Scallorn arrow points from the Harrell site. Small but

deadly, arrow points such as these were found amid the

bones of several individuals and were very likely the

cause of their death. Photo by Milton Bell.

Click images to enlarge

|

|

In contrast to the sweeping warfare implied in the

evidence from the desert Southwest, most of the violent

prehistoric deaths in the southern Plains, including

Texas, appear to be the result of relatively small-scale

raids.

|

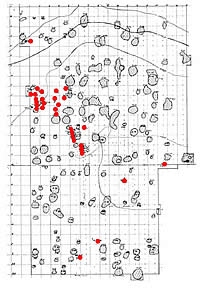

Map of burials at Harrell Cemetery,

showing depths and arrangement of some of the graves.

Although analysts recorded the remains of 32 individuals,

many skeletons were weathered, disarticulated, and incomplete.In

some graves, body parts of several individuals were

intermingled. Adapted from field drawings; Fox 1938,

TARL Archives.

|

Several feet to the southeast of

the mass burials 19-23, the burial of an adult female

(burial 26) was found. She had been placed within a

stone cist, her legs extended and upper torso folded

over. A bone awl was discovered near her head. Adapted

from field drawings; Fox 1938, TARL Archives.

|

|

On removing the bones, in the earth below were skeleton

hands—seemingly Burial 23 clasped the hand of Burial

22. George Fox, 1938.

|

Bones of parts of some individuals

were found mixed within the skeletal remains of others,

as in this grave holding burial 4 and a skull fragment

of burial 15. Drawing from Fox, 1938; TARL Archives.

|

Burials of three individuals were

found in close proximity, as shown in this drawing.

The compact arrangement of bones at bottom left is termed

a "bundle burial." The remains of that individual

likely had been bundled into a mat or covering and carried

to the cemetery from another location (the inset box

shows the burial after excavators removed the top bone,

revealing the skull).

|

|

How the mandibles, or jawbones, of the dead were

treated at the Harrell site indicated a more ritualized

pattern, clearly not a phenomenon of weathering or nature.

|

One of the hundreds of Cranial Measurement

and Observation data cards completed by Marcus Goldstein,

on file at TARL Archives.

|

A cache of mussel shells was found to the southwest

of burial 11 and near hearth 4. More than likely, they

were put aside.

|

Burial 30, another possible reburial

or "bundle burial". Drawing from Fox, 1938;

TARL Archives.

|

|

Violence was clearly afoot in prehistoric Texas

and neighboring regions some 1100 years ago and for centuries

thereafter. We don't fully understand the nature of the conflicts,

the triggering causes, or what carried the hostile impulse

across the southern Plains and far south into central and

coastal Texas. What we do know about this seemingly abrupt

behavioral shift comes chiefly from graves. In small cemeteries

of this time period, archeologists have found widespread evidence

of killing and tell-tale evidence of the instrument of death—arrows

tipped with small stone points—within the graves or even

embedded in the skeletal remains. Some skeletons show more

horrifying signs of violence—crushed skulls, decapitation,

and missing limbs. Taken together, this evidence shows that

during a three- or four-century span between about A.D. 900

and 1200-1300 killing and violence were widespread across

prehistoric Texas, a pattern that is also seen in the Southwest

in the A.D. 1200s and 1300s.

While humans have been killing one another throughout

recorded history and probably the entire span of prehistory,

direct evidence of violence is not seen at most Native American

sites in Texas. Aside from burned houses, which may or may

not have been intentionally set afire in anger, the only way

we can spot violence in the archeological record is through

studying human remains. Analyses of human remains found in

other areas of Texas, especially in the central coastal plains,

suggest that violence began to increase during Late Archaic

times about 2000-3000 years ago. While we will never know

what triggered individual episodes, increasing violence is

generally thought to reflect increasing competition for resources

brought about by population increase sometimes coupled with

deteriorating climatic conditions that forced people to intrude

into the territories of others. This is a plausible big-picture

explanation for what happened in the southern Plains in Late

Prehistoric times.

