|

Los Adaes may have been the official capital of Spanish Texas throughout much of the 18th century but many aspects of life there were far different from that at other provincial capitals. Being at the official end of Camino Real, Los Adaes was a rather forlorn outpost far from Spanish supplies and other Spanish peoples and all but invisible to the eyes of most colonial officials. It was also a place ill-chosen for self sufficiency—poor soils, inadequate drinking water, and no direct access to water transportation routes. The only officially allowed and viable means of subsistence was raising livestock, and that meant carving out small ranches from the forests, most of which were reached only by riding for hours from Los Adaes.

Los Adaes would not have survived for five decades had it not been for three crucial factors:

- the presence of the nearby French trading post of Natchitoches;

- the tolerance, cooperation, and protection of the surrounding Caddo and Adais peoples;

- and the willingness of the Spanish settlers to do what they had to do to survive.

The following glimpses of life at the 18th-century Spanish capital of Texas and its surrounding hinterlands are based on archival records and archeological evidence.

Pioneering Settlement

Los Adaes was more than a military, political, and religious outpost, it was a pioneering settlement. When Aguayo reestablished Los Adaes in 1721, he left behind 100 soldiers, 31 of whom brought their families with them. Most of these original settlers stayed, had families, and became Adaeseños, people who considered Los Adaes their permanent home. At least three generations of Adaeseños were born and raised in the settlement, as reflected by the documented successions of sons who followed their fathers and sometimes grandfathers and served as soldiers at Los Adaes. The Spanish records document mainly those who held paid positions as soldiers, servants, and missionaries. But while the count of those on the payroll declined through time, the overall population grew slowly but steadily as the descendant families of the soldiers grew larger and as soldiers retired and stayed on. Amidst the documented Spanish citizens there were also Indians, French traders, escaped slaves, and ethnically mixed frontier denizens about whom little is known.

After several generations, the officially recognized soldier-settler-citizens and their families numbered some 300 individuals in the final years of the Spanish capital's existence. Yet, when Governor Barón de Ripperdsÿ visited Los Adaes in June 1773 shortly before its abandonment, he estimated that more than 500 people lived at the presidio and on the ranches of the surrounding countryside as far west as Mission Los Ais across the Sabine River. This is probably a realistic population figure for the greater Los Adaes settlement in the latter years of the Spanish capital.

The occupations of those Adaeseños who were not soldiers were mainly listed as farmers, cowboys (vaqueros), and servants, but some are described in various documents as muleteers, carpenters, tailors, barbers, guitar players, blacksmiths, grave diggers, and traders. It is to be expected that in a small frontier settlement, most Adaeseños played different roles during their lives. Most Spanish soldiers would have had dual careers much like the French soldiers at Natchitoches. The soldiers stationed at Fort St. Jean Baptiste worked 48/48: they worked as guards for 48-hour shifts and then spent two days farming, smithing, or doing other civilian work.

While the unmarried Spanish soldiers usually lived at the presidio, those who were married and had children generally resided outside the compound where they carved out their own farms and ranches. The soldier-citizens who became officers and minor officials serving under the governor were the main individuals who had the necessary social position, wherewithal, and the governor's permission to establish substantial ranches.

Yet through time as the population dispersed into the countryside smaller farms and ranches also came into existence. Family labor was used to clear the woods, build houses, raise livestock, and tend gardens. But the Adaeseños were, in essence, tenants beholden to the governor for seeds, farm equipment, weapons, gunpowder, and other basic goods like soap, sugar, and clothing. The ordinary soldiers were also expected to raise crops and tend the livestock of the governor. As Father Velasco, a Franciscan from Mexico City put it in 1746, the "poor soldiers are prisoners of the governor," and the governors are "sovereigns to whom the settlers are supposed to give tribute."

Adaeseo Ethnicity and Social Status

The soldiers and settlers who came to be known as Adaeseños were mostly poor peasants of mixed ethnicity and low social status. Through time the community grew, as many soldiers had sizable families and stayed at Los Adaes when they retired from the military. Although a few gained social status through service and sometimes marriage, most Adaeseños remained impoverished frontier denizens.

The 100 Spanish soldiers who were recruited to come to Los Adaes in 1721 came from various towns such as Saltillo, Zelayla, and Zacatecas in what is today northern and central Mexico. Most were poor second-class citizens. In fact, many of the 500 soldiers recruited for the Aguayo expedition to Texas were taken from New Spain's jails and given the chance to be set "free" by agreeing to serve in the military and be stationed on the remote frontier.

