|

In this Section:

|

An unknown investigator points to

a lens of telltale burned rocks that alerted archeologists

to a buried midden, or camp refuse area. The stones

were uncovered as part of Excavation 1. Photo from TARL

archives.

|

Contour map of the Harrell site,

showing locations of the three excavation areas. Excavation

area 3 was on top of the third terrace, some 40 feet

above low water level. Map from Krieger, 1946.

|

Tools of the excavators. Shovels

and picks hang cleaned and ready for the next day's

work. Photo from TARL archives.

|

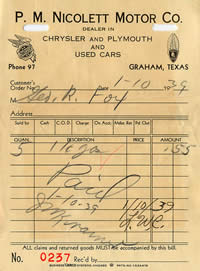

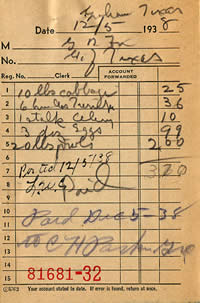

Gasoline

was cheap by today's standards, a mere $.11 per gallon,

but likely was not considered so in the depressed economic

conditions of the 1930s. Document from TARL Archives.

|

|

The WPA was both boon and bane to American archeology.

|

Manos and metates, implements used

for grinding corn, seeds, or nuts, were found among

the midden refuse deposits. Photo from TARL archives.

|

|

The systematic approach that A.T. Jackson laid out

was an important step forward for Texas archeology.

|

Workers and bosses wearing many hats

struggle for position as prehistoric occupation areas

are exposed at the Harrell site. Barns and outbuilding

of the farm and garden area on which Excavation 3 investigations

were located are in the background. Photo from TARL

archives.

|

Layer upon layer of silts and flood

deposits—creating the so-called "layer-cake"

stratigraphy—has been captured in this hand-colored

field profile of the bluff. Archeologists found only

sparse artifacts throughout, although they extended

to a depth of more than 20 feet. Profile by Raymond

Bland; TARL Archives.

|

A WPA worker keeps a watchful eye

on a pan heating over a twentieth-century "cooking

hearth." Photo from TARL Archives.

|

A typical hearth, formed of a single

layer of burned limestone fragments and measuring about

three or four feet across. Photo from TARL archives.

|

|

In hindsight, the WPA archeologists simply lacked

enough knowledge of geology and sedimentation to appreciate

what they had found in the second river terrace.

|

Prehistoric cooks constructed this

baking pit by digging a shallow basin and laying small

slabs against the sides. The pit may have seen service

for the cooking of roots or bulbs. Photo from TARL archives.

|

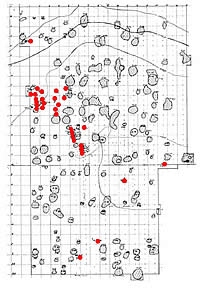

Map of hearths and burials (to the

west, or left, side) in Excavation 3. Burials have been

highlighted in red. Map adapted from Ray Bland drawing,

TARL Archives. (Click to enlarge image.)

|

One of the single interments in the

cemetery at the Harrell site. (See the Prehistoric

Cemetery section for more detail.) Drawing from

TARL Archives. |

Stratigraphic profiles of Excavation

3, showing the layer of dark midden earth (II) and underlying

reddish sandy clay (I). Note scattered burned rock features.

The unevenness of Stratum I may be due to the digging

in of pits for roasting ovens. Stratum III was a sterile,

windblown sand which sloped to the Brazos side. These

sands were blown up from the riverbed. Profile from

Krieger, 1946.

|

|

In the Fall of 1937, archeologist A.T. Jackson

of the University of Texas at Austin spotted a suspicious

line of broken limestone rocks eroding out of a cutbank on

the south side of the Brazos River just below where its Salt

and Clear Forks came together in southern Young County. Jackson

was searching for Indian campsites in the area that would

be inundated by Possum Kingdom Reservoir, then under construction.

Jackson rightly suspected that the stones marked an area were

prehistoric peoples had built cooking hearths.

He was intrigued because the fire-cracked (or

"burned") rocks were buried by 7 feet of mud and

sand left by countless floods along the sometimes mighty Brazos

River. Here, Jackson realized, was a perfect place for an

archeological excavation that might shed light on the unwritten

history of the region. The property where Jackson found the

deeply buried hearth rocks was part of the M.D. Harrell farm.

