Father Margil had placed Mission Dolores in the middle of eight Ais settlements said to have been llocated within a three mile radius of the mission and inhabited by a total of 80 families. The Ais came to be proficient in the Spanish language and also in the use of French firearms, and for a short time in the 1750s, some families actually lived at Mission Dolores. For the most part, though, the Ais lived in their own settlements and would visit the mission to help with the crops. Occasional "hour of death" baptisms were performed on dying Ais by the priests of Mission Dolores. Apparently, the priests were reluctant to baptize Ais children because they were afraid that the children would not grow up leading a Christian life. It also appears that some of the Ais were afraid of the baptismal water, thinking that it was the cause of death since it was often administered just before death.

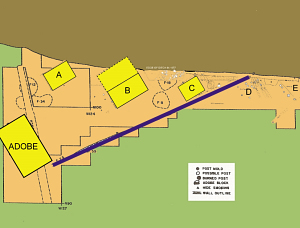

Two priests and one lay brother were assigned to Mission Dolores, along with two soldiers and their families. The buildings included a church and residences. Archaeological evidence suggests that one building may have been an adobe block structure, and others represent jacal type structures. The people of Mission Dolores grew corn, figs, garlic, onions and green vegetables of many kinds. A nearby ranch provided cattle, and cow bone fragments are abundant at Mission Dolores. Roughly 60% of the animal bone fragments are from European domesticates—59% are from cattle and 1% from sheep. Another 25% of the bone fragments are from deer and the last 15% are from fish, reptile and small mammals.

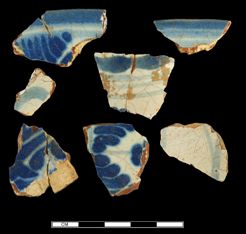

The French influence at Mission Dolores is undeniable in the archaeological record. The ratio of French to Spanish tin enameled earthenware is four to one. Fragments of French firearms have also been recovered. The French had a free trade policy with both the Spanish and the Indians, but the Spanish Crown forbade the trade of merchandise with the French (except food) and forbade the trade of guns and alcohol to the Indians. In 1766, one of the priests assigned to Mission Dolores testified that another priest who had been arrested for the possession of French trade goods was handling such goods to entice the Indians to come settle at his mission.

Indian pottery fragments dominate the manufactured goods recovered from Mission Dolores. It is likely than many of these fragments represent containers for Indian food stuffs, such as corn or bear fat, but table ware is also represented. Given the likelihood that few Ais actually lived at Mission Dolores, most of the aboriginal pottery must have been used by the mission’s Spanish inhabitants.

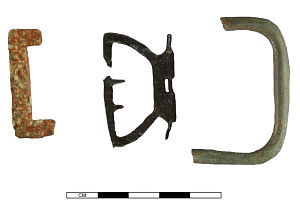

The European artifacts recovered from Mission Dolores give us glimpses into mission life including food preparation and service, military armament, clothing, religious items, and even music, as the following entries illustrate.

Preparing the Meals

Maize was a staple at the East Texas missions, and the mano and metate were standard food processing tools in Spanish Colonial households. The Nauha Indians of central Mexico ground their corn on rectangular shaped grinding stones called metlatl, which the Spanish interpreted as metate. The Spanish used their own term—mano—for the stone you held in your hand to grind against the metate. Mano means “hand” in Spanish. Several mano fragments made of volcanic tuff were recovered from Mission Dolores and were likely brought from Mexico. Similar grinding tools are still cherished by some of the old Spanish families living along the Texas-Louisiana border in the former eastern province of Spanish Tejas.

A chocolate pot handle represents a popular drink among the residents of the Spanish Colonial period habitations in East Texas. Chocolate is native to southern Mexico and Central America, and become consumed widely in Europe in colonial times after being introduced from the Americas. Chocolate appears in the account ledgers of the soldiers of Los Adaes, along with pilonsillo or brown sugar, suggesting that the Spanish were sweetening their chocolate.

Fragments of both iron and copper alloy containers have been recovered from Mission Dolores. These were probably used in cooking, although it is likely that Indian pottery vessels were also used in cooking, given the large quantity of aboriginal ceramics, and the great distance from Spanish markets.

|

|