Pioneer Texas archeologist Alex

Krieger defined the cultural pattern known as the Henrietta

focus, drawing heavily on evidence from the Harrell

site. Photo from TARL Archives.

Click images to enlarge

|

|

Reconstructing the history of the part of the Brazos

on which the Harrell site is located is like trying

to visualize a motion picture on the basis of a few

still photographs. Jack Hughes, 1942.

|

Arrowpoints, including several of

the expanding stem Scallorn points found in the burials.

|

|

Today we realize that the archeological evidence

from the Harrell site is much more complex than the

archeologists of the 1930s and 1940s recognized and

that some of its cultural debris accumulated long before

the Plains Villager era.

|

| |

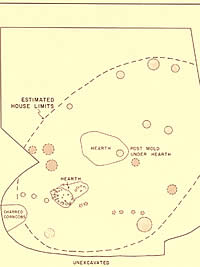

Fox recorded a series of soil stains

as possible post holes. Lacking further information,

we can only speculate as to the accuracy of the interpretation

and what they might represent. In this drawing, we have

superimposed the stains over the positions of the burials

in the area.

|

|

Stepping back in time, we see the transition between

Late Prehistoric I and Late Prehistoric II (the Plains

Village era) was a time of upheaval and extreme violence.

|

A 1938 field drawing of a multiple

burial (27-29) records the close position of the individuals

and the arrow points which likely killed them. Adapted

from Fox, 1938; TARL Archives.

|

The variety of dart points found

at the Harrell site suggests the site was used by prehistoric

peoples for several thousand years before the Plains

Village groups came to the spot. Drawing from Krieger,

1947.

|

Sherds of shell-tempered Nocona Plain

pottery are diagnostic of Plains Villager groups and

the Henrietta focus.

|

| |

Contour map of the Harrell site,

showing high terrace location of the main habitation

area investigated in Excavation 3. Map from TARL Archives.

|

|

From the present vantage point we can see that

the archeologists of the 1940s misunderstood several key aspects

of the Harrell site. The critical problem is that they did

not have any way to accurately gauge the age of the deposits.

Radiocarbon dating was not developed as a research tool until

the 1950s. And only in the last few decades have modern geological

methods been applied routinely in archeological investigations.

Without these two critical research tools, it is hardly surprising

that the Harrell site was seen by archeologist Alex Krieger

as representing a single culture which he called the Henrietta

Focus.

Alex Krieger was trying to make sense of extremely

broad cultural patterns and link the chronology or time line

of the poorly dated moundbuilding cultures of the southeastern

United States with that of the tree-ring-dated Puebloan cultures

of the southwest. He used the Harrell site and the Henrietta

focus to do just that by arguing that the Plains Villagers

of north Texas were contemporaneous with late Puebloan peoples

and late Caddoan groups. In a general sense, this view has

been borne out by a great deal of research over the last 65

years. But modern researchers have also learned many things

that enable us to reevaluate the dating of the Harrell site.

Krieger argued that the Henrietta Focus dated

to A.D. 1450-1650 based on the relative dates of several Southwestern

pottery sherds and at least one Caddo sherd that were found

at the Harrell site. From the fact that the site's distinctive

shell-tempered pottery (which he named Nocona Plain) was found

in both the midden and in the underlying red clay, Krieger

concluded that the entire 8- to 10-foot thick artifact-bearing

deposit in Excavation 3 could have formed in as little as

two hundred years, mainly as the result of the periodic addition

of flood deposits. He, like Jack Hughes, recognized that certain

of the dart points were more characteristic of central Texas,

where they were regarded as comparatively early artifact styles

that dated to the Archaic period before the introduction of

the bow and arrow. But Krieger assumed that the presence of

these styles at Harrell along with arrow points and pottery

in the same deposit meant that these dart point styles continued

to be used by latter peoples. In contrast, Hughes correctly

reasoned that earlier central-Texas-related peoples had lived

at the Harrell site before the later Plains-related peoples

who used the bow and arrow and made pottery. Hughes' views

were stated cautiously in his unpublished Master's thesis

and were soon overshadowed by Krieger's grand synthesis.