One of the most obvious changes that distinguishes

the Late Prehistoric way of life from the longstanding, earlier

Archaic pattern is a change in weaponry systems, from the

ancient spear-throwing device called an atlatl, to the bow

and arrow. Researchers believe this transition occurred gradually,

beginning with the "self" or simple bow (not recurved),

and that hunting peoples may have used both types of weapons

for some period of time. While Plains Indians apparently adopted

the bow and arrow well before the time of Christ, south of

the Red River the transition to the bow and arrow did not

occur until after A.D. 500. By the 1200s a more powerful

type of bow, the recurved bow, began to be used. But other

lifeway changes were probably more fundamental. The introduction

of pottery making allowed people to more easily create containers

and cooking vessels that could be exposed directly to fire,

thus changing (and improving) the way certain foods were prepared.

Even more important was the spread of agriculture, which gradually

allowed (or forced) people to stay in one place for longer

periods.

These changes were neither simultaneous nor

uniform across the southern Plains. But as the societies were

transformed from old ways of life to new, violence became

widespread, particularly during the period between about A.D.

900 and 1300. At Southwestern pueblos, there is indication

of all-out warfare or large-scale killing during the A.D.

1200s and 1300s. Archeologists in New Mexico and Arizona have

studied the ruins of large defensively fortified pueblos that

had been burned to the ground. At pueblo sites such as Techado

Springs in west-central New Mexico, there were piles of unburied

skeletons—many of them young women—apparently laying

as they fell during an attack or massacre hundreds of years

ago. In some Southwest sites, victims had been scalped, and

in others, body parts had been taken, perhaps as war trophies.

Across the southern Plains, the scale of violence

that occured during this time may have been more extreme than

archeologists previously thought. Archeologist Doug Boyd believes

there is ample evidence of devastating raids and attacks,

mutilations, and the taking of body parts as trophies in the

burial data. Although Boyd notes that southern Plains populations

may have been lower than in the Pueblo world, "intertribal

warfare was every bit as important and destructive."

Arrow Points among the Graves

At the Harrell site, the signs of violence were

unmistakable. In the small cemetery overlooking the Brazos

River, skeletons bearing signs of arrow wounds (or with points

lying nearby) were found within three or possibly four mass

graves. According to the very cautious field analyst's description,

arrow points in one of the mass burials were found "in

such positions as to suggest death from wounds." His

notes continue:

The skeleton of B19 had an arrowpoint lying

between the ulna and radius of the right arm and a second

point lay between the ribs. In the section of the backbone,

B-20 had a point protruding from the spinal column; it entered

from the left side, slightly forward of the spine and when

found, protruded from the back at a slight angle downward.

Perhaps the group burials, or mass graves, were

a hasty means of interment of several individuals who had

been killed in a conflict with outsiders. But, in haste or

not, the care shown for the dead is evident in how some of

the graves were arranged. In the largest group interment (shown

in the top photo, burials 19-23), two young men, their bodies

flexed, had been arranged to face a small child who lay between

them (burials 21-23). One of the adults—his pelvis pierced

by an arrow tip—appeared to clasp the hand of the child who,

archeologists noted, had a badly crushed skull. Another two

individuals, also victims of arrow wounds, were laid close

together in "spoon fashion," their knees drawn up

and almost interlocked. Finally, the entire grave had been

covered over with large limestone slabs, grinding slabs, and

smaller rocks.

Nearby, a second slab-covered grave (burials

27-29) held the incomplete remains of three individuals who

had been placed in the grave in similarly close fashion. Investigators

discovered an arrow point lying roughly in the area of what

would be the central man's lung or spine area, or possibly

the arm of the adjacent individual. Five other arrow points,

described as long, narrow, and thin (Scallorn type), and a

number of mussel shells, some used as tools, were found among

the skeletal remains of the other two individuals.