He soon obtained the landowner's permission to conduct a major

dig there the following year to search for deeply buried evidence

of prehistoric life.

Jackson's survey was a continuation of a state-wide

archeological survey program begun in the mid-1920s by Professor

James E. Pearce at the University of Texas. Pearce, sometimes

called the "father of Texas archeology," was a visionary

who worked tirelessly to establish an anthropology department

at the university and get the state-wide survey underway.

"Survey" to Pearce meant locating and digging important

archeological sites in different areas of Texas. Unfortunately,

his approach to archeological excavation was not methodical

and his early excavations sometimes were little more than

artifact mining operations.

Pearce apparently believed that by amassing

large artifact collections he would be able to understand

broad cultural patterns. Like many early archeologists, he

had a static view of prehistory and failed to understand that

many of the artifact collections he studied represented thousands

of years of cultural development. Jackson was Pearce's chief

assistant and a former newspaper reporter who quickly became

adept at archeology. He was naturally curious and skilled

at making do with whatever conditions he found himself in

as he traveled across Texas in search of places where important

archeological sites could be found.

In the 1920s, most of the work was concentrated

in the Austin area with brief forays in more distant areas

of the state. Pearce struggled to find adequate funding to

fulfill his vision of sampling the archeology of the entire

state. By the early 1930s the National Research Council of

the National Academy of Sciences had established a Committee

on State Archaeological Surveys to dole out small grants to

universities in different parts of the country so that information

could be salvaged from the areas scheduled to be flooded by

reservoirs. At the time, reservoirs were being planned and

built all across the country to prevent floods, improve water

supplies, and generate hydroelectricity. While such projects

were good for the country, they were also destroying many

cultural resources such as Indian campsites as well as early

historic settlements. To help lessen these losses, the federal

government instigated what would become a three-decade-long

program of "salvage archeology" that was formalized

after World War II.

WPA Archeology

In the 1930s the country was mired in the Great

Depression following the collapse of the stock market in 1929.

Money and jobs were scarce and unemployment ballooned. The

federal government stepped in with what became known as the

New Deal, a set of relief programs designed to get the country

back on its economic feet. One of the most successful was

the Works Progress Administration (WPA), a program that put

thousands of Americans back to work between 1935-1941. The

WPA guidelines called for "useful" projects that

would benefit the public and that could be executed immediately

with a high proportion of the total costs being labor. The

projects also had to be near areas where most of the unemployed

lived, rural Texas being a prime example.

The WPA was both boon and bane to American archeology.

Archeology, as it turned out, was a perfect fit for the WPA.

One or two trained archeologists could oversee the labor of

dozens of unskilled workers. Under the WPA program massive

excavations of unprecedented scale were carried out at hundreds

of archeological sites across the country between 1935-1941,

especially in the south and southeast where the unemployed

were concentrated.

In Texas, many of the projects were administered

through the University of Texas at Austin under Dr. J. Gilbert

McAllister, who took over from Pearce. Pearce died in 1938

soon after he was appointed as the first director of the Texas

Memorial Museum, the creation of which had consumed his latter

years. McAllister was a cultural anthropologist, not an archeologist,

but he proved to be a much better administrator than Pearce.

McAllister continued to rely on A.T. Jackson, but he also

began bringing in academically trained archeologists like

Alex D. Krieger and J. Charles Kelley. The WPA mandate allowed

the UT archeologists to carry out large-scale excavations

in many locales ranging from northeast Texas to central Texas.

In the case of the Harrell site and a series of terrace sites

along the Colorado River upstream from Austin, the make-work

goals were integrated with the fledgling reservoir salvage

efforts funded by the federal government.

A.T. Jackson served as Archeologist in Charge

of the WPA work at the planned Possum Kingdom Reservoir. He

assigned George R. Fox to supervise the WPA excavations there

beginning in the fall of 1938. Not much is known about Fox,

aside from the fact that he returned home to Michigan soon

after the WPA work ended at Possum Kingdom Reservoir was completed.