Today we have a much better understanding of

chronology. The earliest distinctive artifacts found at the

Harrell site are the beveled-stem Nolan dart points now known

to date to the Middle Archaic period about 4500-5000 years

ago (2500-3000 B.C.). Also found among the Harrell site's

artifacts are examples of Pedernales, Bulverde, Castroville,

Marcos, Ensor, Fairland and Darl dart points (among others),

indicating that the site was occupied intermittently during

much of the Late Archaic, roughly 1200 to 4500 years ago (2500

B.C. to A.D. 800).

Nonetheless, most of the artifacts at the Harrell

site do date to the Late Prehistoric era, between about A.D.

800 and A.D. 1500. According to Hughes, some 555 arrow points

were recovered from the site compared to only 81 dart points.

All of the almost 600 pottery sherds also date to the Late

Prehistoric, probably after A.D. 1200. In other words, the

site's major occupation period was after A.D. 800.

From the present perspective, we guess that

the third or high terrace where most of the Harrell site excavations

were carried out probably existed as a more or less stable

landform by about 5000 years ago (roughly 3000 B.C.). We further

surmise that during the subsequent 4500 years (from about

3000 B.C. to A.D. 1500) a maximum of five feet of sediment

accumulated on the terrace top. As Hughes realized, by far

the bulk of all the artifacts occurred in the upper five feet

in the dark midden soil as well as all 135 hearths and all

32 graves. The only things found deeper were relatively small

quantities of scattered artifacts, some of which were found

within the apparent pits that intruded into the underlying

red clay. Whereas Krieger assumed that river floods continued

to add sediment to the upper terrace while it was occupied,

we doubt this was the case to any significant degree during

the Late Prehistoric era. The midden layer is clearly what

archeologists today call an anthrosol (literally "man-soil").

That is to say that the refuse, artifacts, hearth rocks and

so on that people hauled to and left on the Harrell site were

mixed in with the existing soil resulting in a distinct cultural

layer.

We suspect that the Middle and Late Archaic

materials were buried fairly quickly and may have been neatly

stratified in a "layer-cake" fashion. However, after

A.D. 800 or so, the site was used more intensively by a series

of Late Prehistoric peoples, including the Plains Villagers

who were responsible for the bulk of the debris and midden

accumulation. There is obvious evidence that the Late Prehistoric

occupants were habitually digging holes—pits for hearths,

graves, and probably for houses and storage. These actions

intruded into and greatly disturbed the earlier (Archaic)

layers.

While no obvious evidence of houses or structures

was recognized, there were several tantalizing clues. Excavators

noticed two odd features in the southeast section of the excavation

block, in the area of Burial 31. One was an area of fire-burned

red clay with impressions of grass and twig marks. Fox noted

that it "appears a fireplace but looks like wattle work."

In the unit just north, he recorded an oval of cemented white

ashes with two cut depressions in the interior. Whether these

features pertained to a house (with wattle and twigs) with

an interior hearth is unknown; no further mention of the features

was made in subsequent analyses. At the north end of the cemetery,

Fox also recorded a number of possible post-hole stains in

the area of several graves holding very incomplete skeletal

remains. The stains were in groups or clusters, and several

appeared to align in rough arcs. These may represent the supports

for some sort of arbor-like mortuary structures similar to

those recognized at Zimms Complex sites in northwestern Oklahoma.

Nonetheless, houses and other types of structures

were almost certainly built at the Harrell site and probably

placed in shallow pits like those that have been documented

at many other Plains Villager sites. All this digging and

earth moving coupled with the continuous burrowing of rodents

(of which much evidence was seen) resulted in the site deposits

becoming badly mixed through time. While the overall trends

are clear—most of the dart points were more deeply buried

than most of the potsherds—the mixing makes it impossible

to neatly sort out the site into separate time periods. The

only things at the Harrell site that we can confidently date

are those that have been dated elsewhere.

Age of the Cemetery

Before attempting a trial reconstruction of

the human history of the Harrell site, we must raise a thorny

dating problem that cannot be satisfactorily resolved without

further research. That is the age of the cemetery. Krieger

and Hughes both assumed that the graves dated to the latest

and main period of site occupation. In broad terms this is

undoubtedly true: the graves are Late Prehistoric in age.