Another possible mass grave held the remains of perhaps six

individuals, their body parts layered atop one another in

a puzzling arrangement. One individual and a child (represented

primarily by skulls and leg bones) lay in a flexed position

beside another burial (represented by only a skull.) Resting

atop the thigh area of the two flexed skeletons were the leg

bones of another individual, and lying over the shoulder area

were two more sets of legs from yet other individuals. Although

some might speculate that the elements laying on top might

have been intrusive later burials, archeologist Fox noted

the alignments of the higher bones: "Either these bones

were placed with extreme care so as to have them in correct

position, or the limbs were yet in flesh when buried."

During excavations in the area (Excavation 3, which also included

the hearth field), investigators uncovered the remains of

32 individuals in all. Although the depths of the graves varied,

they all were within the upper deposits and apparently formed

a series dug in from the same surface, suggesting a burial

ground in continuous use by the same peoples. Few of the graves

intruded into one another—possible evidence that the

cemetery was a designated place and that the grave locations

were marked or well remembered. The tight grouping also suggests

that the graves are roughly contemporaneous and probably occurred

within a few generations.

Beyond that, however, the interments varied

radically: while 16 graves contained only one individual,

four bore the multiple interments discussed above. Another

grave—a likely reburial—was compressed into what

is termed a "bundle burial." It is likely that this

individual died elsewhere and the bones were brought back

to the Harrell site sometime thereafter. Other graves had

stone coverings, a few may even have been placed into a slab-line

enclosure or box-like cist. In one, an older woman (Burial

26) had been placed in an unusual position with legs extended

and upper body bent forward over the legs. The remains were

in poor condition and a number of elements were missing. Against

the top of the skull, excavators found what they termed a

bone awl (likely a hairpin). Although the grave was just southeast

of the mass burials numbered 19-23, it was several inches

higher than the others, and Fox was uncertain whether it was

related to the same burial event.

Archeologists studying the human remains at

the cemetery noted that the skeletons, as a group, were poorly

preserved; they could not determine whether this was due to

ordinary decomposition alone. There are several indications

that bodies or skeletons were dismembered or buried in an

already fragmented condition. In five, there was no sign of

the skull; two others contained merely skull fragments; one

had several teeth and a few bone fragments; several others

contained only sections of leg bones. In four, the skulls

had been carefully placed crown down, presumably after they

were no longer connected to the spine. Archeologist Fox wrote

that the inverted skulls were "so definitely in position

that the theory that a settling of the overlapping earth displaced

the skulls is untenable."

How the mandibles, or jawbones, of the dead

were treated at the Harrell site indicated a more ritualized

pattern, clearly not a phenomenon of weathering or nature.

In six graves, jawbones were absent even though the skull

was otherwise well preserved; in several others the jaws had

been removed and placed in the grave separately. In another,

more bizarre instance, the lower mandible appeared to have

been turned around and set in place inside the skull.

Displacement and removal of mandibles in burials,

whether a ritual among the aggressors or the families of the

aggrieved, has been fairly widely documented in other cemetery

sites across the region. Based on absence of mandibles in

graves from the Abilene area and farther west, early avocational

archeologist Cyrus Ray speculated that the jaws might have

been "war trophies." There is evidence for this

type of practice in the East Texas area as well.

Enigmatic cut marks on several of the Harrell

skulls have raised the possibility that the individuals may

have been scalped. Both Drs. Michael Collins and Darrell Creel,

who briefly examined the specimens under less than ideal light,

found the marks possibly to be suggestive of scalping but

altogether inconclusive. A more-thorough examination is needed

to fully understand and interpret the condition of the skeletal

remains from the site.

