|

In looking at the artifacts from Excavation 3, we

see traces of a people who farmed, hunted bison and

other game in the prairies and woods, and fished and

gathered mussel in the rivers. They also fashioned pottery

vessels of clay tempered with crushed mussel shell and

made both practical and decorative objects of bone,

shell, and chipped stone.

|

Excavators found this deer antler

and bone among camp refuse, underneath a hearth. They

are examples of the many resources suitable for food,

tools, or both used by the prehistoric dwellers at the

site.

|

A spatulate tool with beveled edges

was made from a bison or deer rib.

|

Late dart point types found at the

site. The smaller Darl points are considered "transitional"

types, among the last of the dart points still used

as the bow and arrow weaponry system came into use.

|

Side-notched points such as these

were found in quantity at the site. Those with side

notches only are called Washita points; those with side

and basal notches are known as Harrell points, for which

the site was named. Harrell points are found widely

in Late Prehistoric sites across Texas as well as across

the Plains and as far north as Canada.

|

The variety of dart points found

at the Harrell site, shown in this drawing from Krieger

1946, suggests the site was used by prehistoric peoples

for several thousand years before the Plains Village

groups came to the spot.

|

Chipped stone scrapers and cutting

tools of various shapes and sizes likely served a variety

of uses in butchering and other camp tasks. The brightly

colored pinkish-red specimen is made of Alibates "flint,"

a banded dolomite occurring chiefly in the Texas Panhandle

area to the northwest. (For more on how these stones

were procured, see the Alibates

Flint Quarries section.) |

The edge of this mussel

shell has been cut, or serrated, perhaps for use as a scraping or cutting

tool. |

Bones of various species of animal

were sharpened to use as awls, tools to sew or punch

holes in hides for clothing, containers, or other materials.

Fiber mats were woven with the aid of pointed tools

such as these.

|

Among the large selection of perforators

or drills found at the site, about 40 were simply made

on flakes, unshaped except for the drill shaft.

|

| |

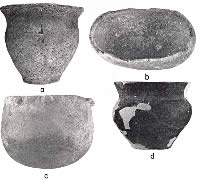

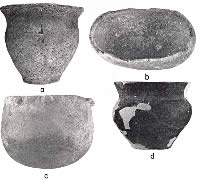

Although termed Nocona Plain, a small

number of sherds were decorated with simple exterior

designs including rounded nodes, impressions of textile

or paddle, incised lines, and parallel lines of fingernail

marks.

|

Once reconstructed, sherds of Nocona

Plain pottery from the Harrell site might resemble these

vessels found in graves in east-central Oklahoma and

northeast Texas, according to Krieger. He suggested

these vessels may have been trade ware brought into

areas where this type of pottery was not locally manufactured.

Vessels a and b were found in LeFlore County, Oklahoma.

Vessel c was from a site in Fannin County, Texas, and

Vessel d from a Titus focus burial in Titus County,

Texas. (Photo from Krieger 1946).

|

Unlike other types of pottery at

the site, these distinctive reddish sherds were not

tempered with shell and they apparently had been hand

molded rather than coiled. Based on the distinctive

red coloring on the interior, they may have once been

cups which held pigment for painting.

|

Exteriors of the reddish "paint

cup" sherds were roughened with incised lines or

other texturing, perhaps to make the vessels less slippery

to hold.

|

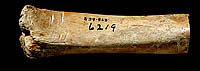

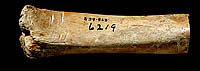

Cut marks and a clean-cut end indicate

this bone has been butchered by humans.

|

Marked with a series of carefully

incised parallel notches, these hollow bones had a purpose

we can only guess at today. Although often called "tally

bones" and considered counting devices, they are

more likely rasps used as musical or ceremonial instruments.

|

An array of beads and ornaments made

of different materials, including polished bird bones

( right), an Olivella shell bead (bottom right), mussel

shell disc beads (top, center), and disc beads of fossil

crinoid stems (bottom, center). The perforated object

at top left is made of baked clay and is probably a

spindle whorl, suggesting that cotton or other kinds

of plant fibers were woven at the site.

|

A single strap-handled sherd was

all that was found of a Brownware pottery vessel likely

made in southeastern New Mexico during the late 1400s.

|

A dart point with a complex past,

this specimen was made of banded agatized dolomite,

or Alibates flint, which outcrops along the Canadian

Breaks of the Texas Panhandle some 300 miles northwest

of the site. The style of the point resembles types

more common in East Texas and Louisiana, perhaps as

early as 3000 years ago.

|

|

Over time, hundreds of stone tools, weapons,

pottery sherds, bone implements, food remains, and other items

were left behind by the various occupants of the Harrell site.