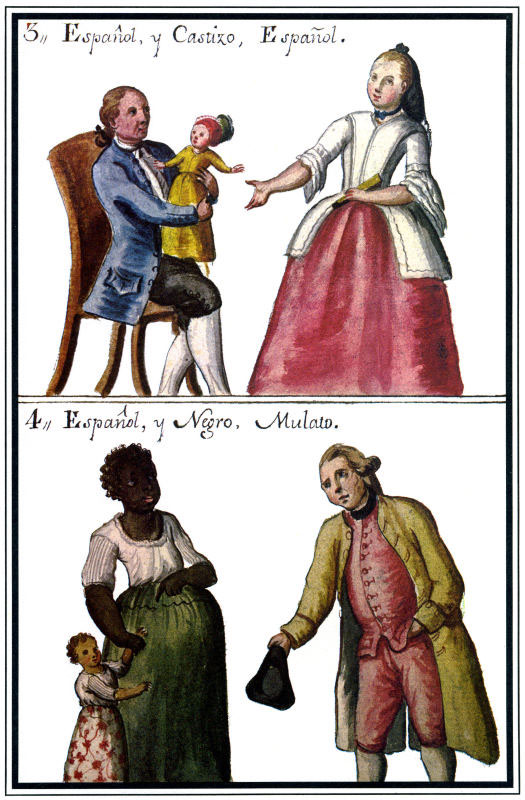

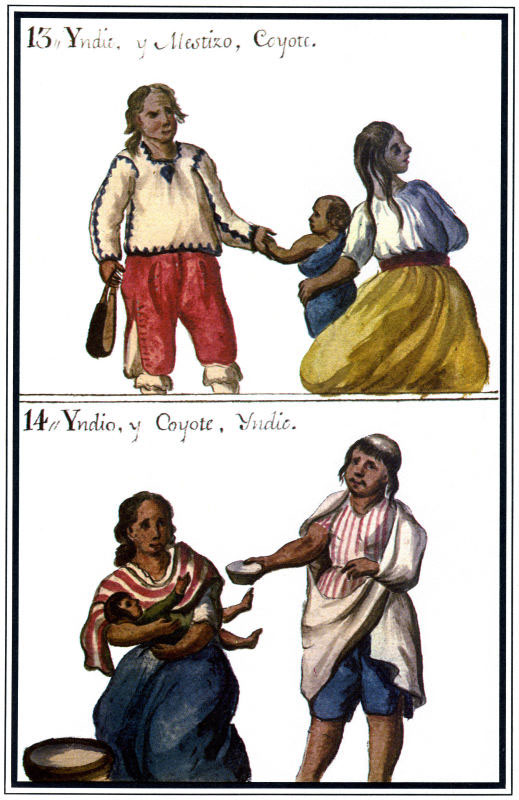

Eighteenth-century New Spain was defined by a society that ranked aristocrats born in Spain at the top of a racial and social hierarchy that had Native Americans and slaves at the bottom, with those born of mixed ancestry and New World colonial heritage somewhere in between. One's calidad, or social status, was designated by a casta label that greatly constrained social position, career advancement, and wealth.

The casta classifications designate various ethnicities and admixtures. For example, the offspring of an Espaol—someone of Spanish descent—and Indio or Indian was referred to as a Mestizo; the offspring of an Espaol and a Negro or African was a Mulatto; and the offspring of an Indian and Mestizo was a Coyote; while the parents of a Lobo were an Indian and a Mulatto. Among the 60 soldiers who remained stationed at Los Adaes after 1727 (when the presidio's force was reduced from the initial 100 to 60), 29 were classified as Espaol, 13 were Mestizo, 9 were Mulatto, 7 were Coyote, 1 was a Lobo, and 1 was an Indio.

These casta categorizations were not as rigid as they may seem, as they were often based on the impressions of the Spanish officials and priests who recorded the designations for various purposes. Spanish documents show that some individuals were assigned to different castas at different times. A person's casta could be "improved" by government service, such as valor as a soldier engaged in frontier warfare against Apache and Comanche "heathens." Soldiers officially assigned to Los Adaes were often sent to man other presidios further to the west, such as San Antonio de BZ¿xar and San Sabsÿ, where Spanish-Indian relations were often hostile.

Through this process, some Adaeseño soldiers acquired the highly desired honor of being called an Espaol, yet only a few earned the elevated status of being called don. Born at Los Adaes in 1729, don Antonio Gil Ybarbo became the highest ranking Adaeseo because his father was born in Spain and by virtue of his own distinguished military service. It was he who led a group of former Adaeseños back to East Texas in 1779 to establish the town of Nacogdoches.

Social relations within the Los Adaes community were constrained by a hierarchy shaped like a "rough diamond," as historian Francis Galán put it. The governor and the few high-ranking officers he brought in from elsewhere in New Spain were at the top—they were Españoles who had high social status and privilege relative to all others at Los Adaes. The true Adaeseños— rank and file soldiers, their families, and fellow settlers—formed a broad middle group that included ordinary officers, cowboys, muleteers, and missionaries. At the bottom of Adaeseño society were a few Christianized Indians, captive Apache slaves, and escaped African slaves.

Unlike the two extremes of society, most Adaeseños were not exclusively defined by their calidad. Social mobility depended greatly on the whims of the Spanish governors above all else. While few Adaeseños entered the governor's inner circle or married into wealthy families at French Nachitoches, those who claimed legitimate birth, behaved properly, attended church, and remained loyal to the Spanish Crown still earned personal and family honor.

Tri-Ethnic Accommodation

Herbert Bolton was the first of many historians to call attention to what he called the "kinship diplomacy" between the Spanish at Los Adaes and the French at Natchitoches. Later historians and archeologists have brought out the roles that Caddoan peoples played as well in the establishment of what archeologist Pete Gregory calls a "tri-ethnic" culture at Los Adaes. The five decades during which Los Adaes existed as an official Spanish outpost represents a historically unique example of prolonged direct contact and day-to-day interaction between Spanish, French, and Caddoan peoples. In contrast to the exploitation and domination that characterized most Spanish-Indian settlements, and the confrontational nature of earlier Spanish-French encounters in the New World, 18th-century Los Adaes was a relatively peaceful place where mutual accommodation reigned.

The relationships among Spanish, French, and Caddoan peoples were based on cooperation, accommodation, and mutual support. Two key factors explain this tri-ethnic cooperation, the military strength and reputation of the Caddoan peoples and the shared frontier setting of the two European settlements.