Funerary Objects

Throughout the cemetery, there were only scant

signs of what archeologists term "offerings" or

funerary objects, the special items sometimes placed with

the dead. Even then, the investigators could not be sure whether

the items had been worn by the individual, were embedded in

the body, or were laid into the grave with the body. As lead

investigator Fox describes their placement:

The grave offerings were very few; but with

three exceptions, doubt is entertained as to their being purposely

interred with the body. Within one grave, a bone awl stood

against a skull. In another, a small scraper lay beneath the

pelvic bone. In a third, two points, well made, were close

to an arm bone, in such a position as to indicate the two

arrows buried with the dead.

And further:

A bone bead was beneath the central portion of one grave

with two mussel shells, nested, not far away… In another

grave, about 12 inches from the bones, a mussel shell was

erect in the clay, standing on its pointed end. In yet another,

the mussel shell was set on edge….

At the north end of the cemetery, Fox recorded a number of

possible post-hole stains in the area of several graves with

very incomplete skeletal remains. The stains were in groups

or clusters; several appeared aligned in rough arcs. Although

neither Hughes nor Krieger addressed these features, it is

possible they may represent the supports for some sort of

mortuary structures or part of a larger building.

Aside from their obvious human interest, the

Harrell site graves are significant from a larger perspective.

In north Texas and further west across the southern Plains,

a number of sites bearing similarities to the Harrell cemetery

have been reported. Most of the graves seemed to be Late Prehistoric;

individuals usually were placed in the grave in a flexed position

and covered with stone. As at the Harrell site, some were

multiple graves in a single large grave, and some lacked mandibles

and other body parts. In rare cases, objects or grave "goods"

were added. Because of these similarities, we suspect that

the Harrell cemetery dates to roughly A.D. 1000-1300 in the

transitional period between the early part of the Late Prehistoric

period and the Plains Villager era which was the Harrell site's

heyday.

|

The small cemetery was located on the western

edge of the ridgetop habitation area-a maze of hearths,

pits, and refuse deposits accumulated over thousands of

years. Some evidence suggests, however, that the cemetery

may date to a more-limited time span somewhere between

A.D. 1000 to 1300. Map adapted from Fox, 1938; TARL Archives.

|

Partial grave covering of Burials 19-23. The limestone

slabs and grinding stones had been laid over portions

of the bodies of three adults and a child. Photo from

TARL Archives. |

A 1938 field drawing of a multiple

burial (27-29) records the close position of the individuals

and the arrow points which likely killed them. Adapted

from Fox; 1938, TARL Archives.

|

The individual in Burial 1 was found in a flexed

position with arms bent up and hands before the face.

A section of the lower jaw was found inside the skull.

Excavators found a flat stone "platform or hearth,"

with a small amount of ash, roughly 9 inches below the

lower part of the body. Drawing adapted from Fox, 1938;

TARL Archives. |

Remains of perhaps as many as seven individuals

were recorded in this burial. Drawing from Fox, 1938;

TARL Archives.

|

Physical anthropologist Marcus Goldstein,

shown in his laboratory at the University of Texas,

circa 1938. The cranial data he gathered provides information

on the sex, age, and condition of many of the skeletal

remains from sites such as Harrell. Photo from TARL

Archives.

|

The burial of an adult man (burial 25) who was

judged to be roughly 35 years old and appeared to be

"low-vaulted" to Marcus Goldstein, who performed

the cranial analysis. Drawing from Fox, 1938; TARL Archives.

|

Stones covering burial 25. Photo from TARL Archives.

|

To the east of the more defined cemetery

area, excavators found human remains in an apparent

refuse pit. Burial 32 consisted of little more than

an inverted skull, a displaced jaw bone, and leg bones

lying in the midst of shell and animal bones, a stone

slab, and what were recorded as dark spots in the soil.

One of the human leg bones was described in the records

as gnawed, suggesting the body had been left unburied

for some period of time—long enough for rodents

to disturb. Adapted from Fox, 1938; TARL Archives.

|

A pattern of small circular soil

stains in the cemetery was thought to represent postholes.

If so, the posts may have been supports for small mortuary

structures or for a larger building.

|

|