What can these bits of household debris tell us about the

people who lived along the Brazos River and what their lives

were like?

A first consideration for researchers analyzing

site remains is identifying where each item came from in the

site deposits in order to understand its placement in time.

Like many prehistoric sites, the Harrell site does not represent

a single episode of occupation by one group of people. Rather,

the types of artifacts, ranging from roughly 5000-year-old

spear points to 600-year-old arrow points, tell us that the

site had a rather long history, as is discussed in the section,

Harrell Site Reconsidered. The challenge for archeologists

studying the Harrell site is to determine which artifacts

date to the same time period and represent the same period

of site occupation. Because of the nature of the site itself

as well as the way it was excavated and documented, the task

of sorting things out into meaningful groupings is no easier

today than it was 70 years ago when archeology student Jack

Hughes began looking at the collections.

Here we will simplify the matter and concentrate

mainly on the materials that date from the Plains Villager

period at the Harrell site, roughly A.D. 1200-1500. This period

accounts for the bulk of the artifacts from the site and it

is this period for which the site is best known. Artifacts

known or suspected to date to earlier periods are identified

as such.

Farming Tools

Farming implements were made from a variety

of materials close at hand, including bone and antler from

both deer and bison and shell from freshwater mussel. Plains

Villager farmers commonly used hoes made of bison scapulae

(shoulder blades) that were trimmed and cut to make a flat

triangular blade, which was attached to a wooded handle. Fourteen

fragments of bison scapula hoes were found at the Harrell

site (representing at least four or five whole tools). Another

hoe was fashioned from a section cut from a bison skull near

the horn core. Bone hoes may not have been common because

of the ready availability of large thick mussel shells, some

33 of which were found that show signs of heavy wear and battering

along their edges. These large shells may have been used as

digging tools or hoes to cultivate corn and perhaps other

crops (corn cobs were the only domesticated plant remains

recognized at the site).

A large mussel shell with heavy edge wear

and polish likely was used as a tool. Krieger suspected that

prehistoric farmers were using them as hoes, and that the

holes found in many shells were where a stick was inserted

to form a handle. Click image to enlarge. Click here for microscopic

views of edge.

Hunting, Fishing, and Butchering

Among a variety of implements, the tool kit

of prehistoric hunters included chipped stone or bone points

to tip weapons, gear for fishing and trapping, and the knives

and other tools to process their kill.

"Turtle-backed" scrapers, so-called

for their rounded hump-back appearance, likely were hafted

in bone or wooden handles for use in butchering and preparing

animal hides. Also called snubnosed end scrapers, the scrapers

were chipped unifacially (on one side) on a stone flake and

beveled on the wide end. They are commonly found in Late Prehistoric

sites, particularly those of bison hunting people.

Plains Indians often hafted small, plano-convex,

chipped stone end scrapers into antler tine handles for use

in hide working. These specimens, from Rice County, Kansas,

show various views of scraper blades in sockets. Drawings

by Marcia Bakry (a) and G. R. Lewis (b-d), from Wedel, 1970.

Used with permission of Plains Anthropologist.

Most of the 81 dart or spear points found at

the Harrell site date to the Archaic period before the bow

and arrow was in use. Dart points were affixed to wooden darts

or small spears thrown with the use of an atlatl or spear

thrower. Their presence tells us that the site was used by

hunters at least as early as 5000 years ago, the approximate

age of the beveled-stem Nolan points. Later Archaic styles

found at the site include the broad-bladed Castroville, Marcos,

and Marshall types, all dating to the Late Archaic about 2000-3000

years ago, as well as smaller and later types such as Darl,

Ensor, and Fairland points, all dating to the very end of

the Archaic, about 1200-2000 years ago. Some of the smaller

dart points may have still been in use when the bow and arrow

was introduced.

Arrow points were much more numerous; over 550

of them were recovered from the Harrell site. Most of these

are triangular points that have side and/or basal notches

including the Harrell style, named after the site, and the

Washita point. Scallorn points, the kind found with the burials,

are much less common; only about 25 were found. There are

also various other stemmed points including Bonham and a few

Perdiz as well as unstemmed and unnotched triangular points

and preforms.