But today we recognize that the Late Prehistoric era spans

at least 700-800 years and probably 1,000 or more. The bow

and arrow may have been introduced into the southern and central

Plains before the time of Christ followed by the introduction

of cord-marked pottery during the first centuries A.D. These

technologies are the hallmarks of the Late Prehistoric era.

The early part of the Late Prehistoric (sometimes

called Late Prehistoric I), from perhaps A.D. 500 or so to

A.D. 1100-1300 is seen by most experts as a time of change

during which the hunting and gathering traditions that characterize

the long archaic era were gradually altered by the introduction

of a new weapon system (the bow and arrow), new storage and

cooking technology (pottery), and, even more importantly,

agriculture and semi-sedentary life. Some areas, such as most

of the Edwards Plateau in central Texas, continued to be occupied

by purely hunting and gathering cultures at the same time

that more-settled village life was becoming prevalent elsewhere.

By the later part of the Late Prehistoric (sometimes

called Late Prehistoric II), after A.D. 1200-1250, settled

villagers lived along virtually all of the river valleys of

the southern Plains. Most sites show evidence of corn farming

along with heavy reliance on buffalo hunting, a mixed economy

that sustained village life. This broad cultural tradition

is known as the Plains Villager horizon and it has been subdivided

into dozens of named phases, complexes, and foci reflecting

different local variations and changes through time over the

A.D. 1200-1500 span of the era. Most, but certainly not all,

of what Krieger included within his Henrietta focus dates

to this period.

Stepping back in time, we see the transition

between Late Prehistoric I and Late Prehistoric II (the Plains

Villager era) was a time of upheaval and extreme violence.

Skeletons riddled with arrow points, mass graves, trophy skulls,

and mutilated skeletons have now been documented at dozens

of sites ranging from the Texas Panhandle across north Texas

and western Oklahoma to central and southern Oklahoma and

southward well into central Texas. Broadly, most of these

sites seem to date to between A.D. 1000-1300 within the latter

part of what is generally considered to be Late Prehistoric

I. One of the most common arrow point types implicated in

this period of violence is the Scallorn type, which is also

the only arrow point type found with the graves at the Harrell

site.

The graves at the Harrell site also share several

other traits in common with Late Prehistoric I sites. These

include mass graves, cyst graves, and the removal of the lower

jaws and other forms of skeletal mutilation perhaps including

the heretofore unrecognized evidence of scalping. Because

of these similarities, we suspect that the cemetery at the

Harrell site dates prior to A.D. 1300 and prior to most of

the Plains Villager era including most of what Krieger included

within the Henrietta focus. It is possible, however, that

the cemetery dates to the beginning of the Plains Villager

occupation. If so, it may not be a coincidence that the Scallorn

point used by the aggressors is associated with older traditions

that lingered to the south in central Texas, while the villagers

represent a new tradition derived from the north.

The Prehistory of the Harrell Site

With all of the above in mind, here is our reinterpretation

of the prehistoric record at the Harrell site, concentrating

on the Late Prehistory. First and foremost we must emphasize

that without further research our educated guesses are just

that. Some of our inferences could be tested by further analysis

of the Harrell site collections. But what we really need are

more well-controlled excavations of prehistoric sites in north

Texas. Today we would use modern geological methods to help

choose sites that have better depositional contexts than that

of the Harrell site—less mixing and fewer repeated occupations.

Today we would collect charcoal samples and soil samples from

individual hearths. Today we would carefully study the animal

bones and the charred plant remains. And so on.

Based on today's knowledge, we infer that by

5,000 years ago (3,000 B.C.) hunters and gatherers were regularly

visiting the confluence of the Salt and Clear Forks of the

Brazos. In all likelihood, the area was a favored stopping

place much earlier, probably beginning in Paleoindian times,

but traces of such earlier occupations that may have existed

at the Harrell site were probably destroyed by the meandering

Brazos river. By 5,000 years ago the high terrace upon which

the bulk of the prehistoric record at the Harrell site accumulated

had stabilized and was above the ordinary flood level. The

near edge of the river itself was probably further north than

it is today based on the fact that the river is continuing

to swing southward.

