Simulating Mission Dolores Today

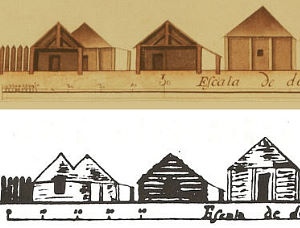

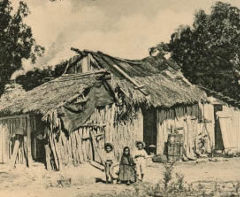

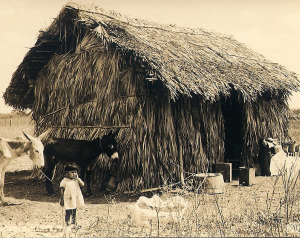

Model of Mission Dolores complex showing interior buildings with shingled roofs and finished exteriors, and an exterior jacal in the palisado style. Mission Dolores Museum.

|

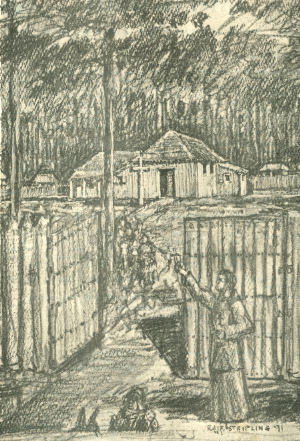

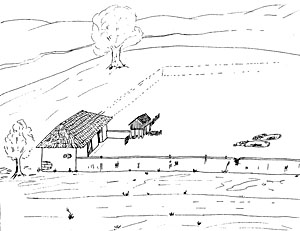

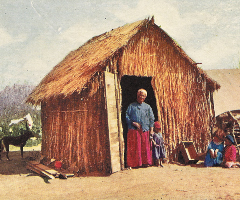

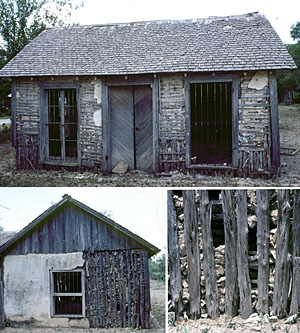

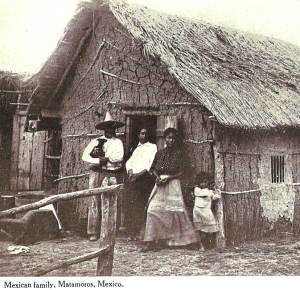

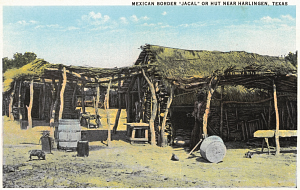

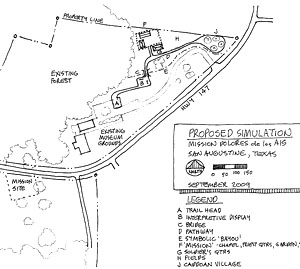

The desire for a replication of Mission Dolores is still the driving force behind activity at the mission interpretive complex today. Built in 1998, the complex includes a state-of-the-art museum and archaeology lab. Although the building of a replica of the mission was included in the master plan for the interpretive complex, the replica could not be constructed. Recall that for over forty years the mission location could not be verified. Once Corbin finally succeeded, he found that not enough of the mission survived to allow an accurate reconstruction or even replication of the mission complex. Too much remains unknowable. A renewed effort to build a replica of Mission Dolores was begun in 2007 by the San Augustine County Historical Society. The overall effort was coordinated by James Bruseth, who directs the Archeology Division of the Texas Historical Commission. The shovel testing survey project conducted by George Avery in 2008 was a direct result. Yet this work confirmed yet again that there was not enough surviving evidence to allow an accurate replica to be built. The ongoing project is focusing on the interpretative value of having a life-size, three-dimensional rendering of the mission complex. Basically, people need to have something tangible to see and interact with when they visit the mission. While we can not accurately reconstruct or replicate Mission Dolores, there is a feasible alternative. it is feasible to build a mission complex in another nearby location By combining the available information from excavations and historical research at Mission Dolores and Los Adaes with other sources, we can build an authentic three-dimensional rendering or "simulation" of the mission complex. A model for this simulation currently resides in the museum. Architect Mark Wolf is using his expertise in the research of Spanish Colonial vernacular architecture to spearhead the design phase of the Mission Dolores replica project. Other current research associated with Mission Dolores includes the work of Jeff Williams and Connie Hodges in locating and mapping segments of the Camino Real in the area. Both are students of Jim Corbin—or “Corbinites.” Another Corbinite, Carolyn Spears, Director of the Stone Fort Museum at SFA, has organized several workshops for teachers and heritage managers that have included a tour of Mission Dolores. Now that El Camino Real de los Tejas is an operational National Historic Trail, there may be funds available from the National Park Service for research projects along the trail. For instance, Connie Hodges of the SFA Center for Regional Heritage Research has conducted oral history interviews recently focusing on life and travel along the Camino Real de los Tejas from the Sabine River to the Angelina River as part of the National Park Service grant that funded this online exhibit. Simulation ProjectColonial Williamsburg in Virginia and New Salem Village in Illinois, among others, are examples of reconstruction as the goal for the development of public interpretive programs at archaeological sites. That is, do the archaeology and then reconstruct the buildings—post for post—just the way they were recorded by the archaeological investigations. Reconstruction as part of developing archaeological sites for public interpretation is now frowned upon as being too destructive of the remaining archaeological traces. ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) is very much against the reconstruction of archaeological sites on both a national and international level. But back in the 1970s, reconstruction was the goal for archaeological investigations at Mission Dolores that were sponsored by the San Augustine County Historical Society.. When the archaeological investigations revealed that much of the mission complex had been destroyed, the sad reality that the mission could not be faithfully reconstructed set in. This dawning realization was cause for much concern in the 1970s and 1980s. Happily, in 2008, a graduate student in the Historic Preservation program at the University of Texas—Erin Tyson—proposed a viable alternative idea—a “simulation.” That is, use the available archaeological and archival information for Mission Dolores, combined with relevant archaeological, archival, and ethnographic information from other Spanish Colonial period sites in Texas, and come up with a reasonable model of what the Mission Dolores complex might have looked like. The key would be to present the model to the public not as a reconstruction or replication, but rather as a simulation. The goal is to combine multiple lines of historical and archaeological evidence to be as authentic as possible. Authenticity, however, sometimes goes against prevailing notions of what structures in the past looked like. The initial interpretation of the Spanish Colonial period domestic structures in the region was clouded by the idea that many domestic structures built by Europeans long ago were log cabins or log houses. While domestic structures built by Anglo-Americans in the 1800s in Texas were indeed log cabins and log houses, this construction style was not practiced by either the Spanish or the French during the 18th century in this area. Nevertheless, a 1930s replication of Mission Tejas (west of Nacogdoches) was built in the log cabin style, and a Spanish map of Los Adaes (near Natchitoches) was altered to render the dwellings log cabin style. In contrast, a 1971 sketch of Mission Dolores by San Augustine architect Raiford Stripling correctly depicts the structures with vertical rather than horizontal lines. Such structures are referred to as jacales, thatched-roof huts with walls made of upright poles usually covered with mud (daub).

|

|