Long bifaces or knives, some beveled on

edges, were likely used in cutting meat, plant foods, or in

other tasks.

A typical tool found at Plains Village sites

and other Late Prehistoric sites with evidence for bison hunting

is the beveled knife. These stone tools were probably favored

for their durability and longevity. Beginning as long oval-shaped

thin bifaces, their edges were resharpened repeatedly through

"microflaking" or edge-beveling and reused in successive

butchering tasks. As a knife was reused and resharpened over

its "lifetime," it became progressively narrower

with steeply angled, or beveled edges. Particularly distinctive

are narrow diamond-shaped or 4-beveled knives. While beveled

knives were used over a wide region, the diamond beveled knives

are particularly common in Plains Village sites. Several of

those from the Harrell site are made from Alibates flint (banded

dolomite, technically) that outcrops near Amarillo, some 250

miles to the northeast of the Harrell site.

Tools to Make Tools

Prehistoric toolmakers used a variety of tools

and resources in their work. Knappers would have employed

bone and antler batons and hammers as well as small rounded

hammerstones in the first stages of removing flakes from larger

pieces of chert (flint) or other stone suitable for flaking.

Flakes removed in this fashion were then chipped further and

finished using more intricate tools, such as antler tines.

Grooved sandstone tablets may also have been used in tool

making and maintenance, for dulling surfaces or for straightening

heated wooden shafts for arrows. For other tasks, chipped

stone burins or gravers may have been used both for cutting

and grooving bones and for ornamental incising.

These flintknapping tools made of antler

and bone were used to make stone tools. The larger specimens

likely served as "billets" or soft hammers for striking

flakes off pieces of stone, such as flint or chert, whereas

the three pointed antler tools on right are flaking tools

used to remove small flakes from nearly completed chipped

stone tools.

Food Processing, Cooking, and Storage

Amid the quantities of burned rock and other

hearth debris were quantities of grinding stone fragments

and pottery sherds—all that remained of the food processors,

cooking pots, and "Tupperware" of prehistoric times.

Milling and grinding implements, such as manos and metates,

were important processing tools for farming peoples who grew

corn. It is likely that—along with corn kernels—grass

seeds, mesquite beans, and nuts also were ground into flour

for making bread.

Of the handheld manos, some were made of hard

sandstone, others of quartzite or a hard, sandy limestone.

Most of the nearly 160 manos had been pecked or worked into

an oval shape, and showed signs of heavy wear. Two manos with

traces of red pigment may have been used for grinding hematite

or ocher for paint. The grinding slabs, often known as metates,

chiefly were made of hard sandstone; only 10 whole ones were

found among the 81 metate specimens. Grinding slab fragments

were often reused as cooking stones, or griddles; many of

these were found among the hearth stones.

Although a great deal of cooking involved use

of small hearths, ovens, and flat stone griddles, simple clay

pots were used for cooking stew-like meals and also for hauling

and storing water. To make the vessels, potters used crushed

mussel shell as a tempering agent and formed long coils of

clay into globular jars and deep bowls. The globular jars,

which had rounded bases, likely were cooking vessels.

Among the roughly 600 potsherds recovered at

the site, none could be refitted into whole vessels. Based

on similarities and differences, at least 25-30 separate vessels

are represented, according to a recent reexamination of the

collection by archeologist Michael Brack. Judging from the

sherds, most of the vessels were round-bottomed jars with

restricted necks, many of which flared out at the rims. The

openings of these jars were small—averaging 6 inches

(15 cm). A few bowls (at least 4) are also in the collection.

The vast majority of the site's potsherds (98%) are shell-tempered

plainwares, a few with simple decorations. Among the decorated

pieces, most had rows of appliquéd nodes; others had

vertical fingernail marks, incised diagonal lines, and stamped

impressions on the vessel body.

Krieger defined this type of pottery—shell-tempered,

coiled, globular-shaped, plain to only minimally decorated—from

the north central Texas area as Nocona Plain on the basis

of the Harrell site collection. The pottery was one of the

main "traits" or characteristics of the Henrietta

focus. Freshly crushed mussel shell was added as temper in

almost all the pottery from the site. Brack's study of shell-tempered

pottery from north Texas and Oklahoma found that the Harrell

site's pottery is the most technologically varied of any assemblage,

but closely resembles pottery found at sites along the Red

River and the Washita and Canadian River drainages in southern

and western Oklahoma. The variety of pottery and relatively

large number of vessels suggests that much of the pottery

found at Harrell was locally made.