During the Middle and Late Archaic or about

5,000 to 1,200 years ago (3000 B.C. to A.D. 800) hunting and

gathering groups who shared much in common with people living

further south in central Texas repeatedly stopped at the river

junction and stayed for short stays. They probably did many

different things at the site and in the area, but their habit

of baking roots and bulbs in earth ovens left the most obvious

archeological signatures—countless hearths and, in one

area near the river, a burned rock midden. The so-called "great

midden" is remarkable because it was covered by flood

deposits before it was used for very long, making it easy

to see the roasting pits that generated the spent fire-cracked

rocks that make up the midden. The age of the midden is unknown,

but it is probably associated with the Archaic period at the

site. The general absence of artifacts suggests that the "great

midden" was a special purpose cooking area that may have

been created on the lower river terrace to keep the area and

the activity separate from the main camp.

The main area of human habitation at the Harrell site was

atop the high terrace, even during Archaic times. We would

guess that most of the deeper hearths found there were Archaic

in age, based on the distribution of the dart points. Among

those hearths are a few that are comparable in size and shape

to the roasting pits found in the burned rock midden as well

as many smaller ones of various forms that must have been

used to cook different kinds of foods. There is little doubt

that Archaic life at the Harrell site was much more interesting

and involved than the simple inferences we draw here, but

further speculation serves little purpose.

By the early part of the Late Prehistoric, perhaps

around A.D. 800, the Harrell site had become a major habitation

site, a place where people regularly visited and stayed for

weeks or even longer. Over the next 700 years, a tremendous

quantity of cultural debris accumulated on the high terrace

overlooking the river confluence. Based on the large numbers

of basally and small side-notched triangular arrow points

and on the preponderance of shell-tempered pottery, we can

infer that most of the debris accumulated after A.D 1200.

That said, the cemetery could date somewhat earlier than this;

if so, the presence of a well-defined cemetery suggests that

people were already living there for extended periods of time.

In other words, village life at the Harrell site may have

begun prior to the Plains Villager period.

Some aspects of daily life were little different

from the Archaic era. Numerous hearths were found in the upper

few feet of the refuse midden including likely baking pits

and smaller hearths as well, several of which resemble hearths

found in the interior of houses at other Plains Villager sites.

But other things changed. The Plains Villagers at Harrell

were apparently farmers, but it is hard to gauge the relative

importance of agriculture. Although there were scapula hoes

and other possible farming implements, only a few corn cobs

were found. Judging from the relatively large numbers of bison

bones as well as the many beveled knives and hide scrapers,

buffalo hunting was very important during this period, perhaps

because more bison were present in the area.

Beveled knives such as

these from the Harrell site were used by Late Prehistoric

Plains groups who hunted buffalo.

Despite our misgivings about certain of Krieger's

assumptions, he was right to emphasize the Plains Villager

period at the Harrell site. The distinctive assemblage of

shell-tempered pottery, basally and side-notched triangular

arrow points (Harrell and Washita points), bison-scapula hoes,

handheld mussel tools, diamond beveled knives, hide scrapers,

and small drills has been found at other sites in north Texas.

While the Henrietta focus is still poorly understood, there

is little doubt that these materials are closely related to

other Plains Villager assemblages. In particular, there are

many shared similarities among Washita River phase sites along

the Washita and Canadian River valleys in south-central Oklahoma.

These are comparatively well dated to broadly A.D. 1200-1500

and perhaps mainly A.D. 1300-1450, according to recent syntheses

by Richard Drass.

The presence of extensive Plains Villager materials

at the Harrell site can probably be best explained as the

result of the movement of new people into the area, probably

from western or south-central Oklahoma. We cannot rule out

the possibility that local peoples simply adopted the trappings

of more-sophisticated neighboring groups, but we think it

more likely that the Plains Villagers who settled at the Harrell

site shared many customs with other Plains peoples because

they were themselves Plains Indians, people who moved into

the area from the north.

The ethnic identity of the Plains Villagers

who lived at the Harrell site is unknown. In the archeological

literature, the possibility that the people who lived at the

site might be ancestors of the historic Wichita is often mentioned.

While this idea was discounted by Krieger, Jack Hughes argued

in his 1968 dissertation, Prehistory of Caddoan-Speaking

Tribes, that the Harrell site represents an early Kichai

(Kitsai) village. The Kichai spoke a minor Caddo language,

but were one of at least six named groups who became consolidated

during the historic era into the Wichita tribe (the others

were the Taovaya, Tawakoni, Iscani, Wichita proper, and Waco).