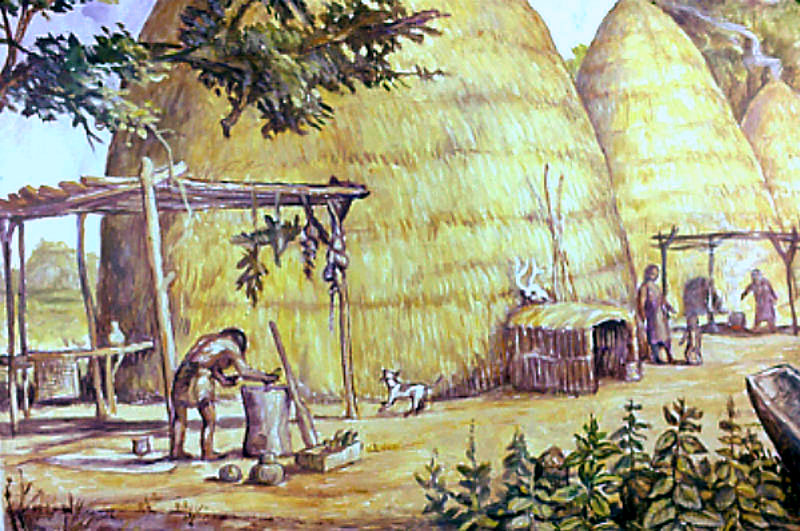

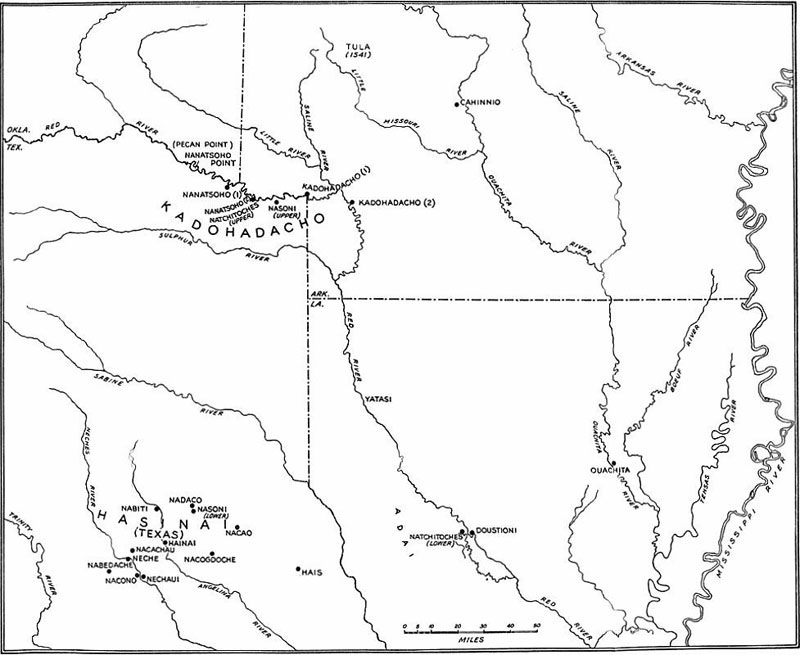

Caddo-speaking groups had dominated and defined the cultural geography of the eastern part of Spanish Texas for at least a thousand years. And although their populations were in swift decline as early as the late 16th century, as the result of the introduction of Old World diseases, Caddo peoples were still numerous in the days of Los Adaes. Famed anthropologist John Swanton estimated that the various Caddo-speaking groups numbered upwards of 10,000 peoples in the early 18th century. By then the Caddo tribes were allied with other tribes to the west such as the Wichita, who were themselves allied with the Comanche, who had become the most feared mounted raiding society of the Southern Plains. The Caddo, therefore, did not need the protection of either the Spanish or the French. In fact, it is likely that the Caddo groups could have forcibly removed European peoples from their ancestral lands throughout the 18th century. Instead, they invited both the Spanish and the French into their homeland, provided that the visitors behaved, and that the Caddo continued to benefit from their presence.

Although the French arrived in the region over a century after the first Spanish expedition encountered the Caddo world in the mid-16th century, they set the tone of the sustained European intrusion into the region by establishing economic and social relations with both Caddo peoples and the Spanish. The French practice of unrestricted trade and intermarriage with both groups and the isolated frontier setting created a situation where each cultural group could freely adopt or reject traits of the other groups without fear of reprisals. Even though the Spanish were officially forbidden to trade anything but essential supplies with the French and they were prohibited from trading guns or alcohol to the Caddo, they had little choice but to follow the example set by the French. Spanish intermarried with both groups, traded extensively, if often clandestinely, and adopted many practices, especially those of the French, such as building techniques.

The French at Natchitoches and the nearby Spanish benefited from and came to depend on one another for many different needs: trade, defense, labor, religious services, social interaction, and marriage partners, among them. Perhaps more than anything the two groups shared European heritage, Catholic religion, and closely related languages. In other words, they shared cultural origins and both groups were living on the frontiers of their colonial empires, far removed from the civilized societies they represented.

The Franciscan priests at Mission Los Adaes were key players in Franco-Spanish relations. They served as the outpost's chaplains who administered sacraments to Adaeseños as well as to the French at Natchitoches. The Spanish priests baptized French children, performed mass, blessed marriages (some of which were Spanish-Franco unions) and witnessed deaths. For instance, when the famed trader and founder of Natchitoches, Louis Juchereau de St. Denis, died in 1744, friar Francisco Vallero of Mission Los Adaes served as official witness at the funeral, which was attended by the governor of Texas, Justo Boneo y Morales.

The Spanish-Franco marriages, although relatively few in number, combined with the celebration of mass and baptisms and feast-day celebrations, drew both border communities into a broader economic and social network. These events brought everyone in the Texas-Louisiana border community together for worship, song, and remembrance including governor-commandants, soldiers, merchants, families, servants, and slaves. Religious occasions were followed by fiestas that gave Adaeseños the opportunity to relieve the stress of frontier life through interaction with their French and Indian neighbors.

