Looking west across site area toward

the Franklin Mountains in the distance. With only 8

inches of annual precipitation, the site environment

today supports semi-arid desert shrubs with little grass,

lots of mesquite, creosote bush in gravelly areas, and

some narrow-leaf yucca. Pueblos tend to be concentrated

near mountains where runoff could be used to water crops

and surface water would have been available for drinking.

The mountains and foothills supplied timbers for houses,

a variety of plant and animal foods, and raw materials

for chipped and ground stone artifacts.

|

Sgt. Richard Dillard and his daughter

working in Room 2. The drill sergeant at Ft. Bliss had

noticed the work at the pueblo while passing on Highway

54. Like many others he stopped, visited, asked questions,

and returned to help with work at the site. The Dillards

are one of many families who took part in the work.

|

Hal Siros uncovers a finely shaped

mortar and pestle set cached in pit of Room 15, one

of the pithouses found beneath the pueblo.

|

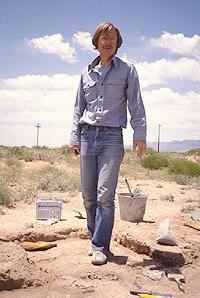

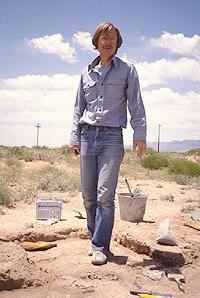

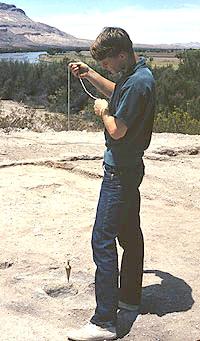

Site director Tom O'Laughlin at Firecracker Pueblo in

the mid 1980s. For 10 years O'Laughlin worked with members

of the El Paso Archaeological Society, university students,

and many other volunteers, including members of the Texas

Archeological Society to excavate the site. Photo by David

Guiffe. |

|

Firecracker Pueblo appeared to be a small and

unremarkable pueblo when it was first recorded in 1975. Next

to Highway 54 in northeast El Paso, Texas, 8 km south of the

Texas-New Mexico border, the leveling of sand dunes had revealed

the adobe walls of what was thought to be a pueblo of some

6 to 10 rooms. Between 1975 and 1979, additional grading of

the site area exposed more walls, dark soils, and a variety

of ceramic and stone artifacts. Temporary fireworks stands

placed on the site during this period gave the site its name.

Vandals began digging in several rooms, and the area became

part of an industrial park. Fearing greater damage or loss

of the site, formal excavations to document the site were

started in the summer of 1980. At the time, we had no idea—or

desire—that the Firecracker investigations would last

for ten years.

Volunteers led by archeologist Thomas C. O'Laughlin

provided the direction and work force for the project, and

literally hundreds participated in the excavation on weekends,

holidays, and, on occasion, for one or two weeks in the summer.

The youngest volunteer was 4; the oldest over 80. Many were

members of the El Paso Archaeological Society (EPAS), but

the location of the site next to a major highway lured numerous

passersby into lending assistance (see Public

Archeology). Television and newspaper coverage also stimulated

interest. Professors in a variety of disciplines from the

University of Texas at El Paso spent time at the site, as

did their students (sometimes for credit). In 1986, the Texas

Archeological Society held its field school at the site and

over 200 people participated in the eight-day event (see "Just

Barely in Texas").

The field investigations of Firecracker Pueblo

lasted 10 years in part because of the intermittent schedule

of an all-volunteer operation, but mainly because the site

proved larger and more complex than we first expected. As

we learned more about it, we saw opportunities to address

new questions and altered the strategy accordingly. Prior

to the investigation of this site, there had been no systematic

excavation of areas lying outside of pueblo rooms. In the

Jornada region, pueblo sites had been treated as if the pueblos

themselves were all that was important to study. At Firecracker,

we wanted to know what lay beyond the adobe walls—what

did the whole site look like? Therefore, we conducted systematic

and extensive excavations of extramural (outside-the-walls)

areas and found numerous and varied features, superimposed

structures, and considerable trash. Some findings were expected;

others were intriguing. Perhaps the most important discovery

was that of 17 pithouses from one or several shortterm occupations

immediately prior to the construction of the pueblo.