Given the shared similarities among these groups, the great

difficulty in tracing the movement of peoples even in historic

times, and the radical changes the Wichita groups experienced

as the result of the introduction of European guns, horses,

and diseases, we will probably never know for sure.

While we may never know the precise ethnic

identity of the Plains Villagers at the Harrell site, we can

guess that they spoke a Caddoan language (as did many groups

living on and near the southern Plains including the various

Caddo and Wichita groups). Based on linguistic evidence we

know that Caddoan languages were spoken by many groups over

a very large area stretching from east Texas and southeastern

Arkansas across northern Texas and much of Oklahoma and north

into Kansas and the central Plains. Broadly these people all

shared a common cultural heritage, in much the same way that

most Europeans do. Just as in Europe, the peoples who lived

in the southern and central Plains moved repeatedly over the

centuries, split apart, fought with one another, intermarried,

and otherwise transformed their cultures and their identities

in complex ways that defy simple classification. In other

words, the PlainsVillagers who lived at the Harrell site were

part of a prehistoric era that dates hundreds of years before

the earliest historic accounts of named ethnic groups. We

cannot give them a familiar name, which is one of the reasons

why Alex Krieger coined the term Henrietta focus.

There is little or no indication that the Harrell

site continued to be occupied after A.D. 1500. A single blue

glass trade bead was found, but it is of a late style dating

no earlier than the Kickapoo village (1850s). Other late historic

Indian remains may well have been mixed in with the burned

remains of the Harrell family's farmhouse. The WPA archeologists

did not recognize any obvious Indian artifacts and discarded

almost all of the historic debris they found.

We close by repeating Jack Hughes' shrewd observation:

"Reconstructing the history of the part of the Brazos

on which the Harrell is located is like trying to visualize

a motion picture on the basis of a few still photographs."

Archeologists may never know enough to replay the movie version

of the long and varied human history of the upper Brazos.

But we can and will learn more as research moves forward into

the 21st century. The artifacts and records from Harrell site

collections from the 1937-1938 WPA excavations remain a critical

and largely untapped source of information awaiting further

study.

|

As a graduate student at the University

of Texas at Austin, Jack Hughes began the analysis of

the complex Harrell site evidence which still continues

today. He is shown here with a reconstructed vessel

from another site.

|

Antler tine tools such as these were

used over time for making chipped stone tools and other

purposes.

|

The deep Clear Fork of the Brazos

River. Situated at the river's juncture with the Salt

Fork, the Harrell site has been effected by both undercutting

and flooding.

|

Tools, arrow points, and performs

from the Harrell site, as illustrated in Krieger's Culture

Complexes and Chronology in Northern Texas, 1946.

|

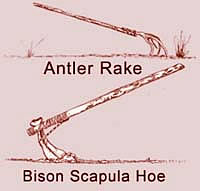

As they took up farming, Plains groups

used tools made from bone and antler, such as this bison

scapula hoe and antler rake. (Figure redrawn by Lynet

Dagel from Gilbert L. Wilson, Agriculture of the Hidatsa

Indians, copyright 1983 by the South Dakota State Historical

Society. Used with permission.)

|

Krieger's stratigraphic profiles

of Excavation 3, showing the layer of dark midden earth

(II) and underlying reddish sandy clay (I). Because

earlier artifacts such as dart points were found with

later arrow points and pottery, Krieger incorrectly

concluded that the older types continued to be used

by later peoples. Profile from Krieger, 1946.

|

Map of hearths in the Excavation

3 area. As shown, their depths ranged from 1 to 5 feet

below surface. Map from Hughes, 1942.

|

A rough field sketch of two unusual

features of fire-baked clay. Fox noted twig and grass

impressions in the lower feature that he thought might

represent wattle work. What the oval depressions within

the layer of cemented ash in the upper feature represent

is unknown.

|

A Henrietta focus house pattern recorded

at the Fish Creek site in Cooke County, Texas. Post

holes appear to form an oval shape and surround interior

hearths and cache pits. Map adapted from Lorraine, 1969.

|

An archeologist examines a feature

on the southwest edge of the "Great Midden."

Photo from TARL Archives.

|

|