Governors: Good, Bad, and Wily

Amidst the overwhelming poverty of the soldier-settlers of Los Adaes, the Spanish governors lived like aristocratic landlords through the personal use of mission lands, household servants, presidial labor, and the monopolization of commerce with the Caddo and French. Between 1721 when Presidio Los Adaes was first established and 1773, when Los Adaes was officially abandoned, 15 governors served there. Most held office for periods of two to four years, although in the later years two governors served terms of seven to eight years. Most governors were relatively wealthy men and former military officers and landowners from more settled parts of New Spain. Many appear to have accepted the position at remote Los Adaes because of the potential to further enrich themselves by controlling the finances of the province and its capital, and by trading with the French, legally or not. This is known because of official hearings and trials which are documented in some detail in archival records.

During the period that Presidio Los Adaes served as the official capital of Spanish, Texas, 1729-1770, residencia proceedings (administrative hearings) were held to review the conduct of seven different governors, some of whom were good administrators and commandants, while others were notoriously bad. Most were also military officers, having served in Spain before coming to Mexico. The recordings of official and often secret investigations give us considerable insight to how the governors operated. These investigations were conducted by an examiner, often the incoming governor, who began the hearing with a lengthy opening statement and then questioned the defendant governor at length. This was followed by the testimony of numerous witnesses (such as soldiers from Los Adaes), various decrees and declarations, and an inventory and review of the presidio's accounts and records during the governor's administration. When the governor's conduct was good, or his service brief, the proceeding records ranged from 100-200 pages long. The longest, that of Governor Manuel de Sandoval, covered over 600 pages.

Governor Sandoval's rule from 1734 to 1737 ranks as one of the worst administrations, at least from the perspective of those who lived at Los Adaes. It coincided with friction between French Natchitoches and Los Adaes over the efforts of Spanish royal officials to define the border between Louisiana and Texas. Despite the official requirement that Texas governors reside at Presidio Los Adaes, Governor Sandoval was seldom present and spent most of his term in San Antonio de Béxar where he directed military campaigns against the Apache. In his absence, Lieutenant Joseph Gonzales oversaw Los Adaes, sending back dismal reports of farming and ranching difficulties due to heavy flooding, which ruined crops and delayed supply trains. Shortages of corn and basic food supplies caused misery and sickness, and the French were sometimes unable or unwilling to sell corn to Los Adaes, because of the continued border dispute, mounting Spanish debt, and the threats to Nachitoches from Southeastern Indian groups revolting against the French. Presidio Los Adaes fell into a poor state of disrepair as rotting walls and buildings were not replaced.

In 1736 things came to a head. The poverty stricken Adaeseños became fed up with their dire circumstances. Lieutenant Gonzales reported that all the soldiers, lacking serviceable uniforms, were dressed in deerskins and that the women and children went about "naked" and too ashamed to even go to church. French creditors were owed almost 400 pesos (equivalent to thousands of dollars today) for necessary supplies provided to the Spanish. Gonzales pleaded to Governor Sandoval to return to Los Adaes to reprovision the presidio and settle affairs. The indebted soldiers were riled because of long overdue pay and refused to follow the usual practice of giving remote power of attorney to the governor until, as Gonzales put it in correspondence to Sandoval, "you settle their accounts and pay them what you can."

The next year Sandoval was gone from office and he was brought up on various charges, including his failure to pay the soldiers under his command. The soldiers claimed that although they had signed power of attorney documents, they received no goods as payment from the governor during his three years in office. As a result of the inquiry, the soldiers finally got what was owed them. Sandoval was bankrupted and sent to prison.

The administrative proceedings reveal that Sandoval and his right-hand man, first Lieutenant Ferm?n de Ybericñ were also accused of untoward behavior and suspiciously close relations with the French at Natchitoches during one of the rare occasions that Sandoval visited Los Adaes. Sandoval and Ybericñ were said to have returned to the presidio from a trip to Natchitoches with three French women in tow, one of them the wife of a French official. The group had a party in the Governor's house and, when it appeared that the married woman had spent more time there than was deemed proper, the mission priest stepped in and removed the woman. The political and legal controversies surrounding Sandoval continued for years, but he was eventually exonerated, released from prison, and returned to military duty.

In contrast, Governor Tomás Felipe de Winthuisen, who served from 1741 to 1743, emerges as one of the best administrators. During his term he renovated the stockade, built government buildings, added five new barracks, improved the farms, and encouraged the growth of the community. In contrast to most governors, Winthuisen did not permit or participate in illegal trade with the French. After leaving office, he wrote a 1744 report that recommended the garrison at Los Adaes be further reduced from 60 to 40 soldiers, reasoning that this would reduce opportunities for illicit trade. He argued that not even 600 Spanish soldiers would be enough if the French and their Indian allies actually decided to attack Los Adaes. The governor's candid assessment is yet another indication that the remote Spanish capital was merely a symbolic barrier to French colonial expansion, one that had little negative effect on the lucrative French-Caddo trade.

Most other governors who served at Los Adaes were neither as controversial and corrupt as Sandoval nor as effective and moral as Winthuisen. Several were charged with serious misdeeds including allowing the presidio to fall into disrepair, using soldiers for tasks related to the governors' personal benefit, charging inflated prices to the soldiers and settlers, and refusing to buy seed corn grown by the settlers. While many of these charges must have been valid, most were dismissed and few governors were actually held accountable for their actions. The transcripts of the administrative hearings are full of contradiction and political intrigue. Flowery laudatory testimonies suggest the governor bribed or otherwise coerced some soldiers to undermine the credibility of those who lodged complaints.

At the 18th-century Spanish capital, the Texas governors welded power for good and naught. While at Los Adaes they were far from the eyes of Spanish authorities and insulated by distance from the resources and luxuries of New Spain. On the remote Texas-Louisiana frontier, they lorded over their own little fiefdom.