Fox does not appear to have been trained formally as an archeologist.

Regardless, his notes reveal an organized man who followed

Jackson's guidelines methodically. Jackson, in obvious reaction

to Pearce's lack of methodological rigor, produced a Manual

of Archaeological Field Work in 1937. Carbon copies of this

manuscript were used by the WPA archeologists under Jackson

as a basic guide to field methods. The systematic approach

that Jackson laid out was an important step forward for Texas

archeology.

Jackson's organizational plan for the work at

Harrell and other sites specified that each crew would "consist

of approximately forty-five laborers, three cooks, two clerks,

one draftsman, and an assistant archeologist" under a

"crew archeologist." Fox served as the project superintendent

or "crew archeologist." His assistant was the timekeeper

who kept track of the hours worked by the unskilled laborers.

The clerks typed the daily field notes and many forms, while

the draftsman was in charge of drawing maps and field sketches.

The men in skilled positions were paid at a higher rate and

were chosen because of their qualifications. All of the unskilled

laborers were selected from the "relief rolls" of

unemployed men from north Texas communities.

For a six-month period from the fall of 1938

through the spring of 1939, the M. D. Harrell farm became

a work camp. Barns and outbuildings were joined by a small

village of temporary shelters, clusters of canvas tents for

workers, and makeshift laboratory areas for artifact processing.

Crews wielding shovels and picks methodically excavated 5-x-5'

squares laid out in neat grid patterns in three areas on two

of the river terraces. The center of most of the attention

was to be the family garden plot, high above the other areas.

At the time, the archeologists recognized three

river terraces along the Brazos. The first and lowest was

the modern floodplain which was not present in the immediate

site area. Through time, the Brazos River was slowly carving

its channel southward and eroding the second terrace and creating

the cutbank that Jackson had first examined. The top of the

second terrace was about 22-25' above the normal level of

the river. Major floods could still reach the top of the second

terrace. Further back from the river was the third terrace,

which lay about 36-40' above river level and beyond the reach

of even the worst floods. Modern geological work has shown

that the upper Brazos and its tributaries has a complex set

of terraces that formed at different periods of times and

that have been reshaped by periods of erosion. The "third"

terrace in WPA terms, probably formed at least five to six

thousand years ago.

The "Great Midden"

Plan

map of the Great Midden, showing circular pits and hearths.

Field drawing drafted by Raymond Bland; TARL Archives.

Work began on the river edge of the second terrace

atop the bluff where Jackson had spotted the line of hearth

stones 7 feet below the surface. This terrace was being steadily

undercut by the two rivers, a process that exposed the hearth

stones and would have eventually destroyed all the buried

evidence. Excavation 1 uncovered what was termed the "Great

Midden," a rather grand title for what proved to be a

burned rock midden—a sizable accumulation of heat-fractured

rocks nearly 28 feet in diameter, but less than a foot thick.

Within the expanse of burned limestone and sandstone fragments

were three circular depressions—the remains of baking

or roasting pits-filled with ashes and charcoal and little

more.

Today archeologists would take a great deal

of interest in the burned rock midden at the Harrell site.

Unlike the burned rock middens characteristic of the Edwards

Plateau in central Texas, the "great midden" accumulated

on a terrace surface that was soon sealed by flood deposits.

Central Texas middens typically formed on stable surfaces

and sometimes grew to 6 feet or more in thickness and several

acres in extent. Often the traces of the baking pits responsible

for the burned rock accumulation are obliterated by the mass

of rock. In contrast, the burned rock midden at the Harrell

site is preserved in an "incipient" stage early

in its formation.

It is obvious that the "great midden" at Harrell

formed as the result of the use and reuse of the three baking

pits, which can be seen in the photographs and drawings. Based

on ethnographic accounts from many different areas of North

America and on modern experimental work, archeologists now

have a good understanding of the process known as earth oven

cooking. At the Harrell site, like countless other sites in

Texas, plant foods such as roots and bulbs (no animal bones

were found in the midden), were baked in layered arrangements

of heated rocks, green plants, food, and earth known as earth

ovens. The heated rocks held and slowly released stored energy

(heat), which caused the green plants (such as fresh-cut grass)

to give off steam, thus slowly baking the roots in moist low

heat. The green layers also kept the roots from burning and

separated the food from the earth layer. Additional layers

of heated rocks are sometimes added above the food layer.

