sloughs weeping for her drowned child. One can also hear about La Mujer Vestida de Negra who made even the most macho backwoods men run from her in the forest. The mal de ojo now attacks pickup trucks as it once did the horses of haughty riders, and the stories flow about the old ladies who possess that power. One cannot help but recall the amulets (higas or ficas) scattered in the earth at the site of Los Adaes, protection from the Evil Eye.

So, in a world full of English speakers connected by the computer and dependant on the global economy, the old ways linger and the culture of the Adaeseos survives. Doctors, lawyers, priests, anthropologists, nurses, and school teachers boast of Adaeseo roots, and prosperity is finally replacing the economic hard times of the colonial frontier. The culture has integrated the lumber industry and oil fields with its proud cattle and horse ranching, it equestrian economy rooted squarely in the past. Local tourism has encouraged the Louisiana Tamale Fiesta at Zwolle and the Choctaw-Apache and Adai Nation Pow-wows, adding those events to individual expressions of cultural heritage. Traditional fiddle and guitar music still can be heard in homes and churches or local bars, songs so old they have no names, but melodies that connect to the dancing at Los Adaes in the 18th century.

The Future of Los Adaes?

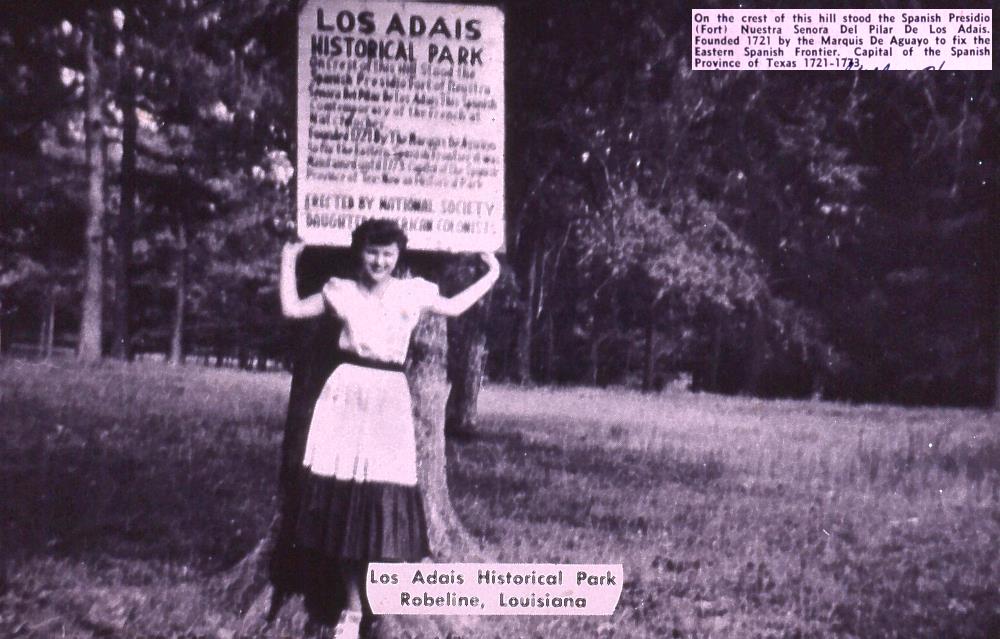