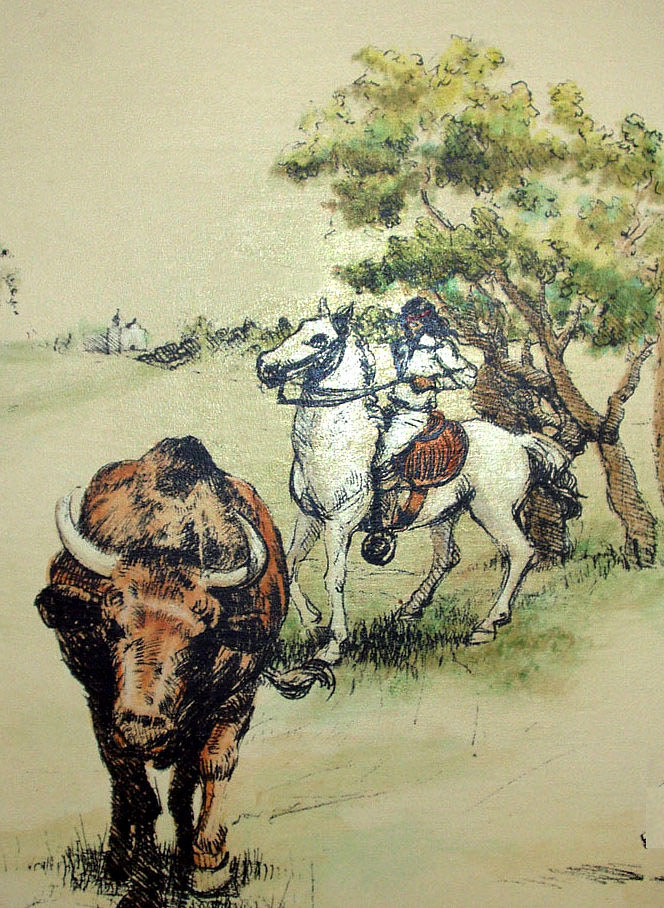

Ranching

Ranching formed the basis of the local economy for the Los Adaes border community and represented the only true economic niche that Adaeseños had for entering into the dynamic and potentially lucrative French-Caddo trade. Initially ranching was done on a small scale and the cattle, sheep, and horses were owned by the presidio and the mission. But through the decades ranching grew in importance and ranches owned by Adaeseños were established in the surrounding countryside, some being many miles distant. The ranches served as points of contact with Caddo and Adai Indians and French traders who traveled along the established upland paths and waterways that functioned as back country transportation routes along which contraband flowed.

The names of various Spanish ranches are known that were connected to Los Adaes. Rancho El Baño (the Bath), located south of Los Adaes, belonged to the mission. Rancho de los Tres Llanos (the Three Plains) was along the Camino Real to the west of Los Adaes. The most famous and probably the largest of them all was El Lobanillo (the Wart), which was located east of the Sabine River just before reaching Mission Los Ais on the Camino Real. This ranch was owned by the Gil y Barbo family (often written Ybarbo) and figured prominently in the later history of Los Adaes. When Los Adaes was ordered abandoned in 1773, the headquarters of El Lobanillo was a small pueblo (town) said to be home to fourteen families comprising some 65 people.

Ranching was a strenuous undertaking in the pineywoods. The forests had to be cleared, livestock had to be guarded and tended, and all necessities had to be brought from the presidio or obtained through barter or ingenuity. Labor was provided by soldiers and their families. Unlike the French at Nachitoches who depended on (and owned) large numbers of African slaves for ranching and farming labor, the Spanish had few slaves. Slavery was officially forbidden in 18th-century New Spain, although exceptions were made for captured Lipan Apaches, some of whom came to live in the Los Adaes area.

Despite the odds, the Spanish succeeded in raising cattle, sheep, horses, and mules. Smoked meat was one of the few food commodities they could consistently produce. Spanish livestock was highly sought after by the French at Natchitoches and elsewhere in Louisiana, so much so that demand outstripped the locally raised herds. Los Adaes ranches were initially stocked, and later restocked, with animals driven to Los Adaes from south Texas as part of the periodic supply trains that arrived with, or were sent by, the governors. For instance, in April 1731 Governor Juan Antonio de Bustillo y Zevallos arrived at Presidio Los Adaes from Presidio La Bah?a with 200 horses, 250 cattle, and 500 head of sheep. Such Spanish cattle drives and the ranches of Los Adaes helped establish a characteristic pattern of Texas frontier life.