A handful of very interesting and peculiar thick

pottery sherds up to an inch thick were unlike the other shell-tempered

pieces at the site. These appear to be fragments of small

"paint pots"-tall, narrow cylinders with 2-to 3-inch

(5-7 cm) openings. Two sherds have textured or roughened exteriors;

one with diagonal lines and the other with irregular but closely

spaced fingernail punctures or textile impressions, perhaps

to provide a better hand hold on the vessels. Interiors are

bright red, possibly from holding paint made of ochre. Similar

pottery has been found at other post A.D. 1200 sites in upper

Brazos and Red River locations as well as southern Oklahoma.

Food Remains

Based on charred and fragmentary remains left

behind in the cooking pits and midden rubble, the people of

the north-central Brazos ate a varied diet including buffalo,

deer, birds (turkey and small birds), turtle, freshwater drum

and other fish, and a quantity of freshwater mussels. Meat

would have been dried for use as jerky or pemmican, and bones

boiled or "greased," to extract fat. The later dwellers

also grew corn, as attested to by the fragments of charred

corn cobs preserved at the site, and collected pecans and

wild plums. Although few other food remains were recovered,

this is mainly because the archeologists did not realize the

importance of collecting charcoal and soil samples from hearths

and of using fine screening techniques to recover the bones

of small creatures. Based on what is known from other sites

in the region, we can guess that they also hunted a variety

of small mammals, collected the beans and acorns of the abundant

mesquite and oak trees in the area, and gathered a variety

of other plants, grasses, and seeds. Cactus, abundant today

in the area, may have been exploited for a variety of uses

as well.

In addition to the "tropical" domesticates"

such as corn, they probably raised other crops such as beans

and squash. Drass's study of earlier Washita River sites suggests

that domestication of plants on the southern Plains may have

started much earlier, with eastern Woodland domesticates such

as sun flower, marsh elder, and chenopodium.

Art, Ceremony, and Trade

An intricately incised bird bone with cross

hatched designs may have been used as an ornament or in a

special ritual.

Among the quantities of tools, debris, and more

mundane objects of daily life were a small number of items

bespeaking a desire to bring beauty and ceremony into the

lives of the people living along the Brazos. There were also

objects that indicated contact with groups in regions far

afield. Based on the array of "jewelry" found at

the site, at least some members of the group wore body ornaments,

including beads made of bone, fossil crinoids, and Olivella

shell, the latter from the Gulf of California over 700 miles

to the southwest. Cut and perforated mussel shells were probably

worn as pendants. Certain other mussel shell sections appeared

to be pendants or tools in the making—unfinished "blanks"

or oval discs cut from flat sections of larger shells.

Certain items may have been used in ceremonies

including elbow pipes for smoking native tobacco, tubes or

beads of bird bone, and rasps. The smoking pipes were made

of hard, fine-grained sandstone, and several were decorated

with lines incised around the pipe bowl rim, or with nicks

cut at intervals around the rim. This latter specimen also

has a hole drilled from the outside near the junction of stem

and bowl; archeologist Jack Hughes likened this specimen to

modern "carburetor" pipes. One interesting specimen

clearly saw much use, as indicated by a highly blackened bowl

interior.

Several distinctive sherds of pottery found

at the site were almost certainly brought or traded in from

other areas: one of southeastern New Mexico Brownware, and

one engraved sherd from the East Texas Caddo area.

That there was interaction or trade with people

from areas far afield is suggested in several items left at

the site including tools made from Alibates flint from the

Texas Panhandle, a biface made of black obsidian from the

Rocky Mountains to the west or northwest, Olivella shell from

the Gulf of California, and sherds of pottery unlike that

made at the site. One orange-colored polished sherd with an

incised design appears to be Poynor Engraved, a pottery type

made by Late Prehistoric groups along the upper Neches in

the East Texas Caddo area. Another is a Brownware sherd from

southeastern New Mexico. These probably represent trade wares

and suggest that the Harrell site was part of a larger trade

network. Both Southwestern and Caddo peoples were known to

be prodigious traders at various times in their history.

|

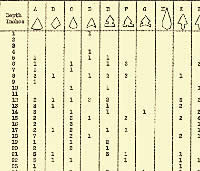

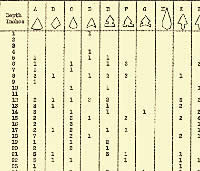

An initial attempt at analyzing artifact

distribution, George Fox's inventory of what he called "microliths," or small chipped stone tools

such as arrow points, was based on the depth at which

they were uncovered. Document from TARL Archives.