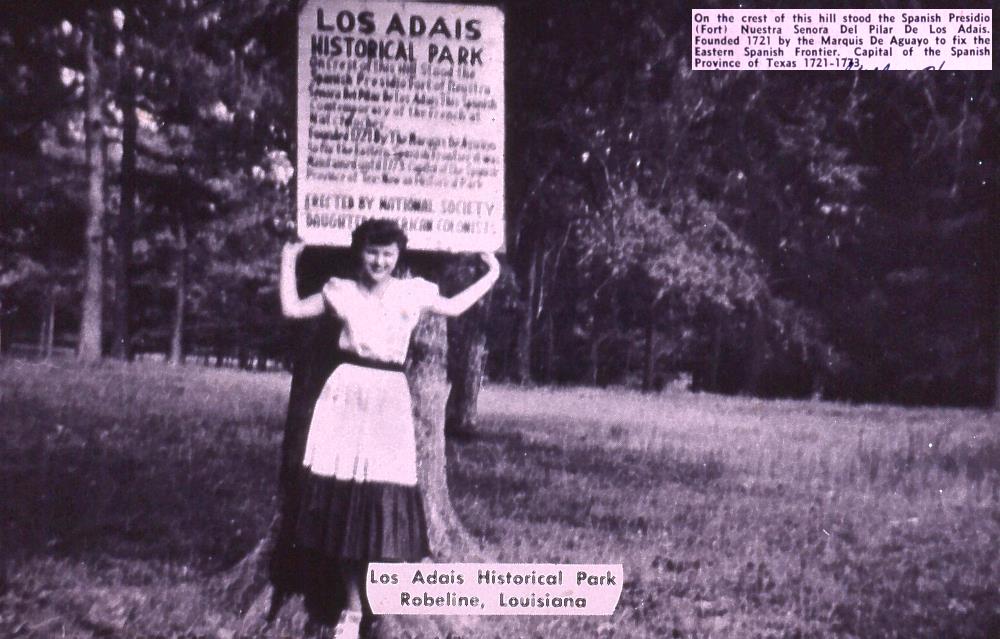

Rescued from oblivion in the national consciousness, the Los Adaes Commemorative Site developed over the course of the 20th century. The Daughters of the American Colonists first recognized the existence of Presidio Los Adaes in 1933 with the donation of land for a commemorative site where it once stood. There they erected a stone monument with a tablet and flag pole to honor the then little-known story that had unfolded 200 years earlier in the great North American wilderness. The Daughters donated the money to Natchitoches Parish to buy the land and it became a small rural park undeveloped save for some clearing and gravel access roads.The Natchitoches Parish Police Jury (County Board) enacted an ordinance in 1970 prohibiting removal of artifacts or damage to the site.

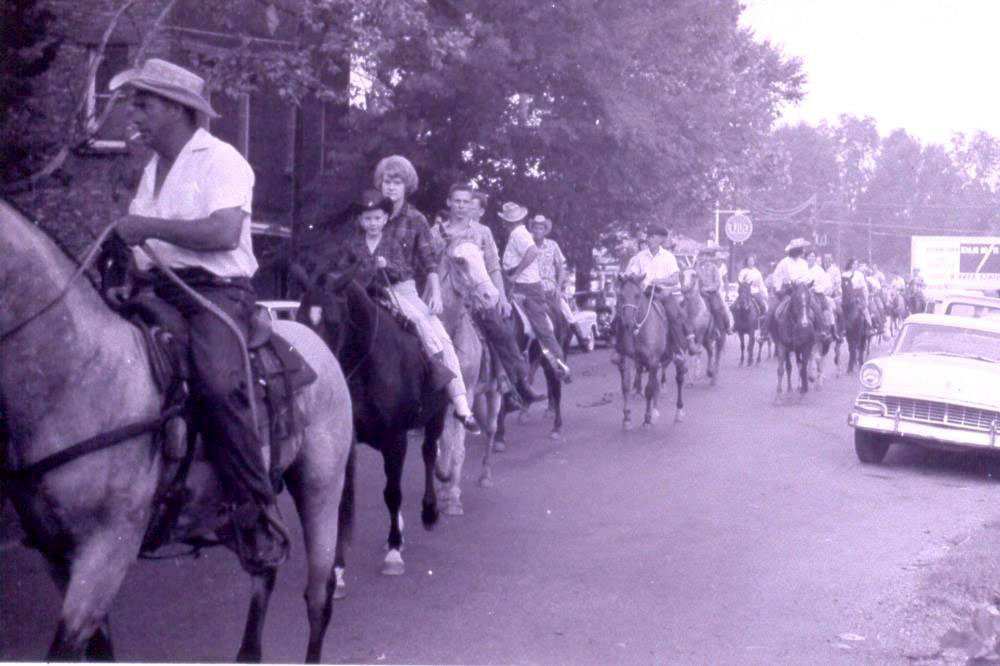

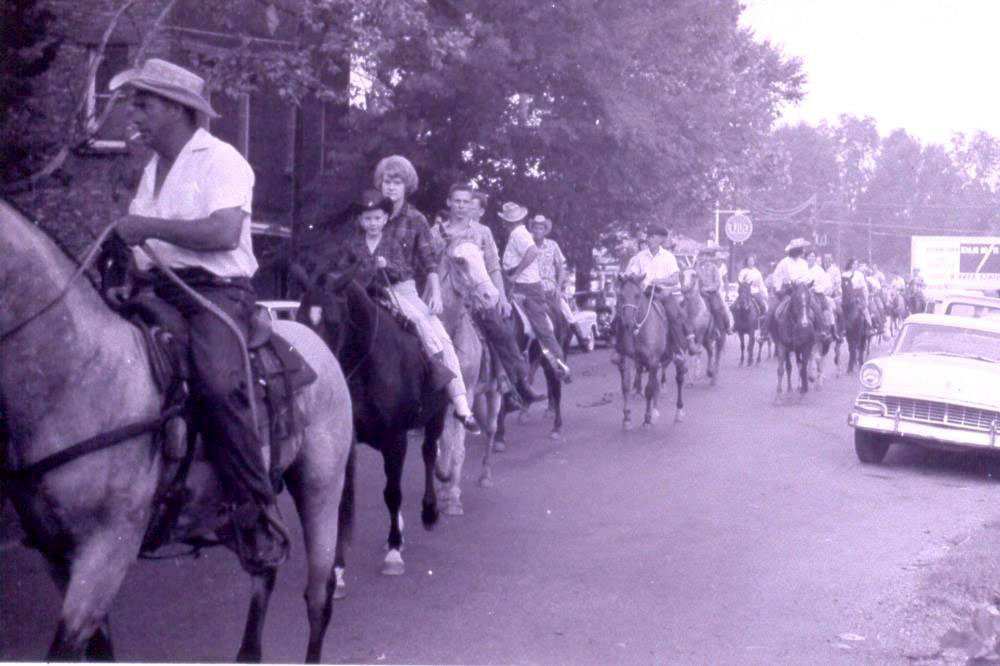

In 1972, the Los Adaes Foundation of Robeline, Inc. was established, and the foundation held trail rides and commemorative events at Los Adaes during the 1970s. Recognizing the continued Adaeseño military tradition, one event honored the heads of the Adaeseño families for their military service in 1977—each veteran was given a plaque. The Los Adaes Foundation, along with Pete Gregory, was instrumental in placing Los Adaes on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