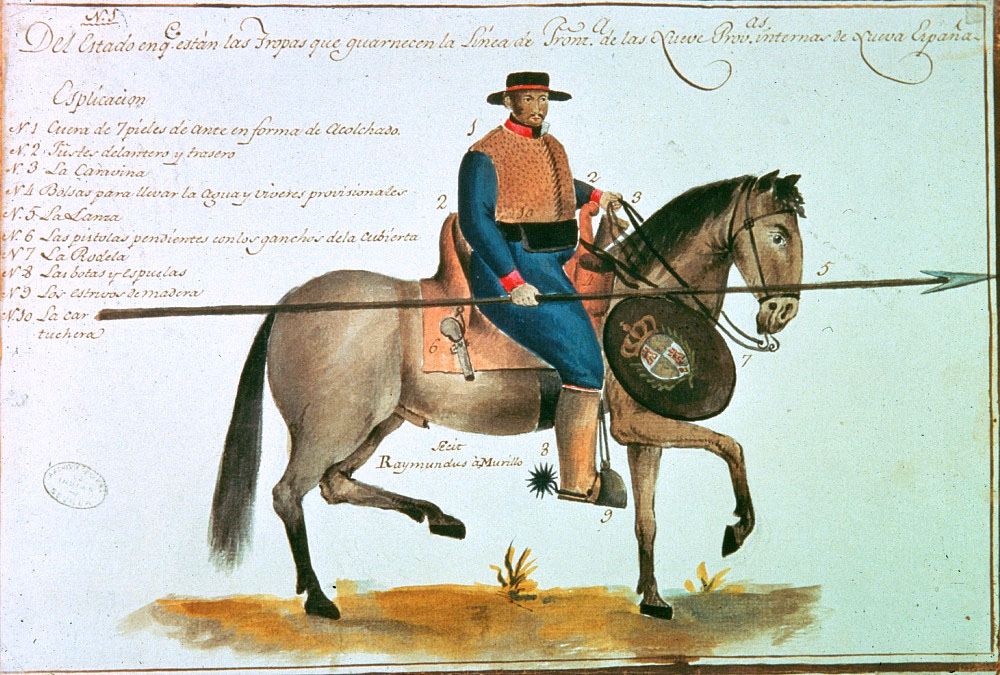

A vivid description of eighteenth-century Spanish vaqueros, the original Texas cowboy, was written by the French traveler Pierre Marie François de Pag?s, who was struck by the appearance and behavior of the soldier-cowboys he encountered at Los Adaes in 1767. He described the inhabitants of Los Adaes as a "species of cavalry" who enjoyed:

relating their exploits in battle, [and] the perils and hardships they have encountered in the wild and inhospitable regions on horseback in visiting and taming their cattle. Their bodies are strong and muscular, though sadly broken by their severe campaigns against the savages or by the no less ruinous consequences of their youthful debaucheries.

The half-savage Spaniards of this settlement are dressed in a most fantastic manner: a sort of under-waistcoat and breeches without a seam, but pieced together with buttons of gold and silver, and commonly ornamented with lace, stockings made of skins, and shoes whose upper-leathers are cut into thongs, affording free access to dirt and dust as well as the air . A large hood and short cloak adorned around the neck with broad stripes of gold lace, seems to be considered as a full uniform, and is only worn on horseback. But in spite of all this finery, one often meets the Spaniard without either hat or shirt, while his sumptuous uniform, torn by the briars and thorns of the woods, hangs in a thousand tatters about his person. His heels are usually armed with a pair of enormous spurs about five or six inches in length. His armor consists in a helmet of deer-skin, a carbine, and a long broadsword. Two little leather boxes placed before the saddle serve to hold provisions for his march. The carbine rests commonly on the stock, but is used as a pillar, during the night, for a kind of tent, which is [raised] occasionally with the Spanish hood, in order to protect him from the rain. His saddle leathers, neatly dressed, and stamped with various ornamental designs, are garnished around the edges with trinkets of steel, which, like as many little bells, are kept perpetually ringing by the motion of the horse. The rider rests his feet in a couple of stirrups of at least fifty pounds in weight to keep the horseman steady in his seat. The bits of their bridles, which are of an oblong shape, and extremely well adapted to their purpose, have a strong resemblance to those in use among the Arabs, who, as everyone knows, excel in the art of horsemanship [above] all other nations in the world.

In [conclusion], the half-savage Spaniard, with all this singular extravagance, is an excellent rider, and when completely equipped and mounted, never failed to revive in my mind all the ideas of ancient chivalry.

-Monsieur de Pag?s, 1791

Trade and Contraband

The remoteness of the Louisiana-Texas frontier from legal Spanish ports of entry in the New World and proximity to French Natchitoches made Los Adaes what Francis Galán called a "smugglers' paradise." The governors monopolized local trade and outside Spanish officials could not stop the burgeoning contraband in hides, horses, cattle, guns, captives, tobacco, alcohol, ironware, and other goods. The proximity to French Louisiana, the cloak of the pineywoods, and the many Indian trails and waterways linking Los Adaes and its outlying ranches with Caddo settlements and Natchitoches perfectly situated Adaeseños to take part in the thriving frontier trade. Those who did so at the behest of, or in cahoots with the Spanish governors, profited from the illegal activity, but those who challenged the governors' powerful monopoly often suffered.

Adaeseños began trading with the French in the early 1720s out of economic necessity—their farms failed and Spanish supply convoys from San Antonio were delayed for months because of the "insurmountable difficulties confronting them for the transport of goods over 400 leagues (600 miles) and so many impassible rivers and creeks," as Governor Almazsÿn put it in 1724. Faced with dire need, the governor allowed open trade with the French, livestock and cash for grains and other necessities. These exchanges, and the increasing reliance of the French on the Franciscan missionaries for religious services, established commercial and social networks that would continue to play a major role in life at Los Adaes throughout its history.

Officially, Adaeseños were forbidden to trade with the French except for essential perishable supplies when these could not be hauled in from elsewhere in New Spain. It is said that not a single Adaeseño or governor ever formally admitted to conducting illegal trade. Yet, virtually all of archival records of the residencias, or job performance reviews, of the Texas governors contain accusation after counter-accusation by Adaeseños that their governors and fellow citizens did just that. Periodic frontier inspections turned up ample evidence of the thriving illegal trade. From these and many other sources of information, the royal authorities in Mexico City and beyond, all the way up to the Spanish king himself, became well aware of the growing colonial economic problem, of which the Texas-Louisiana contraband was merely one example. The Spanish Crown struggled to maintain its rigid monopoly over New Spain's trade and commerce and to keep profits flowing back to Spain. The success of the competing and more flexible French mercantile system was seen as a great threat, and nowhere was this more apparent than in East Texas.