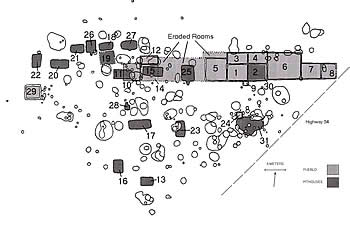

Site Map with Room Numbers

Most of the site maps used in this exhibit have

been simplified or altered for emphasis. This map shows the

room numbers assigned to both pueblo and pithouse rooms.

Sliding into Archeology

Tom O'Laughlin, the archeologist who led the

Firecracker investigations and the primary author of this

exhibit, became interested in archeology in a most unusual

way. As a child, he lived at White Sands Missile Range where

his father served in the Army. He remembers being intrigued

with scattered pieces of pottery and other strange objects

he found in his backyard. These, he was told, were very old

Indian artifacts. Then one day while playing baseball on a

sandy lot behind the school, a teammate slid into third base

a bit too enthusiastically. When the dust settled, bones were

visible in the freshly ploughed sand—human bones. O'Laughlin

returned to the sandy lot the next day and watched with fascination

as a tall lanky man carefully exposed what remained of the

burial.

As it turned out, the man was archeologist Larry

Hammack, then on loan to the Army from the Laboratory of Anthropology

at the Museum of New Mexico. He was there because the Commanding

General of White Sands was keenly interested in archeology.

With the Commander's encouragement, Hammack and off-duty military

personnel excavated a small El Paso phase pueblo on the base.

O'Laughlin visited the dig every chance he got, asking questions

and learning about what was being found. Others took him on

field trips and introduced him to rock art. He was hooked.

O'Laughlin joined the El Paso Archaeological Society in 1960

and has been a member ever since.

After his family moved to Las Cruces, he started

archeological projects on his own, recording sites in the

area. While still in high school he began giving presentations

and writing papers, efforts that earned him an award from

the New Mexico Archaeological Society. The summer he graduated

from high school he attended the University of New Mexico

field school at Taos and became acquainted with professional

archeologists who became his mentors and life-long friends.

His path was set.

In college he pursued biology and anthropology,

earning several biology degrees from New Mexico State University

and a Masters in Anthropology from the University of New Mexico.

Throughout he worked on archeological projects every chance

he got, first as a volunteer and then as a paid archeologist.

Some of his early projects included Fremont sites in Utah

through Jesse Jennings, the Anasazi Origins Project directed

by Cynthia Irwin-Williams in central New Mexico, and excavations

at Fort Fillmore directed by John Wilson of the Laboratory

of Anthropology of the Museum of New Mexico.

Today O'Laughlin is the Assistant Director of

the Albuquerque Museum. He has been long associated with natural

history and history museums. While running the Firecracker

excavations, he served as chief curator at the El Paso Centennial

Museum and Director of the Wilderness Park Museum. He has

also done contract archeology, taught at UT El Paso, and co-directed

the Jornada Anthropological Research Association.

Throughout his career O'Laughlin has maintained

a close relationship with avocational archeologists. He is

a longtime member of not only the El Paso Archaeological Society

but also TAS, the New Mexico Archaeological Society, and the

Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society. Presently,

he is a Trustee for the New Mexico Archaeological Society.

Firecracker Pueblo lies at the heart of O'Laughlin's

geographical area of interest—central to southern New

Mexico and west Texas, with extensions into Mexico. Although

a specialist in the pueblo period, he has worked on many other

kinds of sites. For example, he worked with J. Charles Kelley

at Alta Vista in Zacatecas, Mexico, a major ceremonial center

of the Chalchihuites Culture about A.D. 500. Currently (2001),

he is working with Mike Adler and Michael Bletzer of Southern

Methodist University on the investigation of Piro pueblos

near Socorro, New Mexico.

|

Looking west across the first four

rooms of pueblo to be excavated.

Click images to enlarge

|

Members of the El Paso Archaeological

Society admiring a job well done at the end of the day.

In the foreground is a nice pueblo room.

|

Room 22, excavated by Rob Vantil's

TAS crew, is a deep pithouse thought to have been used

for storage because of the absence of the usual floor

features. Trash had been dumped in this room by the

later occupants of the pueblo.

|

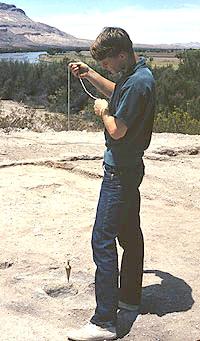

Tom O'Laughlin helps map Robledo

Mountain Pueblo near Las Cruces, New Mexico, while still

a teenager. His precocious archeological work as a high

school student earned him an award from the New Mexico

Archaeological Society and set his career path. Photo

by Dave John.

|

|