Coiled basketry impressions in baked

clay.

|

Chart showing the radiocarbon assays

from Firecracker. For each assay, the black bars show

the 67% probability age ranges while the open rectangles

show the full probability range.

|

Egg shells and animal bone from fill

of Room 25, a pithouse beneath the pueblo room block

which was partially filled with trash by the pueblo

occupants.

|

|

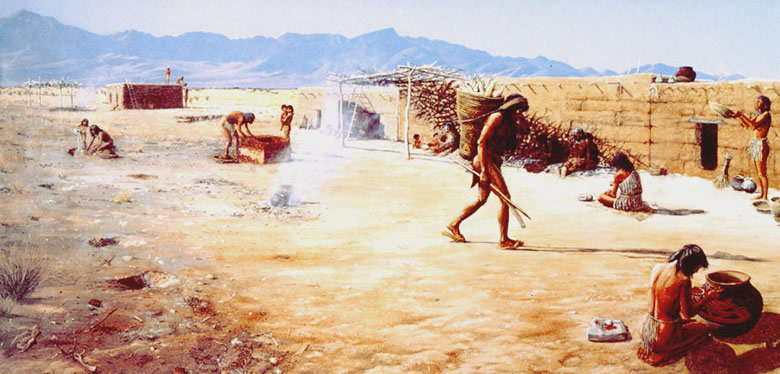

Firecracker Pueblo's setting in the northern

Chihuahuan Desert and its relatively recent date—less

than 600 years old—allowed the survival of many organic

remains: burned and unburned wood, grass, stalks, wild and

cultivated seeds, animal bones, and various other items. These

organic remains have provided important information on the

diet and lifestyle, construction methods, and the age of the

site. The construction techniques are discussed in the Pueblo

and Pithouses sections.

Here we concentrate on the age of the site and its economy.

The Age of the Site

From the pottery types present at the site and

other characteristics, we knew that Firecracker Pueblo was

a fairly late site. The generally accepted age of the El Paso

phase was A.D. 1200-1400 and it was expected that radiocarbon

assays would place the site near the end of that period. Instead,

most of the dates fell within the fifteenth century.

In the Southwest, wood is not the preferred

material for radiocarbon dating because of the "old wood"

problem. Simply stated, the dry conditions mean that wood

can last several hundred years or more in some circumstances,

particularly at residential sites where building materials

are often reused. Thus, dating old wood provides an estimate

of when the tree was felled, not when the wood was last used.

To avoid this problem, only seasonally produced materials

were dated—short-lived plants and plant parts—including

corn, beans, grass, and agave stalks.

Eight radiocarbon assays were obtained as shown

in the chart. As is often the case when there are multiple

radiocarbon dates, some are in agreement with one another

and other dating methods and some are not. In this instance

there are two dates from Room 20 which are significantly different

from one another and from the other dates. The older of these

two dates would suggest occupation between the eighth and

tenth centuries and is much too early as it falls long before

the generally accepted beginning of the El Paso phase at about

A.D. 1200. The second date for this room spans the twelfth

and thirteenth centuries, is within the generally accepted

date of the El Paso phase, but is still significantly younger

than the other radiocarbon dates. This structure is one of

the pithouses in the larger group of east-west oriented pithouses.

The reason the dates from this structure fall considerably

younger than the other radiocarbon dates is uncertain, but

may well be because of contamination. This is the only structure

on which recent trash had been deposited and mixed with the

room fill. Among the debris were the remains of a calf, fireworks

debris, and oil deposits.

There are two radiocarbon dates from Room 13,

a pithouse in the group of four pithouses in the southern

part of the site. The 95% probability range on the average

of these two dates is A.D. 1401-1450, suggesting that the

pithouse occupation occurred during the first half of the

fifteenth century.

Turning to the pueblo, there are four radiocarbon

assays. Rooms 2 and 4 are part of the initial or core group

of four rooms of the pueblo. Feature 140 is a pit cut into

the pithouse (Room 25) that is beneath rooms of the western

part of the pueblo, and Feature 55 is a pit associated with

the pueblo occupation and beneath the last rooms at the west

end of the pueblo. The radiocarbon dates from these rooms

and features are not significantly different from one another

and have a 95% probability range of A.D. 1429-1491, perhaps

suggesting a slightly later occupation than that of the pithouses.

Except for the dates from Room 20, radiocarbon

dates from Firecracker Pueblo are not, in statistical terms,

significantly different from one another. The six remaining

dates have a combined 95% probability range of A.D. 1423-1473.

The radiocarbon dates from Firecracker are important

because they provide the first hard evidence that the El Paso

phase flourished in the fifteenth century. In fact, these

dates narrow the gap between the collapse of the pueblo system

in the Jornada region and the first Spanish entrada in the

late sixteenth century. When the Spanish entered the El Paso

area, they found hunters and gatherers who apparently did

not make pottery and grow corn. These Manso Indians may or

may not be related to the earlier peoples in the area.

Food Remains

The food remains found at the site are informative

for several reasons. First they show that the inhabitants

of Firecracker were ranging rather widely and making use of

many plants and a fair number of animals. The bones from the

site are mostly those of rabbits, jackrabbit and cottontail,

with a few small birds, rodents, snakes, and lizards. In addition

to local small game, an occasional deer or antelope was killed

elsewhere, field dressed and butchered—only meat bones

and a few bones useful for tools were brought back to the

site. Animal bones were much less common than plant remains.

Among the identified plant remains that are

probably food items or residue are corn cobs and kernels,

common and tepary beans, the rinds of cucurbits (squash) and

gourds, amaranth seeds, purslane seeds, mesquite seeds and

pods, tornillo pods, yucca leaves, agave leaves, sotol leaves,

datil seeds, prickly pear seeds, and pinyon nuts. A large

number of flotation samples was analyzed from floors, hearths,

room fill. Samples of the fill from many of outside features

were analyzed. This study is the only analysis of this sort

for a pueblo site and the largest and best-defined analysis

for any El Paso phase site. The native plant species identified

at Firecracker parallel wild food species reported for the

Mescalero Apache of this region.

This chart

shows the relative frequency of different kinds of plants

in the 128 flotation samples that were analyzed from Firecracker.

One of the most significant findings is

the widespread occurrence of both corn cobs and corn kernels

in samples from many pueblo and pithouse contexts. This shows

a heavy reliance upon corn and probably other cultigens. Sites

from earlier periods in the region have yielded negligible

amounts of corn and very low percentages of flotation samples

with corn. Some have suggested that the reliance of El Paso

phase peoples on corn may have contributed to the demise of

their culture.

|

Students collecting flotation samples

from the fill of one of the pithouses. The analysis

of many such samples from Firecracker Pueblo provided

a great deal of very useful information about what people

were eating and how they used the landscape.

Click images to enlarge

|

Charred corn kernels and beans in

fill of Room 13, the southernmost pithouse at Firecracker.

Most of the abandoned pithouses (or the depressions

they left) were filled with refuse during the pueblo

occupation.

|

Exposing a burned corn cob on the

floor of Room 20, one of the pithouses due west from

the Firecracker pueblo.

|

This chart shows the relative frequency

of different kinds of plants in the 128 flotation samples

that were analyzed from Firecracker.

|

|