Some twenty years later in 1999 George Avery interviewed elderly descendants from the wave of Anglo-American immigration into the area starting in the early to middle 19th century. They recalled fond memories of youthful romance and family picnics in the hills and pine trees of the abandoned Spanish fort. Some even witnessed U.S. military maneuvers in the area during the Second World War. Many knew the historical importance of Los Adaes and realized that they walked among the spirits of the Adaeseños when they visited the park.

Shortly after Los Adaes was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, it was donated by the parish to the Louisiana Office of State Parks. Los Adaes is now designated as a National Historical Landmark and continues to be a part of the Louisiana State Parks system. Both the parish and the state have protected the site and the Office of State Parks has expanded the protected area to include the western portions of the presidio and adjacent areas associated with the mission/church complex. Park development has been confined to building an archeological laboratory/visitor center, some fencing and access for visitors. A station archeology program at Los Adaes established in 1995 by the Louisiana Division of Archaeology was instrumental in furthering both research and heritage revitalization. Unfortunately, the program was impacted by budget cuts and discontinued in 2005-2006. Park attendants and interpretive rangers keep the site accessible to visitors.

The Los Adaes site became the eastern terminus of the El Camino de los Tejas National Heritage Trail in 2006. As such, it is a vital link in the development of this national corridor. It is virtually the only colonial site on that national corridor that has not been impacted negatively by agriculture or urban development. Archeological investigations to date have been modest in scope and, as much as possible, limited to survey and testing in recognition of the importance of preserving the site for the future. These investigations have established the content and extent of the site and have demonstrated amazing site integrity. Just below the grass lies the largely intact remains of Presidio Los Adaes and the Mission San Miguel.

So what does the future hold for Los Adaes? Preservation and additional research are minimal expectations both for Los Adaes and the El Camino de los Tejas. Care should be taken as is required by the site's nature and its protected status to preserve and present this fragile and unique archeological and historical resource for future generations. The history of Los Adaes is intricately woven into the social and cultural fabric on both sides of the Sabine River that forms the boundary between Louisiana and Texas. Its multi-ethnic foundations and transnational spirit of accommodation for survival in a changing world is perhaps Los Adaes' greatest legacy. |

Northeastern New Spain in the late 18th century.  |

Value of Spanish trade goods in 1782 relative to deerskins in 1782 as established by Antonio Gil y Barbo, Lieutenant Governor of the Pueblo of Nacogdoches. Enlarge to see full table.  |

The Adaeseño dialect still survives in communities along the Texas-Louisiana border and has preserved much of the cultural tradition of its original speakers. Likewise the folk traditions—stories, music, material culture and foodways—can still be found in the same communities. |

Members of the Caddo Nation visiting Los Adaes in 2004. Station Archaeologist George Avery explains some of the strong links between the 18th-century Spanish capital and Caddo peoples. Photo by Dayna Bowker Lee.  |

In a world full of English speakers connected by the computer and dependant on the global economy, the old ways linger and the culture of the Adaeseños survive. Doctors, lawyers, priests, anthropologists, nurses, and school teachers boast of Adaeseño roots, and prosperity is finally replacing the economic hard times of the colonial frontier. |

The Spanish Lake Cemetery located about five miles north of Los Adaes includes the graves of Adaese o descendants. Photo by Pete Gregory, 1963.  |

Flag program held at Los Adaes State Historic Site. Los Adaes continues to serve as a focal point for historic interpretation and for those who trace their cultural heritage to the 18th-century settlement. Photo by George Avery.  |

Related Communities

Louisiana Side of the Sabine

Spanish Lake

Allen

Ebarb

Zwolle

Texas Side of the Sabine

Chirino

Moral

Luna

Nacogdoches |

Stone monument and flag pole base erected by the Daughters of the American Colonists.  |

Plaque recognizing the purchase of the property containing much of Presidio Los Adaes by the Daughters of the American Colonists, who donated the property to Natchitoches Parish in the early 1930s.  |

1954 postcard honoring Los Adaes in the days it was part of a Natchitoches Parish park. The address-side caption is shown in the upper right hand corner.  |

Community trail rides to Los Adaes were regular events in Nachitoches Parish in the 1950s.  |

Los Adaes brochure produced by the Los Adaes Foundation in 1979.  |

Plaque made by members of the Los Adaes Foundation in 1977, some of which were given to Adaese o veterans from the Spanish Lake community.

|

|