El Camino Real de los Tejas, or the Royal Road to the land of the Tejas Indians, was the name given to the eighteenth-century transportation corridor which connected the easternmost portions of the Province of Texas to the seat of Spanish royal authority in New Spain—Mexico City. In fact, any road that made a connection to a focal point near the edge of the Spanish borderlands was called a royal road, and as a result there was more than one royal road. Another notable example is El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro, the road from Mexico City to Santa Fe.

Unlike modern highways, the royal road was not a single line across the landscape, but rather a corridor within which there were various transportation features – such as main trails, secondary trails, bypasses, river crossings, and stopping places. Designated a National Historic Trail in 2004, El Camino Real de los Tejas once connected Spanish missions and posts, from Mexico City to Los Adaes, the 18th century provincial capital of Texas. Early Spanish explorers and expeditions followed established Indian trails and trade routes which formed the backbone of the royal road. Through time new trails and alternative routes were added, creating a net-like transportation corridor. As expressed on the National Park Service's El Camino Real de los Tejas web page, “the road’s development had irreversible impacts on the native people of Texas and Louisiana. It linked unconnected cultural and linguistic groups, and served as an agent for cultural diffusion, biological exchange, and communication.”

In the piney woods of East Texas, James Corbin and Jeff Williams rank as the primary researchers of the Camino Real. Corbin published in the groundbreaking volume edited by Al McGraw, John Clark, and Elizabeth Robbins entitled, A Texas Legacy: The Old San Antonio Road and the Caminos Reales, A Tricentennial History, 1691-1991. Williams’ 2007 master’s thesis on the subject stands as the most comprehensive work on the subject to date. In spring 2008, Williams identified a swale at Mission Dolores, which makes Mission Dolores the third public area in Texas which has a remnant of El Camino Real de los Tejas that visitors can experience firsthand—the other sites being Mission Tejas State Park and Caddo Mounds State Historic Site.

The swale or rut discovered at Mission Dolores in 2008 is a lingering physical trace of an old road that was created by many travelers over a long period of time. Worn into the ground, the swale is a shallow-to-deep U shaped linear depression created by heavy carts or wagons pulled by draft animals like oxen or mules. The swale at Mission Dolores lines up with Feature 65 discovered by Corbin in 1978, which he identified as a portion of the Camino Real based on land survey research that puts the feature in the correct location and by it being a shallow flat-bottomed depression. Swales from the Camino Real have been located and identified in several other places within the City of San Augustine as well as in surrounding counties. The old road, with many segments yet to be discovered, has left its imprint from the passage of countless travelers.

Numerous expeditions passed through Mission Dolores while traveling along El Camino de los Tejas between 1721 and 1773. The major expeditions are well documented and have been summarized by William C. Foster’s Spanish Expeditions into Texas, 1689-1768, but the accounts of unofficial travelers have far less documentation. One exception is the account of a young Frenchman named Pierre Marie François de Pagés, who passed through Mission Dolores several times in 1768 as he went back and forth between Los Adaes and the mission for the Nacogdoches as part of his trip around the world.

The narrative of Pagés’ trip was published in English in an enlarged three volume version in 1793. His comments are a firsthand account of what travel was like in 18th century Texas. Upon his arrival at Los Adaes, the governor was said to be at Mission Guadalupe for the Nacogdoches Indians. Pagés traveled with a guide to Mission Guadalupe, passing through Mission Dolores, and when he realized that no provisions were to be had in Mission Guadalupe, he returned to Adaes to procure them. Pagés traveled alone back to Los Adaes—something not recommended in those days. On the second day of this trip—probably somewhere between the Attoyac River and Mission Dolores—Pagés had two encounters with the local Indians. Starting the second day of this trip before sunrise, Pagés lost the trail and almost walked into an Indian village.

I wandered into a beaten path, which led directly to a savage village; happily, however, I recognized it through the trees by the round and conical form of their huts; and, in all probability, I owed my escape to Providence, and the obscurity of the morning; for had the savages chanced to be awake, presuming under the first impulse of surprise, that I came as a spy or robber, they would undoubtedly have fired upon me. – Pagés 1793:66

Later on that same day, Pagés encountered a group of Indians —probably Ais Indians—on the trail.

The same day I observed a party of natives before me, when that involuntary fear of them entertained by Europeans, which I had not been able to overcome, prompted me to skulk from the path, with a view to dine, as well as to avoid their company. The moment, however, I alighted from my mule, I was accosted by a couple of their women, who requested I would supply them with some Indian corn, and I very readily shared with them what little I had. But the reader may guess my surprise, when some time after they returned to testify their gratitude, by making me a present of cakes made of wild fruit. I afterwards fell in with men of the same village, from whom I received much kindness; they were at great pains to put me in the best path, and to instruct me what stages were most convenient for feeding my mule, as well as for my own accommodation. – Pagés 1793:66-67

It’s interesting that Pagés wrote more of his encounters with the Indians around Mission Dolores than the residents of Mission Dolores. All he says about Mission Dolores itself is that he passed through there. It appears that Pagés chose not to stay at Mission Dolores. He spent the night of the second day of his journey alone in the woods and when he awoke during the night to move his mule to another pasture, he found that his mule was gone.

What a dismal prospect now opened to my mind! I had lost my mule, was in the midst of an immense forest, without provisions, and without arms either to procure subsistence, or to defend my life against an enemy. I cast a melancholy look at my bear-skins and saddle, which served me for a bed and pillow; under the terror of losing myself in the woods, almost trembled at the thoughts of venturing forth in search of my companion. Necessity, however, at last prevailed over my fears; and collecting all my courage and presence of mind, after conjecturing from the moon’s situation the direction of the path, I rushed into the woods. Luckily I found my mule in the space of half an hour, grazing on the sloping bank of a rivulet, which afforded him good pasture; but by what means he was to be caught I knew not, and this excited new cause of disquietude. I can say truly, that here, as in other trying situations, my temper never forsook me; and after various fruitless efforts, I at length got hold of him.

– Pagés 1793:67-68.

|

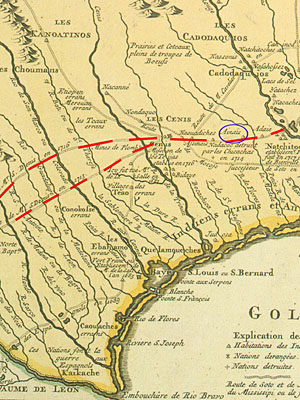

Portion of a colorized version of the famous Delisle map of 1718 to which dashed lines have been added to show several of the alternate routes that fell within the corridor that came to be known as El Camino Real de los Tejas. The location of the Ais villages near where Mission Dolores was built is circled in blue.  |

Jeff Williams walks along a swale near Mission Dolores thought to represent the road cut of El Camino Real de los Tejas.  |

A swale or rut is the remains of an old road that was created by large volumes of travel over a long period of time. Worn into the ground, the swale is a shallow-to-deep U shaped linear depression created by heavy carts or wagons pulled by draft animals like oxen or mules. Photograph by Jeff Williams.  |

The swale at Mission Dolores lines up with Feature 65 discovered by Corbin in 1978, which he identified as a portion of the Camino Real based on land survey research that puts the feature in the correct location and by it being a shallow flat-bottomed depression. Adapted from Corbin et al. 1980, Figure 65.  |

Cover of 1991 study that features a chapter by Jim Corbin on El Camino Real de los Tejas in East Texas. |

|