|

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the eastern part of the province of Texas was a forested wilderness quite unlike the deserts and mountains of northeastern Mexico from which most Spanish expeditions set out. Leaving Saltillo or San Juan Bautista, travelers along the Camino Real de los Tejas plodded along trails that cut a rather striking ecological transect from west-southwest to east-northeast. Ever so gradually they saw the landscape shift from arid to moist, from endless expansive vistas to closed-in woodlands, from low thorny bushes to intermittent trees to tall towering pines. They passed through thick brushy swatches and inviting prairie grasslands and crossed streams and rivers that became wider and more frequent as they neared the eastern frontier. The first wave of soldiers, settlers, and priests finally reached the Los Adaes area in 1717, the second wave in 1721. The citizens of New Spain found themselves in a fundamentally different environment from that where most were born and raised.

The years 1721-1723 saw the construction of the mission and presidio at Los Adaes. The sites chosen were two adjacent "hills" perhaps better described as hill spurs or minor upland ridges separated by a small spring-fed branch that flowed intermittently. The Spanish claimed that they selected this spot because of its convenient source of water and the surrounding relatively flat land they thought would be suitable for agriculture. It proved to be a poor choice that belied the stated reasons; the tiny branch withered to a trickle in dry seasons and the soils all around were poorly suited for raising crops, as were the forested environs. More likely, the "hills" beckoned because they seemed defensible to the military commander, Aguayo, leader of the 1721 expedition to reestablish Los Adaes and keep the nearby French in check.

From today's perspective, the site lies within the northwest uplands, the largest natural ecological division in modern Louisiana. Los Adaes is situated along an upland ridge or divide that runs east almost to the Red River at Natchitoches. The raised terrain made for a natural overland transportation route then, as it still does today (more or less Route 6). The ridge is underlain by sandstone, but there is only one modest outcrop anywhere near Los Adaes. The surrounding soils on the higher slopes and flatter terraces around Los Adaes are difficult to till and have low fertility, as the Spanish quickly learned. Even the livestock grazing potential of most of the surrounding area was limited due to poor soils, dense forest cover, and the land's susceptibility to erosion when cleared.

The flat "plains" would have been just west of the site, toward the small modern town of Robeline. "Plains" would have been a relative and somewhat euphemistic characterization describing an area that was more open and flat compared to the densely forested uplands. The open area may have been one of the "pocket" prairies or natural clearings described by later travelers, and the area remains open as cleared pastureland today.

To the north and east of Los Adaes winds the Red River, some 15 miles away at its nearest point at Natchitoches, which is almost due east of the site. To the north of Los Adaes, the uplands soon give way to a wide section of the Red River valley that is crisscrossed with water features that today are variously called bayous (creeks), sloughs, chutes, lakes, and swamps. This dissected lowland terrain formed over millennia as the Red River carved and re-carved its main channel and side channels, meandering back and forth between resistant uplands. The active channel of the Red is flanked by overgrown natural levees breached by the larger bayous draining the swamps and wet season lakes that filled abandoned river channels, floodplains, and flood chutes. Timber rafts sometimes blocked the Red and its larger tributaries, backing water into the lowlands.

In the 18th century the lowland "raft lakes" and "back swamps" were extensive and very important landscape features. Over the past two centuries most of the large bodies of water have been drained and cleared for farming and ranching, such as the area that begins about five miles north of Los Adaes that is known as the "Old Spanish Lake Lowlands." During the Spanish years this was known as "Laguna de los Adaes," so named because the Adai Indians lived around it. After the Spanish left, it became known as "Spanish Lake." The Aguayo expedition's diarist described this lake as follows:

The Great Lake of the Adaes, ten leagues in circumference, is located a league from the presidio and through it flows the Cadodachos River [Bayou Pierre]. This river goes to Natchitoches, and covers sixty leagues. In the lake there are all kinds of fish, and a great quantity of ducks can be found there all winter.

For the Adais and other native groups such lakes were critical habitats supporting water-loving creatures—fish, muskrats, ducks, and more—in wet years and wet seasons, as well as trees such as persimmons. In dry periods the lakes shrank, leaving grass- and shrub-covered expanses that the Spanish and French used for grazing livestock.

Water played a critical role in the history of Los Adaes. Today the area receives around 53 inches of rain annually, most of it falling in the late fall and early spring, and the summer and early fall being the driest time of the year. The Spanish settlers experienced periods of prolonged wet conditions as well as droughts, both of which made crops fail. Because the Spanish typically traveled on horseback or on foot, flooding rivers were major obstacles that sometimes held up expeditions and supply trains for weeks and months. In contrast, the French and the Indians used dugout canoes extensively. The Red River is the closest major water route to Los Adaes, and lies thirteen miles to the east. The closest perennial stream is Bayou DuPont, which drains the lower terrain east of the site and once entered Spanish Lake five miles north of Los Adaes.