The legally permitted trade in grain and livestock with the French in Natchitoches and the exchange of certain Spanish trade goods (such as glass beads and cloth) for deerskins and buffalo hides with the Caddo served as cover for a much more robust and lucrative contraband network. From the Caddo and other Indians the French sought deerskins above all else, a commodity highly prized in Europe. But Indian sources also provided bison hides, Apache slaves, horses, salt, and corn. Although never mentioned as a trade item, Caddoan pottery has been found in great abundance at Los Adaes, some of it made in non-native styles mimicking European pottery forms. The French sent the Indians guns, gunpowder, alcohol, ironware, cloth, tobacco, and vermilion (brilliant scarlet pigment made from cinnabar), among other items. While the Adaeseños could provide only livestock and cured meat, they served as middlemen and traffickers, hauling loads of skins and hides to Natchitoches and bringing back the French goods sought by the Indians and by the Spanish themselves.

The outlying ranches of the Adaeseños served as secret rendezvous points for contraband operations beyond the presidio walls. The smuggling center of the Spanish-Franco-Caddo trade was the Bayou Pierre settlement northwest of Natchitoches and northeast of Los Adaes. Bayou Pierre is the name given to the westernmost channel of the Red River, which in the 18th century formed a twisting back-swamp waterway that ran through Spanish Lake and connected up with many smaller drainages and back lakes. Trade goods could be moved by dugout canoes in the waterways and by horseback along the nearby upland trails that had long been used by the Caddo. Bayou Pierre remained a center of illicit commerce long after Los Adaes was abandoned.

The 1750s proved to be the golden age of Spanish smuggling on the Texas-Louisiana frontier. New territory opened up in 1755 with the establishment of Presido San Agust?n with access to additional French and Indian traders on the lower Trinity River. The decade coincided with the French and Indian War when French needs were the greatest to fight their British enemy elsewhere in North America. Governor Barrios y Jáuregui, 1751-1759, used his position to tightly control the illegal trade for his own benefit. He used his troops to traffic goods, especially skins and hides, and he is said to have amassed more contraband wealth than any Spanish governor. The extent of the governor's involvement was documented by the investigation of his predecessor, Governor Angel Martos y Navarette.

The testimony of Juan Antonio Maldonado, an Adaeseño muleteer and loader for Governor Barrios y Jsÿuregui, and that of Lieutenant Joseph Gonzales provide fascinating details of the contraband trade. Maldonado stated that "many times he brought guns, ammunition, gunpowder, and the rest of the trafficked goods from Natchitoches to take to the Indians" and that on a "couple of occasions he returned with hides, chamois of buffalo, and horses, which were distributed among the company" at Los Adaes. Gonzales' sworn statements show the magnitude of the trade in deerskins and buffalo hides. "On several occasions they took 1,500, and other times 1,000, and still other times 800." And Lieutenant Gonzales knew this well because he was the manager of the governor's store at Presidio Los Adaes. Francis Galán estimates that Governor Barrios y Jsÿuregui used his troops to transport nearly 80,000 buffalo hides and deer skins during the eight years he was in office.

The fur trade was not the only cause for alarm to Spanish royal officials. The high quality tobacco grown by the French at Natchitoches was so valued that it served as de facto currency for the cash-strapped Spanish soldiers. Franciscan missionaries were said to have used Adaeseño soldiers to transport French tobacco and other goods between Texas' missions. Of even greater concern was the smuggling of alcohol—French brandy and wine— among Adaeseños, Indians, and African slaves along the Texas-Louisiana border. As the commander at Natchitoches put it in 1771 (after the French post had became part of New Spain), the contraband trade in alcohol was "cause for very serious consequences, and now the barter of horses and clothing, which, at all hours of every day the soldiers of Los Adaes secretly conduct."

The thriving and unstoppable contraband trade was cited by MarquZ¿s de Rub? as one of the justifications for recommending that Los Adaes and most other remote Spanish outposts in Texas be abandoned.

|

Historic re-enactors in 18th-century garb travel along a trail through the pineywoods. Photograph by George Avery.  |

Historical interpreters portraying Spanish soldiers at Los Adaes receiving an important visitor. Actually, the interpreters were preparing for a visit from the Spanish Duke of San Carlos, who visited Los Adaes SHS in fall of 2003. Photograph by George Avery.  |

Historical interpreter Rhonda Gauthier is preparing hominy as part of a public program at Los Adaes SHS and demonstrating one of the many labor-intensive food preparation methods used by the Spanish in the 18th century. The ash from oak has been added to a pot of boiling corn. The lye in the wood ash causes the corn kernels to expand and thereby lose their outer skin. The resulting hominy must be washed at least seven times to remove the lye before being ground to a paste which will be made into tamales or tortillas. Photograph by George Avery.  |

Mestizo and Lobo castas as depicted by O'Crouley in 1774.  |

Espanol and Mulatto castas as depicted by O'Crouley in 1774.  |

Coyote and Indio castas as depicted by O'Crouley in 1774.  |

Artist Ed Martin's depiction

of a Caddo village scene similar to those witnessed by Henri Joutel in 1687.