Click images to enlarge

|

Shaped hematite tools such as these

may once have been hafted on a wooden handle or used

as fist axes. The edges of these specimens have been

polished through use.

|

Tiny arrow points, known to collectors

as "bird points" for their small size, were

capable of felling large animals such as bison as well

as much smaller prey.

|

Chipped stone gouges or end scrapers with beveled

bit ends would have been effective tools for woodworking

or hide scraping.

|

Hoes made of bone. Prehistoric Plains

farmers used bone-tipped hoes and other simple digging

tools to cultivate corn and probably other crops as

well.

|

Dart points from earlier times at

the campsite: corner notched, wide-bladed Castroville,

Marcos and Marshall types dating to the Late Archaic

period roughly 2000-2500 years ago.

|

Edge beveling of bifacial knives

is well illustrated in this drawing. Specimen b is a

"two-bevel form" and c-d are "four-bevel

forms." Item i is a biface in an early stage of

use, suggesting what the original size and shape might

have been before successive edge use-wear and resharpening

processes. While beveling reduces the width and causes

edges to become increasingly beveled or angled, the

tool's thickness is maintained and durability enhanced.

Item g is a simple cutting tool made on a flake. (Size

½; drawing from Krieger 1946, Figure 7.)

|

Prehistoric fishermen might have

tied thin sinew or plant fibers to bone fishhooks, such

as this unfinished specimen from the Harrell site, for

fishing in the nearby Clear Fork River.

|

Grooved sandstones such as these

may have served as abraders, or whetstones, to variously

sharpen, dull, or smooth the edges of stone tools, or

for straightening or polishing wooden arrow shafts or

bone tools during manufacturing.

|

Filled with pitch or asphaltum, early

forms of glue, this mussel shell made a handy container.

The pitch may have been used to secure chipped stone

tools and points into the hafts of handles and shafts.

|

| |

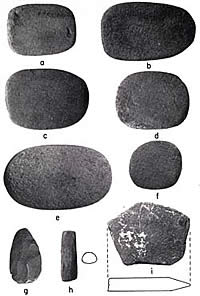

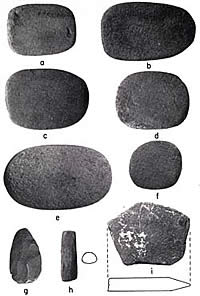

Manos and other stone implements

used for food processing at the Harrell site. Pecked,

or shaped, grinding tools such as manos ( a-e) were

handheld and likely moved in a back and forth motion

on a metate or coarse grinding slab. The small, unshaped

sandstone mano (f) was used in a rotary motion. Item

g is a chipped hematite blade, h, a polished sandstone

cylinder-shaped object, and i, a fragment of a beveled-edge

sandstone tablet. (Krieger 1947, Figure 12).

|

Crushed shell temper shows up as

white flecks within pottery sherds of Nocona Plain.

The variation in color is due largely to differences

in firing this simple pottery.

|

Rim profiles of shell-tempered Nocona

Plain pottery vessels from the Harrell site. Jars and

bowls with globular bodies and rounded bases were the

primary vessel shapes. Drawing from Michael Brack, 1999.

|

Mussel shells with mysterious holes.

Mussels gathered from nearby rivers were a useful resource

for the peoples of the area, as evidenced by the tens

of thousands of shells recovered at the site. In addition

to eating the fleshy mollusks, the Harrell site people

also used the shells as tools and containers, cut them

into beads and pendants, and crushed them for temper

in making pottery. The purpose of the holes, found on

many of shells, is unknown.

|

Now in fragments, these sandstone

pipes may have been smoked in special ceremonies. The

specimen on left has been decorated with incised lines

and small nicks around the rim; the elbow pipe on far

right shows the right angle juncture for which it is

named.

|

To make disc beads and pendants from

mussel shell, workers would cut sections of the shells

near the hinge, shape them into circular discs or other

forms, and perforate them to be strung on a cord.

|

Brightly colored hematite stones,

or ocher, may have been ground for pigment used for

body paint. Several manos, or grinding stones, from

the site bore traces of red pigment as did fragments

of pottery cups.

|

|