Capping it all was a thick layer of earth that served as an

insulation layer to hold in the steamy heat.

Some earth ovens likely continued cooking for

as long as 24 hours or more, although the pits at the Harrell

site are relatively small and probably represent shorter cooking

episodes. Once the food was done, the earthen cap, upper rock

layer, and top layer of green plants were peeled back so the

food can be removed. Notice in the photographs how the rocks

are arrayed around the pits. Most of the scattered rocks represent

fire-cracked rocks from earlier ovens that must have been

cleaned out of the pits when fresh, intact rocks were added

at the start of each cooking episode.

While Fox and Jackson had a rudimentary understanding

of how the "great midden" formed, they were sorely

disappointed by the lack of artifacts and soon decided to

abandon excavations in this area of the site. First, however,

the crew cleaned back the bluff face and recorded 25 feet

of multi-colored alternating layers of sands, silts, and clays,

each reflecting a different period of deposition. They also

dug a trench beneath the burned rock midden in search of more

deeply buried artifacts. They were again disappointed by the

lack of what was then considered to be a worthwhile find-a

projectile point or formal stone tool. They did note the presence

of scattered flint chips, showing that prehistoric peoples

were in the area while many of the layers formed.

In hindsight, the WPA archeologists simply lacked

enough knowledge of geology and sedimentation to appreciate

what they had found in the second river terrace. Today the

terrace exposures they created would be carefully studied

by specialists trained in reading the depositional layers,

like those found along the Brazos. Instead of being disappointed

by the sparseness of the artifacts, a good modern archeologist

would realize that here was the opportunity to study brief

moments in prehistory that were sealed and protected from

mixing by the flood deposits. By obtaining radiocarbon samples

from different layers, a geologically minded archeologist

(or geoarcheologist) would be able to reconstruct the depositional

history of the river terrace and tie this to the archeological

finds. Hindsight, as they say, is 20/20.

Also on the second terrace, the WPA crews opened

up Excavation 2 around a gully area downstream from the first

excavation area, where large limestone slabs were eroding

out. Several hearths were uncovered, but the area was found

to be badly disturbed by the gully and was soon abandoned.

The remainder of the work was centered on Excavation

3, the high third terrace where the Harrell family's farmhouse

and barnyard had been. The house had burned a few years earlier

and the family had moved to Graham, but still maintained the

farm. Beneath the Harrell family's vegetable garden, the WPA

archeologists encountered a prehistoric cemetery along with

a quantity of burned rock cooking hearths and ovens.

Hearths and Burials: Exacavation 3

In Excavation 3, investigators uncovered an

enormous hearth field with well over a hundred cooking hearths

and a small prehistoric cemetery with some 32 human interments.

Crews dug to a depth of 5 feet over an area roughly 135 feet

long by 85 feet wide. They then dug down an additional 5 feet

in the western half, excavating, in all, almost 90,000 cubic

feet of soil. The terrace deposits had two main strata: the

top layer, a dark, organic-rich midden (refuse) deposit, contained

the great majority of the cultural material; underneath this,

roughly 5 feet below the surface, was a stratum of red, sandy

clay.

The midden varied from 2 ½ to nearly

6 feet in thickness and was made up of loose dark soil full

of ashes, charcoal, shell, and bone. The contact with the

lower, red clay layer, was described as highly irregular and

pockmarked by small depressions (areas of darker soil) which

Fox thought might be refuse pits. None, however, had a definite

pit shape or was found to contain concentrated debris. The

unevenness of the contact between the two layers added to

the difficulty in plotting the artifacts.

Unlike the so-called "great midden"

at the site, the midden in Excavation 3 was rich with cultural

debris and artifacts—chipped stone tools, projectile

points, pottery sherds, shell, animal bones, and other items

discarded by various peoples living at the site over time.

Archeologists call such deposits refuse or kitchen middens.

Within the midden layer, workers found many rock-lined pits

and circular arrangements of burned rocks of the sort commonly

known as hearths, although many probably functioned much like

the baking pits found within the "great midden."