|

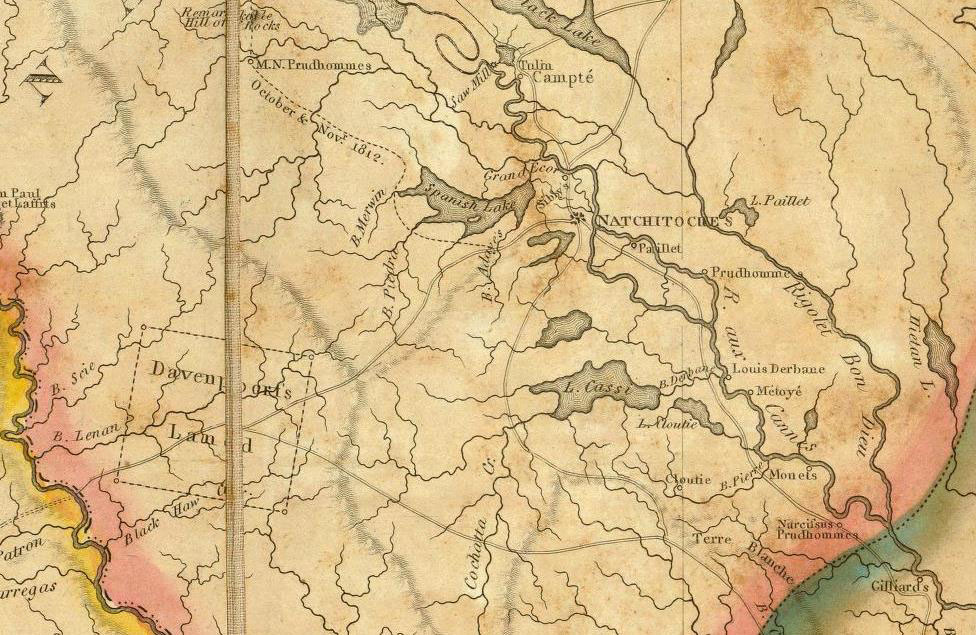

Detail of 1816 map by William Darby showing the Los Adaes region. The location of the abandoned Spanish presidio would not have been known to Darby, but the map depicts Spanish Lake fed by Bayou Adaye's, which is probably the drainage flowing just west of the site near the modern town of Robeline. The road shown leading west from Natchitoches is essentially the route of the Camino Real. Note the shaded upland ridge line paralleling this road. David Rumsey Map Collection.  |

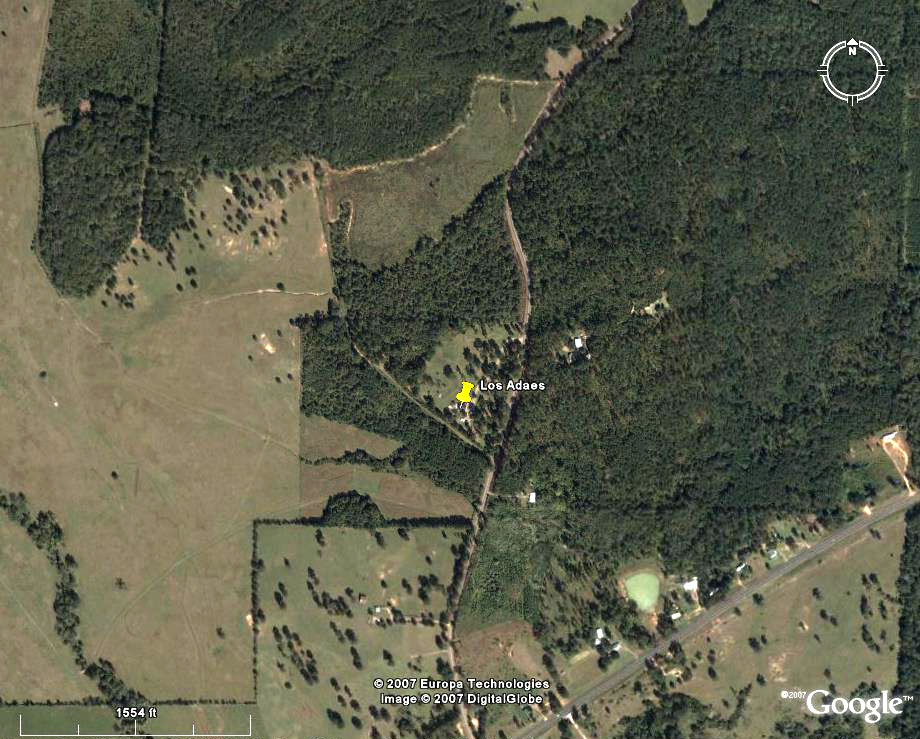

Google Earth image of Los Adaes area. The yellow pin is on the visitor center. Mission Hill, two-thirds of which is wooded, is visible as a half-moon shaped area to the lower left of the visitor center.  |

Google Earth image of the Los Adaes presidio area. The yellow pin is on the visitor center. Just above the buildings the eastern bastion and presidio outlines are clearly visible with darker grass.  |

Mission Hill in the early spring when redbud trees are blooming. View from presidio area.  |

Low-lying "plains" between Mission Hill (to left) and presidio (to right). In this 1986 photo, the "spring-fed branch" is visible as a slight depression darkened by grass killed by standing water after rains.  |

Spanish Lake lowlands about five miles northeast of Los Adaes. Today the area is drained pastureland. In the 18th century it was a large shallow lake which contracted and expanded seasonally. Photo by Steve Black  |

Barry Brake, a backswamp area north of Natchitoches, Louisiana, along the western edge of the floodplain of Red River. Many backswamp features in this area were formed by abandoned river channels. Prior to being razed for timber or cleared for pasture in the historic era, such swamps were rich ecological zones dominated by bald cypress and tupelo (water gum) trees that provided habitat for many animals, birds, and fish. Photo by Jeff Girard.  |

|