Courtesy Arkansas Archeological Survey.  |

Anthropologist John Swanton's map showing the approximate locations of some of the named Caddo groups and villages, as recorded by the Spanish and French in the late 1600s and early 1700s. From: Source Material on the History and Ethnology of the Caddo Indians, 1942, Smithsonian Institution.  |

French Fleur-de-Lis Flag used in 18th century. |

Young's Bayou where it crosses highway LA-6 between Robeline and Natchitoches is thought to mark the 18th- century boundary between French and Spanish territory. Young's Bayou is part of the drainage that the Spanish referred to as Arroyo or Rio Hondo. Photo by Steve Black.  |

October 12 is the feast day of Our Lady of the Pillar, for whom the presidio at Los Adaes was named: Nuestra Se ora del Pilar de los Adaes. The banner to the left was created by Linda Harvey following a description of one the banners from the Aguayo expedition. The banner depicts Our Lady of the Pillar, the name given to the Virgin Mary for her appearance in Spain. Photograph by George Avery.  |

Historical interpreter Cornial Cox is dressed in a similar manner as the Texas governors at Los Adaes may have appeared in formal uniform. Photo by Steve Black.  |

Famed trader and founder of Natchitoches, Louis Juchereau de St. Denis as portrayed by historical interpreter Robert Norment. St. Denis was the most influential French leader along the French-Spanish frontier during the early to mid-18th century. His actions greatly impacted Spanish life at Los Adaes. For instance, Caddo peoples had tremendous respect for St. Denis and were much more interested in trading and forming alliances with the French than the Spanish. The Spanish regarded St. Denis as a major threat to their ambitions. Governor Justo Boneo y Morales is said to have been greatly relieved when St. Denis died in 1744.  |

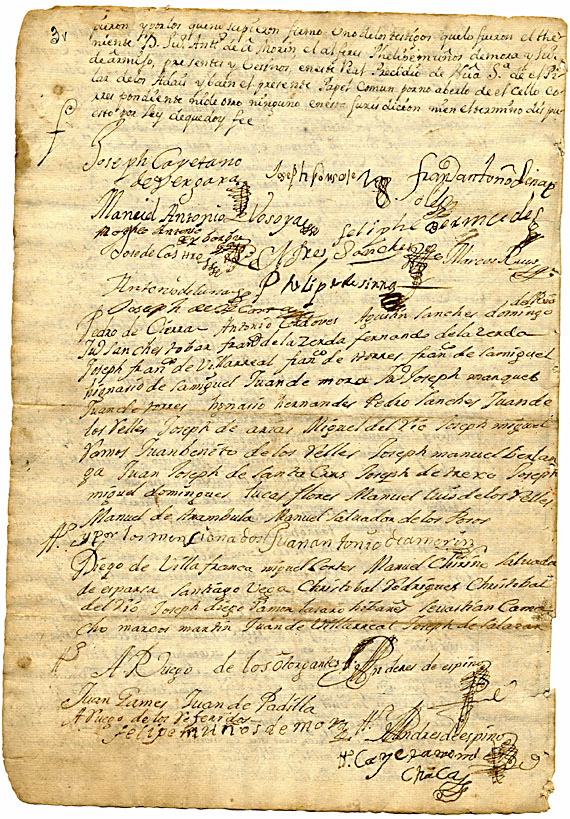

Signature page, Power of Attorney, January 24, 1738 at Presidio Los Adaes, those officers and soldiers who knew how to write their own names signed the document, for example, Lt. Joseph Gonzales, Mateo Ybarbo, Philipe de Sierra, Joseph de Acosta, Felipe Bermudes and Marocs Ruiz. Those who were illiterate, including Juan de Mora, Manuel Chirino, Antonio Cordoves, Domingo del Rio, Francisco de la Cerda and many more, had testigos (witnesses) sign for them. According to historian Francis X. Galsÿn, such power of attorney and many subsequent ones became sources for abuse of the Adaesa o troops. Source: BZ¿xar Archives, Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin (Box 2S26).  |

Historical interpreters portray the Spanish soldiers from Los Adaes who came to the defense of the French and their Caddo allies at Fort St. Jean Baptiste (Natchitoches) in 1731. The combined French-Caddo-Spanish force repelled a concerted attack by the Natchez Indians, a powerful Southeastern group then attempting to push westward. This event helped build a spirit of collaboration among the Spanish and French stationed on the remote frontier. Photo by Robert Norment.  |

Historical interpreters at Fort St. Jean Baptiste dressed as French Jesuit priests. Until the 1750s, the French at Natchitoches had no resident priests and relied on the Spanish Franciscan priests at Los Adaes. Photo by Robert Norment.  |

A 17th-century Spanish drawing of a freshly equipped cavalryman of New Spain. Pierre de Pag?s found the soldier-cowboys he encountered at Los Adaes in 1767 much less refined, as he put it, "half-savage Spaniards." Drawing in the Archivo de Indias, Seville.  |

A native tends cattle on a Spanish mission ranch. Painting, depicting a scene in south Texas, courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

White-tailed deer were the favored prey for Caddo hunters and the main source of meat throughout Caddo history. During the 18th century finely tanned deer hides - chamois - were one of the principal commodities in French-Caddo trade. Courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Replicas of 18th-century French trade goods displayed on a French "veste" or sleeved waistcoat. See enlarged image caption for details. Photo by Robert Norment.  |

Replicas of 18th-century French trade goods displayed on a trade blanket. See enlarged image caption for details. Photo by Robert Norment.  |

Interpretive scene at Fort St. Jean Baptiste, depicting goods involved in the robust French-Caddo trade. Tobacco grown by French farmers near Natchitoches is said to have been the best on the frontier. Caddo deer skins were highly valued trade standards, often exchanged for French iron kettles. Photo by Robert Norment.  |

Historical interpreters portraying French traders taking advantage of the waterways of the French-Spanish frontier. Canoes (most were probably dugouts rather than the simulated birch bark canoes shown here) allowed the French and Caddo to move trade goods through terrain and wet-season conditions that thwarted the Spanish, who relied on horses. Photo by Robert Norment.  |

Historical interpreters portraying French soldiers stopping overnight during a frontier scouting mission. Both French and Spanish soldiers used similar light-weight shelters while on the move. Photo by Robert Norment.  |

|