These cooking hearths and ovens—more than 135 of them—were

scattered rather evenly throughout the upper deposit. Most

were constructed of limestone slabs likely gathered from the

hills along the valley margins less than a mile away. Some

hearths had been constructed within pits, depressions filled

with dark midden soil that extended into a red clay layer

below.

Most hearths were little more than circular

clusters of broken limestone slabs that appeared to rest on

a flat surface. Others were dish-shaped, or concave, rather

than flat, and obviously had been built within shallow pits

or basins. Another distinct hearth form was a slab-lined pit

with its bottom paved by flat stones encircled by upright

or angled slabs. Still other hearths were irregular, steeply

sloping arrangements of rock that probably represent slab-lined

pits that had been partially dismantled. Although some of

the hearths contained several layers of rock, most consisted

of a single layer of limestone fragments in an irregular circular

shape, measuring about 3 to 4 feet across. Amid the stones,

workers found the tell-tale remains of prehistoric cooking:

ash, bits of charcoal, burned and unburned animal bones, and

mussel shell fragments.

Burials were confined largely to the western

edge of the excavation area, a locale that must have been

specifically designated by prehistoric peoples as a cemetery

or burial ground. Only a few of the graves overlapped one

another, suggesting that the locations of the burials were

marked or known to those who placed the graves. Depths of

the graves varied from roughly 3 to 6 feet below the surface.

As described more fully in the section on the Cemetery,

interments were both in single as well as group graves.

|

The Harrell site, located not far

from Graham, Texas, at the confluence of the Clear Fork

and main Brazos rivers, was investigated during a survey

of the area threatened by the construction of Possum

Kingdom Reservoir. Although the site was not inundated

by the lake, it has been eroded over time by natural

undercutting of the two rivers. Map courtesy of the

University of Texas Map Collection.

Click images to enlarge

|

James E. Pearce, sometimes called

the father of Texas archeology, oversaw many of the

early Texas survey operations. Photo from TARL archives.

|

A small city of tents housed workers

during the six-months of investigations at the Harrell

site. Photo from TARL archives.

|

A

1938 grocery bill shows food purchases for the camp at

a time when a dozen eggs went for about $.33 and 20 pounds

of hog jowls for $2. Based on Fox's records, the weekly

menu showed little variation, with emphasis on root vegetables

and cabbage. Document from TARL Archives.

|

Burned rocks eroding out of a gully

bank proved to be a hearth and was uncovered further

in Excavation 2 operations. The Brazos river is visible

in the background. Photo from TARL archives.

|

Visitors at the Harrell site. In

the background (view to northwest), the juncture of

the Clear Fork and Brazos rivers can be seen. Photo

from TARL archives.

|

An unknown man "stands sentry"

as a WPA crew member uncovers another hearth. Photo

from TARL Archives.

|

Field recorders drew a number of

the features in the field, such as this hearth, shown

in cross-section, found roughly 5 feet below surface

near the red clay stratum. Drawing from Fox, 1939; TARL

Archives.

|

The "Great Midden" had

at least three circular pits within the mass of fire-cracked

rock containing ashes and charcoal bits but few artifacts.

Shown is the "north firepit." Photo from TARL

archives.

|

Constructed with stone slabs set

upright, this circular hearth had a layer of flat stones

at the base. During investigations, the hearth was "pedestalled,"

or isolated at its original level for further study

while the surrounding area was excavated. On the right

is one of several deep trenches dug to explore the site.

Photo from TARL archives.

|

This hearth was constructed mainly

of fragments of metates, or grinding slabs. Photo from

TARL archives.

|

Workers uncover more burned rock

features at the bottom of a deep excavation unit. More

than 90,000 cubic feet of dirt was removed to explore

the Harrell site. Photo from TARL archives.

|

Examining burned rock features in

Excavation 1. Note the three basin-shaped, stone-lined

pits in front of the kneeling figure (an unknown investigator).

The masses of small limestone rocks surrounding the

pits are evidence of the oven "renewal" process-prehistoric

cooks had raked out spent burned stones after they became

too small and fragmentary to be useful in earth oven

cooking. Photo from TARL archives.

|

|